A Proposed New Military Justice Regime for the Australian Defence Force During Peacetime and in Time of War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Military and Veterans' Health

Volume 16 Number 1 October 2007 Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health Deployment Health Surveillance Australian Defence Force Personnel Rehabilitation Blast Lung Injury and Lung Assist Devices Shell Shock The Journal of the Australian Military Medicine Association Every emergency is unique System solutions for Emergency, Transport and Disaster Medicine Different types of emergencies demand adaptable tools and support. We focus on providing innovative products developed with the user in mind. The result is a range of products that are tough, perfectly coordinated with each other and adaptable for every rescue operation. Weinmann (Australia) Pty. Ltd. – Melbourne T: +61-(0)3-95 43 91 97 E: [email protected] www.weinmann.de Weinmann (New Zealand) Ltd. – New Plymouth T: +64-(0)6-7 59 22 10 E: [email protected] www.weinmann.de Emergency_A4_4c_EN.indd 1 06.08.2007 9:29:06 Uhr Table of contents Editorial Inside this edition . 3 President’s message . 4 Editor’s message . 5 Commentary Initiating an Australian Deployment Health Surveillance Program . 6 Myers – The dawn of a new era . 8 Original Articles The Australian Defence Deployment Health Surveillance Program – InterFET Pilot Project . 9 Review Articles Rehabilitation of injured or ill ADF Members . 14 What is the effectiveness of lung assist devices in blast injury: A literature review . .17 Short Communications Unusual Poisons: Socrates’ Curse . 25 Reprinted Articles A contribution to the study of shell shock . 27 Every emergency is unique Operation Sumatra Assist Two . 32 System solutions for Emergency, Transport and Disaster Medicine Biography Surgeon Rear Admiral Lionel Lockwood . 35 Different types of emergencies demand adaptable tools and support. -

Stoker DOUGLAS HUBERT FLETCHER B5527, HMAS Moreton, Royal Australian Navy Who Died Age 29 on 6 January 1947

In memory of Stoker DOUGLAS HUBERT FLETCHER B5527, HMAS Moreton, Royal Australian Navy who died age 29 on 6 January 1947 Son of Hubert Sidney Fletcher and Olive Louise Marguerite Fletcher; of Hawthorne, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia Remembered with honour MOUNT THOMPSON CREMATORIUM STOKER DOUGLAS HUBERT FLETCHER ROYAL AUSTRALIAN NAVY SERVICE NUMBER: B5527 Stoker Douglas Hubert Fletcher, the son of Hubert Sidney Fletcher and Olive Louise Marguerite Fletcher (nee Simmons) was born at Brisbane in Queensland on 19th March 1927. He was educated at the Toowoomba Grammar School. After leaving school he entered employment as a Clerk. At the age of 18 years and 2 months he was mobilized into the Royal Australian Navy Reserve on 31st May 1945. His physical description was that he was 5 feet 7 inches in height and had a fair complexion, green eyes, and light brown hair. He stated that he was of the Methodist religion. He gave his next of kin as his father, Mr Hubert Sidney Fletcher, residing at “Loombra”, Birkain Street, Hawthorne, Brisbane. He was allotted the service number of B5527. He joined H.M.A.S. Cerberus for his initial naval training on 5th June 1945. Stoker Douglas Fletcher joined the shore base H.M.A.S. Penguin at Balmoral, Middle Head, Sydney on 28th November 1945 to prepare for a sea posting. He joined the crew of HMAS Lachlan on 3rd December 1945. He joined the crew of HMAS Townsville, an Australian minesweeper on 23rd December 1945 an\d he served on this vessel until 26th February 1946. He joined the shore base HMAS Lonsdale 27th February 1946. -

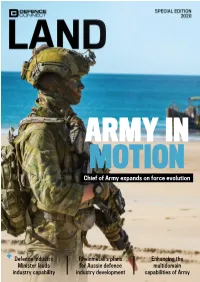

Chief of Army Expands on Force Evolution

ARMY IN MOTION Chief of Army expands on force evolution + Defence Industry Rheinmetall’s plans Enhancing the Minister lauds for Aussie defence multidomain industry capability industry development capabilities of Army Welcome EDITOR’S LETTER Army has always been the nation’s first responder. Recognising this, government has moved to modernise the force and keep it at the cutting-edge of capability Shifting gears, Rheinmetall Defence Australia provides a detailed look into their extensive research and development programs across unmanned systems, and collaborative efforts to Steve Kuper develop critical local defence industry capability. Analyst and editor Local success story EPE Protection discusses Defence Connect its own R&D and local industry and workforce development efforts, building on its veteran- focused experience in the land domain. WHILE BOTH Navy and Air Force are Luminact discusses the importance of well progressed on their modernisation information supremacy and its role in and recapitalisation programs, driven by supporting interoperability. The company also platforms like the F-35 Joint Strike Fighters discusses how despite platform commonality, and Hobart Class destroyers, Army is at the interoperability can’t be guaranteed and needs beginning of this process. Following on from to be accounted for. the success of the Defence Connect Maritime HENSOLDT Australia chats about its growing & Undersea Warfare Special Edition, this footprint across the ADF, with expertise second edition focused on the Land Domain learned during the company’s relationship with will deep-dive into the programs, platforms, Navy and Air Force to build a diverse offering, capabilities and doctrines emerging that will enhancing Army’s survivability and lethality. -

Putting the 'War' Back Into Minor War Vessels: Utilising the Arafura Class

Tac Talks Issue: 18 | 2021 Putting the ‘War’ back into Minor War Vessels: utilising the Arafura Class to reinvigorate high intensity warfighting in the Patrol Force By LEUT Brett Willis Tac Talks © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print, and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice and imagery metadata) for your personal, non-commercial use, or use within your organisation. This material cannot be used to imply an endorsement from, or an association with, the Department of Defence. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Tac Talks Introduction It is a curious statistic of the First World War that more sailors and officers were killed in action on Minor War Vessels than on Major Fleet Units in all navies involved in the conflict. For a war synonymous with the Dreadnought arms race and the clash of Battleships at Jutland the gunboats of the Edwardian age proved to be the predominant weapon of naval warfare. These vessels, largely charged with constabulary duties pre-war, were quickly pressed into combat and played a critical role in a number of theatres rarely visited in the histories of WWI. I draw attention to this deliberately for the purpose of this article is to advocate for the exploitation of the current moment of change in the RAN Patrol Boat Group and configure it to better confront the very real possibility of a constabulary force being pressed into combat. This article will demonstrate that prior planning & training will create a lethal Patrol Group that poses a credible threat to all surface combatants by integrating guided weapons onto the Arafura Class. -

2020 Yearbook

-2020- CONTENTS 03. 12. Chair’s Message 2021 Scholarship & Mentoring Program | Tier 2 & Tier 3 04. 13. 2020 Inductees Vale 06. 14. 2020 Legend of Australian Sport Sport Australia Hall of Fame Legends 08. 15. The Don Award 2020 Sport Australia Hall of Fame Members 10. 16. 2021 Scholarship & Mentoring Program | Tier 1 Partner & Sponsors 04. 06. 08. 10. Picture credits: ASBK, Delly Carr/Swimming Australia, European Judo Union, FIBA, Getty Images, Golf Australia, Jon Hewson, Jordan Riddle Photography, Rugby Australia, OIS, OWIA Hocking, Rowing Australia, Sean Harlen, Sean McParland, SportsPics CHAIR’S MESSAGE 2020 has been a year like no other. of Australian Sport. Again, we pivoted and The bushfires and COVID-19 have been major delivered a virtual event. disrupters and I’m proud of the way our team has been able to adapt to new and challenging Our Scholarship & Mentoring Program has working conditions. expanded from five to 32 Scholarships. Six Tier 1 recipients have been aligned with a Most impressive was their ability to transition Member as their Mentor and I recognise these our Induction and Awards Program to prime inspirational partnerships. Ten Tier 2 recipients time, free-to-air television. The 2020 SAHOF and 16 Tier 3 recipients make this program one Program aired nationally on 7mate reaching of the finest in the land. over 136,000 viewers. Although we could not celebrate in person, the Seven Network The Melbourne Cricket Club is to be assembled a treasure trove of Australian congratulated on the award-winning Australian sporting greatness. Sports Museum. Our new SAHOF exhibition is outstanding and I encourage all Members and There is no greater roll call of Australian sport Australian sports fans to make sure they visit stars than the Sport Australia Hall of Fame. -

The Australian Defence, Police and Emergency

THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE, POLICE AND EMERGENCY SERVICES LEADERSHIP SUMMIT 2015 ASSOCIATION MEMBER RATES Developing Today’s Managers LIMITED SEATS for Leadership Excellence AVAILABLE PREVIOUS SUMMIT SPEAKERS INCLUDE: David Melville APM David Irvine Lieutenant General Tony Negus APM Rear Admiral D.R. Air Marshal Ken D. Lay APM Warren J. Riley Former Commissioner, Former Director General David Morrison AO Former Commissioner Thomas AO, CSC, RAN Mark Binskin AO Former Chief Commissioner, Former Superintendent, QLD Ambulance Service of Security ASIO Chief of Army Australian Federal Police Former Deputy Former Vice Chief of the Victoria Police New Orleans Chief of Navy Defence Force (VCDF) Police Department The Australian Defence, Police and Emergency Services Leadership Summit 2015 will be held in Melbourne on Thursday 25th and Friday 26th June. In its sixth year, this HOST CITY significant national program drawing together the sectors most respected thought leaders with the aim to equip managers/leaders with the skills to adapt and respond ef- fectively, particularly in highly pressurised or extreme situ- PARK HYATT, MELBOURNE ations where effective leadership saves lives. 25TH & 26TH JUNE PRESENTING ORGANISATIONS FROM THE 2012, 2013 & 2014 SUMMITS INCLUDE: Australian Government Department of Defence THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE, POLICE AND EMERGENCY SERVICES LEADERSHIP SUMMIT 2015 OVERVIEW Including presentations from an esteemed line-up of high ranking officers and officials, as well as frontline and operational people managers, the Summit offers an unparalleled opportunity to observe effective individual and organisational leadership inside of Australia’s Defence, Police and Emergency Services. In addition to providing a platform to explore contemporary leadership practice, the Summit provides a unique opportunity for delegates to develop invaluable professional and personal networks. -

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible. -

October 2008 VOL

Registered by AUSTRALIA POST NO. PP607128/00001 THE October 2008 VOL. 31 No.5 The official journal of THE RETURNED & SErvICES LEAGUE OF AUstrALIA POSTAGE PAID SURFACE ListeningListening Branch Incorporated • PO Box 3023 Adelaide Tce, Perth 6832 • Established 1920 PostPostAUSTRALIA MAIL Vietnam Veterans Day 2008 The President, Mr Gaynor, said that he was “Well pleased that the Veteran Community and in particular Vietnam Veterans and Peacekeepers in their contribution to The Listening Post in remembering Vietnam Veterans Day. The Vietnam Vets are now coming forward and are making a welcome contribution to the administration of our Sub-Branches and other ex-service organisations (ESO’s)” Denis Connelly AATTV Advancing WA Week Memorial to Victory October Service at the 20-26 Memorial 2008 Page Page Page 7 17 22 Rick Hart - Proudly supporting your local RSL BELMONT 9373 4400 COUNTRY STORES BUNBURY SUPERSTORE 9722 6200 ALBANY - KITCHEN & LAUNDRY ONLY 9842 1855 CITY MEGASTORE 9227 4100 BROOME 9192 3399 CLAREMONT 9284 3699 BUNBURY SUPERSTORE 9722 6200 JOONDALUP SUPERSTORE 9301 4833 KATANNING 9821 1577 MANDURAH SUPERSTORE 9586 4700 COUNTRY CALLERS FREECALL 1800 654 599 MIDLAND SUPERSTORE 9267 9700 O’Connor SUPERSTORE 9337 7822 OSBORNE PARK SUPERSTORE 9445 5000 VIC PARK - PARK DISCOUNT SUPERSTORE 9470 4949 RSL Members receive special pricing. “We won’t be beaten on price. I put my name on it.”* Just show your membership card! 2 THE LIstENING Post October 2008 Celebrate WA Week with AHG. AHGVisitAHG ahg.com.au -- Australia’sAustralia’s and download Largest lots of MotoringWA savings! Group -- BUYBUY NOW!NOW! Offers from: Retravision, AHG Driving Centre, Perth Racing, Gloucester Park, WACA. -

Kemp - DHAAT 05 (28 May 2021)

Hulse and the Department of Defence re: Kemp - DHAAT 05 (28 May 2021) File Number(s) Re: Lieutenant Colonel George Hulse, OAM (Retd) on behalf of Colonel John Kemp AM (Retd) Applicant And: Department of Defence Respondent Tribunal Air Vice-Marshal John Quaife, AM (Retd) Presiding Member Major General Simone Wilkie, AO (Retd) Mr Graham Mowbray Hearing Date 24 February 2021 DECISION On 28 May 2021, having reviewed the decision by the Chief of Army of 26 February 2020 to not support the award of the Distinguished Service Cross to Colonel John Kemp AM (Retd) for his service in Vietnam, the Tribunal decided to recommend to the Minister for Defence that the decision by the Chief of Army be set aside and that Colonel Kemp be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his command and leadership of 1st Field Squadron Group, Vietnam, between 1 November 1967 and 12 November 1968. CATCHWORDS DEFENCE HONOUR – Distinguished Service Decorations – Distinguished Service Cross – eligibility criteria – 1st Field Squadron Group – Fire Support Base Coral - South Vietnam – MID nomination. LEGISLATION Defence Act 1903 – Part VIIIC - Sections 110T, 110V(1), 110VB(1), 110VB(6). Defence Regulation 2016, Section 35. Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No S25 – Distinguished Service Decorations Regulations – dated 4 February 1991. Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No S18 – Amendment of the Distinguished Service Decorations Regulations – dated 22 February 2012. REASONS FOR DECISION Introduction 1. The applicant, Lieutenant Colonel George Hulse OAM (Retd) seeks review of a decision by the Chief of Army, Lieutenant General Rick Burr AO DSC MVO, of 26 February 2020, to not recommend the award of the Distinguished Service Cross to Colonel John Howard Kemp for his service in Vietnam. -

CALL the HANDS NHSA DIGITAL NEWSLETTER Issue No.13 October 2017

CALL THE HANDS NHSA DIGITAL NEWSLETTER Issue No.13 October 2017 From the President The Naval Historical Society of Australia (NHSA) has grown over more than four decades from a small Garden Island, Sydney centric society in 1970 to an Australia wide organization with Chapters in Victoria, WA and the ACT and an international presence through the website and social media. Having recently established a FACEBOOK presence with a growing number of followers. Society volunteers have been busy in recent months enhancing the Society’s website. The new website will be launched in December 2017 at our AGM. At the same time, we plan to convert Call the Hands into digital newsletter format in lieu of this PDF format. This will provide advantage for readers and the Society. The most significant benefit of NHSA membership of the Society is receipt of our quarterly magazine, the Naval Historical Review which is add free, up to fifty pages in length and includes 8 to 10 previously unpublished stories on a variety of historical and contemporary subjects. Stories greater than two years old are made available to the community through our website. The membership form is available on the website. If more information is required on either membership or volunteering for the Society, please give us a call or e-mail us. Activities by our regular band of willing volunteers in the Boatshed, continue to be diverse, interesting and satisfying but we need new helpers as the range of IT and web based activities grows. Many of these can be done remotely. Other activities range from routine mail outs to guiding dockyard tours, responding to research queries, researching and writing stories. -

A Modern Day Anzac Summer Edition 2017

SUMMER EDITION 2017 REMEMBRANCE DAY 2016 ~ WREATH LAYING CEREMONY COUNCILOR DAVID BELCHER ~ WEST WARD ~ LMCC ANDREW MACRAE ~ PRESIDENT ~ WESTLAKE NASHO’S MEMBERS FEES DUE ~ Page 2 NOTICEA MODERN OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING DAY FEBRUARY ANZAC 2017 ~ Page 5 SR-71 ~ BLACKBIRD COMMUNICATION TO TOWER ~ Pages 8 to 10 SOME PHOTOGRAPHS OF OUR XMAS WELFARE CRUISE ~ Page11 THE BATTLE OF BRITAIN ~ 75 YEAR ON ~ Pages 12 to 13 THE TRUE REASON FOR THE RSL SALUTE ~ Page 27 INDIGE- NOUS SERVICE IN AUSTRALIA’S ARMED FORCES IN PEACE & WAR Pages 41 to 48 Official Newsletter of: Toronto RSL sub-Branch PO Box 437 Toronto 2283 [email protected] 02 4959 3699 NNEWCASTLEEWCASTLE ARMOURYARMOURYARMOURY LICENSED FIREARMS DEALER WANTED: EX-MILITARY AND SPORTING FIREARMS PHONE: 0448 032 559 E-MAIL: [email protected] PO BOX 3190 GLENDALE NSW 2285 www.newcastlearmoury.com.au THIS SPACE AVAILABLE FOR ADVERTISING In a time of need turn to someone you can trust. Ph. (02) 4973 1513 SO IF ANYONE OUT THERE WISHES TO PLACE A QUARTER PAGE ADVERTISEMENT IN- SIDE THE FRONT COVER WHICH IS DISTRIBUTED TO OUR MEMBERS AND Pre Arranged Funeral Plan in THE COMMUNITY AS A Association with WHOLE (APPROXIMATELY 1500 COPIES QUARTERLY) barbarakingfunerals.com.au From the president’s Hi all, Here we are another year gone and before you know it it will be Christmas 2017. We have had quite a busy year attending to the various as- pects of the sub-Branch which keeps the motor running. I have a great crew behind me in the running of this office from the Executive, Trustees, Pension and Welfare Offi- cers, the Committee and all others who do not have any specific duty but get in and help when it is needed. -

RAA Liaison Letter Spring 2015

The Royal Australian Artillery LIAISON LETTER Spring 2015 The Official Journal of the Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery Incorporating the Australian Gunner Magazine First Published in 1948 RAA Liaison Letter 2015 - Spring Edition CONTENTS Editor’s Comment 1 Letters to the Editor 5 Regimental 9 Professional Papers 21 Around the Regiment 59 RAA Rest 67 Capability 81 LIAISON Personnel & Training 93 Associations & Organisations 95 LETTER Spring Edition NEXT EDITION CONTRIBUTION DEADLINE Contributions for the Liaison Letter 2016 – Autumn 2015 Edition should be forwarded to the Editor by no later than Friday 12th February 2016. LIAISON LETTER ON-LINE Incorporating the The Liaison Letter is on the Regimental DRN web-site – Australian Gunner Magazine http://intranet.defence.gov.au/armyweb/Sites/RRAA/. Content managers are requested to add this to their links. Publication Information Front Cover: An Australian M777A2 from 8th/12th Regiment, RAA at Bradshaw Field Training Area, Northern Territory during Exercise Talisman Sabre 2015. The Talisman Sabre series of exercises is the principle Australian and US military training activity focused on the planning and conduct of mid-intensity ‘High End’ warfighting. Front Cover Theme by: Major D.T. (Terry) Brennan, Staff Officer to Head of Regiment Compiled and Edited by: Major D.T. (Terry) Brennan, Staff Officer to Head of Regiment Published by: Lieutenant Colonel Dave Edwards, Deputy Head of Regiment Desktop Publishing: Michelle Ray, Army Knowledge Group, Puckapunyal, Victoria 3662 Front Cover & Graphic Design: Felicity Smith, Army Knowledge Group, Puckapunyal, Victoria 3662 Printed by: Defence Publishing Service – Victoria Distribution: For issues relating to content or distribution contact the Editor on email: [email protected] or [email protected] Contributors are urged to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in their articles.