Sticking to Our Guns a Troubled Past Produces a Superb Weapon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC and Small Arms Survey by Eric G

SMALL ARMS: A REGIONAL TINDERBOX A REGIONAL ARMS: SMALL AND REPUBLIC AFRICAN THE CENTRAL Small Arms Survey By Eric G. Berman with Louisa N. Lombard Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland p +41 22 908 5777 f +41 22 732 2738 e [email protected] w www.smallarmssurvey.org THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND SMALL ARMS A REGIONAL TINDERBOX ‘ The Central African Republic and Small Arms is the most thorough and carefully researched G. Eric By Berman with Louisa N. Lombard report on the volume, origins, and distribution of small arms in any African state. But it goes beyond the focus on small arms. It also provides a much-needed backdrop to the complicated political convulsions that have transformed CAR into a regional tinderbox. There is no better source for anyone interested in putting the ongoing crisis in its proper context.’ —Dr René Lemarchand Emeritus Professor, University of Florida and author of The Dynamics of Violence in Central Africa ’The Central African Republic, surrounded by warring parties in Sudan, Chad, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, lies on the fault line between the international community’s commitment to disarmament and the tendency for African conflicts to draw in their neighbours. The Central African Republic and Small Arms unlocks the secrets of the breakdown of state capacity in a little-known but pivotal state in the heart of Africa. It also offers important new insight to options for policy-makers and concerned organizations to promote peace in complex situations.’ —Professor William Reno Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Political Science, Northwestern University Photo: A mutineer during the military unrest of May 1996. -

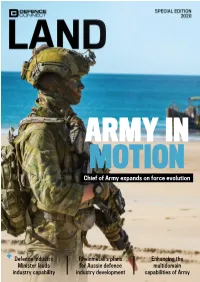

Chief of Army Expands on Force Evolution

ARMY IN MOTION Chief of Army expands on force evolution + Defence Industry Rheinmetall’s plans Enhancing the Minister lauds for Aussie defence multidomain industry capability industry development capabilities of Army Welcome EDITOR’S LETTER Army has always been the nation’s first responder. Recognising this, government has moved to modernise the force and keep it at the cutting-edge of capability Shifting gears, Rheinmetall Defence Australia provides a detailed look into their extensive research and development programs across unmanned systems, and collaborative efforts to Steve Kuper develop critical local defence industry capability. Analyst and editor Local success story EPE Protection discusses Defence Connect its own R&D and local industry and workforce development efforts, building on its veteran- focused experience in the land domain. WHILE BOTH Navy and Air Force are Luminact discusses the importance of well progressed on their modernisation information supremacy and its role in and recapitalisation programs, driven by supporting interoperability. The company also platforms like the F-35 Joint Strike Fighters discusses how despite platform commonality, and Hobart Class destroyers, Army is at the interoperability can’t be guaranteed and needs beginning of this process. Following on from to be accounted for. the success of the Defence Connect Maritime HENSOLDT Australia chats about its growing & Undersea Warfare Special Edition, this footprint across the ADF, with expertise second edition focused on the Land Domain learned during the company’s relationship with will deep-dive into the programs, platforms, Navy and Air Force to build a diverse offering, capabilities and doctrines emerging that will enhancing Army’s survivability and lethality. -

Suppressor Shootout: Desert Tactical SRS .338

GUN TEST Suppressor Shootout DESERT TACTICAL SRS .338 SILENT AND DEADLY, three long-range big bore rifle suppressors for today’s sniper! by LT. DAVE bAHDE Dipisim quisit essi tet, senisit il enissi. Onullao rtiscilis eugue doloborpero et, vero diam, conseniam zzriusc iduisi tat la consenibh eniam vulla feum et accum quisse feum duntLitDui tet volorer ip ex eniam ing JET he value of a suppressor on a sniper rifle. At a recent sniper school, driven by a .338 caliber sniper rifle sniper rifle has been subject about a third of the rifles were sup- contract currently in process with the to much debate. When sup- pressed. Years ago, I was the only Army, it is also driven by the need to Tpressors were heavy, short- one with a suppressed rifle and many reach out to longer distances. lived, cumbersome and affected asked, “Aren’t those illegal?” Sup- The .30 caliber cartridges accuracy, there was a basis for argu- pressors are now seen at training, op- even in magnum form are still SUREFIRE ment. However, modern suppressors erations and competitions. Well-made pretty much limited to 1000 help most shooters shoot more ac- suppressors are beginning to show yards or so. If you want to get Ed digna ad tet irilis curately. Improvements in materials up at police departments and military to 1500 yards and beyond you alissim qui endiamc om- technology and design have made units, especially SpecOps units. need more. There are certainly modiamet ad mincipisl ut them virtually maintenance-free, Although the .308 rifle is still bigger guns and cartridges that vullam, commole ssissit lighter and more compact. -

Illinois Current Through P.A

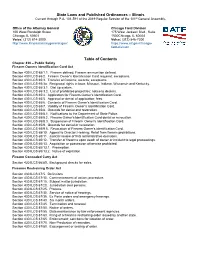

State Laws and Published Ordinances – Illinois Current through P.A. 101-591 of the 2019 Regular Session of the 101st General Assembly. Office of the Attorney General Chicago Field Division 100 West Randolph Street 175 West Jackson Blvd., Suite Chicago, IL 60601 1500Chicago, IL 60604 Voice: (312) 814-3000 Voice: (312) 846-7200 http://www.illinoisattorneygeneral.gov/ https://www.atf.gov/chicago- field-division Table of Contents Chapter 430 – Public Safety Firearm Owners Identification Card Act Section 430 ILCS 65/1.1. Firearm defined; Firearm ammunition defined. Section 430 ILCS 65/2. Firearm Owner's Identification Card required; exceptions. Section 430 ILCS 65/3. Transfer of firearms; records; exceptions. Section 430 ILCS 65/3a. Reciprocal rights in Iowa, Missouri, Indiana, Wisconsin and Kentucky. Section 430 ILCS 65/3.1. Dial up system. Section 430 ILCS 65/3.2. List of prohibited projectiles; notice to dealers. Section 430 ILCS 65/4. Application for Firearm Owner's Identification Card. Section 430 ILCS 65/5. Approval or denial of application; fees. Section 430 ILCS 65/6. Contents of Firearm Owner's Identification Card. Section 430 ILCS 65/7. Validity of Firearm Owner’s Identification Card. Section 430 ILCS 65/8. Grounds for denial and revocation. Section 430 ILCS 65/8.1. Notifications to the Department of State Police. Section 430 ILCS 65/8.2. Firearm Owner's Identification Card denial or revocation. Section 430 ILCS 65/8.3. Suspension of Firearm Owner's Identification Card. Section 430 ILCS 65/9. Grounds for denial or revocation. Section 430 ILCS 65/9.5. Revocation of Firearm Owner's Identification Card. -

2020 Yearbook

-2020- CONTENTS 03. 12. Chair’s Message 2021 Scholarship & Mentoring Program | Tier 2 & Tier 3 04. 13. 2020 Inductees Vale 06. 14. 2020 Legend of Australian Sport Sport Australia Hall of Fame Legends 08. 15. The Don Award 2020 Sport Australia Hall of Fame Members 10. 16. 2021 Scholarship & Mentoring Program | Tier 1 Partner & Sponsors 04. 06. 08. 10. Picture credits: ASBK, Delly Carr/Swimming Australia, European Judo Union, FIBA, Getty Images, Golf Australia, Jon Hewson, Jordan Riddle Photography, Rugby Australia, OIS, OWIA Hocking, Rowing Australia, Sean Harlen, Sean McParland, SportsPics CHAIR’S MESSAGE 2020 has been a year like no other. of Australian Sport. Again, we pivoted and The bushfires and COVID-19 have been major delivered a virtual event. disrupters and I’m proud of the way our team has been able to adapt to new and challenging Our Scholarship & Mentoring Program has working conditions. expanded from five to 32 Scholarships. Six Tier 1 recipients have been aligned with a Most impressive was their ability to transition Member as their Mentor and I recognise these our Induction and Awards Program to prime inspirational partnerships. Ten Tier 2 recipients time, free-to-air television. The 2020 SAHOF and 16 Tier 3 recipients make this program one Program aired nationally on 7mate reaching of the finest in the land. over 136,000 viewers. Although we could not celebrate in person, the Seven Network The Melbourne Cricket Club is to be assembled a treasure trove of Australian congratulated on the award-winning Australian sporting greatness. Sports Museum. Our new SAHOF exhibition is outstanding and I encourage all Members and There is no greater roll call of Australian sport Australian sports fans to make sure they visit stars than the Sport Australia Hall of Fame. -

Additional Estimates 2010-11

Dinner on the occasion of the First Meeting of the International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament Kirribilli House, Kirribilli, Sydney Sunday, 19 October 2008 Host Mr Francois Heisbourg The Honourable Kevin Rudd MP Commissioner (France) Prime Minister Chairman of the International Institute for Strategic Studies and Geneva Centre for Official Party Security Policy, Special Adviser at the The Honourable Gareth Evans AO QC Foundation pour la Recherche Strategique Co-Chair International Commission on Nuclear Non- General (Ret'd) Jehangir Karamat proliferation and Disarmament Commissioner (Pakistan) and President of the International Crisis Director, Spearhead Research Group Mrs Nilofar Karamat Ms Yoriko Kawaguchi General ((Ret'd) Klaus Naumann Co-Chair Commissioner (Germany) International Commission on Nuclear Non- Member of the International Advisory Board proliferation and Disarmament and member of the World Security Network Foundation of the House of Councillors and Chair of the Liberal Democratic Party Research Dr William Perry Commission on the Environment Commissioner (United States) Professor of Stanford University School of Mr Ali Alatas Engineering and Institute of International Commissioner (Indonesia) Studies Adviser and Special Envoy of the President of the Republic of Indonesia Ambassador Wang Yingfan Mrs Junisa Alatas Commissioner (China) Formerly China's Vice Foreign Minister Dr Alexei Arbatov (1995-2000), China's Ambassador and Commissioner (Russia) Permanent Representative to the United Scholar-in-residence -

2021 SB 370 by Senator Farmer 34-00616-21

Florida Senate - 2021 SB 370 By Senator Farmer 34-00616-21 2021370__ 1 A bill to be entitled 2 An act relating to assault weapons and large-capacity 3 magazines; creating s. 790.301, F.S.; defining terms; 4 prohibiting the sale or transfer of an assault weapon 5 or a large-capacity magazine; providing exceptions; 6 providing criminal penalties; prohibiting possession 7 of an assault weapon or a large-capacity magazine; 8 providing exceptions; providing criminal penalties; 9 requiring certificates of possession for assault 10 weapons or large-capacity magazines lawfully possessed 11 before a specified date; providing requirements for 12 the certificates; requiring the Department of Law 13 Enforcement to adopt rules; specifying the form of the 14 certificates; limiting sales or transfers of assault 15 weapons or large-capacity magazines documented by such 16 certificates; providing conditions for continued 17 possession of such weapons or large-capacity 18 magazines; providing requirements for an applicant who 19 fails to qualify for such a certificate; requiring 20 certificates of transfer for transfers of certain 21 assault weapons or large-capacity magazines; providing 22 requirements for certificates of transfer; requiring 23 the Department of Law Enforcement to maintain a file 24 of such certificates; providing for relinquishment of 25 assault weapons or large-capacity magazines; providing 26 requirements for transportation of assault weapons or 27 large-capacity magazines under certain circumstances; 28 providing criminal penalties; specifying circumstances 29 in which the manufacture or transportation of assault Page 1 of 18 CODING: Words stricken are deletions; words underlined are additions. Florida Senate - 2021 SB 370 34-00616-21 2021370__ 30 weapons or large-capacity magazines is not prohibited; 31 exempting permanently inoperable firearms from certain 32 provisions; amending s. -

MK 19, 40-Mm GRENADE MACHINE GUN, MOD 3

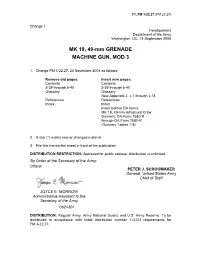

C1, FM 3-22.27 (FM 23.27) Change 1 Headquarters Department of the Army Washington, DC, 14 September 2006 MK 19, 40-mm GRENADE MACHINE GUN, MOD 3 1. Change FM 3-22.27, 28 November 2003 as follows: Remove old pages: Insert new pages: Contents Contents 5-39 through 5-40 5-39 through 5-40 Glossary Glossary New Appendix J: J-1 through J-18 References References Index Index Insert behind DA forms: MK 19, 40-mm Advanced Crew Gunnery; DA Form 7580-R through DA Form 7587-R (Gunnery Tables 1-8) 2. A star (*) marks new or changed material. 3. File this transmittal sheet in front of the publication. DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. By Order of the Secretary of the Army: Official: PETER J. SCHOOMAKER General, United States Army Chief of Staff JOYCE E. MORROW Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Army 0624301 DISTRIBUTION: Regular Army, Army National Guard, and U.S. Army Reserve: To be distributed in accordance with initial distribution number 114324 requirements for FM 3-22.27. This page intentionally left blank. C1, FM 3-22.27 (FM 23.27) FIELD MANUAL HEADQUARTERS NO. 3-22.27 DEPARTMENTS OF THE ARMY WASHINGTON, DC, 14 September 2006 MK 19, 40-mm GRENADE MACHINE GUN, MOD 3 CONTENTS Page PREFACE……………..................................................................................................... iv CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1. Applications .............................................................................1-1 1-2. Description ............................................................................... 1-1 1-3. Training Strategy ...................................................................... 1-8 CHAPTER 2. OPERATION AND FUNCTION 2-1. Cycle of Operation ................................................................... 2-1 2-2. Operating Precautions ..............................................................2-4 2-3. -

PREAMBLE Whereas the People of the State of Oregon Find That Gun Violence in Oregon and the United States, Resulting in Horrific

PREAMBLE Whereas the People of the State of Oregon find that gun violence in Oregon and the United States, resulting in horrific deaths and devastating injuries due to mass shootings and other homicides, is unacceptable at any level; and Whereas the firearms referred to as “semiautomatic assault firearms” are designed with features to allow rapid spray firing or the quick and efficient killing of humans, and the unregulated availability of semiautomatic assault firearms used in such mass shootings and other homicides in Oregon, and throughout the United States, poses a grave and immediate risk to the health, safety and well-being of the citizens of this State, and in particular our children; and Whereas firearms have evolved from muskets to semiautomatic assault firearms, including rifles, shotguns and pistols with enhanced features and with the ability to kill so many in such an increasingly short period of time, unleashing death and unspeakable pain in places that should be safe: our homes, schools, places of worship, shopping malls, communities; and Whereas a failure to resolve long unrest and inequitable treatment of individuals based on race, gender, religion and other distinguishing characteristics and failure to develop legislative tools to remove the ability of those with criminal intent or predisposition to commit violence from acquiring such instruments of carnage and never-ending sadness; It is therefore morally incumbent upon the citizens of Oregon to take immediate action, which we do by this initiative, to reduce the availability of these assault firearms, and thus reduce their ability to cause death and loss in places that should remain safe; Now, therefore, BE IT ENACTED BY THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF OREGON: SECTION 1. -

OTOLARYNGOLOGY/HEAD and NECK SURGERY COMBAT CASUALTY CARE in OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM and OPERATION ENDURING FREEDOM Section III

Weapons and Mechanism of Injury in Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom OTOLARYNGOLOGY/HEAD AND NECK SURGERY COMBAT CASUALTY CARE IN OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM AND OPERATION ENDURING FREEDOM Section III: Ballistics of Injury Critical Care Air Transport Team flight over the Atlantic Ocean (December 24, 2014). Photograph: Courtesy of Colonel Joseph A. Brennan. 85 Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Combat Casualty Care 86 Weapons and Mechanism of Injury in Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom Chapter 9 WEAPONS AND MECHANISM OF INJURY IN OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM AND OPERATION ENDURING FREEDOM DAVID K. HAYES, MD, FACS* INTRODUCTION EXPLOSIVE DEVICES Blast Injury Closed Head Injury SMALL ARMS WEAPONS Ballistics Internal Ballistics External Ballistics Terminal Ballistics Projectile Design Tissue Composition and Wounding WEAPONRY US Military Weapons Insurgent Weapons SUMMARY *Colonel, Medical Corps, US Army; Assistant Chief of Staff for Clinical Operations, Southern Regional Medical Command, 4070 Stanley Road, Fort Sam Houston, Texas 78234; formerly, Commander, 53rd Medical Detachment—Head and Neck, Balad, Iraq 87 Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Combat Casualty Care INTRODUCTION This chapter is divided into four sections. It first small arms weapons caused just 6,013 casualties dur- examines the shifts in weapons used in the combat ing the same time.2 Mortars and rocket-propelled zones of Iraq and Afghanistan, and compares them to grenades, although highly destructive, injured 5,458 mechanisms of wounding in prior conflicts, including and killed only 341 US soldiers during the same time comparing the lethality of gunshot wounds to explo- (Table 9-1). In a review of wounding patterns in Iraq sive devices. -

FN P90 Fact Sheet

SALW Guide Global distribution and visual identification FN P90 Fact sheet https://salw-guide.bicc.de FN P90 SALW Guide FN P90 A personal defense weapon (often abbreviated PDW) is a compact semi- automatic or fully-automatic firearm similar in most respects to a submachine gun, but firing an (often proprietary) armor-piercing round, giving a PDW better range, accuracy and armor-penetrating capability than submachine guns, which fire pistol-caliber cartridges.The P90 was designed to have a length no greater than a man's shoulder width, in order to be easily carried and maneuvered in tight spaces, such as the inside of an armored vehicle. To achieve this, the weapon's design utilizes the unconventional bullpup configuration, in which the action and magazine are located behind the trigger and alongside the shooter's face, so that there is no wasted space in the stock. The P90's dimensions are also minimized by its unique horizontally mounted feeding system, wherein the box magazine sits parallel to the barrel on top of the weapon's frame. Overall, the weapon has an extremely compact profile. Technical Specifications Category Submachine Guns Operating system Straight blowback, closed bolt Cartridge FN 5.7 x 28mm Length 500 mm Feeding n/a Global distribution map The data on global distribution and production is provided primarily by the BwVC1, but also from national and regional focal points on SALW control; data published by think tanks, international organizations and experts; and/or data provided by individual researchers on SALW. It is not exhaustive. If you would like to add to or amend the data, please use the website's feedback function. -

Asx Announcement

30 April 2013 ASX ANNOUNCEMENT Senetas Corporation announces appointment of Lieutenant General K.J Gillespie AC DSC CSM (retd) as a director. The chairman and board of Senetas Corporation Limited (ASX: Senetas) are pleased to announce the appointment of Lieutenant General Ken Gillespie to the board of the company, effective today. Ken Gillespie retired from the Army in June 2011 after a distinguished 43 year career. Ken had an outstanding career recognised by his appointment as Vice Chief of the Defence Force/Chief of Joint Operations and Chief of Army. He has had considerable overseas experience and developed a strong network of contacts in the defence, security and diplomatic fields. He demonstrated very high order strategic planning, engagement and implementation skills and excelled in many demanding high-command appointments. Ken was advanced to Companion in the Military Division of the Order of Australia in the Australia Day 2011 Honours List. He was previously advanced to Officer of the Order of Australia for his service as Commander Australian Contingent, Operation Slipper, having been a Member of the Order for his service as Commander ASTJIC. Significantly, he was also awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his command and leadership in East Timor in 2000/2001 and the Conspicuous Service Medal for his work in Namibia in 1989/90. As Lieutenant General, Ken was awarded the Legion of Merit (Commander) from the United States of America in 2009. In 2010, the Republic of Singapore awarded him the Meritorious Service Medal (Military - Pingat Jasa Gemilang). Ken also brings to the Senetas board substantial commercial experience.