The 'Item Number' in Indian Cinema: Deconstructing the Paradox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Soundtrack of Call for Fun Exudes Youthful Energy'

*BTM51017/ /05/K/1*/05/Y/1*/05/M/1*/05/C/1* THURSDAY 5 OCTOBER 2017 ENTERTAINMENT/VARIETY BOMBAY TIMES, THE TIMES OF INDIA 5 he season of love and ding an unforgettable experi- weddings is upon us. As ence. With performances at ‘The soundtrack of Call For T you plan your important over 350 weddings across 15 Adding a special events like the afterparty, countries for a culturally sangeet or mehendi for your diverse clientele, and with some wedding, make sure you don’t of the biggest global names as Fun exudes youthful energy’ miss out on planning the actual his clients, Ameya has become musical touch wedding ceremony rituals. Plan a renowned names in weddings Tejas Kudtarkar the music for your wedding ceremonies globally! Ameya pheras with The Signature renders sufi, ghazals and even Wedding Chants with The Bollywood songs to add a spe- to wedding Blissful Entertainer- Ameya cial touch to your celebrations. Dabli. His music is blissful, Call: +91 99203 27826. divine and yet entertaining E-mail: [email protected] enough to enthral your family YouTube: Ameya Dabli Ameya and friends to make your wed- www.ameyadabli.com ceremonies Dabli Lalit Pandit CONTINUED FROM PAGE 1 Salman (Khan) ko maine O O Jaane Jaana, mein dia- logues bulwaye thay and Shah Rukh Khan ko bhi Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani mein dialogues bulwaye thay. Rani and Saif contributed in the track Ladki Kyun Najane Kyun from Hum Tum. Earlier, Amitabh Bachchan had sung in some movies, but we restarted the trend in the newer generation. -

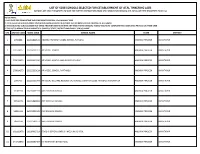

List of 6038 Schools Selected for Establishment of Atal Tinkering

LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. LAST DATE FOR COMPLETING THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS : 31st JANUARY 2020 2. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST OPEN A NEW BANK ACCOUNT IN A PUBLIC SECTOR BANK FOR THE PURPOSE OF ATL GRANT. 3. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST NOT SHARE THEIR INFORMATION WITH ANY THIRD PARTY/ VENDOR/ AGENT/ AND MUST COMPLETE THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS ON THEIR OWN. 4. THIS LIST IS ARRANGED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER OF STATE, DISTRICT AND FINALLY SCHOOL NAME. S.N. ATL UID CODE UDISE CODE SCHOOL NAME STATE DISTRICT 1 2760806 28222800515 ANDHRA PRADESH MODEL SCHOOL PUTLURU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 2 132314217 28224201013 AP MODEL SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 3 574614473 28223600320 AP MODEL SCHOOL AND JUNIOR COLLEGE ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 4 278814373 28223200124 AP MODEL SCHOOL RAPTHADU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 5 2995459 28222500704 AP SOCIAL WELFARE RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL JUNIOR COLLEGE FOR GIRLS KURUGUNTA ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 6 13701194 28220601919 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 7 15712075 28221890982 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 8 56051196 28222301035 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 9 385c1160 28221591153 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 10 102112978 28220902023 GOOD SHEPHERD ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 11 243715046 28220590484 K C NARAYANA E M SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. -

Seeking Offense: Censorship and the Constitution of Democratic Politics in India

SEEKING OFFENSE: CENSORSHIP AND THE CONSTITUTION OF DEMOCRATIC POLITICS IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Ameya Shivdas Balsekar August 2009 © 2009 Ameya Shivdas Balsekar SEEKING OFFENSE: CENSORSHIP AND THE CONSTITUTION OF DEMOCRATIC POLITICS IN INDIA Ameya Shivdas Balsekar, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 Commentators have frequently suggested that India is going through an “age of intolerance” as writers, artists, filmmakers, scholars and journalists among others have been targeted by institutions of the state as well as political parties and interest groups for hurting the sentiments of some section of Indian society. However, this age of intolerance has coincided with a period that has also been characterized by the “deepening” of Indian democracy, as previously subordinated groups have begun to participate more actively and substantively in democratic politics. This project is an attempt to understand the reasons for the persistence of illiberalism in Indian politics, particularly as manifest in censorship practices. It argues that one of the reasons why censorship has persisted in India is that having the “right to censor” has come be established in the Indian constitutional order’s negotiation of multiculturalism as a symbol of a cultural group’s substantive political empowerment. This feature of the Indian constitutional order has made the strategy of “seeking offense” readily available to India’s politicians, who understand it to be an efficacious way to discredit their competitors’ claims of group representativeness within the context of democratic identity politics. -

Use and Abuse of Female Body in Popular Hindi Films: a Semiotic Analysis of Item Songs

Use and Abuse of Female Body in Popular Hindi Films: A Semiotic analysis of Item Songs *Dr. G. K. Sahu Assistant Professor Dept. of Mass Communication Aligarh Muslim University Aligarh- 202002 & **Sana Abbas Research Scholar Dept. of Mass Communication Aligarh Muslim University Aligarh-202002 India Abstract The item songs have become an important element of Bollywood movies. Women are featured as a commodity, only to satisfy male urge and their bodies are featured in a way as if they are meant for male consumption. In an environment where a plethora of movies are releasing every year, putting a peppy item song in a movie, is a good trick to gain the attention of viewers . Brazen lyrics are used to enhance the popularity of these songs. Many established film makers in the industry are using this trick to gain huge financial returns. They are attracting and engaging audiences by using as well as abusing female body in their films. The paper makes an attempt to analyze the item songs by employing semiotic method to examine the use and abuse of female body in Hindi films. Key Words: Hindi Films, Item Songs, Female Body, Use & Abuse, Portrayal, Commoditization. www.ijellh.com 14 Introduction Cinema and dance have had a long history of engagement. Cinema enlisted dance from its very beginnings – the spectacular display of movement. The shared investment in movement ensured a spontaneous intermediality (transgression of boundaries) between early cinema and dance. Songs with dance have always played a crucial role in Hindi movies. The role of song and its demand changed with the entry of „item songs‟. -

Baila

1. A song shot in one of these locations is an item number featuring women dressed in traditional North Indian clothing, despite being from South India. That song would later be remade for the movie Maximum, although it’s location was changed from one of these locations. That song shot in one of these locations repeatedly lists the name of cities, and was part of a breakout film for Allu Arjun. In addition to (*) Aa Ante Amalapuram, another song shot in one of these locations features a lyric that praises someone’s speech to be “as fine as the Urdu language.” Shahrukh Khan dances on top of, for 10 points, what location in Chaiyya Chaiyya? ANSWER: Train [accept railroad or railway or equivalents] <Bollywood> 2. This word is the name of a popular dance in Sri Lanka, and a song titled “[this word] Remix Karala” was remixed into the 2011 Sri Lankan Cricket Team’s song. Another song with this word in its title claims that this word “esta cumbia,” and is by Selena. A song with another conjugation of this word in its title says (*) “Nothing can stop us tonight” before the title phrase. That song featuring this word in its title also says “Te quiero, amor mio” before the title word is repeated in the chorus. For 10 points, name this word which titles an Enrique Iglesias song, in which it precedes and succeeds the phrase “Let the rhythm take you over.” ANSWER: baila [accept bailar or bailamos - meta tossup lul] <Latin American Music> 3. The second episode of the History Channel TV show UnXplained is partially set in this location. -

Karan Johar Shahrukh Khan Choti Bahu R. Madhavan Priyanka

THIS MONTH ON Vol 1, Issue 1, August 2011 Karan Johar Director of the Month Shahrukh Khan Actor of the Month Priyanka Chopra Actress of the Month Choti Bahu Serial of the Month R. Madhavan Host of the Month Movie of the Month HAUNTED 3D + What’s hot Kids section Gadget Review Music Masti VAS (Value Added Services) THIS MONTH ON CONTENTS Publisher and Editor-in-Chief: Anurag Batra Editorial Director: Amit Agnihotri Editor: Vinod Behl Directors: Nawal Ahuja, Ritesh Vohra, Kapil Mohan Dhingra Advisory Board Anuj Puri, (Chairman & Country Head, Jones Lang LaSalle India) Laxmi Goel, (Director, Zee News & Chairman, Suncity Projects) Ajoy Kapoor (CEO, Saffron Real Estate Management) Dr P.S. Rana, Ex-C( MD, HUDCO) Col. Prithvi Nath, (EVP, NAREDCO & Sr Advisor, DLF Group) Praveen Nigam, (CEO, Amplus Consulting) Dr. Amit Kapoor, (Professor in Strategy and nd I ustrial Economics, MDI, Gurgoan) Editorial Editorial Coordinating Editor : Vishal Duggal Assistant Editor : Swarnendu Biswas da con parunt, ommod earum sit eaqui ipsunt abo. Am et dias molup- Principal Correspondent : Vishnu Rageev R tur mo beressit rerum simpore mporit explique reribusam quidella Senior Correspondent : Priyanka Kapoor U Correspondents : Sujeet Kumar Jha, Rahul Verma cus, ommossi dicte eatur? Em ra quid ut qui tem. Saecest, qui sandiorero tem ipic tem que Design Art Director : Jasper Levi nonseque apeleni entustiori que consequ atiumqui re cus ulpa dolla Sr. Graphic Designers : Sunil Kumar preius mintia sint dicimi, que corumquia volorerum eatiature ius iniam res Photographe r : Suresh Gola cusapeles nieniste veristo dolore lis utemquidi ra quidell uptatiore seque Advertisment & Sales nesseditiusa volupta speris verunt volene ni ame necupta consequas incta Kapil Mohan Dhingra, [email protected], Ph: 98110 20077 sumque et quam, vellab ist, sequiam, amusapicia quiandition reprecus pos 3 Priya Patra, [email protected], Ph: 99997 68737, New Delhi Sneha Walke, [email protected], Ph: 98455 41143, Bangalore ute et, coressequod millaut eaque dis ariatquis as eariam fuga. -

Shool Report

MLA 8.0 QUICK STYLE GUIDE Cover Graphic Source: Plagiarism Wordle. Piedmont Virginia Community College. 8 Dec. 2015. http://libguides.pvcc.edu/plagiarism. Accessed 6 Jun. 2016. Alexander College Writing & Learning Centres, Winter 2018. Alexander College 1 MLA BASICS 2-5 Formatting Rules 2 Sample Page 1 3 What to Cite, Where to Cite 3 Figures and Tables 4-5 In-Text Citations – THE BASICS 6-7 Basic Formatting Rules for In-text citations 6 INDIRECT SOURCES: VERY IMPORTANT FOR RESEARCH PAPERS 6 Consecutive Citations 6-7 Block Quote 7 Works Cited – THE BASICS 7-8 Works Cited: the Basics 7 How to Cite: ONLINE RESOURCES 9-13 Journal Articles from Online Databases (EBSCO, Google Scholar, etc.) 9 Article: Online Newspaper or Magazine 9 Editorials from Online Newspaper or Magazine 10 E-Books 11 Articles from Websites 12 Online Dictionary or Encyclopedia 13 How to Cite: PRINT SOURCES 13-19 Books 14-15 Republished Books 15 Anthology (Collection) 16 Books by Organisations 16-17 Print Newspaper, Journal or Magazine 17-18 Class Notes 19 How to Cite: RECORDED MEDIA (FILMS, ETC.) 20-22 Movies 20-21 TV Series 21-22 YouTube Videos 22 How to Cite: PLAYS 23 Print Copies of Plays 23 Live Performances of Plays 23 SAMPLE WORKS CITED 24-25 Alexander College 2 This is a Quick Guide to MLA citations and references. It contains information on the basic formatting elements for MLA Style papers . It contains sample in-text citations and references entries for the resources most commonly used by students. If your Instructor gives specific instructions for format or citations, follow his or her guidelines. -

Luka Chuppi: Kartik Aaryan and Kriti Sanon's Film Plays Hide-And-Seek

13 SATURDAY, MARCH 2, 2019 2- TOTAL DHAMAAL (PG-13) (HINDI/COMEDY/ADVEN- 10-ALONE / TOGETHER (PG-15) (FILIPINO/ROMANTIC/ DAILY AT: 12.15 + 3.00 + 5.45 + 8.30 + (11.15 PM THURS/FRI) OASIS JUFFAIR TURE) NEW DRAMA) NEW AJAY DEVGN, MADHURI DIXIT, ANIL KAPOOR LIZA SOBERANO, ENRIQUE GIL, JASMINE CURTIS 3- THE KNIGHT OF SHADOWS: BETWEEN YIN AND 1-FIGHTING WITH MY FAMILY (15+) (DRAMA/COME- FROM THURSDAY 21ST 7.00 PM ONWARDS DAILY AT: 11.00 AM + 1.30 + 4.00 + 6.30 + 9.00 + 11.30 PM YANG (PG-13) (ACTION/COMEDY/FANTASY) NEW DY/BIOGRAPHY) NEW DAILY AT: 10.30 AM + 1.00 + 3.45 + 6.30 + 9.15 PM + 12.00 MN JACKIE CHAN, ELANE ZHONG, ETHAN JUAN DWAYNE JOHNSON, FLORENCE PUGH, JACK LOWDEN 11-ALITA: BATTLE ANGEL (PG-15) (ACTION/ADVEN- DAILY AT: 10.45 AM + 1.00 + 6.15 + (11.30 PM THURS/FRI) DAILY AT: 12.30 + 5.00 + 9.30 PM 3- DUMPLIN (15+) (COMEDY/DRAMA) NEW TURE/ROMANTIC) DAILY AT (VIP): 10.45 AM + 3.30 + 8.15 PM DANIELLE MACDONALD, JENNIFER ANISTON, ROSA SALAZAR, CHRISTOPH WALTZ, JENNIFER CONNELLY 4-ALITA: BATTLE ANGEL (PG-15) (ACTION/ADVEN- LUKE BENWARD DAILY AT: 11.30 AM + 2.00 + 4.30 + 7.00 + 9.30 PM + 12.00 MN TURE/ROMANTIC) 2-TOTAL DHAMAAL (PG-13) (HINDI/COMEDY/ADVEN- DAILY AT: 12.00 + 2.15 + 4.30 + 6.45 + 9.00 + 11.15 PM ROSA SALAZAR, CHRISTOPH WALTZ, JENNIFER CONNELLY TURE) NEW 12-GULLY BOY (PG-15) (HINDI/DRAMA/MUSICAL) DAILY AT: 6.00 + 8.30 + (11.00 PM THURS/FRI) AJAY DEVGN, MADHURI DIXIT, ANIL KAPOOR 4- UPGRADE (15+) (ACTION/THRILLER) NEW ALIA BHAT, RANVEER SINGH, SIDDHANT CHATURVEDI FROM THURSDAY 21ST 7.00 PM ONWARDS LOGAN MARSHALL-GREEN, RICHARD -

India Financial Statement

Many top stars donated their time to PETA in elementary school students why elephants don’t order to help focus public attention on cruelty belong in circuses. PETA India’s new petition calling India to animals. Bollywood “villain” Gulshan Grover’s on the government to uphold the ban on jallikattu – sexy PETA ad against leather was released ahead a bull-taming event in which terrified bulls are Financial Statement of Amazon India Fashion Week. Pamela Anderson deliberately disoriented, punched, jumped on, penned a letter to the Chief Minister of Kerala to offer tormented, stabbed and dragged to the ground – REVENUES 30 life-size, realistic and portable elephants made of has been signed by top film stars, including Contributions 71,098,498 bamboo and papier-mâché to replace live elephants in Sonakshi Sinha, Jacqueline Fernandez, Other Income 335,068 the Thrissur Pooram parade. Tennis player Sania Mirza Bipasha Basu, John Abraham, Raveena Tandon, and the stars of Comedy Nights With Kapil teamed Vidyut Jammwal, Shilpa Shetty, Kapil Sharma, Total Revenues 71,433,566 up with PETA for ads championing homeless cat and Amy Jackson, Athiya Shetty, Sonu Sood, dog adoption. Kapil Sharma, the host of that show, Richa Chadha and Vidya Balan and cricketers was also named PETA’s 2015 Person of the Year for Virat Kohli and Shikhar Dhawan. OPERATING EXPENSES his dedication to Programmes helping animals. PETA gave a Awareness Programme 37,434,078 Just before Humane Science Compassionate Citizen Project 3,998,542 World Music Award to the Membership Development 13,175,830 Day, members Mahatma Gandhi- Management and General Expenses 16,265,248 of folk band Doerenkamp The Raghu Centre, for their Dixit Project monumental Total Operating Expenses 70,873,698 starred in a PETA progress in Youth campaign pushing for ad against cruelty humane legislation CHANGE IN NET ASSETS 559,868 to animals in Photo: © Guarav Sawn and reducing and Net Assets Beginning of Year 5,086,144 the circus. -

Akshay Kumar

Akshay Kumar Topic relevant selected content from the highest rated wiki entries, typeset, printed and shipped. Combine the advantages of up-to-date and in-depth knowledge with the convenience of printed books. A portion of the proceeds of each book will be donated to the Wikimedia Foundation to support their mis- sion: to empower and engage people around the world to collect and develop educational content under a free license or in the public domain, and to disseminate it effectively and globally. The content within this book was generated collaboratively by volunteers. Please be advised that nothing found here has necessarily been reviewed by people with the expertise required to provide you with complete, accu- rate or reliable information. Some information in this book maybe misleading or simply wrong. The publisher does not guarantee the validity of the information found here. If you need specific advice (for example, medi- cal, legal, financial, or risk management) please seek a professional who is licensed or knowledgeable in that area. Sources, licenses and contributors of the articles and images are listed in the section entitled “References”. Parts of the books may be licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. A copy of this license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License” All used third-party trademarks belong to their respective owners. Contents Articles Akshay Kumar 1 List of awards and nominations received by Akshay Kumar 8 Saugandh 13 Dancer (1991 film) 14 Mr Bond 15 Khiladi 16 Deedar (1992 film) 19 Ashaant 20 Dil Ki Baazi 21 Kayda Kanoon 22 Waqt Hamara Hai 23 Sainik 24 Elaan (1994 film) 25 Yeh Dillagi 26 Jai Kishen 29 Mohra 30 Main Khiladi Tu Anari 34 Ikke Pe Ikka 36 Amanaat 37 Suhaag (1994 film) 38 Nazar Ke Samne 40 Zakhmi Dil (1994 film) 41 Zaalim 42 Hum Hain Bemisaal 43 Paandav 44 Maidan-E-Jung 45 Sabse Bada Khiladi 46 Tu Chor Main Sipahi 48 Khiladiyon Ka Khiladi 49 Sapoot 51 Lahu Ke Do Rang (1997 film) 52 Insaaf (film) 53 Daava 55 Tarazu 57 Mr. -

Anselm Kiefer

PRESENTS Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow A film by Sophie Fiennes 2010 / France, U.K. and Netherlands / 105 min. / 2.35:1 / Dolby-Surround-DTS / Not Rated In German with English subtitles An Alive Mind Cinema Release from Kino Lorber, Inc. 333 W. 39st St., Suite 503 New York, NY 10018 (212) 629-6880 Publicity Contact: Rodrigo Brandão Director of Publicity Kino Lorber, Inc. (212) 629-6880 ext. 12 [email protected] About Kasander Film: KEES KASANDER set up Kasander Film for the purpose of structural European crossover productions. He is mostly known for his work with Peter Greenaway; THE COOK, THE THIEF, HIS WIFE AND HER LOVER (1989), PROSPERO'S BOOKS (1992) and THE PILLOW BOOK (1995). His newest feature film FISH TANK written and directed by Andrea Arnold premiered at the Cannes Film Festival 2009 and received the Jury Prize. On top of that FISH TANK was rewarded with a BAFTA award for Best Outstanding British Film in February 2010. About Sciapode: SCIAPODE was founded in 2003 to produce European films by strong and ambitious filmmakers. These artists – Sophie Fiennes, Wim Vandekeybus, Andrew Kötting, Wayn Traub, Jan Lauwers, Michael Roskam, Frédérique Devillez, Florent de la Tullaye, David Dusa, Renaud Barret, Philipp Mayrhofer, Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker... – experienced film making but also, for some of them visual arts, choreography, theatre, opera, possibly mixing different media for a richer work and new narrative style. About Emile Blezat: Producer Emile Blezat graduated from the High Business School of Paris (ESCP) and obtained a Master (MBA) in Entrepreneurship, Project Development and Negotiation at Olin Graduate Shool of Business (Boston). -

Making Women Visible: Gender and Race Cross-Dressing in the Parsi Theatre Author(S): Kathryn Hansen Source: Theatre Journal, Vol

Making Women Visible: Gender and Race Cross-Dressing in the Parsi Theatre Author(s): Kathryn Hansen Source: Theatre Journal, Vol. 51, No. 2 (May, 1999), pp. 127-147 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25068647 Accessed: 13/06/2009 19:04 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=jhup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Theatre Journal. http://www.jstor.org Making Women Visible: Gender and Race Cross-Dressing in the Parsi Theatre Kathryn Hansen Over the last century the once-spurned female performer has been transformed into a ubiquitous emblem of Indian national culture.