The Efficacy of Comedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speaking of South Park

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 3 May 15th, 9:00 AM - May 17th, 5:00 PM Speaking of South Park Christina Slade University Sydney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Slade, Christina, "Speaking of South Park" (1999). OSSA Conference Archive. 53. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA3/papersandcommentaries/53 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Title: Speaking of South Park Author: Christina Slade Response to this paper by: Susan Drake (c)2000 Christina Slade South Park is, at first blush, an unlikely vehicle for the teaching of argumentation and of reasoning skills. Yet the cool of the program, and its ability to tap into the concerns of youth, make it an obvious site. This paper analyses the argumentation of one of the programs which deals with genetic engineering. Entitled 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig', the episode begins with the elephant being presented to the school bus driver as 'the new disabled kid'; and opens a debate on the virtues of genetic engineering with the teacher saying: 'We could have avoided terrible mistakes, like German people'. The show both offends and ridicules received moral values. However a fine grained analysis of the transcript of 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig' shows how superficially absurd situations conceal sophisticated argumentation strategies. -

South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review

south park the fractured but whole free download review South park the fractured but whole free download review. South Park The Fractured But Whole Crack Whole, players with Coon and Friends can dive into the painful, criminal belly of South Park. This dedicated group of criminal warriors was formed by Eric Cartman, whose superhero alter ego, The Coon, is half man, half raccoon. Like The New Kid, players will join Mysterion, Toolshed, Human Kite, Mosquito, Mint Berry Crunch, and a group of others to fight the forces of evil as Coon strives to make his team of the most beloved superheroes in history. Creators Matt South Park The Fractured But Whole IGG-Game Stone and Trey Parker were involved in every step of the game’s development. And also build his own unique superpowers to become the hero that South Park needs. South Park The Fractured But Whole Codex The player takes on the role of a new kid and joins South Park favorites in a new extremely shocking adventure. The game is the sequel to the award-winning South Park The Park of Truth. The game features new locations and new characters to discover. The player will investigate the crime under South Park. The other characters will also join the player to fight against the forces of evil as the crown strives to make his team the most beloved South Park The Fractured But Whole Plaza superheroes in history. Try Marvel vs Capcom Infinite for free now. The all-new dynamic control system offers new possibilities to manipulate time and space on the battlefield. -

South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, the Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2009-01-01 South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Dungan, Drew W., "South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism" (2009). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 245. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/245 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan Department of Communication APPROVED: Richard D. Pineda, Ph.D., Chair Stacey Sowards, Ph.D. Robert L. Gunn, Ph.D. Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Drew W. Dungan 2009 Dedication To all who have been patient and kind, most of all Robert, Thalia, and Jesus, thank you for everything... South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies. The Art of Stealthy Conservatism by DREW W. DUNGAN, B.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2009 Abstract South Park serves as an example of satire and parody lampooning culture war issues in the popular media. -

Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2016 Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Elrick, Kathy, "Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News" (2016). All Dissertations. 1847. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC FEMINISM: RHETORICAL CRITIQUE IN SATIRICAL NEWS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Kathy Elrick December 2016 Accepted by Dr. David Blakesley, Committee Chair Dr. Jeff Love Dr. Brandon Turner Dr. Victor J. Vitanza ABSTRACT Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News aims to offer another perspective and style toward feminist theories of public discourse through satire. This study develops a model of ironist feminism to approach limitations of hegemonic language for women and minorities in U.S. public discourse. The model is built upon irony as a mode of perspective, and as a function in language, to ferret out and address political norms in dominant language. In comedy and satire, irony subverts dominant language for a laugh; concepts of irony and its relation to comedy situate the study’s focus on rhetorical contributions in joke telling. How are jokes crafted? Who crafts them? What is the motivation behind crafting them? To expand upon these questions, the study analyzes examples of a select group of popular U.S. -

PDF Download South Park Drawing Guide : Learn To

SOUTH PARK DRAWING GUIDE : LEARN TO DRAW KENNY, CARTMAN, KYLE, STAN, BUTTERS AND FRIENDS! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Go with the Flo Books | 100 pages | 04 Dec 2015 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781519695369 | English | none South Park Drawing Guide : Learn to Draw Kenny, Cartman, Kyle, Stan, Butters and Friends! PDF Book Meanwhile, Butters is sent to a special camp where they "Pray the Gay Away. See more ideas about south park, south park anime, south park fanart. After a conversation with God, Kenny gets brought back to life and put on life support. This might be why there seems to be an air of detachment from Stan sometimes, either as a way to shake off hurt feelings or anger and frustration boiling from below the surface. I was asked if I could make Cartoon Animals. Whittle his Armor down and block his high-powered attacks and you'll bring him down, faster if you defeat Sparky, which lowers his defense more, which is recommended. Butters ends up Even Butters joins in when his T. Both will use their boss-specific skill on their first turn. Garrison wielding an ever-lively Mr. Collection: Merry Christmas. It is the main protagonists in South Park cartoon movie. Climb up the ladder and shoot the valve. Donovan tells them that he's in the backyard. He can later be found on the top ramp and still be aggressive, but cannot be battled. His best friend is Kyle Brovlovski. Privacy Policy.. To most people, South Park will forever remain one of the quirkiest and wittiest animated sitcoms created by two guys who can't draw well if their lives depended on it. -

PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues Through Satire

Colloquy Vol. 12, Fall 2016, pp. 101-114 PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues through Satire Alex Dejean Abstract This study takes an extensive look at the television program South Park episode “Stunning and Brave.” There is limited research that explores the use of satire to create social discourse on concepts related to political correctness. I use framing theory as a primary variable to understand the messages “Stunning and Brave” attempts to convey. Framing theory originated from the theory of agenda setting. Agenda setting explains how media depictions affect how people think about the world. Framing is an aspect of agenda setting that details the organization and structure of a narrative or story. Framing is such an important variable to agenda setting that research on framing has become its own field of study. Existing literature of framing theory, comedy, and television has shown how audiences perceive issues once they have been exposed to media messages. The purpose of this research will review relevant literature explored in this area to examine satirical criticism on the social issue of political correctness. It seems almost unnecessary to point out the effect media has on us every day. Media is a broad term for the collective entities and structures through which messages are created and transmitted to an audience. As noted by Semmel (1983), “Almost everyone agrees that the mass media shape the world around us” (p. 718). The media tells us what life is or what we need for a better life. We have been bombarded with messages about what is better. -

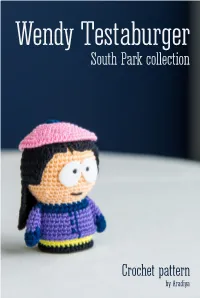

Eng Tutorial Wendy

Wendy Testaburger South Park collection Crochet pattern by Aradiya 1 Instruments and materials 1.25 and 2.00 mm hooks Purple, navy blue, pink, flesh-colored, yellow and black yarn Sewing needle Stung material A piece of white felt Image 1 Wendy Testaburger - character of the popular cartoon “South Park”. To create a toy with a height of 7.5 cm you must crochet with single yarn using a 2.00 mm hook. The arms, the hair and the hat are crocheted with single yarn using a 1.25 mm hook. The stung material used in this toy is polyester wadding. The piece of felt must be 1.5 mm thick. This pattern is for personal use only. Sharing information from this pattern is prohibited. If you publish photos of the toys that are crocheted following this pattern, it is better to mention the author of the pattern. You can also use hashtag #AradiyaToys at Twitter and Instagram to share your toy and see other toys that are created following AradiyaToys’ patterns. 2 Abbreviations Ch - chain Sl - slip stitch Sc - single crochet Dc - double crochet HDc - half double crochet INC - increase INVDEC - invisible decrease BLO - back loops only FLO - front loops only Tip 1 The toy must be All amigurumi toys crocheted with tight are crocheted with tight stitches. Avoid stitches, to be sure that small holes when there won't be any holes stretching crochet through which stung fabric, if there are material can some tiny holes, be seen. use a smaller size hook. To avoid seams, all details are crocheted in a spiral without slip stitch and lifting loops. -

Cartman Will Not Be Silenced in an All-New Episode of 'South Park' Premiering on Wednesday, November 11 at 10:00 P.M

Cartman Will Not Be Silenced in an All-New Episode of 'South Park' Premiering on Wednesday, November 11 at 10:00 p.m. on COMEDY CENTRAL(R) NEW YORK, Nov 09, 2009 -- Cartman has a daily forum for his agenda when he is chosen to do the morning announcements at school in an all-new "South Park" titled, "Dances with Smurfs," premiering on Wednesday, November 11 at 10:00 p.m. on COMEDY CENTRAL. Eric Cartman seizes the opportunity to become the voice of change at the school when he takes over the morning announcements. His target is South Park Elementary's Student Body President, Wendy Testaburger. Cartman is asking the tough questions and gaining followers. Launched in 1997, "South Park," now in its 13th season, remains the highest-rated series on COMEDY CENTRAL. "South Park" repeats Wednesdays at 12:00 a.m., Thursdays at 10:00 p.m. and 12:00 a.m. and Sundays at 11:00 p.m. and 2:00 a.m. Co-creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone are executive producers, along with Anne Garefino, of the Emmy® and Peabody® Award-winning "South Park." Frank C. Agnone II is the supervising producer. Eric Stough, Adrien Beard, Bruce Howell, Vernon Chatman and Erica Rivinoja are producers. "South Park's" Web site is www.southparkstudios.com. COMEDY CENTRAL, the only all-comedy network, currently is seen in more than 95 million homes nationwide. COMEDY CENTRAL is owned by, and is a registered trademark of, Comedy Partners, a wholly-owned division of Viacom Inc.'s (NYSE: VIA and VIA.B) MTV Networks. -

Soyouwanna Do Stand-Up Comedy? | Soyouwanna.Com 10/10/09 10:42 AM

SoYouWanna do stand-up comedy? | SoYouWanna.com 10/10/09 10:42 AM Search SYW SYWs SYWs by Questions How Tos HOME A to Z CATEGORY & Answers Sponsored Links Related Ads Comedian Casting Frank Caliendo in Vegas Comedy Circus Auditions, Open Calls for Comedian Add Laughter to Your Vegas Trip. Buy Def Comedy Jam Jobs.Talent Needed Urgently Frank Caliendo Tickets Today! Funny Comedy Casting-Call.us/Comedian www.MonteCarlo.com/FrankCaliendo Comedians Stand Up Comedy SOYOUWANNA DO STAND-UP COMEDY? Comedy Songs be a movie extra? get a talent agent? 1. Study the pros know about different fabrics 2. Gather material for your act for men's suits? write an impressive 3. Turn your material into a stand-up resume? routine register a trademark? 4. Find a place to perform 5. Earn money for being funny Sponsored Links Improv Comedy SF Bay Area Shows and Classes. Perform or watch Yeah, yeah, you're pretty funny. But it's one thing to make some of your slightly buzzed Only one block from friends laugh at a party. It's a whole other ballgame to get on a stage in front of an 19th BART audience and do stand-up comedy. To do any kind of live performance, you need to have www.pantheater.com a strong ego and nerves of steel. To do stand-up comedy, you need to be virtually insane. Almost everybody bombs their first time ("bombing" means that you didn't make 'em laugh . in the world of stand-up, that's not good). Learn Stand Up Comedy There's a common misconception that stand-up comics do nothing all day and tell little stories to drunken audiences at night. -

Marketing Fundamentals

Comedy and Performance 197g Fall Semester 2017 Tuesday and Thursday 2.00 – 3.20pm Location: LVL 17 Instructor: Louise Peacock Office: JEF 202 Office Hours: Tuesday and Thursday 10 – 11. Please contact me for appointments. Contact Info: [email protected] Teaching Assistant or Assistant Instructors: Ashley Steed. Contact Info: [email protected] Jay Lee Contact Info: [email protected] Course Description and Overview This GE course will provide students with an overview and understanding of the history and performance of comedy. Using examples from as far back as Greek Theatre and as current as Modern Family, students will be encouraged to identify and understand the distinctive features, techniques and themes of comedy performance. Through many manifestations including the pantomimes of the Greek and Roman periods, the Commedia dell’Arte of the Renaissance, the flourishing of the circus, the great age of silent comedy in cinema, and the postwar screen era, comedy in performance has evolved in multiple forms as a response to prevailing conditions while maintaining many primary functions, including satire, celebration, and social commentary. The course explores in depth many of the most important and influential periods and differing strains of comic performance, addressing the discipline in terms of creation and execution as envisaged by writers, actors, clowns, comedians, and directors. Learning Objectives 1. To analyze the form and content of comic material across a range of historic periods and to investigate the impact of comedy on audiences 2. To make connections between the comedy of different periods, identifying the social, political and cultural contexts in which the work was created and performed. -

Taming Distraction: the Second Screen Assemblage, Television

Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183-2439) 2016, Volume 4, Issue 3, Pages 185-198 Doi: 10.17645/mac.v4i3.538 Article Taming Distraction: The Second Screen Assemblage, Television and the Classroom Markus Stauff Media Studies Department, University of Amsterdam, 1012 XT, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 19 December 2015 | Accepted: 18 April 2016 | Published: 14 July 2016 Abstract This article argues that television’s resilience in the current media landscape can best be understood by analyzing its role in a broader quest to organize attention across different media. For quite a while, the mobile phone was consid- ered to be a disturbance both for watching television and for classroom teaching. In recent years, however, strategies have been developed to turn the second screen’s distractive potential into a source for intensified, personalized and social attention. This has consequences for television’s position in a multimedia assemblage: television’s alleged speci- ficities (e.g. liveness) become mouldable features, which are selectively applied to guide the attention of users across different devices and platforms. Television does not end, but some of its traditional features do only persist because of its strategic complementarity with other media; others are re-adapted by new technologies thereby spreading televisu- al modes of attention across multiple screens. The article delineates the historical development of simultaneous media use as a ‘problematization’—from alternating (and competitive) media use to multitasking and finally complementary use of different media. Additionally, it shows how similar strategies of managing attention are applied in the ‘digital classroom’. While deliberately avoiding to pin down, what television is, the analysis of the problem of attention allows for tracing how old and new media features are constantly reshuffled. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 28 March 2016 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Miles, Sarah (2013) 'Staging and constructing the divine in Menander.', in Menander in contexts. New York: Routledge, pp. 75-89. Routledge monographs in classical studies. (16). Further information on publisher's website: http://www.routledge.com/9780415843713 Publisher's copyright statement: Copyright c 2013 From Menander in Contexts, Edited by Alan H. Sommerstein. Reproduced by permission of Taylor and Francis Group, LLC, a division of Informa plc. This material is strictly for personal use only. For any other use, the user must contact Taylor Francis directly at this address: [email protected]. Printing, photocopying, sharing via any means is a violation of copyright. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk STAGING AND CONSTRUCTING THE DIVINE IN MENANDER ABSTRACT The chapter explores Menander’s dramatisation of divine characters and asks: what was the significance for Menander’s original audiences of seeing divinities on-stage? Through analysing Menander’s engagement with the dramatic tradition of portraying gods, the chapter suggests that Menander exploits his audience’s familiarity with dramatic setting and religious contexts to bring the audience into a closer relationship with the divine.