Ethernet Basics Rev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Ttethernet for Integrated Fault-Tolerant Spacecraft Networks

On TTEthernet for Integrated Fault-Tolerant Spacecraft Networks Andrew Loveless∗ NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX, 77058 There has recently been a push for adopting integrated modular avionics (IMA) princi- ples in designing spacecraft architectures. This consolidation of multiple vehicle functions to shared computing platforms can significantly reduce spacecraft cost, weight, and de- sign complexity. Ethernet technology is attractive for inclusion in more integrated avionic systems due to its high speed, flexibility, and the availability of inexpensive commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components. Furthermore, Ethernet can be augmented with a variety of quality of service (QoS) enhancements that enable its use for transmitting critical data. TTEthernet introduces a decentralized clock synchronization paradigm enabling the use of time-triggered Ethernet messaging appropriate for hard real-time applications. TTEther- net can also provide two forms of event-driven communication, therefore accommodating the full spectrum of traffic criticality levels required in IMA architectures. This paper explores the application of TTEthernet technology to future IMA spacecraft architectures as part of the Avionics and Software (A&S) project chartered by NASA's Advanced Ex- ploration Systems (AES) program. Nomenclature A&S = Avionics and Software Project AA2 = Ascent Abort 2 AES = Advanced Exploration Systems Program ANTARES = Advanced NASA Technology Architecture for Exploration Studies API = Application Program Interface ARM = Asteroid Redirect Mission -

Securing the Everywhere Perimeter Iot, BYOD, and Cloud Have Fragmented the Traditional Network Perimeter

White Paper Securing the Everywhere Perimeter IoT, BYOD, and Cloud have fragmented the traditional network perimeter. This revolution necessitates a new approach that is comprehensive, pervasive, and automated. Businesses need an effective strategy to differentiate critical applications and confidential data, partition user and devices, establish policy boundaries, and reduce their exposure. Leveraging Extreme Networks technology, organizations can hide much of their network and protect those elements that remain visible. Borders are established that defend against unauthorized lateral movement, the attack profile is reduced, and highly effective breach isolation is delivered. This improves the effectiveness of anomaly scanning and the value of specialist security appliances. Redundant network configuration is rolled back, leaving an edge that is “clean” and protected from hacking. Businesses avoid many of the conventional hooks and tools that hackers seek to exploit. Additionally, flipping the convention of access-by-default, effective access control policy enforcement denies unauthorized connectivity. The Business Imperative As businesses undertake the digital transformation, the trends of cloud, mobility, and IoT converge. Organizations need to take a holistic approach to protecting critical systems and data, and important areas for attention are the ability to isolate traffic belonging to different applications, to reduce the network’s exposure and attack profile, and to dynamically control connectivity to network assets. In addition to all of the normal challenges and demands, businesses are also starting to experience IoT. This networking phenomenon sees unconventional embedded system devices appearing, seemingly from nowhere, requiring connectivity. WWW.EXTREMENETWORKS.COM 1 IoT is being positioned as the enabling technology for all manner of “Smart” initiatives. -

Mikrodenetleyicili Endüstriyel Seri Protokol Çözümleyici Sisteminin Programi

YILDIZ TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ FEN BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ MİKRODENETLEYİCİLİ ENDÜSTRİYEL SERİ PROTOKOL ÇÖZÜMLEYİCİ SİSTEMİNİN PROGRAMI Elektronik ve Haberleşme Müh. Kemal GÜNSAY FBE Elektronik ve Haberleşme Anabilim Dalı Elektronik Programında Hazırlanan YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ Tez Danışmanı : Yrd. Doç. Dr. Tuncay UZUN (YTÜ) İSTANBUL, 2009 YILDIZ TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ FEN BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ MİKRODENETLEYİCİLİ ENDÜSTRİYEL SERİ PROTOKOL ÇÖZÜMLEYİCİ SİSTEMİNİN PROGRAMI Elektronik ve Haberleşme Müh. Kemal GÜNSAY FBE Elektronik ve Haberleşme Anabilim Dalı Elektronik Programında Hazırlanan YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ Tez Danışmanı : Yrd. Doç. Dr. Tuncay UZUN (YTÜ) İSTANBUL, 2009 İÇİNDEKİLER Sayfa KISALTMA LİSTESİ ................................................................................................................ v ŞEKİL LİSTESİ ...................................................................................................................... viii ÇİZELGE LİSTESİ .................................................................................................................... x ÖNSÖZ ...................................................................................................................................... xi ÖZET ........................................................................................................................................ xii ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................ xiii 1. GİRİŞ ...................................................................................................................... -

How to Set up IP Camera by Using a Macintosh Computer

EDIMAX COMPUTER INC. Edimax IP Camera series How to set up IP Camera by using a Macintosh computer 2011 Edimax Computer 3350 Scott Blvd., Building #15 Santa Clara, California 95054, USA Phone 408-496-1105 • Fax 408-980-1530 www.edimax.us How to setup Edimax IP Camera by a Macintosh computer Introduction The most important thing to setup IP Camera is to assign a static IP address so the camera can work with your network. So far the Edimax IP Cam Admin utility is Windows based only and the program can not work for Macintosh computers. Macintosh users can follow this guide to set up Edimax IP camera. Step 1. Understand the IP address used in your network. Have your Macintosh computer operate as usual. Go into System Preferences. In System Preferences, Go to Network. Select the adapter you are using. It could be an Airport card, a third- party Wireless card, or an Ethernet Adapter. Write down the IP address, subnet mask, Router, and DNS server address. We have a usb wireless card in this example. Its IP address 10.0.1.2 told us that the IP addresses used in the network are 10.0.1.x. All the devices in the network have the first three octets the same, but the last octet number must be different. We decide to give our new camera an IP address 10.0.1.100 because no other computer device use 10.0.1.100. We temporarily disconnect the wireless adapter. You can turn off your Airport adapter if you use it to get on Internet. -

Gigabit Ethernet - CH 3 - Ethernet, Fast Ethernet, and Gigabit Ethern

Switched, Fast, and Gigabit Ethernet - CH 3 - Ethernet, Fast Ethernet, and Gigabit Ethern.. Page 1 of 36 [Figures are not included in this sample chapter] Switched, Fast, and Gigabit Ethernet - 3 - Ethernet, Fast Ethernet, and Gigabit Ethernet Standards This chapter discusses the theory and standards of the three versions of Ethernet around today: regular 10Mbps Ethernet, 100Mbps Fast Ethernet, and 1000Mbps Gigabit Ethernet. The goal of this chapter is to educate you as a LAN manager or IT professional about essential differences between shared 10Mbps Ethernet and these newer technologies. This chapter focuses on aspects of Fast Ethernet and Gigabit Ethernet that are relevant to you and doesn’t get into too much technical detail. Read this chapter and the following two (Chapter 4, "Layer 2 Ethernet Switching," and Chapter 5, "VLANs and Layer 3 Switching") together. This chapter focuses on the different Ethernet MAC and PHY standards, as well as repeaters, also known as hubs. Chapter 4 examines Ethernet bridging, also known as Layer 2 switching. Chapter 5 discusses VLANs, some basics of routing, and Layer 3 switching. These three chapters serve as a precursor to the second half of this book, namely the hands-on implementation in Chapters 8 through 12. After you understand the key differences between yesterday’s shared Ethernet and today’s Switched, Fast, and Gigabit Ethernet, evaluating products and building a network with these products should be relatively straightforward. The chapter is split into seven sections: l "Ethernet and the OSI Reference Model" discusses the OSI Reference Model and how Ethernet relates to the physical (PHY) and Media Access Control (MAC) layers of the OSI model. -

IEEE 802.1Aq Standard, Is a Computer Networking Technology Intended to Simplify the Creation and Configuration of Networks, While Enabling Multipath Routing

Brought to you by: Brian Miller Yuri Spillman - Specified in the IEEE 802.1aq standard, is a computer networking technology intended to simplify the creation and configuration of networks, while enabling multipath routing. - Link State Protocol - Based on IS-IS -The standard is the replacement for the older spanning tree protocols such as IEEE 802.1D, IEEE 802.1w, and IEEE 802.1s. These blocked any redundant paths that could result in layer 2(Data Link Layer), whereas IEEE 802.1aq allows all paths to be active with multiple equal cost paths, and provides much larger layer 2 topologies. 802.1aq is an amendment to the "Virtual Bridge Local Area Networks“ and adds Shortest Path Bridging (SPB). Shortest path bridging, which is undergoing IEEE’s standardization process, is meant to replace the spanning tree protocol (STP). STP was created to prevent bridge loops by allowing only one path between network switches or ports. When a network segment goes down, an alternate path is chosen and this process can cause unacceptable delays in a data center network. The ability to use all available physical connectivity, because loop avoidance uses a Control Plane with a global view of network topology Fast restoration of connectivity after failure, again because of Link State routing's global view of network topology Under failure, the property that only directly affected traffic is impacted during restoration; all unaffected traffic just continues Ideas are rejected by IEEE 802.1. accepted by the IETF and the TRILL WG is formed. Whoops, there is a problem. They start 802.1aq for spanning tree based shortest path bridging Whoops, spanning tree doesn’t hack it. -

Ethernet and Wifi

Ethernet and WiFi hp://xkcd.com/466/ CSCI 466: Networks • Keith Vertanen • Fall 2011 Overview • Mul?ple access networks – Ethernet • Long history • Dominant wired technology – 802.11 • Dominant wireless technology 2 Classic Ethernet • Ethernet – luminferous ether through which electromagne?c radiaon once thought to propagate – Carrier Sense, Mul?ple Access with Collision Detec?on (CSMA/CD) – IEEE 802.3 Robert Metcalfe, co- inventor of Ethernet 3 Classic Ethernet • Ethernet – Xerox Ethernet standardized as IEEE 802.3 in 1983 – Xerox not interested in commercializing – Metcalfe leaves and forms 3Com 4 Ethernet connec?vity • Shared medium – All hosts hear all traffic on cable – Hosts tapped the cable – 2500m maximum length – May include repeaters amplifying signal – 10 Mbps bandwidth 5 Classic Ethernet cabling Cable aSer being "vampire" tapped. Thick Ethernet cable (yellow), 10BASE-5 transceivers, cable tapping tool (orange), 500m maximum length. Thin Ethernet cable (10BASE2) with BNC T- connector, 185m maximum length. 6 Ethernet addressing • Media Access Control address (MAC) – 48-bit globally unique address • 281,474,976,710,656 possible addresses • Should last ?ll 2100 • e.g. 01:23:45:67:89:ab – Address of all 1's is broadcast • FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF 7 Ethernet frame format • Frame format – Manchester encoded – Preamble products 10-Mhz square wave • Allows clock synch between sender & receiver – Pad to at least 64-bytes (collision detec?on) Ethernet 802.3 AlternaWng 0's 48-bit MAC and 1's (except addresses SoF of 11) 8 Ethernet receivers • Hosts listens to medium – Deliver to host: • Any frame with host's MAC address • All broadcast frames (all 1's) • Mul?cast frames (if subscribed to) • Or all frames if in promiscuous mode 9 MAC sublayer • Media Access Control (MAC) sublayer – Who goes next on a shared medium – Ethernet hosts can sense if medium in use – Algorithm for sending data: 1. -

Ethercat – Ultra-Fast Communication Standard

EtherCAT – ultra-fast communication standard In 2003, Beckhoff introduces its EtherCAT tech- In 2007, EtherCAT is adopted as an IEC standard, EtherCAT: nology into the market. The EtherCAT Technology underscoring how open the system is. To this Group (ETG) is formed, supported initially by day, the specification remains unchanged; it has global standard 33 founder members. The ETG goes on to stan- only been extended and compatibility has been dardize and maintain the technology. The group is retained. As a result, devices from the early years, the largest fieldbus user organization in the world, even from as far back as 2003, are still interopera- for real-time with more than 5000 members (as of 2019) cur- ble with today’s devices in the same networks. rently. In 2005, the Safety over EtherCAT protocol Another milestone is achieved in 2016 Ethernet from the is rolled out, expanding the EtherCAT specification with EtherCAT P, which introduces the ability to to enable safe transmission of safety-relevant carry power (2 x 24 V) on a standard Cat.5 cable field to the I/Os control data. The low-footprint protocol uses a alongside EtherCAT data. This paves the way for so-called Black Channel, making it completely machines without control cabinets. independent of the communication system used. The launch of EtherCAT G/G10 in 2018 in- How it works The key functional principle of EtherCAT lies in how its nodes process Ethernet frames: each node reads the data addressed to it and writes its data back to Flexible topology the frame all while the frame is An EtherCAT network can sup- moving downstream. -

Introduction to Spanning Tree Protocol by George Thomas, Contemporary Controls

Volume6•Issue5 SEPTEMBER–OCTOBER 2005 © 2005 Contemporary Control Systems, Inc. Introduction to Spanning Tree Protocol By George Thomas, Contemporary Controls Introduction powered and its memory cleared (Bridge 2 will be added later). In an industrial automation application that relies heavily Station 1 sends a message to on the health of the Ethernet network that attaches all the station 11 followed by Station 2 controllers and computers together, a concern exists about sending a message to Station 11. what would happen if the network fails? Since cable failure is These messages will traverse the the most likely mishap, cable redundancy is suggested by bridge from one LAN to the configuring the network in either a ring or by carrying parallel other. This process is called branches. If one of the segments is lost, then communication “relaying” or “forwarding.” The will continue down a parallel path or around the unbroken database in the bridge will note portion of the ring. The problem with these approaches is the source addresses of Stations that Ethernet supports neither of these topologies without 1 and 2 as arriving on Port A. This special equipment. However, this issue is addressed in an process is called “learning.” When IEEE standard numbered 802.1D that covers bridges, and in Station 11 responds to either this standard the concept of the Spanning Tree Protocol Station 1 or 2, the database will (STP) is introduced. note that Station 11 is on Port B. IEEE 802.1D If Station 1 sends a message to Figure 1. The addition of Station 2, the bridge will do ANSI/IEEE Std 802.1D, 1998 edition addresses the Bridge 2 creates a loop. -

Gigabit Ethernet

Ethernet Technologies and Gigabit Ethernet Professor John Gorgone Ethernet8 Copyright 1998, John T. Gorgone, All Rights Reserved 1 Topics • Origins of Ethernet • Ethernet 10 MBS • Fast Ethernet 100 MBS • Gigabit Ethernet 1000 MBS • Comparison Tables • ATM VS Gigabit Ethernet •Ethernet8SummaryCopyright 1998, John T. Gorgone, All Rights Reserved 2 Origins • Original Idea sprang from Abramson’s Aloha Network--University of Hawaii • CSMA/CD Thesis Developed by Robert Metcalfe----(1972) • Experimental Ethernet developed at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center---1973 • Xerox’s Alto Computers -- First Ethernet Ethernet8systemsCopyright 1998, John T. Gorgone, All Rights Reserved 3 DIX STANDARD • Digital, Intel, and Xerox combined to developed the DIX Ethernet Standard • 1980 -- DIX Standard presented to the IEEE • 1980 -- IEEE creates the 802 committee to create acceptable Ethernet Standard Ethernet8 Copyright 1998, John T. Gorgone, All Rights Reserved 4 Ethernet Grows • Open Standard allows Hardware and Software Developers to create numerous products based on Ethernet • Large number of Vendors keeps Prices low and Quality High • Compatibility Problems Rare Ethernet8 Copyright 1998, John T. Gorgone, All Rights Reserved 5 What is Ethernet? • A standard for LANs • The standard covers two layers of the ISO model – Physical layer – Data link layer Ethernet8 Copyright 1998, John T. Gorgone, All Rights Reserved 6 What is Ethernet? • Transmission speed of 10 Mbps • Originally, only baseband • In 1986, broadband was introduced • Half duplex and full duplex technology • Bus topology Ethernet8 Copyright 1998, John T. Gorgone, All Rights Reserved 7 Components of Ethernet • Physical Medium • Medium Access Control • Ethernet Frame Ethernet8 Copyright 1998, John T. Gorgone, All Rights Reserved 8 CableCable DesignationsDesignations 10 BASE T SPEED TRANSMISSION MAX TYPE LENGTH Ethernet8 Copyright 1998, John T. -

LAB MANUAL for Computer Network

LAB MANUAL for Computer Network CSE-310 F Computer Network Lab L T P - - 3 Class Work : 25 Marks Exam : 25 MARKS Total : 50 Marks This course provides students with hands on training regarding the design, troubleshooting, modeling and evaluation of computer networks. In this course, students are going to experiment in a real test-bed networking environment, and learn about network design and troubleshooting topics and tools such as: network addressing, Address Resolution Protocol (ARP), basic troubleshooting tools (e.g. ping, ICMP), IP routing (e,g, RIP), route discovery (e.g. traceroute), TCP and UDP, IP fragmentation and many others. Student will also be introduced to the network modeling and simulation, and they will have the opportunity to build some simple networking models using the tool and perform simulations that will help them evaluate their design approaches and expected network performance. S.No Experiment 1 Study of different types of Network cables and Practically implement the cross-wired cable and straight through cable using clamping tool. 2 Study of Network Devices in Detail. 3 Study of network IP. 4 Connect the computers in Local Area Network. 5 Study of basic network command and Network configuration commands. 6 Configure a Network topology using packet tracer software. 7 Configure a Network topology using packet tracer software. 8 Configure a Network using Distance Vector Routing protocol. 9 Configure Network using Link State Vector Routing protocol. Hardware and Software Requirement Hardware Requirement RJ-45 connector, Climping Tool, Twisted pair Cable Software Requirement Command Prompt And Packet Tracer. EXPERIMENT-1 Aim: Study of different types of Network cables and Practically implement the cross-wired cable and straight through cable using clamping tool. -

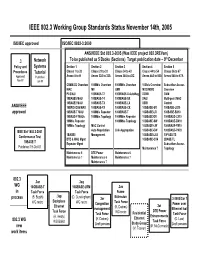

IEEE 802.3 Working Group Standards Status November 14Th, 2005

IEEE 802.3 Working Group Standards Status November 14th, 2005 ISO/IEC approved ISO/IEC 8802-3:2000 ANSI/IEEE Std 802.3-2005 (Was IEEE project 802.3REVam) th .3 Network To be published as 5 Books (Sections) Target publication date – 9 December Policy and Systems Section 1 Section 2 Section 3 Section 4 Section 5 Procedures Tutorial Clause 1 to 20 Clause 21 to 33 Clause 34 to 43 Clause 44 to 54 Clause 56 to 67 Approved Published Annex A to H Annex 22A to 32A Annex 36A to 43C Annex 44A to 50A Annex 58A to 67A Nov-97 Jun-95 CSMA/CD Overview 100Mb/s Overview 1000Mb/s Overview 10Gb/s Overview Subscriber Access MAC MII GMII MDC/MDIO Overview PLS/AUI 100BASE-T2 1000BASE-X AutoNeg XGMII OAM 10BASE5 MAU 100BASE-T4 1000BASE-SX XAUI Multi-point MAC 10BASE2 MAU 100BASE-TX 1000BASE-LX XSBI Control ANSI/IEEE 10BROAD36 MAU 100BASE-FX 1000BASE-CX 10GBASE-SR 100BASE-LX10 approved 10BASE-T MAU 100Mb/s Repeater 1000BASE-T 10GBASE-LR 100BASE-BX10 10BASE-F MAUs 100Mb/s Topology 1000Mb/s Repeater 10GBASE-ER 1000BASE-LX10 10Mb/s Repeater 1000Mb/s Topology 10GBASE-SW 1000BASE-BX10 10Mb/s Topology MAC Control 10GBASE-LW 1000BASE-PX10 IEEE Std 1802.3-2001 Auto Negotiation Link Aggregation 10GBASE-EW 1000BASE-PX20 Conformance Test 1BASE5 Management 10GBASE-LX4 10PASS-TS DTE & MAU Mgmt 10GBASE-CX4 2BASE-TL 10BASE-T Repeater Mgmt Subscriber Access Published 19-Oct-01 Maintenance 7 Topology Maintenance 6 DTE Power Maintenance 6 Maintenance 7 Maintenance 6 Maintenance 7 Maintenance 7 802.3 .3an .3aq WG 10GBASE-T 10GBASE-LRM .3as in Task Force Task Force Frame .3ap process (B.