Hogg Proofs, PAGES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prokofiev: Reflections on an Anniversary, and a Plea for a New

ИМТИ №16, 2017 Ключевые слова Прокофьев, критическое издание собрания сочинений, «Ромео и Джульетта», «Золушка», «Каменный цветок», «Вещи в себе», Восьмая соната для фортепиано, Янкелевич, Магритт, Кржижановский. Саймон Моррисон Прокофьев: размышления в связи с годовщиной и обоснование необходимости нового критического издания собрания сочинений Key Words Prokofiev, critical edition, Romeo and Juliet, Cinderella, The Stone Flower, Things in Themselves, Eighth Piano Sonata, Jankélévitch, Magritte, Krzhizhanovsky. Simon Morrison Prokofiev: Reflections on an Anniversary, And A Plea for a New Аннотация В настоящей статье рассматривается влияние цензуры на позднее Critical Edition советское творчество Прокофьева. В первой половине статьи речь идет об изменениях, которые Прокофьеву пришлось внести в свои балеты советского периода. Во второй половине я рассматриваю его малоизвестные, созданные еще до переезда в СССР «Вещи Abstract в себе» и показываю, какие общие выводы позволяют сделать This article looks at how censorship affected Prokofiev’s later Soviet эти две фортепианные пьесы относительно творческих уста- works and in certain instances concealed his creative intentions. In новок композитора. В этом контексте я обращаюсь также к его the first half I discuss the changes imposed on his three Soviet ballets; Восьмой фортепианной сонате. По моему убеждению, Прокофьев in the second half I consider his little-known, pre-Soviet Things in мыслил свою музыку как абстрактное, «чистое» искусство даже Themselves and what these two piano pieces reveal about his creative в тех случаях, когда связывал ее со словом и хореографией. Новое outlook in general. I also address his Eighth Piano Sonata in this критическое издание сочинений Прокофьева должно очистить context. Prokofiev, I argue, thought of his music as abstract, pure, even его творчество от наслоений, обусловленных цензурой, и выя- when he attached it to words and choreographies. -

The Musical Partnership of Sergei Prokofiev And

THE MUSICAL PARTNERSHIP OF SERGEI PROKOFIEV AND MSTISLAV ROSTROPOVICH A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC IN PERFORMANCE BY JIHYE KIM DR. PETER OPIE - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2011 Among twentieth-century composers, Sergei Prokofiev is widely considered to be one of the most popular and important figures. He wrote in a variety of genres, including opera, ballet, symphonies, concertos, solo piano, and chamber music. In his cello works, of which three are the most important, his partnership with the great Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was crucial. To understand their partnership, it is necessary to know their background information, including biographies, and to understand the political environment in which they lived. Sergei Prokofiev was born in Sontovka, (Ukraine) on April 23, 1891, and grew up in comfortable conditions. His father organized his general education in the natural sciences, and his mother gave him his early education in the arts. When he was four years old, his mother provided his first piano lessons and he began composition study as well. He studied theory, composition, instrumentation, and piano with Reinhold Glière, who was also a composer and pianist. Glière asked Prokofiev to compose short pieces made into the structure of a series.1 According to Glière’s suggestion, Prokofiev wrote a lot of short piano pieces, including five series each of 12 pieces (1902-1906). He also composed a symphony in G major for Glière. When he was twelve years old, he met Glazunov, who was a professor at the St. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR HARRY JOSEPH GILMORE Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: February 3, 2003 Copyright 2012 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in Pennsylvania Carnegie Institute of Technology (Carnegie Mellon University) University of Pittsburgh Indiana University Marriage Entered the Foreign Service in 1962 A,100 Course Ankara. Turkey/ 0otation Officer1Staff Aide 1962,1963 4upiter missiles Ambassador 0aymond Hare Ismet Inonu 4oint US Military Mission for Aid to Turkey (4USMAT) Turkish,US logistics Consul Elaine Smith Near East troubles Operations Cyprus US policy Embassy staff Consular issues Saudi isa laws Turkish,American Society Internal tra el State Department/ Foreign Ser ice Institute (FSI)7 Hungarian 1963,1968 9anguage training Budapest. Hungary/ Consular Officer 1968,1967 Cardinal Mindszenty 4anos Kadar regime 1 So iet Union presence 0elations Ambassador Martin Hillenbrand Israel Economy 9iberalization Arab,Israel 1967 War Anti,US demonstrations Go ernment restrictions Sur eillance and intimidation En ironment Contacts with Hungarians Communism Visa cases (pro ocations) Social Security recipients Austria1Hungary relations Hungary relations with neighbors 0eligion So iet Mindszenty concerns Dr. Ann 9askaris Elin OAShaughnessy State Department/ So iet and Eastern Europe EBchange Staff 1967,1969 Hungarian and Czech accounts Operations Scientists and Scholars eBchange programs Effects of Prague Spring 0elations -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

1 Program Notes MONTANA CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY

Program Notes MONTANA CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY October 30, 2015, 7:30pm Reynolds Recital Hall, MSU Bozeman, 7:30pm MUIR STRING QUARTET Peter Zazofsky, violin Lucia Lin, violin Steven Ansell, viola Michael Reynolds, cello with guest Michele Levin, piano Quartet for Strings in C Minor, Quartettsatz, D. 703 (1820) FRANZ SCHUBERT [1797-1828] [Duration: ca. 10 minutes] "Picture to yourself," he wrote to a friend at this time, "a man whose health can never be reestablished, who from sheer despair makes matters worse instead of better; picture to yourself, I say, a man whose most brilliant hopes have come to nothing, to whom proffered love and friendship are but anguish, whose enthusiasm for the beautiful — an inspired feeling, at least— threatens to vanquish entirely; and then ask yourself if such a condition does not represent a miserable and unhappy man.... Each night, when I go to sleep, I hope never again to waken, and every morning reopens the wounds of yesterday." [Schubert, 1819] Schubert was extremely self-critical, leaving an unusually large number of incomplete works behind. The most celebrated is the Unfinished Symphony, however, many fragments survive of abandoned string quartets. Among these is the Quartettsatz ("Quartet Movement"), written just before Schubert turned 24, the only one to have entered the standard repertoire. When Brahms was working on the first scholarly edition of Schubert's music, he found, in the manuscript score of the Quartettsatz, the sketch (about 40 measures) for a second movement Andante in A-flat; apparently Schubert intended to write a four-movement work, though this movement is independently convincing and complete. -

(With) Shakespeare (/783437/Show) (Pdf) Elizabeth (/783437/Pdf) Klett

11/19/2019 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation ISSN 1554-6985 V O L U M E X · N U M B E R 2 (/current) S P R I N G 2 0 1 7 (/previous) S h a k e s p e a r e a n d D a n c e E D I T E D B Y (/about) E l i z a b e t h K l e t t (/archive) C O N T E N T S Introduction: Dancing (With) Shakespeare (/783437/show) (pdf) Elizabeth (/783437/pdf) Klett "We'll measure them a measure, and be gone": Renaissance Dance Emily Practices and Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (/783478/show) (pdf) Winerock (/783478/pdf) Creation Myths: Inspiration, Collaboration, and the Genesis of Amy Romeo and Juliet (/783458/show) (pdf) (/783458/pdf) Rodgers "A hall, a hall! Give room, and foot it, girls": Realizing the Dance Linda Scene in Romeo and Juliet on Film (/783440/show) (pdf) McJannet (/783440/pdf) Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet: Some Consequences of the “Happy Nona Ending” (/783442/show) (pdf) (/783442/pdf) Monahin Scotch Jig or Rope Dance? Choreographic Dramaturgy and Much Emma Ado About Nothing (/783439/show) (pdf) (/783439/pdf) Atwood A "Merry War": Synetic's Much Ado About Nothing and American Sheila T. Post-war Iconography (/783480/show) (pdf) (/783480/pdf) Cavanagh "Light your Cigarette with my Heart's Fire, My Love": Raunchy Madhavi Dances and a Golden-hearted Prostitute in Bhardwaj's Omkara Biswas (2006) (/783482/show) (pdf) (/783482/pdf) www.borrowers.uga.edu/7165/toc 1/2 11/19/2019 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation The Concord of This Discord: Adapting the Late Romances for Elizabeth the -

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys. -

Steve Reich at 80: a Princeton Celebration

princeton.edu/music Monday, March 20, 2017 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Dasha Koltunyuk, [email protected], 609-258-6024 STEVE REICH AT 80: A PRINCETON CELEBRATION FEATURING A FREE PANEL DISCUSSION AND CONCERT BY SŌ PERCUSSION & GUESTS Sō Percussion, Princeton University’s Edward T. Cone Artists-in-Residence, will host a celebration—free and open to all—of iconic American composer Steve Reich on Tuesday, March 14, 2017 at Richardson Auditorium in Alexander Hall. The festivities will commence with a panel discussion at 4PM on Reich and his legacy, featuring conductor David Robertson, composer Julia Wolfe, and cellist Maya Beiser in conversation with musicology Professor Simon Morrison, and a second panel discussion at 5PM with Professor Morrison, composition Professor Donnacha Dennehy and Professor Steven Mackey in conversation with percussionist Adam Sliwinski of Sō Percussion. A mini-marathon concert, entitled Six Decades of Reich, will follow at 7:30PM, sampling works from each decade of the composer’s prolific career. Sō Percussion will be joined onstage by vocalist Beth Meyers, soprano Daisy Press, flutist Jessica Schmitz, pianists Orli Shaham and Corey Smythe, and cellist Maya Beiser. Ms. Beiser will perform Cello Counterpoint, written for her in 2003. The concert will culminate with Reich’s breakthrough masterpiece, Drumming, which Sō Percussion had performed at the Lincoln Center Festival this past fall to critical acclaim. Though admission for both the discussion and the concert are free, reservations are required for the concert. Please visit tickets.princeton.edu, or call the Frist Center Box Office at 609-258- 9220. “To hear [Sō Percussion], with their clarity and vivacity, in Mr. -

Behind the Scenes of the Fiery Angel: Prokofiev's Character

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ASU Digital Repository Behind the Scenes of The Fiery Angel: Prokofiev's Character Reflected in the Opera by Vanja Nikolovski A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved March 2018 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Brian DeMaris, Chair Jason Caslor James DeMars Dale Dreyfoos ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2018 ABSTRACT It wasn’t long after the Chicago Opera Company postponed staging The Love for Three Oranges in December of 1919 that Prokofiev decided to create The Fiery Angel. In November of the same year he was reading Valery Bryusov’s novel, “The Fiery Angel.” At the same time he was establishing a closer relationship with his future wife, Lina Codina. For various reasons the composition of The Fiery Angel endured over many years. In April of 1920 at the Metropolitan Opera, none of his three operas - The Gambler, The Love for Three Oranges, and The Fiery Angel - were accepted for staging. He received no additional support from his colleagues Sergi Diaghilev, Igor Stravinsky, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Pierre Souvchinsky, who did not care for the subject of Bryusov’s plot. Despite his unsuccessful attempts to have the work premiered, he continued working and moved from the U.S. to Europe, where he continued to compose, finishing the first edition of The Fiery Angel. He married Lina Codina in 1923. Several years later, while posing for portrait artist Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva, the composer learned about the mysteries of a love triangle between Bryusov, Andrey Bely and Nina Petrovskaya. -

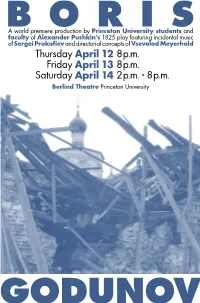

Program for the Production

BORISA world premiere production by Princeton University students and faculty of Alexander Pushkin’s 1825 play featuring incidental music of Sergei Prokofiev and directorial concepts of Vsevolod Meyerhold Thursday April 12 8 p.m. Friday April 13 8 p.m. Saturday April 14 2 p.m. † 8 p.m. Berlind Theatre Princeton University GODUNOV Sponsored by funding from Peter B. Lewis ’55 for the University Center for the Creative and Performing Arts with the Department of Music † Council of the Humanities † Edward T. Cone ’39 *43 Fund in the Humanities † Edward T. Cone ’39 *43 Fund in the Arts † Office of the Dean of the Faculty † Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures † School of Architecture † Program in Theater and Dance † Friends of the Princeton University Library and the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections † Alumni Council † Program in Russian and Eurasian Studies BORIS Simon Morrison † Caryl Emerson project managers Tim Vasen stage director Rebecca Lazier choreographer Michael Pratt † Richard Tang Yuk conductors Jesse Reiser † Students of the School of Architecture set designers Catherine Cann costume designer Matthew Frey lighting designer Michael Cadden dramaturg Peter Westergaard additional music Antony Wood translator Darryl Waskow technical coordinator Rory Kress Weisbord ’07 assistant director William Ellerbe ’08 assistant dramaturg Ilana Lucas ’07 assistant dramaturg Students of the Princeton University Program in Theater and Dance, Glee Club, and Orchestra GODUNOV Foreword I’m delighted to have the opportunity to welcome you to this performance of what has been, until now, a lost work of art, one now made manifest through a series of remarkable collaborations. -

Contents Price Code an Introduction to Chandos

CONTENTS AN INTRODUCTION TO CHANDOS RECORDS An Introduction to Chandos Records ... ...2 Harpsichord ... ......................................................... .269 A-Z CD listing by composer ... .5 Guitar ... ..........................................................................271 Chandos Records was founded in 1979 and quickly established itself as one of the world’s leading independent classical labels. The company records all over Collections: Woodwind ... ............................................................ .273 the world and markets its recordings from offices and studios in Colchester, Military ... ...208 Violin ... ...........................................................................277 England. It is distributed worldwide to over forty countries as well as online from Brass ... ..212 Christmas... ........................................................ ..279 its own website and other online suppliers. Concert Band... ..229 Light Music... ..................................................... ...281 Opera in English ... ...231 Various Popular Light... ......................................... ..283 The company has championed rare and neglected repertoire, filling in many Orchestral ... .239 Compilations ... ...................................................... ...287 gaps in the record catalogues. Initially focussing on British composers (Alwyn, Bax, Bliss, Dyson, Moeran, Rubbra et al.), it subsequently embraced a much Chamber ... ...245 Conductor Index ... ............................................... .296 -

Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Prokofiev Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev (/prɵˈkɒfiɛv/; Russian: Сергей Сергеевич Прокофьев, tr. Sergej Sergeevič Prokof'ev; April 27, 1891 [O.S. 15 April];– March 5, 1953) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor. As the creator of acknowledged masterpieces across numerous musical genres, he is regarded as one of the major composers of the 20th century. His works include such widely heard works as the March from The Love for Three Oranges, the suite Lieutenant Kijé, the ballet Romeo and Juliet – from which "Dance of the Knights" is taken – and Peter and the Wolf. Of the established forms and genres in which he worked, he created – excluding juvenilia – seven completed operas, seven symphonies, eight ballets, five piano concertos, two violin concertos, a cello concerto, and nine completed piano sonatas. A graduate of the St Petersburg Conservatory, Prokofiev initially made his name as an iconoclastic composer-pianist, achieving notoriety with a series of ferociously dissonant and virtuosic works for his instrument, including his first two piano concertos. In 1915 Prokofiev made a decisive break from the standard composer-pianist category with his orchestral Scythian Suite, compiled from music originally composed for a ballet commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes. Diaghilev commissioned three further ballets from Prokofiev – Chout, Le pas d'acier and The Prodigal Son – which at the time of their original production all caused a sensation among both critics and colleagues. Prokofiev's greatest interest, however, was opera, and he composed several works in that genre, including The Gambler and The Fiery Angel. Prokofiev's one operatic success during his lifetime was The Love for Three Oranges, composed for the Chicago Opera and subsequently performed over the following decade in Europe and Russia.