Informal Learning Culture Through the Life Course: Initiatives in Native Organizations and Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Casino Rama Split Goes to Mediation

Volume 17 Issue 1 Published monthly by the Union of Ontario Indians - Anishinabek Nation Single Copy: $2.00 Jan-Feb 2005 IN THE Bill would create revenue-sharing framework SAULT STE. MARIE (CP) — Native leaders say the bill would territories.” mittee stage. That the Liberal gov- NEWS The head of the Assembly of First give bands a framework to secure As employers go looking for ernment has allowed the bill to get Nations is applauding an Ontario revenue-sharing agreements with labour and the country faces a short- that far is “momentous,” said Premier’s slurs private-member’s bill that would players in industries such as forestry, age of skilled workers, aboriginal Bisson. FREDERICTON (CP) – help Natives get a share of the mining and even tourism. communities need to be able to “The reason I think they allowed The latest round of insults in money made from natural resources Efforts like these are part of revi- establish appropriate training sys- it to happen is the government gen- New Brunswick’s legislature on their traditional lands. talizing First Nations economies so tems to fill those positions, Fontaine uinely wants, I think, to measure the has prompted a request from The bill, put forward by provin- that they can provide workers to said. response of the public,” said the the Speaker of the House for cial NDP native affairs critic Gilles benefit the general economy, said “You look at (First Nations) MPP for Timmins-James Bay. more respect. Speaker Bev Bisson, aims to create an equitable Phil Fontaine, National Chief of the unemployment rates at 40 to 90 per When the legislature resumes on Harrison met with Premier way for First Nations in northern Assembly of First Nations. -

How to Apply

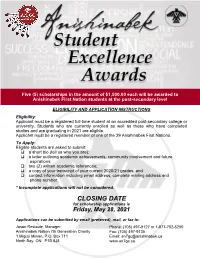

Five (5) scholarships in the amount of $1,500.00 each will be awarded to Anishinabek First Nation students at the post-secondary level ELIGIBILITY AND APPLICATION INSTRUCTIONS Eligibility: Applicant must be a registered full-time student at an accredited post-secondary college or university. Students who are currently enrolled as well as those who have completed studies and are graduating in 2021 are eligible. Applicant must be a registered member of one of the 39 Anishinabek First Nations. To Apply: Eligible students are asked to submit: a short bio (tell us who you are); a letter outlining academic achievements, community involvement and future aspirations; two (2) written academic references; a copy of your transcript of your current 2020/21 grades; and contact information including email address, complete mailing address and phone number. * Incomplete applications will not be considered. CLOSING DATE for scholarship applications is Friday, May 28, 2021 Applications can be submitted by email (preferred), mail, or fax to: Jason Restoule, Manager Phone: (705) 497-9127 or 1-877-702-5200 Anishinabek Nation 7th Generation Charity Fax: (705) 497-9135 1 Migizii Miikan, P.O. Box 711 Email: [email protected] North Bay, ON P1B 8J8 www.an7gc.ca Post-secondary students registered with the following Anishinabek First Nation communities are eligible to apply Aamjiwnaang First Nation Moose Deer Point Alderville First Nation Munsee-Delaware Nation Atikameksheng Anishnawbek Namaygoosisagagun First Nation Aundeck Omni Kaning Nipissing First Nation -

December 2011

Page 1 Volume 23 Issue 10 Published monthly by the Union of Ontario Indians - Anishinabek Nation Single Copy: $2.00 DECEMBER 2011 M’Chigeeng First Nation Chief Joseph Hare moves to accept the Anishinaabe Chi-Naaknigewin, in principle. Chief Shining Turtle of Whitefish River, seated left, seconded the motion. Both Chiefs spoke eloquently on the need to move ahead collectively and to trust one another. The vote was unanimous. Chiefs unanimous on constitution By Mary Laronde on our terms, of our rights as an in- lieve in the work done by the com- on the articles of the constitution, Government will operate. GARDEN RIVER FN–The An- digenous people. It tells our people mittee and the Elders. It is time to deferred its adoption to allow fur- Individual First Nation discus- ishinaabe Chi-Naaknigewin was that we will determine our future. believe in and trust each other.” ther discussion within First Nation sion on the revised Anishinaabe accepted in principle by a unani- It should inspire us and raise our Seconder of the motion, Chief communities. The Chiefs issued Chi-Naaknigewin will continue mous decision of the Chiefs at the confidence to do what we need Shining Turtle of Whitefish River, a new mandate and the Ngo Dwe until March 1, 2012, at which time November 15 and 16 Fall Assem- to do to for ourselves -- establish added, “This is the very best work Waangizid Anishinaabe Steering input will be analyzed, any revi- bly at Garden River, a step that our governments, implement our our citizens came up with, not the Committee was established to ad- sions made, and a final revised ver- bodes well for the official adoption treaties, and exercise our inherent government (Canada). -

Anishinabek Nation Governance Agreement at a Glance

The Anishinabek Nation Governance Agreement At a Glance ANISHINABEK NATION GOVERNANCE AGREEMENT OVERVIEW For more than 25 years, the Anishinabek Nation and the Government of Canada have been negotiating the proposed Anishinabek Nation Governance Agreement that will recognize, not create, the Anishinabek First Nations’ law-making powers and authority to self-govern, thus removing them from the governance provisions of the Indian Act. The First Nations that ratify the proposed Anishinabek Nation Governance Agreement (Participating First Nations) will have the power to enact laws in the following areas: leadership selection, citizenship, language and culture, and operation of government. The proposed Anishinabek Nation Governance Agreement includes the complementary Anishinabek Nation Fiscal Agreement that outlines the funding for governance-related functions. ANISHINABEK NATION GOVERNANCE AGREEMENT ROAD MAP 2007 2019 2020 The Anishinabek Nation Negotiations on the Additional Anishinabek and Canada reached a 2011 Anishinabek Nation Nation member First non-binding Agreement- Declaration of the Ngo Governance Agreement Nations to vote in May 1-30 in-Principle Dwe Waangizid conclude Anishinaabe (One Anishinaabe Family) 2009 Anishinabek Nation 2012 1995 E’Dbendaagzijig Proclamation Anishinabek Nation Naaknigewin (Citizenship of Anishinaabe 2020 2021 Chiefs-in-Assembly give Law) is approved Chi-Naaknigewin mandate to restore Anishinabek Nation Proposed jurisdiction with focus on member First Nations Effective Date: governance and education to -

Lake Huron First Nations Robinson Huron Treaty (1854) Territory

Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre Algoma Unviersity Lake Huron First Nations Robinson Huron Treaty (1854) Territory Photo Album Display Purposes Only – Do Not Remove Introduction This photo album has been compiled by the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre. The Centre developed out of the work undertaken by the Shingwauk Project. The Project began in 1979 as a cross-cultural research and educational development project of Algoma University (AU) and the Children of Shingwauk Alumni Association (CSAA). The Shingwauk Project and the CSAA have undertaken many activities since 1979 including reunions, healing circles, publications, videos, photo displays, curriculum development and the establishment of an archive, library and heritage collections, as well as a Shingwauk Directory and website. Over many years and in many ways these initiatives have been generously supported by Indigenous and non-Indigenous governments, churches, non-governmental organizations and private individuals. The desire of the Shingwauk Project to promote sharing, healing, and learning continues today through the work of the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre. 2 Conditions of Use and Acknowledgements This publication is for research purposes only. The information and photographs contained herein are constantly being updated and revised. If you have additional information or photographs that you would like to add to the collection, please do not hesitate to contact us. We would like to thank the Children of Shingwauk Alumni Association, Algoma University, the Aboriginal -

31 Appeal Decision Overturned Ken Ward's Ongoing Column About Living with by Rob Mckinley Appeal Threw out a 1995 Judge- a Constitutional Challenge

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA B DI o had Ar hives Canada III I II WHAT'S INSIDE 7 QUOTABLE QUOTE "Mr. Irwin has done a lot to change the face of Indian Affairs and Northern Develop- ment over the last speakér three -and -a -half years. It's not like we're starting from a July 1997 Canada's National Aboriginal News Source Volume I5 No. 3 standstill with the recommendations of Bearwalker defence RCAP. It is a beacon for the future and I successful at trial view it that way." By David Stapleton prove beyond a reasonable doubt - New Indian Windspeaker Contributor that Thompson was not the ag- Affairs Minister gressor. GORE BAY, Ont. "I accept the evidence on Na- Jane Stewart. tive spirituality as being a sin- In a precedent for Canada's jus- cerely held belief," said Trainor. a Manitoulin Island, ManyAboriginal beliefs would tice system, A WALLOP Ont. man stands acquitted of a be foreign to some Canadians, he PACKING manslaughter charge based on added. his belief he defended himself Trainor indicated he accepted Windspeaker had so from a bearwalker. Jacko's belief in bearwalkers be- much news to share with Leon Jacko, 21, of cause Thompson had been learn- Gavin its readers we had a dif- Sheguiandah First Nation was ing traditional Aboriginal medi- charged with the 1995 slaying of cines and witchcraft, and had ficult time fitting all of his great -uncle Ronald Wilfred boasted of having bearwalker this information into just Thompson, 45, also of power. one issue. Sheguiandah. Justice Richard Jacko was charged after Trainor of Ontario's general di- Thompson's half- naked, battered vision court ruled on May 29 in body was found the evening of Check out our stories Gore Bay that Jacko's slaying of June 30, 1995 face down in a on: Thompson was not an act of ag- blood -spattered clearing outside gression, but self-defense to pro- a truck camper behind Jacko's tect himself and others from the house. -

May 2013 ANISHINABEK NEWS the Voice of the Anishinabek Nation

Page 1 Anishinabek News May 2013 ANISHINABEK NEWS The voice of the Anishinabek Nation Volume 25 Issue 4 Published monthly by the Union of Ontario Indians - Anishinabek Nation Single Copy: $2.00 May 2013 OUR TIME IS NOW: Madahbee UOI Offi ces –This year marks the resentative of the Crown back then, governments that we don’t need in April, 2014. 250th anniversary of The Royal there was no doubt that we were ca- them to tell us how to look after our Madahbee pointed to the recent Proclamation, a landmark document pable of managing our own affairs, citizens.” stream of Harper government legis- by which the British Crown recog- governing our own communities – A key agenda item at the June lation that ignores First Nations ju- nized the nationhood of “the Indian the British representatives were well 3-6 assembly in Munsee-Delaware risdiction on everything from First tribes of North America.” aware of our ability to assert our ju- will be the future of the Anishinabek Nations election processes to matri- Commemoration of the 1763 risdiction because, when push came Education System, which is intend- monial real property rights. event is an agenda item for June’s to shove, First Nation warriors dev- ed to restore jurisdiction for educa- “We need to start occupying the annual general assembly of An- astated nine of eleven British Forts tion of some 2500 K-12 Anishina- fi eld in these areas – we’ve got to get doyouknowyourrights.ca ishinabek Nation chiefs, and Grand in Pontiac’s War. bek Nation students. Half a day on moving on some of these issues. -

Waubetek News 2019

Waubetek Business Development Corporation “A Community Futures Development Corporation” WAUBETEK NEWS 2019 Featured Businesses this Issue INSIDE THIS ISSUE ➢ Northern Integrated Commercial Fisheries Initiative ..............pg.2 ➢Burke Stonework and Excavation - Bringing Your Landscape Dreams to Life……………………………………………….pg 3 ➢ M’Chigeeng Freshmart Store…………………………….....pg 4 ➢ Twiggs Coffee Roasters – More than just Coffee………........pg 5 ➢“Picking up Where Mother Nature Leafs Off.”…………………………….…………………….…......pg 6 ➢ WAUBETEK NEWS BRIEFS….. …………………..………pg 7 ➢ Outreach Services Spring 2019………………………....……pg 8 ➢ Touched By The Entrepreneurial Spirit....................................pg 9 ➢ Touched by the Entrepreneurial Spirit Map Guide………....pg 10 ➢ Waubetek Student Bursary Recipients………………..….....pg 11 ➢ Investing in the Aboriginal Business Spirit……………….. .pg 12 ➢ 30 years of Investing and more …………………………….pg 13 Freshly Roasted. Fair Trade. Organic. Waubetek News – Spring 2019 www.waubetek.com 2 New Program - Northern Integrated Commercial Fisheries Initiative In April, 2019, the Northern Integrated Commercial Fisheries working capital and scientific studies is not available through Initiative (NICFI) will formally launch as Canada’s newest NICFI, however. commercial fishing and aquaculture-related program. The Interest in the program was quite intense in late 2018 but aspect of this initiative dealing with commercial fisheries will Waubetek was able to gather funds for a program “soft launch” be delivered by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the in order to support nine projects. These ranged from Waubetek Business Development Corporation will be assistance with equipment and infrastructure, expansion of supporting aquaculture developments. NICFI was created to existing operations, feasibility studies, detailed designs, assist Indigenous groups develop commercial fishing and community engagements, business plans, partnership aquaculture operations that will: be economically self- development, and travel for facility visits. -

Sustaining the Future of Our Nations”

“Sustaining the Future of our Nations” A Tool Kit for Action This tool kit is funded by the Ontario Trillium Foundation and prepared by Chiefs of Ontario Ontario First Nations Young Peoples Council Youth Council Development Tool Kit COPYRIGHT Rights Reserved. This document including the OFNYPC logo is copyright Chiefs of Ontario 2007. It may not be reproduced or transmitted without the permission from the Chiefs of Ontario. CONTACT INFORMATION Chiefs of Ontario Political Office Youth Coordinator Phone: (807) 626-9339 Fax: (807) 626-9404 Email: [email protected] Administrative Office 111 Peter Street, Suit 804 Toronto, ON M5V 2H1 Phone: (416) 597-1266 Fax: (416)597-8365 Toll Free: 1-877-517-6527 www.chiefs-of-ontario.org CREDITS Logo Design: Albert Pechawis Photos: Bruno Henry THE WRITING Laura Calm Wind, the Youth Coordinator for Chiefs of Ontario completed the writing of this toolkit. FINANCIAL SUPPORT Thank you to the Ontario Trillium Foundation for funding the development and printing of this toolkit. “Sustaining the Future of our Nations” 2 Ontario First Nations Young Peoples Council Youth Council Development Tool Kit TABLE OF CONTENTS GREETINGS SECTION 1 - INTRODUCTION Preamble Introduction to the Toolkit Purpose of the Toolkit Scope of the Toolkit SECTION 2 - ONTARIO FIRST NATIONS YOUNG PEOPLES COUNCIL Background Chiefs of Ontario Organizational Objectives Organizational Structure Key Activities Logo Mandate Introduction to the Regional Youth Council Purpose of the Council Members of the Ontario First Nations Young Peoples Council Terms -

The Manitoulin Phragmites Project Results of 2019 Work Compiled by Judith Jones, Project Coordinator, October 2019

The Manitoulin Phragmites Project Results of 2019 Work compiled by Judith Jones, Project Coordinator, October 2019 Volunteers and Phrag Project team controlling Phragmites at Mud Bay, Cockburn Island Phragmites (“frag-MITE-eeze”) is a hugely tall, European grass that has been spreading aggressively on shorelines and in wetlands in our area. Phragmites can quickly grow into dense patches which eventually wipe out all other vegetation. It is a serious threat to property values, recreation, tourism, biodiversity, and aesthetics. Southern Ontario has lost hectares and hectares of beaches and other natural habitat to Phragmites. The Manitoulin Phragmites Project was started to make sure this does not happen here! We have just finished our 4th season of work on Manitoulin, Cockburn, and Great Duck Islands. You are receiving this letter because there is Phragmites on your property or in your jurisdiction, or because you have been involved with the project. We want you to know where the Phragmites is or was (page 4), what has been done, and how the results turned out. We also want to talk about the future to ensure we maintain what has been achieved. The work of the Project has been EXTREMELY SUCCESSFUL! You can see some striking before and after photos on our Facebook page: Manitoulin Phragmites Project. On Manitoulin Island, all of the Lake Huron shore from South Baymouth to the Mississaugi Lighthouse is completely clear of Phragmites except the mouth of Blue Jay Creek and the bay east of Burnt Island. On Cockburn Island and Great Duck Island, all sand dune habitat is now clear of Phrag. -

Master Education Agreement (2017)

ö AN/ON Draft March 29,2017 MASÏER EDUCATION AG REEMENT.. ;'1, BETWÉEN: 'r,,jiij ,..:,, . .;. .lti :ijt:¡.,,. ;:,,;r11,'::: i' TþIE ANISHINABEK FIRST '(the''nAnishinabek First -AND- i', I ::l l'; t.: t '). , ¡: THE KINO TION BODY, . .i .,. .. .:: ',. (the "KEBll) '- r . t 1 , :- - ,r , i..,:i i l. :.; , .. I .. ,t., ..t, ,1. , ..,, ,t by. .t \j . ) "Parties') " Page 1 of45 I AN/ON Draft March 29,2017 Table of Gontents Part 1 : Definitions and lnterpretation ......... 5 Definitions .............. 5 6 Part 2: Shared Vision .¡¡..¡....¡.¡..r 7 Part 3: Objectives P art 4= Princi ples of the Relationshi p........... I Part 5: The E I :,1,: The Anishi 9 The First Nations 9 Regional Education Councils 10 The Kinoomaadziwin Education Body ........... I I The Provinçially.-Fnnded ¡r¡¡,t,,¡..r.¡.¡¡...,.....,........ I 4 Roles and Responsibilities of Boards. Part 6: Relationship Between the 16 How the Parties Will with 16 Connections h¡ cation and the Provincially- Fun.ded "'.'?i:i:: Joint Master ;t..,.i.'.;,;:.r... ; ii......; ¡,ri.......................... I 6 ParlT: 18 nd Transi(ions ..,.,,, ¡,,.t.r.¡.¡,. ¡¡ ¡i.. :.................,.......,.. 1 8 20 21 Culture a 21 Curriculum D ent 22 Professional and Leadershi p Development 23 Enhanced Engagement and Relationships 23 Anishinabek Education System and School Board Relationships 24 Granting of Diploma .............. 26 Part 8: Data and lnformation Sharing 27 Page 2 of 45 , AN/ON Draft March 29;2017 Part 9: Research ...¡..,¡¡i..r.¡.,........i....:.t.......28 'Research by the Parties.... Third Party Research..,r.¡..¡..,i... Fart 10: lmplementation and. Evaluation of this:Agreer-nênt..i;r;......¡:,.¡¡';¡;;;;.....:..;.;.;29 'Part 1.1: Targeted lnitiatives and,lnvestrnents .i.:;r:.:.,..'..i;.i...:¡...ii...;..;..,..à..i....,.......,..,,. -

First Nations Will Share Larger Slice of Gaming

Volume 18 Issue 3 Published monthly by the Union of Ontario Indians - Anishinabek Nation Single Copy: $2.00 April 2006 IN THE Fontaine NEWS observes Indian school boards? CALGARY (CP) – Indian Af- serious fairs minister Jim Prentice says he wants to create aboriginal school boards in Alberta – a ‘fl aw’ change he contends will help students. They would include OTTAWA – National Chief Phil representatives who were Fontaine says there is a “signifi cant elected and made accountable fl aw” in the so-called “Account- for their decisions. ability Act” introduced by Stephen New water rules Harper’s new Conservative govern- OTTAWA (CP) – Indian Af- ment. fairs Minister Jim Prentice has Since only 17 of 633 First Na- announced new standards and tions across Canada have full self- clean-up plans – but no extra government agreements, the As- cash – to help First Nations at sembly of First Nations leader says risk from dirty water. He said, the new legislation has the effect of 170 of 755 water treatment singling out almost all First Nation systems pose health hazards governments for unnecessary scru- due to lack of training, mainte- tiny of their fi nancial management. nance and standards. “Provincial and municipal gov- Butt-out day May 31 ernments that receive cash transfers Smoking is the primary cause from the government of Canada will of premature, avoidable death not be subject to the same scrutiny and disease in Ontario, respon- from the Auditor General under the sible for 16,000 deaths each proposed legislation,” Fontain said, Ontario Regional Chief Angus Toulouse, Sagamok Anishnawbek FN, and Ontario Premier Dalton McGuinty year.