KON SATOSHI and JAPAN's MONSTERS in the CITY Chris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kon Satoshi E Morimoto Kōji

Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue, Economie e Istituzioni dell’Asia e dell’Africa Mediterranea ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004 Tesi di Laurea Magistrale Oltre i limiti della realtà: Kon Satoshi e Morimoto Kōji Relatore Ch. Prof. Maria Roberta Novielli Correlatore Ch. Prof. Davide Giurlando Laureando Maura Valentini Matricola 841221 Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 要旨 数年前、私は『妄想代理人』というアニメを見たことがある。その作品はあのとき見てい たアニメに全く異なるもので、私を非常に驚かせた。一見普通のように見える探偵物語は次第 に奇妙な展開になり、私はその魅力に引き込まれた。当時の私はそのアニメの監督をまだ知ら なかったが、「このような作品を考え出すことができる人は素晴らしい映画人と言っても過言では ない」と思ったことをはっきり覚えている。小さい頃から新しい視線で見た現実について語る物語 に興味があった。故に、私の卒業論文を夢、思い出、シュールレアリスムなどを使って違った現実 を語る幻視的芸術家の今敏と森本晃司について書くことに決めた。 今敏と森本晃司はお互いに何の関係もないと考えられる。前者はマッドハウスと協力し て海外でも有名な映画をつくり、後者は多岐にわたる才能を持つ芸術家で、主に短編映画で 知られている。しかし、よく見ると二人には多くの共通点がある。この論文の目的は今と森本の 作品を基にして二人の共通点を解説するということである。 はじめに、二人の社会文化的影響を示すために、歴史的背景と監督たちの経歴を短 く説明する。次に、二人が協力して作った『Magnetic Rose』という映画を分析して、二人の主 な特徴を見つける。その特徴は限界がない特別な現実観、テクノロジーの魅力、そして音楽や 比喩を使って表した物の意味が深まることである。最後に今と森本のさまざまな作品を分析し、 二人の特徴を見つけて、検討する。 この研究は私の情熱から生まれたものであり、この論文を読んで今敏や森本晃司の作 品に興味を持つ人が増えることを願う。 INDICE INTRODUZIONE .............................................................................................. 3 CAPITOLO 1. CONTESTO STORICO E SOCIO-CULTURALE.............................................. 5 1.1. Shinjinrui: la “nuova razza”................................................................................................. 5 1.2. I mondi incantati dello Studio Ghibli ................................................................................... 7 1.3. Visioni post-apocalittiche -

Sailor Mars Meet Maroku

sailor mars meet maroku By GIRNESS Submitted: August 11, 2005 Updated: August 11, 2005 sailor mars and maroku meet during a battle then fall in love they start to go futher and futher into their relationship boy will sango be mad when she comes back =:) hope you like it Provided by Fanart Central. http://www.fanart-central.net/stories/user/GIRNESS/18890/sailor-mars-meet-maroku Chapter 1 - sango leaves 2 Chapter 2 - sango leaves 15 1 - sango leaves Fanart Central A.whitelink { COLOR: #0000ff}A.whitelink:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.whitelink:visited { COLOR: #0000ff}A.BoxTitleLink { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:hover { COLOR: #465584; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:visited { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.normal { COLOR: blue}A.normal:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.normal:visited { COLOR: #000020}A { COLOR: #0000dd}A:hover { COLOR: #cc0000}A:visited { COLOR: #000020}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper { COLOR: #ff0000}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:hover { COLOR: #ffaaaa}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:visited { COLOR: #cc0000}.BoxTitleColor { COLOR: #000000} picture name Description Keywords All Anime/Manga (0)Books (258)Cartoons (428)Comics (555)Fantasy (474)Furries (0)Games (64)Misc (176)Movies (435)Original (0)Paintings (197)Real People (752)Tutorials (0)TV (169) Add Story Title: Description: Keywords: Category: Anime/Manga +.hack // Legend of Twilight's Bracelet +Aura +Balmung +Crossovers +Hotaru +Komiyan III +Mireille +Original .hack Characters +Reina +Reki +Shugo +.hack // Sign +Mimiru -

Elements of Realism in Japanese Animation Thesis Presented In

Elements of Realism in Japanese Animation Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By George Andrew Stey Graduate Program in East Asian Studies The Ohio State University 2009 Thesis Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance, Advisor Professor Maureen Hildegarde Donovan Professor Philip C. Brown Copyright by George Andrew Stey 2009 Abstract Certain works of Japanese animation appear to strive to approach reality, showing elements of realism in the visuals as well as the narrative, yet theories of film realism have not often been applied to animation. The goal of this thesis is to systematically isolate the various elements of realism in Japanese animation. This is pursued by focusing on the effect that film produces on the viewer and employing Roland Barthes‟ theory of the reality effect, which gives the viewer the sense of mimicking the surface appearance of the world, and Michel Foucault‟s theory of the truth effect, which is produced when filmic representations agree with the viewer‟s conception of the real world. Three directors‟ works are analyzed using this methodology: Kon Satoshi, Oshii Mamoru, and Miyazaki Hayao. It is argued based on the analysis of these directors‟ works in this study that reality effects arise in the visuals of films, and truth effects emerge from the narratives. Furthermore, the results show detailed settings to be a reality effect common to all the directors, and the portrayal of real-world problems and issues to be a truth effect shared among all. As such, the results suggest that these are common elements of realism found in the art of Japanese animation. -

Voice Actor) Next Month Some Reviews, Pictures from ICFA and Wendee Lee (Faye, Cowboy Bebop) Maybe from Some Other Events

Volume 24 Number 10 Issue 292 March 2012 Events A WORD FROM THE EDITOR Megacon was fun but tiring. I got see some people I Knighttrokon really respect and admire. It felt bigger than last year. I heard March 3 from the Slacker and the Man podcast that the long lines from University of Central Florida Student Union previous Megacons were not there this year. Checkout the report $5 per person in this issue. Guests: Kyle Hebert (voice actor) Next month some reviews, pictures from ICFA and Wendee Lee (Faye, Cowboy Bebop) maybe from some other events. knightrokon.com Sun Coast: CGA show (gaming and comics) March 31 Tampa Bay Comic Con Charlotte Harbor Event and Conference Center March 3-4 75 Taylor Street Double Tree Hotel Punta Gorda, Florida 33950 4500 West Cypress Street $8 or $6 with a can of food per person Tampa, FL 33607 $15 per day ICFA 33 (professional conference) Guests: Jim Steranko (comic writer and artist) March 21-25 Mike Grell(comic writer and artist) Orlando Airport Marriott, Orlando, Florida and many more Guest of Honor: China Miéville www.tampabaycomiccon.com/ Guest of Honor: Kelly Link Guest Scholar: Jeffrey Cohen Anime Planet Special Guest Emeritus : Brain Aldiss March 16 www.iafa.org Seminole State College Heathrow Campus Heathrow, Florida 32746 The 2011Nebula Awards nominees $10 entry badge, $15 event pass (source Locus & SFWA website) Edwin Antionio Figueroa III (voice actor) The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America announced theanimeplanet.com the nominees for the 2011 Nebula Awards (presented 2012), the nominees for the Ray Bradbury Award for Outstanding Dramatic Hatsumi Fair (anime) Presentation, and the nominees for the Andre Norton Award for March 17-18 Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy Book. -

Copy of Anime Licensing Information

Title Owner Rating Length ANN .hack//G.U. Trilogy Bandai 13UP Movie 7.58655 .hack//Legend of the Twilight Bandai 13UP 12 ep. 6.43177 .hack//ROOTS Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.60439 .hack//SIGN Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.9994 0091 Funimation TVMA 10 Tokyo Warriors MediaBlasters 13UP 6 ep. 5.03647 2009 Lost Memories ADV R 2009 Lost Memories/Yesterday ADV R 3 x 3 Eyes Geneon 16UP 801 TTS Airbats ADV 15UP A Tree of Palme ADV TV14 Movie 6.72217 Abarashi Family ADV MA AD Police (TV) ADV 15UP AD Police Files Animeigo 17UP Adventures of the MiniGoddess Geneon 13UP 48 ep/7min each 6.48196 Afro Samurai Funimation TVMA Afro Samurai: Resurrection Funimation TVMA Agent Aika Central Park Media 16UP Ah! My Buddha MediaBlasters 13UP 13 ep. 6.28279 Ah! My Goddess Geneon 13UP 5 ep. 7.52072 Ah! My Goddess MediaBlasters 13UP 26 ep. 7.58773 Ah! My Goddess 2: Flights of Fancy Funimation TVPG 24 ep. 7.76708 Ai Yori Aoshi Geneon 13UP 24 ep. 7.25091 Ai Yori Aoshi ~Enishi~ Geneon 13UP 13 ep. 7.14424 Aika R16 Virgin Mission Bandai 16UP Air Funimation 14UP Movie 7.4069 Air Funimation TV14 13 ep. 7.99849 Air Gear Funimation TVMA Akira Geneon R Alien Nine Central Park Media 13UP 4 ep. 6.85277 All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Dash! ADV 15UP All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku TV ADV 12UP 14 ep. 6.23837 Amon Saga Manga Video NA Angel Links Bandai 13UP 13 ep. 5.91024 Angel Sanctuary Central Park Media 16UP Angel Tales Bandai 13UP 14 ep. -

Paranoia Agent of the Title, the Mysterious PAUL DUNSCOMB Is Assistant Professor of East Assailant Known As Sh¬Nen Bat

Media Section APAN’S LOST DECADE, ABOUT 1992 ate postwar generation that rebuilt Japan and TO 2003, encompassed the systemic created the era of high speed economic Jeconomic, political, and social crisis left growth with young Japanese born of the bub- by the collapse of the bubble economy. Dur- ble economy and the lost decade, particularly ing that time Japan seemed to lose direction, Kozuka Makoto, the boy who claims to be and the Japanese, afflicted by youth violence, Shonen Bat—but in fact is not. Kon, playing alienation, and the aftereffects of a spending on this sense of bewilderment, makes a won- spree that brought ruinous debt and spiritual derfully subversive suggestion. Perhaps the emptiness, were left to wonder what their greatest threat facing Japan is a national sen- hard work since the end of World War Two PARANOIA sibility, shaped by the desires of teenage girls had accomplished. Anyone who wants to who seek relief in the anodyne cuteness of understand the existential angst that gripped AGENT popular characters (thereby escaping the the Japanese during this period should look harshness of reality), and by teenage boys at this anime series from Satoshi Kon. who retreat into the virtual world of role play- THE SERIES NOMINALLY CENTERS ON THE ing games (to find meaning in life). The cute SEARCH FOR A TEENAGE BOY ON IN-LINE Maromi and Sh¬nen Bat are two sides of the SKATES, popularly known as Sh¬nen Bat, same coin, and both, ultimately, wreak who attacks residents of a Tokyo neighbor- destruction on Tokyo. -

Reflections of (And On) Otaku and Fujoshi in Anime and Manga

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2014 The Great Mirror of Fandom: Reflections of (and on) Otaku and Fujoshi in Anime and Manga Clarissa Graffeo University of Central Florida Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Graffeo, Clarissa, "The Great Mirror of Fandom: Reflections of (and on) Otaku and ujoshiF in Anime and Manga" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4695. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4695 THE GREAT MIRROR OF FANDOM: REFLECTIONS OF (AND ON) OTAKU AND FUJOSHI IN ANIME AND MANGA by CLARISSA GRAFFEO B.A. University of Central Florida, 2006 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2014 © 2014 Clarissa Graffeo ii ABSTRACT The focus of this thesis is to examine representations of otaku and fujoshi (i.e., dedicated fans of pop culture) in Japanese anime and manga from 1991 until the present. I analyze how these fictional images of fans participate in larger mass media and academic discourses about otaku and fujoshi, and how even self-produced reflections of fan identity are defined by the combination of larger normative discourses and market demands. -

Reflections on the Translation of Gender in Perfect Blue, an Anime Film by Kon Satoshi.” In: Pérez L

Recibido / Received: 29/01/2017 Aceptado / Accepted: 08/11/2017 Para enlazar con este artículo / To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6035/MonTI.2019.ne4.11 Para citar este artículo / To cite this article: Josephy-Hernández, Daniel E. (2019) “Reflections on the translation of gender in Perfect Blue, an anime film by Kon Satoshi.” In: Pérez L. de Heredia, María & Irene de Higes Andino (eds.) 2019. Multilingüismo y representación de las identidades en textos audiovisuales / Multilingualism and representation of identities in audiovisual texts. MonTI Special Issue 4, pp. 309-342. REFLECTIONS ON THE TRANSLATION OF GENDER IN PERFECT BLUE, AN ANIME FILM BY KON SATOSHI Daniel E. Josephy-Hernández [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica Abstract Perfect Blue (1997) is an anime (Japanese animation) film directed by Kon Satoshi. The film revolves around a female idol (a pop star) named Mima who quits her career as an idol to become an actress, and how she gradually loses her mind. This article presents anime as an important pop culture phenomenon with a massive influence world- wide. This article examines the gender stereotypes promulgated by this phenomenon and proposes a different reading of the work of Kon by comparing how the gender roles are portrayed in the different versions: The Japanese original and its yakuwarigo or “scripted speech” (Kinsui and Yamakido 2015) and the US English subtitles and dubbing. Methodologically, the analysis relies on close observation of the use of the Japanese first and second person pronouns and sentence-final particles in the charac- ters’ language, since “the use of these features is known to be highly gender-dependent” (Hiramoto 2013: 55). -

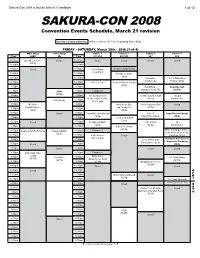

Sakura-Con 2008 Schedule, March 21 Revision 1 of 12

Sakura-Con 2008 schedule, March 21 revision 1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2008 FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (4 of 4) Panels 5 Autographs Console Arcade Music Gaming Workshop 1 Workshop 2 Karaoke Main Anime Theater Classic Anime Theater Live-Action Theater Anime Music Video FUNimation Theater Omake Anime Theater Fansub Theater Miniatures Gaming Tabletop Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Youth Matsuri Convention Events Schedule, March 21 revision 3A 4B 615-617 Lvl 6 West Lobby Time 206 205 2A Time Time 4C-2 4C-1 4C-3 Theater: 4C-4 Time 3B 2B 310 304 305 Time 306 Gaming: 307-308 211 Time Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 8:00am Karaoke setup 8:00am 8:00am The Melancholy of Voltron 1-4 Train Man: Densha Otoko 8:00am Tenchi Muyo GXP 1-3 Shana 1-4 Kirarin Revolution 1-5 8:00am 8:00am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am Haruhi Suzumiya 1-4 (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-PG D) 8:30am (SC-14 VSD, dub) (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-G) 8:30am 8:30am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (1 of 4) (SC-PG SD, dub) 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am (9:15) 9:00am 9:00am Karaoke AMV Showcase Fruits Basket 1-3 Pokémon Trading Figure Pirates of the Cursed Seas: Main Stage Turbo Stage Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Panels 4 Open Mic -

JUNE 2017 Dealer Guide

JUNE 2017 Dealer Guide FEATURING TONI ERDMANN PERFECT STRANGERS GLEASON LE RIDE LOVE AND TIME TRAVEL DAVID LYNCH: THE ART LIFE LOVE AND TIME TRAVEL AVAILABLE: 07 JUN 2017 SALES POINTS: YEAR OF PRODUCTION: 2016 FORMAT: DVD • LOVE AND SCI FI: The perfect combo! CATALOGUE NUMBER: MMA9212 • CUTE AND QUIRKY: A gem of a film, with lovely, natural performances. PRICE: $20.15 EX. GST (WSP) NUMBER OF DISCS: 1 • WHO'S THAT GUY?: Featuring WILDERPEOPLE star Julian Dennison in a super-funny CUT-OFF: 07 MAY 2017 role. RATING: M MARKETING PLAN: GENRE: COMEDY/DRAMA/ROMANCE COUNTRY: NEW ZEALAND • Social media advertising to film festival fans. RUN TIME: 89 MINUTES LANGUAGE: ENGLISH SPECIAL FEATURES: CAST AND CREW: Hayden J Weal Michelle Ny • A moment with director Hayden J. Weal at the New Zealand International Film Festival Julian Dennison • Extensive behind the scenes vlogs from Hayden DAN IS HAVING A VERY WEIRD DAY... When emotionally isolated barista Dan Duncombe starts receiving strange messages on the inside of his bedroom window, he is forced to become involved with the lives of the people around him ... and by changing their lives, he changes his own. LOVE AND TIME TRAVEL will appeal to audiences who enjoyed THE INFINITE MAN, ABOUT TIME. Visit the website for more information © Madman Entertainment Pty. Ltd. All rights reserved. GLEASON AVAILABLE: 07 JUN 2017 SALES POINTS: YEAR OF PRODUCTION: 2016 FORMAT: DVD • SUNDANCE HIT: One of the best-reviewed titles of the Sundance film festival CATALOGUE NUMBER: MMA9203 • A LOT OF HEART: You can't help but love the determined, courageous Steve Gleason PRICE: $20.15 EX. -

Numero Kansi Arvostelut Artikkelit / Esittelyt Mielipiteet Muuta 1 (1/2005

Numero Kansi Arvostelut Artikkelit / esittelyt Mielipiteet Muuta -Full Metal Panic (PAN Vision) (Mauno Joukamaa) -DNAngel (ADV) (Kyuu Eturautti) -Final Fantasy Unlimited (PAN Vision) (Jukka Simola) -Kissankorvanteko-ohjeet (Einar -Neon Genesis Evangelion, 2s (Pekka Wallendahl) - Pääkirjoitus: Olennainen osa animen ja -Jin-Roh (Future Film) (Mauno Joukamaa) Karttunen) -Gainax, 1s (?, oletettavasti Pekka Wallendahl) mangan suosiota on hahmokulttuuri (Jari -Manga! Manga! The world of Japanese comics (Kodansha) (Mauno Joukamaa) -Idän ihmeitä: Natto (Jari Lehtinen) 1 -Megumi Hayashibara, 1s (?, oletettavasti Pekka Wallendahl) Lehtinen, Kyuu Eturautti) -Salapoliisi Conan (Egmont) (Mauno Joukamaa) -Kotimaan katsaus: Animeunioni, -Makoto Shinkai, 2s (Jari Lehtinen) - Kolumni: Anime- ja mangakulttuuri elää (1/2005) -Saint Tail (Tokyopop) (Jari Lehtinen) MAY -Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children, 1s (Miika Huttunen) murrosvaihetta, saa nähdä tuleeko siitä -Duel Masters (korttipeli) (Erica Christensen) -Fennomanga-palsta alkaa -Kuukauden klassikko: Saiyuki, 2s (Jari Lehtinen) valtavirta vai floppi (Pekka Wallendahl) -Duel Masters: Sempai Legends (Erica Christensen) -Animea TV:ssä alkaa -International Ragnarök Online (Jukka Simola) -Star Ocean: Till The End Of Time (Kyuu Eturautti) -Star Ocean EX (Geneon) (Kyuu Eturautti) -Neon Genesis Evangelion (PAN Vision) (Mikko Lammi) - Pääkirjoitus: Cosplay on harrastajan -Spiral (Funimation) (Kyuu Eturautti) -Cosplay, 4s (Sefie Rosenlund) rakkaudenosoitus (Mauno Joukamaa) -Hopeanuoli (Future Film) (Jari Lehtinen) -

Opinnäytetyö (AMK)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Theseus Opinnäytetyö (AMK) Viestinnän koulutusohjelma Animaatio 2015 Miira Tonteri UNIEN RAJOILLA – unimaailma Satoshi Konin animaatioissa OPINNÄYTETYÖ (AMK) | TIIVISTELMÄ TURUN AMMATTIKORKEAKOULU Viestintä| Animaatio 2015 | 25 Vesa Kankaanpää, Eija Saarinen Miira Tonteri UNIEN RAJOILLA Kirjallisessa opinnäytetyössäni käsittelen japanilaisen animaatio-ohjaajan Satoshi Konin teoksissaan toistuvasti käyttämää uni-teemaa. Konin teokset tutkivat kaikki ihmismie- len syvimpiä koukeroita sekä illuusion ja todellisuuden sekoittumista. Pyrkimyksenäni on löytää ja määritellä minkälaisia tehokeinoja Kon on käyttänyt luodakseen tämän teoksilleen ominaisen unenomaisen tunnelman. Olen seurannut Konin uraa jo vuosia ja käynyt tänä aikana läpi hänen elokuviensa tee- moja ja teknistä toteutusta. Koen myös tietynlaista sielujen sympatiaa häntä kohtaan, sillä tunnen itsekin vetoa ihmismielen sisäisen maailman kuvaamiseen omissa töissäni. Satoshi Konin tapa käsitellä subjektiivista todellisuutta elokuvissaan on erittäin omape- räinen, ja opinnäytetyöni kautta pyrin paitsi ymmärtämään hänen elokuviaan parem- min myös löytämään omaa näkökulmaani ja tyyliäni unimaailman kuvaamiseen. ASIASANAT: animaatio, animaatioelokuvat, anime, animaattorit, elokuvaohjaajat, elokuvaohjaus, ohjaajat BACHELOR´S THESIS | ABSTRACT TURKU UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Film and Media | Animation 2015| 25 Vesa Kankaanpää, Eija Saarinen Miira Tonteri ON THE BORDERLINE OF DREAMS In my bachelor's thesis I'm pondering about the Japanese animation director Satoshi Kon's style of using repeatingly a dream-theme in his works. All of his films are circling around the deepest bits of human mind and the blending of illusion and reality. My aim is to find and define the ways how Kon has created this dream-like feeling in his works. I've been following Kon's career for years and studied the themes and technical execu- tions in his films during this time.