Thomas Willing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resources for Teachers John Trumbull's Declaration Of

Resources for Teachers John Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence CONVERSATION STARTERS • What is happening with the Declaration of Independence in this painting? o The Committee of Five is presenting their draft to the President of the Continental Congress, John Hancock. • Both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson apparently told John Trumbull that, if portraits couldn’t be painted from life or copied from other portraits, it would be better to leave delegates out of the scene than to poorly represent them. Do you agree? o Trumbull captured 37 portraits from life (which means that he met and painted the person). When he started sketching with Jefferson in 1786, 12 signers of the Declaration had already died. By the time he finished in 1818, only 5 signers were still living. • If you were President James Madison, and you wanted four monumental paintings depicting major moments in the American Revolution, which moments would you choose? o Madison and Trumbull chose the surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga, the surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, the Declaration of Independence, and the resignation of Washington. VISUAL SOURCES John Trumbull, Declaration of Independence (large scale), 1819, United States Capitol https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Declaration_of_Independence_(1819),_by_John_Trumbull.jpg John Trumbull, Declaration of Independence (small scale), 1786-1820, Trumbull Collection, Yale University Art Gallery https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/69 John Trumbull and Thomas Jefferson, “First Idea of Declaration of Independence, Paris, Sept. 1786,” 1786, Gift of Mr. Ernest A. Bigelow, Yale University Art Gallery https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/2805 PRIMARY SOURCES Autobiography, Reminiscences and Letters of John Trumbull, from 1756 to 1841 https://archive.org/details/autobiographyre00trumgoog p. -

“A Fickle, and Confused Multitude”: War and Politics in Revolutionary

“A Fickle, and Confused Multitude”: War and Politics in Revolutionary Philadelphia, 1750-1783 by Paul Langston B.A., Stephen F. Austin State University, 1997 M.A., University of North Texas, 2006 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2013 i This thesis entitled: “A Fickle, and Confused Multitude”: War and Politics in Revolutionary Philadelphia, 1750-1783 written by Paul Langston has been approved for the Department of History (Professor Virginia DeJohn Anderson) (Professor Fred W. Anderson) Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Langston, Paul D. (Ph.D., History Department) “A Fickle, and Confused Multitude”: War and Politics in Revolutionary Philadelphia, 1750-1783 Thesis directed by Professor Virginia DeJohn Anderson ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the crucial link between war and politics in Philadelphia during the American Revolution. It demonstrates how war exacerbated existing political conflicts, reshaped prewar political alliances, and allowed for the rise of new political coalitions, all developments that were tied to specific fluctuations in the progress of the military conflict. I argue that the War for Independence played a central role in shaping Philadelphia’s contentious politics with regard to matters of balancing liberty and security. It was amidst this turmoil that the new state government sought to establish its sovereignty and at the same time fend off Pennsylvania’s British enemies. -

An Holy Experiment and the Separation of 1827-1828

1 An Holy Experiment and The Separation of 1827-1828 Randal L Whitman 2020 William Penn seized the opportunity granted to him in 1681. The British Crown owed his late father, an Admiral of the Royal Navy, a considerable debt, and Penn persuaded His Royal Highness Charles II to pay it off by granting him Proprietary rights to Pennsylvania. In 1682, Penn set in motion what he called “an holy experiment:” a colony, run by Quakers, and dedicated to Quaker principles, yet open to all religions. In so doing, Penn let fly a flaming arrow which arced across the heaven of slow time to embed itself into Arch Street meeting house in Philadelphia, one-hundred-forty-five years later, at the opening session of the yearly meeting on April 16, 1827, and set it aflame. Mystical and Evangelical The flame of contention that drove Friends apart was at least in part doctrinal in nature. Howard Haines Brinton’s major work, Friends for 300 Years1, focuses considerable attention on what he calls the “tension” between the inward and outward aspects of Quakerism, otherwise called its mystical and evangelical aspects. Primitive is a term frequently used as a synonym for mystical in this context.2 Brinton suggests that the main attraction that George Fox’s new religion brought in the mid-seventeenth century was its strong dependence on inward revelation--that is, the individual’s self-discovery of God and God’s Truth within himself--as opposed to the individual’s dependence on outward authority—clergy and Scriptures. For poor, mostly illiterate or semi-literate peoples, this discovery was electrifying. -

A Portrait of the First Continental Congress

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2009 Fifty gentlemen total strangers: A portrait of the First Continental Congress Karen Northrop Barzilay College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Barzilay, Karen Northrop, "Fifty gentlemen total strangers: A portrait of the First Continental Congress" (2009). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623537. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-61q6-k890 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fifty Gentlemen Total Strangers: A Portrait of the First Continental Congress Karen Northrop Barzilay Needham, Massachusetts Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 1998 Bachelor of Arts, Skidmore College, 1996 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program The College of William and Mary January 2009 © 2009 Karen Northrop Barzilay APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ~ilayd Approved by the Committee, October, 2008 Commd ee Chair Professor Robert A Gross, History and American Studies University of Connecticut Professor Ronald Hoffman, History Director, Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture The College of William and Mary Associate Professor Karin Wuff, History and encan Studres The College of William and Mary ABSTRACT PAGE When news of the Coercive Acts reached the mainland colonies ofBritish North America in May 177 4, there was no such thing as a Continental Congress. -

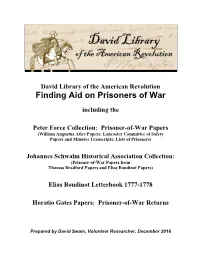

Finding Aid on Prisoners of War

David Library of the American Revolution Finding Aid on Prisoners of War including the Peter Force Collection: Prisoner-of-War Papers (William Augustus Atlee Papers; Lancaster Committee of Safety Papers and Minutes Transcripts; Lists of Prisoners) Johannes Schwalm Historical Association Collection: (Prisoner-of-War Papers from Thomas Bradford Papers and Elias Boudinot Papers) Elias Boudinot Letterbook 1777-1778 Horatio Gates Papers: Prisoner-of-War Returns Prepared by David Swain, Volunteer Researcher, December 2016 Table of Contents Manuscript Sources—Prisoner-of-War Papers 1 Peter Force Collection (Library of Congress) 1 Johannes Schwalm Historical Association Collection (Historical Society of Pennsylvania; Library of Congress) 2 Elias Boudinot Letterbook (State Historical Society 3 of Wisconsin) Horatio Gates Papers (New York Historical Society) 4 General Index 5 Introduction 13 Overview 13 Untangling the Categories of Manuscripts from their 15 Interrelated Sources People Involved in Prisoner-of-War Matters 18 Key People 19 Elias Boudinot 20 Thomas Bradford 24 William Augustus Atlee 28 Friendships and Relationships 31 American Prisoner-of-War Network and System 32 Lancaster Committee of Safety Papers and Minutes 33 Prisoner-of-War Lists 34 References 37 Annotated Lists of Contents: 41 Selected Prisoner-of-War Documents William Augustus Atlee Papers 1758-1791 41 (Peter Force Collection, Series 9, Library of Congress) LancasterCommittee of safety Papers 1775-1777 97 (Peter Force Collection, Series 9, Library of Congress) -

The Politics of the Declaration of Independence Before the Civil War

BETWEEN THE STATES AND THE SIGNERS: THE POLITICS OF THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE BEFORE THE CIVIL WAR BERNADETTE MEYLER* INTRODUCTION It is almost impossible to conjure the thought of the Declaration of Independence today without also raising the specters of the signers. Commonplace invocations of “John Hancock” stand in for the prototypical signature, and elementary school children throughout the country learn details about the lives of the signers.1 The signers did not, however, authorize the Declaration simply for themselves. As Jacques Derrida wrote in 1986, “[t]he signature invents the signer,” meaning that the signatures affixed to the Declaration in the name of the “People” created the very people whom the document invoked.2 But simply invoking this People does not answer many questions about its identity; who constitutes the People temporally and spatially continues to trouble political theorists.3 * Carl and Sheila Spaeth Professor of Law, Stanford University. I am grateful to Alexander Tsesis, Matthew Smith, Jack Rakove, Amalia Kessler, and Jeffrey Rosen, as well as to the participants in the Stanford Faculty Workshop, the Loyola Los Angeles Faculty Workshop, and the conference on “Constitutional Culture” at Queens University for assistance in thinking through this Article. 1. The Oxford English Dictionary defines “John Hancock” simply as “a signature.” 2 A SUPPLEMENT TO THE OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY 431 (R.W. Burchfield ed., 1976). 2. Jacques Derrida, Declarations of Independence, 15 NEW POL. SCI. 7, 10 (1986). 3. See, e.g., PAULINA OCHOA ESPEJO, THE TIME OF POPULAR SOVEREIGNTY: PROCESS AND THE DEMOCRATIC STATE (2011); JASON FRANK, CONSTITUENT MOMENTS: ENACTING THE PEOPLE IN POSTREVOLUTIONARY AMERICA (2010). -

The Google Challenge to Common Law Myth James Maxeiner University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship Spring 2015 A Government of Laws Not of Precedents 1776-1876: The Google Challenge to Common Law Myth James Maxeiner University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Common Law Commons, Computer Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation A Government of Laws Not of Precedents 1776-1876: The Google Challenge to Common Law Myth, 4 Brit. J. Am. Legal Stud. 137 (2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A GOVERNMENT OF LAWS NOT OF PRECEDENTS 1776-1876: THE GOOGLE CHALLENGE TO COMMON LAW MYTH* James R. Maxeiner"" ABSTRACT The United States, it is said, is a common law country. The genius of American common law, according to American jurists, is its flexibility in adapting to change and in developing new causes of action. Courts make law even as they apply it. This permits them better to do justice and effectuate public policy in individual cases, say American jurists. Not all Americans are convinced of the virtues of this American common law method. Many in the public protest, we want judges that apply and do not make law. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Volume 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Preface ................................................................................................................................................xvii Introduction ........................................................................................................................................xxv A Andrew Adams ...................................................................................................................................... 1 John Adams ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Samuel Adams ..................................................................................................................................... 12 Thomas Adams .................................................................................................................................... 18 Robert Alexander ................................................................................................................................. 19 Andrew Allen ....................................................................................................................................... 21 John Alsop ........................................................................................................................................... 24 Benjamin Andrew ................................................................................................................................ 27 Annapolis State -

Pennsylvania's Loyalists and Disaffected in the Age of Revolution: Defining the Terrain of Reintegration, 1765-1800 Rene J

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-19-2018 Pennsylvania's Loyalists and Disaffected in the Age of Revolution: Defining the Terrain of Reintegration, 1765-1800 Rene J. Silva Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC006568 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Legal Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Silva, Rene J., "Pennsylvania's Loyalists and Disaffected in the Age of Revolution: Defining the Terrain of Reintegration, 1765-1800" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3670. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3670 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida PENNSYLVANIA’S LOYALISTS AND DISAFFECTED IN THE AGE OF REVOLUTION: DEFINING THE TERRAIN OF REINTEGRATION, 1765-1800 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by René José Silva 2018 To: Dean John F. Stack, Jr. choose the name of dean of your college/school Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs choose the name of your college/school This dissertation, written by René José Silva, and entitled Pennsylvania's Loyalists and Disaffected in the Age of Revolution: Defining the Terrain of Reintegration, 1765-1800, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

Pennsylvania Politic Ians A~'D the Signing

PENNSYLVANIA POLITIC IANS A~'D THE SIGNING OF THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE A Thesis Presented to the Division of Social Sciences Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Honald:[. ICo lenbrander August 1973 · J AC KNO \Y'LEDGMENTS I wish to express my appreciation to Dr. John J. Zimmerman for his courteous and exacting assistance and criticism, and to Dr. William H. Seiler and Dr. Glenn Torrey and the other members of the history faculty for their assistance and encouragement through the past two years. The personnel at the William Allen White Library and the library at Southwest Minnesota State College who gave so generously of t~eir time deserve acknowledgment, and to Dr. H. Warren Gardner of Southwest Minnesota State a special "thank you" for leading me down the path of history. Without the assistance of K.K.S. and S.W. this paper would not have reached its final form. To my parents "thanks" for so much. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cho.pter Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. PENNSYLVANIA AND ITS HOVEMENT TOl-lARDS INDEPENDENCE • • • • • • • • • • • • 4 J. BIOGHAPHICAL AND HISTOHICAL SKETCHES OF TIIE PENNSYLVANIA DELEGATION TO THE CONTINENTAL CONGHESS 4L~ 4. CONCLUSION . 116 l3IBLIOGHAPHY . 121 111 Chapter 1 INTHODUCTION There were nine men from the state of Pennsylvania who signed the Declaration of Independence. Of these nlne slgners only three voted for the document. Pennsylvani<l was unique in this since most of the other colonies voted with only a few dissenters. Because of Pennsylvania's stra tegic geographical position its concurrence with the Congressional action of early July, 1776, was of the utmost importance to the success of the united effort. -

Robert Morris, the Financier of the American Revolution. a Sketch

ROBERT MORRIS I THE FINANCIER OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION I I A SKETCH BY CHARLES HENRY HART IIistoriographer of the Numismatic and Antiquarian Society of Pl~iladolphia; Corresponding Member of the Essex Institute, Salern, Yassachusotts; The New England Historic Genealogical Society; The New York Genealogical and Biographical Society; The Maine Historical Society; The Long Island IIistoricai Society, etc. etc. etc., and Author of " An Iiintorical Sketch of Kational Medals ;" '' Remarks on Tt~basco, Mexico;" "Memoir of William Hickli~~gPrescott;" "Biographical Sketch of Abr:lham Lincoln;" "Yiscourbe 011 Gulian C. Verplanck ;" " Memoir of George Ticknor ;" " Bibliographia. Linco111im;l;" '' Life of Colonel John Kixon," etc. etc. ete. RICPRINTRD FROX THE PRKNSY1,VAKIA MAGAZINF: OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY 'I PHILAnELPHIA: COLLINS, PRINTER. NOTE. The following Monograph was presented, at the Centennial Celebration of the Adoption of the "Resolutions Respecting Independency," in Inde- pendence Hall, Philadelphia, July lst, 1876. (Centennial Collection.) 12 presenting a brief memoir of the life of Robert Morris, it is impossible to forget the biting sarcasm and sharp wit of Rufus Choate's memorable toast,--" Pelmsylvauia's two lllost distinguished citizens, Robert Morris, a native of Great Britain, and Benjaniiu Franklin, a native of Massachusetts." It is to portray the life of one of these "citizens" that 1have been invited here today. Robert Morris, the Financier of the American Revolution, was born in Liverpool, Kingdom of Great Britain, on the 20th of January, 1733-34, old style, or what would be, according to the modern method of computation, January 31st, 1734. His fitther, also Robert Morris, came to this country and settled at Oxford on the eastern shore of Maryland prior to the year 1740. -

Texts from Revolution Toolbox CK

Was the American Revolution Avoidable? Online Seminar Texts from the forthcoming National Humanities Center toolbox Making the Revolution: America, 1763-1791 Page # David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution , 1789, excerpt: An 1 American Looks Back at British Victory in the French and Indian War Benjamin Franklin and American clergymen on British victories in the French 2 and Indian War, 1759-1763 Thomas Pownall, The Administration of the Colonies , 1764, selections 3 Parliament [House of Commons] Debates the Stamp Act, February 6, 1765 7 • Grenville, pp. 1-2 • Townshend, pp. 4 and5 • Barré, pp. 5-6 British Merchants’ Warning to Boston Merchants on the eve of the repeal of the 13 Stamp Act, 1766 Benjamin Franklin explains the Americans’ “Ill Humour” to the British, letter to 14 The London Chronicle , Jan. 5-7, 1768 The Massachusetts Circular Letter, 1768 16 John Dickinson, Letters from a Pennsylvania Farmer , Letter 1, December 2, 17 1767 Boston Committee of Correspondence, The “Boston Pamphlet,” 1772, Section 20 A: III The Rights of the Colonists as Subjects [of England] Benjamin Franklin, Rules by Which a Great Empire May be Reduced to a Small 27 One , September 1773 First Continental Congress, Petition to the King, Fall 1774 32 First Continental Congress, [Bill of Rights], Fall 1774 35 Second Continental Congress, Olive Branch Petition, July 1775 38 Second Continental Congress, Declaration of the Causes of Taking Up Arms, 41 July 1775 Online Seminar Was the American Revolution Avoidable? 19 Oct. 2010 AAAN AAAMERICAN LLLOOKS BBBACK New York Public Library AT BBBRITISH VVVICTORY in the FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR, 1763 DAVID RAMSAYRAMSAY, The History of the American Revolution , 1789.