'Leave Us in Peace!'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Water Rights-Based Legal Mobilization of the Wayúu Against the Cercado Dam: an Effective Avenue for Court-Centered Lawfare from Below?*

The Water Rights-Based Legal Mobilization of the Wayúu against the Cercado Dam: An Effective Avenue for Court-Centered Lawfare from Below?* Sergi Vidal Parra** University of Deusto, País Vasco https://doi.org/10.7440/antipoda34.2019.03 How to cite this article: Vidal Parra, Sergi. 2019. “The Water Rights-Based Legal Mobilization of the Wayúu against the Cercado Dam: An Effective Avenue for Court-Centered Lawfare from Below?” Antípoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología 34: 45-68. https://doi.org/10.7440/ antipoda34.2019.03 Reception date: January 29, 2018; Acceptance date: August 28, 2018; Modification date: September 28, 2018. Abstract: Objective/Context: In recent years, decreasing water availability, accessibility, and quality in the Upper and Middle Guajira has led to the death of thousands of Wayúu people. This has been caused by precipitation 45 deficit and droughts and hydro-colonization by mining and hydropower projects. This study assesses the effectiveness of the Wayúu’s legal mobili- zation to redress the widespread violation of their fundamental rights on the basis of the enforceability and justiciability of the human right to water. Methodology: The study assesses the effects of the Wayúu’s legal mobiliza- tion by following the methodological approach proposed by Siri Gloppen, * This paper is result of two field studies conducted in the framework of my doctoral studies: firstly, PARALELOS a six-month research stay at the Research and Development Institute in Water Supply, Environmental Sanitation and Water Resources Conservation of the Universidad del Valle, Cali (2016-2017); secondly, the participation in the summer courses on “Effects of Lawfare: Courts and Law as Battlegrounds for Social Change” at the Centre on Law and Social Transformation (Bergen 2017). -

UNHCR Colombia Receives the Support of Private Donors And

NOVEMBER 2020 COLOMBIA FACTSHEET For more than two decades, UNHCR has worked closely with national and local authorities and civil society in Colombia to mobilize protection and advance solutions for people who have been forcibly displaced. UNHCR’s initial focus on internal displacement has expanded in the last few years to include Venezuelans and Colombians coming from Venezuela. Within an interagency platform, UNHCR supports efforts by the Government of Colombia to manage large-scale mixed movements with a protection orientation in the current COVID-19 pandemic and is equally active in preventing statelessness. In Maicao, La Guajira department, UNHCR provides shelter to Venezuela refugees and migrants at the Integrated Assistance Centre ©UNHCR/N. Rosso. CONTEXT A peace agreement was signed by the Government of Colombia and the FARC-EP in 2016, signaling a potential end to Colombia’s 50-year armed conflict. Armed groups nevertheless remain active in parts of the country, committing violence and human rights violations. Communities are uprooted and, in the other extreme, confined or forced to comply with mobility restrictions. The National Registry of Victims (RUV in Spanish) registered 54,867 displacements in the first eleven months of 2020. Meanwhile, confinements in the departments of Norte de Santander, Chocó, Nariño, Arauca, Antioquia, Cauca and Valle del Cauca affected 61,450 people in 2020, as per UNHCR reports. The main protection risks generated by the persistent presence of armed groups and illicit economies include forced recruitment of children by armed groups and gender- based violence – the latter affecting in particular girls, women and LGBTI persons. Some 2,532 cases of GBV against Venezuelan women and girls were registered by the Ministry of Health between 1 January and September 2020, a 41.5% increase compared to the same period in 2019. -

Chapter 8: Colombia

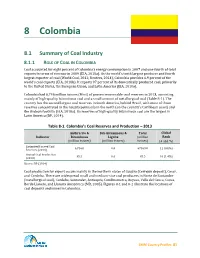

8 Colombia 8.1 Summary of Coal Industry 8.1.1 ROLE OF COAL IN COLOMBIA Coal accounted for eight percent of Colombia’s energy consumption in 2007 and one-fourth of total exports in terms of revenue in 2009 (EIA, 2010a). As the world’s tenth largest producer and fourth largest exporter of coal (World Coal, 2012; Reuters, 2014), Colombia provides 6.9 percent of the world’s coal exports (EIA, 2010b). It exports 97 percent of its domestically produced coal, primarily to the United States, the European Union, and Latin America (EIA, 2010a). Colombia had 6,746 million tonnes (Mmt) of proven recoverable coal reserves in 2013, consisting mainly of high-quality bituminous coal and a small amount of metallurgical coal (Table 8-1). The country has the second largest coal reserves in South America, behind Brazil, with most of those reserves concentrated in the Guajira peninsula in the north (on the country’s Caribbean coast) and the Andean foothills (EIA, 2010a). Its reserves of high-quality bituminous coal are the largest in Latin America (BP, 2014). Table 8-1. Colombia’s Coal Reserves and Production – 2013 Anthracite & Sub-bituminous & Total Global Indicator Bituminous Lignite (million Rank (million tonnes) (million tonnes) tonnes) (# and %) Estimated Proved Coal 6,746.0 0.0 67469.0 11 (0.8%) Reserves (2013) Annual Coal Production 85.5 0.0 85.5 10 (1.4%) (2013) Source: BP (2014) Coal production for export occurs mainly in the northern states of Guajira (Cerrejón deposit), Cesar, and Cordoba. There are widespread small and medium-size coal producers in Norte de Santander (metallurgical coal), Cordoba, Santander, Antioquia, Cundinamarca, Boyaca, Valle del Cauca, Cauca, Borde Llanero, and Llanura Amazónica (MB, 2005). -

Bogotá, Colombia – Quarterly Report January – March 2008

PROGRAMA CIMIENTOS – BOGOTÁ, COLOMBIA – QUARTERLY REPORT JANUARY – MARCH 2008 APRIL 30, 2008 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Management Systems International. PROGRAMA CIMIENTOS – BOGOTÁ, COLOMBIA – QUARTERLY REPORT JANUARY – MARCH 2008 Contracted under Task Order Contract: DFD-I-03-05-00221-00 Colombia Regional Governance & Consolidation Program CIMIENTOS DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 II. ACTIVITIES BY COMPONENT AT THE NATIONAL LEVEL .............................. 1 A. Component 1. Improving Citizen Security and Effective State Presence in Health and Education ................................................................................................. 1 B. Component 2: Building governance capacity in targeted regions ............................. 6 C. Cross-cutting component: Civil Society ................................................................. 11 III. ACTIVITIES AND CONTEXT AT THE REGIONAL LEVEL ............................... 14 A. National Level .......................................................................................................... 14 B. Bajo and Medio Atrato ............................................................................................ -

Mining-Induced Displacement and Resettlement in Colombia

Mining-induced displacement and resettlement in Colombia Socio-economic and cultural consequences of resettlements of campesinos and indigenous people - The case of the Cerrejón open pit mine in La Guajira Masterarbeit vorgelegt von Benedikt Hora bei Univ. Prof. Dr. Martin Coy Universität Innsbruck August 2014 Masterarbeit Mining-induced displacement and resettlement in Colombia Socio-economic and cultural consequences of resettlements of campesinos and indigenous people – The case of the Cerrejón open pit mine in La Guajira Verfasser Benedikt Hora B.Sc. Angestrebter akademischer Grad Master of Science (M.Sc.) eingereicht bei Herrn Univ. Prof. Dr. Martin Coy Institut für Geographie Fakultät für Geo- und Atmosphärenwissenschaften an der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides statt durch meine eigenhändige Unterschrift, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebene Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Alle Stellen, die wörtlich oder inhaltlich an den angegebenen Quellen entnommen wurde, sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form noch nicht als Magister- /Master-/Diplomarbeit/Dissertation eingereicht. _______________________________ Innsbruck, August 2014 Unterschrift Contents CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Preface -

New Records of Amphisbaena Medemi Gans & Mathers, 1977 (Squamata

10TH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE Check List the journal of biodiversity data NOTES ON GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION Check List 11(1): 1526, January 2015 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15560/11.1.1526 ISSN 1809-127X © 2015 Check List and Authors New records of Amphisbaena medemi Gans & Mathers, 1977 (Squamata: Amphisbaenidae) from the Caribbean region of northern Colombia Fabio Leonardo Meza-Joya Grupo de Estudios en Biodiversidad, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This report extends the distribution range of expands the ranges of distribution, elevation, and habitat Amphisbaena medemi to the southeast foothills of the Sierra type of A. medemi. Nevada de Santa Marta and western foothills of the Serranía During 2011, two new specimens of Amphisbaena medemi del Perijá in La Guajira department, Colombia. These records (Figure 1) were recorded from two new localities in the offer a more detailed picture of the species’ distributional Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and Serranía del Perijá in La range along the Caribbean region of Colombia and represent Guajira department (Colombia). Collection of specimens the first observation of the species in a transitional zone was authorized by Corporación Autónoma Regional de La between dry and moist tropical forest. Guajira (Acuerdo 0021–2011). One adult female specimen, SVL 146.7 mm, was collected in the Corregimiento La Sierrita, Key words: Amphisbaena medemi, Sierra Nevada de Santa municipality of San Juan del Cesar (approximately 214 km Marta, Serranía del Perijá, dry tropical forest, moist tropical east-northeast of its type locality; Figure 2) in the southeast forest foothills of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. -

(COP) to the Protocol Concerning Pollution from Land- Based

UNITED NATIONS EP Distr. LIMITED UNEP(DEPI)/CAR IG.41/INF.3 29 May 2019 Fourth Meeting of the Contracting Parties (COP) Original: ENGLISH to the Protocol Concerning Pollution from Land- Based Sources and Activities (LBS) in the Wider Caribbean Region Roatan, Honduras, 4 June 2019 STATE OF THE CARTAGENA CONVENTION AREA REPORT An Assessment of Marine Pollution from Land-Based Sources and Activities in the Wider Caribbean Region STATE OF THE CARTAGENA CONVENTION AREA REPORT An Assessment of Marine Pollution from Land-based Sources and Activities in the Wider Caribbean Region May 2019 UNEDITED 2 CREDITS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Coordination: Cartagena Convention Secretariat, UN Environment CEP (Christopher Corbin) Lead author: Sherry Heileman (Consultant) Contributing lead author: Liana Talaue-McManus (Consultant) Contributing authors: Christopher Corbin (UN Environment CEP) Linroy Christian (Antigua & Barbuda) Darryl Banjoo (Trinidad & Tobago) Stephanie Adrian (USA, Chair LBS Monitoring and Assessment Working Group) Emilio Mayorga, University of Washington Other contributors LBS Monitoring and Assessment Working Group LBS Protocol Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC) Basel Convention Regional Centre for Training and Technology Transfer for the Caribbean Region (BCRC Caribbean) Regional Marine Pollution Emergency, Information and Training Centre – Caribe (REMPEITC) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Financial support Integrating Water, Land, and Ecosystems Management in Caribbean Small Island Developing States (IWEco) Project (GEF/UN Environment) -

Narcotics Funded Terrorists/Extremist Groups

A GLOBAL OVERVIEW OF NARCOTICS-FUNDED TERRORIST AND OTHER EXTREMIST GROUPS A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the Department of Defense May 2002 Researchers: LaVerle Berry Glenn E. Curtis Rex A. Hudson Nina A. Kollars Project Manager: Rex A. Hudson Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax: 202−707−3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://www.loc.go v/rr/frd/ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Narcotics-Funded Terrorist/Extremist Groups PREFACE This global survey, based entirely on open sources, is intended to provide an assessment of the nexus between selected anti-U.S. terrorist and extremist groups in the world and organized crime, specifically drug trafficking, and how this relationship might be vulnerable to countermeasures. More specifically, the aim is to help develop a causal model for identifying critical nodes in terrorist and other extremist networks that can be exploited by Allied technology, just as counterdrug technology has been used in the war against drug trafficking. To this end, the four analysts involved in this study have examined connections between extremist groups and narcotics trafficking in the following countries, listed by region in order of discussion in the text: Latin America: Triborder Region (Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay), Colombia, and Peru; the Middle East: Lebanon; Southern Europe (Albania and Macedonia); Central Asia: Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan; and East Asia: Philippines. These are preliminary, not definitive, surveys. Most of the groups examined in this study have been designated foreign terrorist organizations by the U.S. -

Colombia: COVID-19 Impact of Government Measures Briefing Note – 16 April 2020

Colombia: COVID-19 Impact of government measures Briefing Note – 16 April 2020 The first case of COVID-19 was reported in Colombia on 6 March 2020. The government has since implemented a series of containment measures to mitigate disease spread Measure Type of Measure Description and strengthen the Colombian health system. The containment measures themselves Decrees Lockdown National quarantine from 25 March to 27 April: have a secondary impact, affecting humanitarian needs among vulnerable population 457, 531 preventive isolation for all inhabitants of groups. Colombia, with exceptions for example for health The purpose of this report is to support the humanitarian response in Colombia to services and to meet basic needs. understand the following issues: Decree 457 Movement Suspension of national air travel from 25 March to How do government measures mitigate the epidemic impact • on restrictions 13 April. vulnerable population groups? Decree 412 Border closure Closure of all sea, land, and river borders from 17 • What are their factors of vulnerability in relation to the measures? March until 30 May. • Which humanitarian needs are likely to arise in the short to medium term? Social distancing All events limited to 50 participants. The primary focus of the analysis is on Colombian internally displaced people (IDPs), Venezuelan refugees and migrants, and, to a lesser extent, Colombian host Social distancing Suspension of in-person classes until 31 May. communities and Colombian returnees, although some findings and conclusions apply to broader population groups (such as low-income households in general). This report Overview of selected government measures. Sources: Government of Colombia does not present specialised health analysis and does not focus on government 06/04/2020, 23/03/2020, 16/03/2020, 16/03/2020, 08/04/2020; El Tiempo 15/03/2020. -

BIOTA COLOMBIANA ISSN Impreso 0124-5376 Volumen 20 · Número 1 · Enero-Junio De 2019 ISSN Digital 2539-200X DOI 10.21068/C001

BIOTA COLOMBIANA ISSN impreso 0124-5376 Volumen 20 · Número 1 · Enero-junio de 2019 ISSN digital 2539-200X DOI 10.21068/c001 Atropellamiento vial de fauna silvestre en la Troncal del Caribe Amaryllidaceae en Colombia Adiciones al inventario de copépodos de Colombia Nuevos registros de avispas en la región del Orinoco Herpetofauna de San José del Guaviare Escarabajos estercoleros en Aves en los páramos de Antioquia Oglán Alto, Ecuador y el complejo de Chingaza Biota Colombiana es una revista científica, periódica-semestral, Comité Directivo / Steering Committee que publica artículos originales y ensayos sobre la biodiversi- Brigitte L. G. Baptiste Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos dad de la región neotropical, con énfasis en Colombia y países Alexander von Humboldt vecinos, arbitrados mínimo por dos evaluadores externos. In- M. Gonzalo Andrade Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia cluye temas relativos a botánica, zoología, ecología, biología, Francisco A. Arias Isaza Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras limnología, conservación, manejo de recursos y uso de la bio- “José Benito Vives De Andréis” - Invemar diversidad. El envío de un manuscrito implica la declaración Charlotte Taylor Missouri Botanical Garden explícita por parte del (los) autor (es) de que este no ha sido previamente publicado, ni aceptado para su publicación en otra Editor / Editor revista u otro órgano de difusión científica. El proceso de arbi- Rodrigo Bernal Independiente traje tiene una duración mínima de tres a cuatro meses a partir Editor de artículos de datos / Data papers Editor de la recepción del artículo por parte de Biota Colombiana. To- Dairo Escobar Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos das las contribuciones son de la entera responsabilidad de sus Alexander von Humboldt autores y no del Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Bioló- Asistente editorial / Editorial assistant gicos Alexander von Humboldt, ni de la revista o sus editores. -

Response to the Independent Panel's Assessment Of

RESPONSE TO THE INDEPENDENT PANEL’S ASSESSMENT OF CERREJÓN’S SOCIAL ENGAGEMENT PRACTICES Bogotá, Colombia. April 2008 I. Introduction In August 2007, Cerrejón and its shareholders invited four independent external experts to evaluate the Company’s social responsibility programs, both past and present. The Panel’s terms of reference specifically included the consideration of the mine’s long term social impact and outstanding issues of concern. The Panel was made up of four internationally recognised experts in the area of social development and was chaired by Dr. John Harker, President of the University of Cape Breton in Canada. It worked from September 2007 to February 2008. It also included: Salomón Kalmanovitz, Dean of Economic and Administrative Sciences at Jorge Tadeo Lozano University, and former member of the Board of Governors of the Banco de la República (Central Bank) of Colombia; Elena Serrano, of Casa de La Paz Foundation, a non-governmental organization with headquarters in Chile which promotes peace, social development, and environmental awareness; and Nick Killick of International Alert, a non-governmental organization based in the United Kingdom, dedicated to building peace in developing countries. To support their work, the Panel retained the services of an expert consultancy. The Social Capital Group, a consulting firm with offices in Perú and the United States, was chosen by the Panel to undertake detailed field work and assist in the development of their findings and recommendations. Cerrejón management and its shareholders believe that the Independent Panel’s final report 1 provides valuable insights into the resolution of a number of legacy issues and a sound guide to the future development of the company’s environmental and social programs. -

Fact Sheet #1, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2020 February 12, 2020

VENEZUELA REGIONAL CRISIS FACT SHEET #1, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2020 FEBRUARY 12, 2020 HUMANITARIAN FUNDING NUMBERS AT HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE FOR THE VENEZUELA REGIONAL CRISIS Government of Colombia grants RESPONSE IN FYs 2017–2019 citizenship to children born in Colombia to Venezuelan parents USAID/OFDA1 $117,078,942 4.8 Measles-related deaths in Venezuela USAID/FFP2 $147,117,407 decline by 96 percent in 2019 following million country-wide vaccination campaign State/PRM3 $208,206,327 Estimated Number of Government of Brazil grants refugee Venezuelan Migrants and status to 37,000 Venezuelans Refugees $472,402,676 R4V – February 2020 6.5 million KEY DEVELOPMENTS The 2020 Global Humanitarian Overview, released by the UN in December, requests Projected Number of Venezuelan Migrants and $2.1 billion to support the humanitarian response for the Venezuela regional crisis in Refugees by End of 2020 2020. The appeal includes $750 million for humanitarian efforts in Venezuela to reach R4V – November 2019 3.5 million of the estimated 7 million people in need, and $1.35 billion to reach approximately 4 million crisis-affected individuals across 17 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, as outlined in the 2020 Regional Refugee and Migrant Response Plan $750 for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (RMRP). The number of measles-related deaths in Venezuela declined by 96 percent in 2019 million compared to the previous year, following a country-wide vaccination campaign between Funding Requirement for April 2018 and July 2019 that reached nearly 9 million children ages 6 months–15 years, 2020 Humanitarian with funding from USAID/OFDA and other donors.