New Monasticism Names an Impulse That Is Trying to Incarnate Itself in the New Generation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celtic Newsletter – Fall 2016

ROANOKE CATHOLIC SCHOOL CELTIC NEWSLETTER FALL 2016 INSIDE: Back on “The Hill,” alumnus David Turk resurrects the Celtics volleyball program — winning games, fans and, most importantly, hearts MESSAGE FROM PRINCIPAL & HEAD OF SCHOOL Dear Alumni, School Families and Friends of Roanoke Catholic, I have an opportunity in this edition of our Celtic Newsletter to spotlight some wonderful “highlights” at Roanoke Catholic School. We have a tremendous volunteer base in our school community, but in all my years of service — from college and public school work to my partnership with Roanoke Catholic — I have never been so incredibly impressed with four parents who truly epitomize the servant’s heart and giving spirit of our faith. I must share with you how blessed we are to have: Regina Alouf, Ann PRINCIPAL & HEAD OF SCHOOL Kovats, Kristine Safford and Patrick Patterson Kim Yeaton within our ASSISTANT PRINCIPALS ranks. Julie Frost Christopher Michael These four moms — dubbed The Fabulous Four SCHOOL BOARD — have had their hands and Steve Nagy, Chair hearts in nearly every major John Thomas, Vice Chair Mike McEvoy, Treasurer (Finance) event designed to help Vicki Finnigan, Secretary improve the quality of our Home and School Association’s “Fab Four” (from left): Kim Yeaton, Ann Kovats, Regina Alouf, Kristine Safford ST. ANDREW’S school climate and Rev. Mark White community. Without ever asking, they are here to support our students, Rich Joachim (Strategic Planning) faculty, staff and families with their time, treasures and talents. OUR LADY OF NAZARETH Rev. Msgr. Joseph Lehman, Pastor Their commitment to RCS was exemplified, again, the morning of OUR LADY OF PERPETUAL HELP October 27 during the Junior Class Ring Ceremony. -

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries Atlas of Whether used as a scholarly introduction into Eastern Christian monasticism or researcher’s directory or a travel guide, Alexei Krindatch brings together a fascinating collection of articles, facts, and statistics to comprehensively describe Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States. The careful examina- Atlas of American Orthodox tion of the key features of Orthodox monasteries provides solid academic frame for this book. With enticing verbal and photographic renderings, twenty-three Orthodox monastic communities scattered throughout the United States are brought to life for the reader. This is an essential book for anyone seeking to sample, explore or just better understand Orthodox Christian monastic life. Christian Monasteries Scott Thumma, Ph.D. Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research A truly delightful insight into Orthodox monasticism in the United States. The chapters on the history and tradition of Orthodox monasticism are carefully written to provide the reader with a solid theological understanding. They are then followed by a very human and personal description of the individual US Orthodox monasteries. A good resource for scholars, but also an excellent ‘tour guide’ for those seeking a more personal and intimate experience of monasticism. Thomas Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) This is a fascinating and comprehensive guide to a small but important sector of American religious life. Whether you want to know about the history and theology of Orthodox monasticism or you just want to know what to expect if you visit, the stories, maps, and directories here are invaluable. -

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

Mysticism and Greek Monasticism

Mysticism and Greek Monasticism By JOHANNES RINNE There is reason to assert that Christian mysticism is as old as Christianity itself. In the Pauline epistles, e.g., there are obvious signs of this fact. The later Christian mysticism has, in a high degree, been inspired by these ele- ments and likewise by various corresponding thoughts in the Johannine writings, which traditionally are interpreted from this angle and which have played a central role especially for the Orthodox Church.' In the light of the above-mentioned circumstances, it seems fully natural that there exists, from the very beginning, a clear connection also between mysticism and Christian monasticism. It has been pointed out by certain authors that the role of mystical visions is of essential and decisive significance also as regards the development from the stage of the hermits of the deserts to that form of life which, in the proper sense of the word, is characterised as monastic. There is, generally speaking, no possibility to understand correctly the intentions and the thoughts of the great pioneers of monasticism, unless one takes into account the mystically visionary factors. To this end it is neces- sary, furthermore, to penetrate in an inner, spiritual way, into the holy sym- bolism of the monastic tradition and into the sacred legends of its history.2 In other words, it is necessary to keep constantly in mind the visionary factor and to remember that the pioneers of monastic life, as a rule, are men of which it may be said that they have their conversation in heaven: on the mystical level of vision they converse with the angels as the representatives of the heavenly world and as those organs, by means of which the principles of monastic life are transmitted and given to the men of mystical visions.' The things mentioned above are not merely history. -

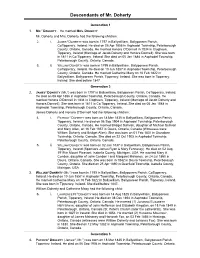

Descendants of Mr. Doherty

Descendants of Mr. Doherty Generation 1 1. MR.1 DOHERTY . He married MRS. DOHERTY. Mr. Doherty and Mrs. Doherty had the following children: 2. i. JAMES2 DOHERTY was born in 1797 in Ballywilliam, Ballyporeen Parish, CoTipperary, Ireland. He died on 08 Apr 1856 in Asphodel Township, Peterborough County, Ontario, Canada. He married Honora O'Donnell in 1834 in Clogheen, Tipperary, Ireland (Marriage of Jacob Doherty and Honora Donnell). She was born in 1811 in Co Tipperary, Ireland. She died on 05 Jan 1888 in Asphodel Township, Peterborough County, Ontario, Canada. 3. ii. WILLIAM DOHERTY was born in 1799 in Ballywilliam, Ballyporeen Parish, CoTipperary, Ireland. He died on 10 Jun 1857 in Asphodel Township, Peterborough County, Ontario, Canada. He married Catherine Maxy on 16 Feb 1822 in Ballywilliam, Ballyporeen Parish, Tipperary, Ireland. She was born in Tipperary, Ireland. She died before 1847. Generation 2 2. JAMES2 DOHERTY (Mr.1) was born in 1797 in Ballywilliam, Ballyporeen Parish, CoTipperary, Ireland. He died on 08 Apr 1856 in Asphodel Township, Peterborough County, Ontario, Canada. He married Honora O'Donnell in 1834 in Clogheen, Tipperary, Ireland (Marriage of Jacob Doherty and Honora Donnell). She was born in 1811 in Co Tipperary, Ireland. She died on 05 Jan 1888 in Asphodel Township, Peterborough County, Ontario, Canada. James Doherty and Honora O'Donnell had the following children: 4. i. PATRICK3 DOHERTY was born on 18 Mar 1835 in Ballywilliam, Ballyporeen Parish, Tipperary, Ireland. He died on 06 Sep 1904 in Asphodel Township, Peterborough County, Ontario, Canada. He married Bridget Sullivan, daughter of Michael Sullivan and Mary Allen, on 16 Feb 1857 in Douro, Ontario, Canada (Witnesses were William Doherty and Bridget Allen). -

Monasticism” and the Vocabulary of Religious Life

What Do We Call IT? New “Monasticism” and the Vocabulary of Religious Life “The letter of the Rule was killing, and the large number of applicants and the high rate of their subsequent leaving shows the dichotomy: men were attracted by what Merton saw in monasticism and what he wrote about it, and turned away by the life as it was dictated by the abbot.” (Edward Rice, The Man in the Sycamore Tree: The good times and hard life of Thomas Merton, p. 77) “Fourth, the new monasticism will be undergirded by deep theological reflection and commitment. by saying that the new monasticism must be undergirded by theological commitment and reflection, I am not saying that right theology will of itself produce a faithful church. A faithful church is marked by the faithful carrying out of the mission given to the church by Jesus Christ, but that mission can be identified only by faithful theology. So, in the new monasticism we must strive simultaneously for a recovery of right belief and right practice.” (Jonathan R. Wilson, Living Faithfully in a Fragmented World: Lessons for the Church from MacIntyre’s After Virtue [1997], pp. 75-76 in a chapter titled “The New Monasticism”) Whether we like the term or not, it is here, probably to stay. “Monasticism.” Is that what it is, new “monasticism”? Is that what we should call it? The problem begins when you try to choose a textbook that covers the history of things. Histories of monasticism only cover the enclosed life. Celtic monasticism prior to Roman adoption is seldom covered. -

Religious Studies Humanities Division We Understand the Study of Religion As a Crucial Element in the Larger Study of Culture and History

Kenyon College Course Catalog 2019-20 Requirements: Religious Studies Humanities Division We understand the study of religion as a crucial element in the larger study of culture and history. We consider the study of religion to be inherently interdisciplinary and a necessary component for intercultural literacy and, as such, essential to the liberal arts curriculum. Our goals include helping students to recognize and examine the important role of religion in history and the contemporary world; to explore the wide variety of religious thought and practice, past and present; to develop methods for the academic study of particular religions and religion in comparative perspective; and to develop the necessary skills to contribute to the ongoing discussion of the nature and role of religion. Since the phenomena that we collectively call "religion" are so varied, it is appropriate that they be studied from a variety of theoretical perspectives and with a variety of methods. The diversity of areas of specialization and approaches to the study of religion among our faculty members ensures the representation of many viewpoints. Our courses investigate the place of religion in various cultures in light of social, political, economic, philosophical, psychological and artistic questions. We encourage religious studies majors to take relevant courses in other departments. The Department of Religious Studies maintains close relationships with interdisciplinary programs such as Asian and Middle East studies, American studies, African diaspora studies, international studies, and women's and gender studies. Our courses require no commitment to a particular faith. However, students of any background, secular or religious, can benefit from the personal questions of meaning and purpose that arise in every area of the subject. -

The Ancient History and the Female Christian Monasticism: Fundamentals and Perspectives

Athens Journal of History - Volume 3, Issue 3 – Pages 235-250 The Ancient History and the Female Christian Monasticism: Fundamentals and Perspectives By Paulo Augusto Tamanini This article aims to discuss about the rediscovery and reinterpretation of the Eastern Monasticism focusing on the Female gender, showing a magnificent area to be explored and that can foment, in a very positive way, a further understanding of the Church's face, carved by time, through the expansion and modes of organization of these groups of women. This article contains three main sessions: understanding the concept of monasticism, desert; a small narrative about the early ascetic/monastic life in the New Testament; Macrina and Mary of Egypt’s monastic life. Introduction The nomenclatures hide a path, and to understand the present questions on the female mystique of the earlier Christian era it is required to revisit the past again. The history of the Church, Philosophy and Theology in accordance to their methodological assumptions, concepts and objectives, give us specific contributions to the enrichment of this comprehensive knowledge, still opened to scientific research. If behind the terminologies there is a construct, a path, a trace was left in the production’s trajectory whereby knowledge could be reached and the interests of research cleared up. Once exposed to reasoning and academic curiosity it may provoke a lively discussion about such an important theme and incite an opening to an issue poorly argued in universities. In the modern regime of historicity, man and woman can now be analysed based on their subjectivities and in the place they belong in the world and not only by "the tests of reason", opening new ways to the researcher to understand them. -

A Mystic Union: Reaching Sufi Women Cynthia A

A Mystic Union: Reaching Sufi Women Cynthia A. Strong Sufism or Islamic mysticism was incorporated into orthodox Islam during the early Middle Ages. Sufi worldview and values, however, can often differ markedly from the faith of other Muslims. In this article Cynthia Strong explains Sufism’s history and attraction and suggests a biblical response. The rhythmic, mnemonic dhikr or chant of Sufi Muslims draws us into a world little known or understood by Westerners. It is a call that differs from the formal Muslim salat, or prayer; a call to a spiritual rather than family lineage; a search for salvation that ends in self-extinction rather than paradise. It is a way of self-discipline in the midst of emotion; a poetry that informs the heart rather than the mind; an ecstatic experience and, for many, a spiritual union that results in supernatural powers. For Sufi Muslims, the Five Pillars and the Shari’ah law can be dry and lifeless. Longing for a direct experience with God and a spiritual advisor who can guide them through the temptations of this world, Sufis belong to a community that brings unique spiritual dimensions to formal Islam. In its vitality, simplicity, aesthetics and worldwide links, Sufism poses a significant challenge to Christian mission. To address it, we must reflect not only on Sufi history and practice but also understand all we are and have in Christ Jesus. Reaching Sufis may urge us to recover some of the spiritual dynamic inherent in the gospel itself. A SHORT HISTORY OF SUFISM Sufism is often described as one of three Sects within Islam along with Sunnis and Shiites. -

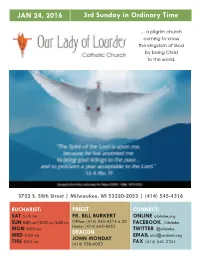

3Rd Sunday in Ordinary Time JAN 24, 2016

JAN 24, 2016 3rd Sunday in Ordinary Time ... a pilgrim church coming to know the kingdom of God by being Christ to the world. 3722 S. 58th Street | Milwaukee, WI 53220-2053 | (414) 545-4316 EUCHARIST: PRIEST CONNECT: SAT 5:00 PM FR. BILL BURKERT ONLINE ololmke.org SUN 8:00 AM /10:30 AM /6:00 PM Office: (414) 545-4316 x 20 FACEBOOK /ololmke Home: (414) 645-8053 MON AM TWITTER 8:00 DEACON @ololmke WED AM EMAIL 9:30 JOHN MONDAY [email protected] THU 8:00 AM FAX (414) 541-2251 (414) 550-6053 FINANCIAL STEWARDSHIP UPDATE COMMUNITY LIFE Parish Support - January 4-10, 2016 Stewardship Offering (Envelopes/Electronic) ...................................... $12,245.50 In Memoriam Offertory ........................................................................................................... $674.36 In loving memory of Mary Jean and William McVeigh Budget Updates Fiscal Year: July 1, 2015-June 30, 2016 From Contributions Received ............................................................................ $408,029.02 Kathleen Schmid Contribution Budget ................................................................................. $417,400.00 Mary Lamping Difference as of 1/10/16 ............................................................ ($9,370.98) In loving memory of Operating Income .................................................................................... $567,768.86 Rick Schmus Operating Expenses ................................................................................ $533,901.08 From Balance as of 12/31/15 ............................................................. -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2009 Issue 4 CoJS Newsletter • March 2009 • Issue 4 Centre for Jaina Studies' Members _____________________________________________________________________ SOAS MEMBERS EXTERNAL MEMBERS Honorary President Paul Dundas Professor J Clifford Wright (University of Edinburgh) Vedic, Classical Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit Senior Lecturer in Sanskrit language and literature; comparative philology Dr William Johnson (University of Cardiff) Chair/Director of the Centre Jainism; Indian religion; Sanskrit Indian Dr Peter Flügel Epic; Classical Indian religions; Sanskrit drama. Jainism; Religion and society in South Asia; Anthropology of religion; Religion ASSOCIATE MEMBERS and law; South Asian diaspora. John Guy Professor Lawrence A. Babb (Metropolitan Mueum of Art) Dr Daud Ali (Amherst College) History of medieval South India; Chola Professor Phyllis Granoff courtly culture in early medieval India Professor Nalini Balbir (Yale University) (Sorbonne Nouvelle) Dr Crispin Branfoot Dr Julia Hegewald Hindu, Buddhist and Jain Architecture, Dr Piotr Balcerowicz (University of Manchester) Sculpture and Painting; Pilgrimage and (University of Warsaw) Sacred Geography, Archaeology and Professor Rishabh Chandra Jain Material Religion; South India Nick Barnard (Muzaffarpur University) (Victoria and Albert Museum) Professor Ian Brown Professor Padmanabh S. Jaini The modern economic and political Professor Satya Ranjan Banerjee (UC Berkeley) history of South East Asia; the economic (University of Kolkata) -

Retreat 1 Retreat 2

Retreat 1 PRE-READING ● Invitation to a Journey: A Road Map for Spiritual Formation, M. Robert Mulholland ● Thirsty For God: A Brief History of Christian Spirituality, Bradley Holt REQUIRED – TRANSFORMING RESOURCES (CONTAINS TEACHINGS FROM THIS RETREAT) ● Invitation to Retreat, (one chapter and practice/week), Ruth Haley Barton ● Life Together in Christ (Introduction & Chapters 1 & 2), Ruth Haley Barton ● Sacred Rhythms (Introduction & Chapter 1), Ruth Haley Barton ● Strengthening the Soul of Your Leadership (Introduction & Chapter 1), Ruth Haley Barton REQUIRED READINGS – OTHER AUTHORS ● Befriending Our Desires, Philip Sheldrake ● The Holy Longing, Ronald Rolheiser ● Life Together, Dietrich Bonhoeffer ● Rest in the Storm, Kirk Byron Jones RECOMMENDED READING ● Concerning the Inner Life, Evelyn Underhill ● Holy Listening, Margaret Guenther ● Imitation of Christ, Thomas a Kempis and Edythe Draper ● Leaving Church, Barbara Brown Taylor ● The Making of an Ordinary Saint: My Journey from Frustration to Joy with the Spiritual Disciplines, Nathan Foster ● Spirit of the Disciplines, Dallas Willard ● Wilderness Time, Emilie Griffin Retreat 2 REQUIRED – TRANSFORMING RESOURCES (CONTAINS TEACHINGS FROM THIS RETREAT) ● Invitation to Solitude and Silence, Ruth Haley Barton (one chapter and practice/week) ● Sacred Rhythms (Chapter 2), Ruth Haley Barton ● Life Together in Christ (Chapters 1-4), Ruth Haley Barton REQUIRED READINGS – OTHER AUTHORS ● The Way of the Heart, Henri Nouwen ● Everything Belongs, Richard Rohr ● Interior Castle, Teresa of Avila* CHOOSE ONE: ● Poustinia: Encountering God in Silence, Solitude and Prayer, Catherine Doherty ● Joy Unspeakable: Contemplative Practices of the Black Church, Barbara A. Holmes *An excellent companion for Interior Castle is Entering Teresa of Avila’s Interior Castle: A Reader’s Companion, Gillian T.W.