Mushrooms in the Russian Far East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOUR SEASONS Moscow Tel: NOT Setemail: [email protected]

FOUR SEASONS Moscow Tel: NOT_SETEmail: [email protected] OPENING DATE: October 2014 GENERAL MANAGER: Max Musto Physical Features Total Number of Rooms: 180 • Guest Rooms: 141 • Suites: 39 Design Aesthetic: • Restored 1930s exterior with unique assymetric design, with a glass-topped atrium at the building's centre • Dramatic, clean-lined interiors Architect: • Alexei Shchusev (original building) Interior Designer(s): • Richmond International Location: • Overlooking Manezhnaya Square, just steps from Red Square, the Kremlin, the Bolshoi Theatre, St. Basil's Cathedral and GUM shopping complex Amnis Spa Number of Treatment Rooms: 14 • Includes three couples suites Signature Treatments: • Modern interpretation of the traditional Russian banya experience Special Facilities: • Men's and women's lounges, hair salon and nail bar, indoor pool and spa cafe Dining Restaurant: Quadrum • Cuisine: Italian • Seating: 89 Restaurant: Bystro • Cuisine: All day dining; Russian Nordic dinner • Seating: 106 1 Restaurant: Amnis Café • Cuisine: Healthy refreshments served poolside • Seating: 15 Lounge: Moskovsky Bar • Cuisine: Zakuski (Russian tapas), crudo and international bar snacks • Seating: 88 Lounge: Silk Lounge • Cuisine: Cocktails, light fare, afternoon tea, French pastries • Seating: 68 Recreation On-site Activities Pools: 1 indoor pool • 148 sq. m / 1,593 sq. ft. • 2 m / 6.56 ft. deep • Special Features: no-fog glass topped atrium Fitness Facilities: • 198 sq. m / 2,131 sq. ft. • Weight training, studio classes, certified personal trainers on request • Equipment: Technogym For Families • Complimentary amenities for children • Babysitting services available upon request • Pet-friendly Meeting Rooms Total Size: 15,123 sq. ft. / 1,405 sq. m Largest Ballroom: 5,703 sq. ft. / 530 sq. m Second Banquet Room: 2,583 sq ft / 240 sq m Additional Meeting Rooms: 5 2 PRESS CONTACTS Natalia Lapshina Director of Public Relations and Communications 2, Okhotny Ryad Moscow Russia [email protected] +7 499 277 7130 3. -

Bur¯Aq Depicted As Amanita Muscaria in a 15Th Century Timurid-Illuminated Manuscript?

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3(2), pp. 133–141 (2019) DOI: 10.1556/2054.2019.023 First published online September 24, 2019 Bur¯aq depicted as Amanita muscaria in a 15th century Timurid-illuminated manuscript? ALAN PIPER* Independent Scholar, Newham, London, UK (Received: May 8, 2019; accepted: August 2, 2019) A series of illustrations in a 15th century Timurid manuscript record the mi’raj, the ascent through the seven heavens by Mohammed, the Prophet of Islam. Several of the illustrations depict Bur¯aq, the fabulous creature by means of which Mohammed achieves his ascent, with distinctive features of the Amanita muscaria mushroom. A. muscaria or “fly agaric” is a psychoactive mushroom used by Siberian shamans to enter the spirit world for the purposes of conversing with spirits or diagnosing and curing disease. Using an interdisciplinary approach, the author explores the routes by which Bur¯aq could have come to be depicted in this manuscript with the characteristics of a psychoactive fungus, when any suggestion that the Prophet might have had recourse to a drug to accomplish his spirit journey would be anathema to orthodox Islam. There is no suggestion that Mohammad’s night journey (isra) or ascent (mi’raj) was accomplished under the influence of a psychoactive mushroom or plant. Keywords: Mi’raj, Timurid, Central Asia, shamanism, Siberia, Amanita muscaria CULTURAL CONTEXT Bur¯aq depicted as Amanita muscaria in the mi’raj manscript The mi’raj manuscript In the Muslim tradition, the mi’raj was preceded by the isra or “Night Journey” during which Mohammed traveled An illustrated manuscript depicting, in a series of miniatures, overnight from Mecca to Jerusalem by means of a fabulous thesuccessivestagesofthemi’raj, the miraculous ascent of beast called Bur¯aq. -

Field Guide to Common Macrofungi in Eastern Forests and Their Ecosystem Functions

United States Department of Field Guide to Agriculture Common Macrofungi Forest Service in Eastern Forests Northern Research Station and Their Ecosystem General Technical Report NRS-79 Functions Michael E. Ostry Neil A. Anderson Joseph G. O’Brien Cover Photos Front: Morel, Morchella esculenta. Photo by Neil A. Anderson, University of Minnesota. Back: Bear’s Head Tooth, Hericium coralloides. Photo by Michael E. Ostry, U.S. Forest Service. The Authors MICHAEL E. OSTRY, research plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station, St. Paul, MN NEIL A. ANDERSON, professor emeritus, University of Minnesota, Department of Plant Pathology, St. Paul, MN JOSEPH G. O’BRIEN, plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, St. Paul, MN Manuscript received for publication 23 April 2010 Published by: For additional copies: U.S. FOREST SERVICE U.S. Forest Service 11 CAMPUS BLVD SUITE 200 Publications Distribution NEWTOWN SQUARE PA 19073 359 Main Road Delaware, OH 43015-8640 April 2011 Fax: (740)368-0152 Visit our homepage at: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/ CONTENTS Introduction: About this Guide 1 Mushroom Basics 2 Aspen-Birch Ecosystem Mycorrhizal On the ground associated with tree roots Fly Agaric Amanita muscaria 8 Destroying Angel Amanita virosa, A. verna, A. bisporigera 9 The Omnipresent Laccaria Laccaria bicolor 10 Aspen Bolete Leccinum aurantiacum, L. insigne 11 Birch Bolete Leccinum scabrum 12 Saprophytic Litter and Wood Decay On wood Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus populinus (P. ostreatus) 13 Artist’s Conk Ganoderma applanatum -

A Taste of Teaneck

.."' Ill • Ill INTRODUCTION In honor of our centennial year by Dorothy Belle Pollack A cookbook is presented here We offer you this recipe book Pl Whether or not you know how to cook Well, here we are, with recipes! Some are simple some are not Have fun; enjoy! We aim to please. Some are cold and some are hot If you love to eat or want to diet We've gathered for you many a dish, The least you can do, my dears, is try it. - From meats and veggies to salads and fish. Lillian D. Krugman - And you will find a true variety; - So cook and eat unto satiety! - - - Printed in U.S.A. by flarecorp. 2884 nostrand avenue • brooklyn, new york 11229 (718) 258-8860 Fax (718) 252-5568 • • SUBSTITUTIONS AND EQUIVALENTS When A Recipe Calls For You Will Need 2 Tbsps. fat 1 oz. 1 cup fat 112 lb. - 2 cups fat 1 lb. 2 cups or 4 sticks butter 1 lb. 2 cups cottage cheese 1 lb. 2 cups whipped cream 1 cup heavy sweet cream 3 cups whipped cream 1 cup evaporated milk - 4 cups shredded American Cheese 1 lb. Table 1 cup crumbled Blue cheese V4 lb. 1 cup egg whites 8-10 whites of 1 cup egg yolks 12-14 yolks - 2 cups sugar 1 lb. Contents 21/2 cups packed brown sugar 1 lb. 3112" cups powdered sugar 1 lb. 4 cups sifted-all purpose flour 1 lb. 4112 cups sifted cake flour 1 lb. - Appetizers ..... .... 1 3% cups unsifted whole wheat flour 1 lb. -

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

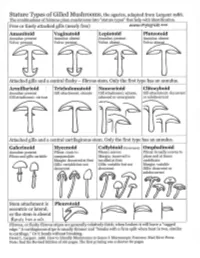

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

CZECH MYCOLOGY Publication of the Czech Scientific Society for Mycology

CZECH MYCOLOGY Publication of the Czech Scientific Society for Mycology Volume 57 August 2005 Number 1-2 Central European genera of the Boletaceae and Suillaceae, with notes on their anatomical characters Jo s e f Š u t a r a Prosetická 239, 415 01 Tbplice, Czech Republic Šutara J. (2005): Central European genera of the Boletaceae and Suillaceae, with notes on their anatomical characters. - Czech Mycol. 57: 1-50. A taxonomic survey of Central European genera of the families Boletaceae and Suillaceae with tubular hymenophores, including the lamellate Phylloporus, is presented. Questions concerning the delimitation of the bolete genera are discussed. Descriptions and keys to the families and genera are based predominantly on anatomical characters of the carpophores. Attention is also paid to peripheral layers of stipe tissue, whose anatomical structure has not been sufficiently studied. The study of these layers, above all of the caulohymenium and the lateral stipe stratum, can provide information important for a better understanding of relationships between taxonomic groups in these families. The presence (or absence) of the caulohymenium with spore-bearing caulobasidia on the stipe surface is here considered as a significant ge neric character of boletes. A new combination, Pseudoboletus astraeicola (Imazeki) Šutara, is proposed. Key words: Boletaceae, Suillaceae, generic taxonomy, anatomical characters. Šutara J. (2005): Středoevropské rody čeledí Boletaceae a Suillaceae, s poznámka mi k jejich anatomickým znakům. - Czech Mycol. 57: 1-50. Je předložen taxonomický přehled středoevropských rodů čeledí Boletaceae a. SuiUaceae s rourko- vitým hymenoforem, včetně rodu Phylloporus s lupeny. Jsou diskutovány otázky týkající se vymezení hřibovitých rodů. Popisy a klíče k čeledím a rodům jsou založeny převážně na anatomických znacích plodnic. -

THE SUN, the MOON and FIRMAMENT in CHUKCHI MYTHOLOGY and on the RELATIONS of CELESTIAL BODIES and SACRIFICE Ülo Siimets

THE SUN, THE MOON AND FIRMAMENT IN CHUKCHI MYTHOLOGY AND ON THE RELATIONS OF CELESTIAL BODIES AND SACRIFICE Ülo Siimets Abstract This article gives a brief overview of the most common Chukchi myths, notions and beliefs related to celestial bodies at the end of the 19th and during the 20th century. The firmament of Chukchi world view is connected with their main source of subsistence – reindeer herding. Chukchis are one of the very few Siberian indigenous people who have preserved their religion. Similarly to many other nations, the peoples of the Far North as well as Chukchis personify the Sun, the Moon and stars. The article also points out the similarities between Chukchi notions and these of other peoples. Till now Chukchi reindeer herders seek the supposed help or influence of a constellation or planet when making important sacrifices (for example, offering sacrifices in a full moon). According to the Chukchi religion the most important celestial character is the Sun. It is spoken of as an individual being (vaúrgún). In addition to the Sun, the Creator, Dawn, Zenith, Midday and the North Star also belong to the ranks of special (superior) beings. The Moon in Chukchi mythology is a man and a being in one person. It is as the ketlja (evil spirit) of the Sun. Chukchi myths about several stars (such as the North Star and Betelgeuse) resemble to a great extent these of other peoples. Keywords: astral mythology, the Moon, sacrifices, reindeer herding, the Sun, celestial bodies, Chukchi religion, constellations. The interdependence of the Earth and celestial as well as weather phenomena has a special meaning for mankind for it is the co-exist- ence of the Sun and Moon, day and night, wind, rainfall and soil that creates life and warmth and provides the daily bread. -

To View Online Click Here

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® The Baltic Capitals & St. Petersburg 2022 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. Enhanced! The Baltic Capitals & St. Petersburg itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: What I love about the little town of Harmi, Estonia, is that it has a lot of heart. Its residents came together to save their local school, and now it’s a thriving hub for community events. Harmi is a new partner of our Grand Circle Foundation, and you’ll live a Day in the Life here, visiting the school and a family farm, and sharing a farm-to-table lunch with our hosts. I love the outdoors and I love art, so my walk in the woods with O.A.T. Trip Experience Leader Inese turned into something extraordinary when she led me along the path called the “Witches Hill” in Lithuania. It’s populated by 80 wooden sculptures of witches, faeries, and spirits that derive from old pagan beliefs. You’ll go there, too (and I bet you’ll be as surprised as I was to learn how prevalent those pagan practices still are.) I was also surprised—and saddened—to learn how terribly the Baltic people were persecuted during the Soviet era. -

FRIDAY, JANUARY 25, 2019 Phoenix Art Museum EVENING EVENTS

FRIDAY, JANUARY 25, 2019 Phoenix Art Museum EVENING EVENTS 6:30 pm Cocktails | Greenbaum Lobby 7:30 pm The Making of The Firebird | Great Hall 8:00 pm Dinner and Dancing | Great Hall HONORARY CHAIRS Billie Jo & Judd Herberger The Phoenix-Scottsdale landscape was changed forever Chair: Adrienne Schiffner in 1948 when Bob and Katherine “Kax” Herberger moved Co-Chairs: Barbara Ottosen & Daryl Weil their young family here from Minnesota. Soon, the couple began giving the growing city what it needed to Gala Committee be vibrant: Art. Ellen Andres-Schneider, Joan Berry, Salvador Bretts- “Kax” was an artist and collector. She and Bob wanted Jamison, Carol Clemmensen, Jacquie Dorrance, Mary their sons, Gary and Judd, to enjoy the arts, and Ehret, Barbara Fenzl, Susie Fowls, Stephanie Goodman, encouraged their support of arts groups. Molly Greene, Kate Groves, Linda Herold, Gwen Hillis, Keryl Koffler, Jan Lewis, Sharron Lewis, Linda Lindgren, Over the past 70 years, the Herberger family has Miranda Lumer, Betty McRae, Janet Melamed, Richard launched and supported many of the Valley’s arts Monast, Doris Ong, Camerone Parker McCulloch, Carol organizations including, the Herberger Theater Schilling, Leslie Smith, Colleen Steinberg, Ellen Stiteler, Center, Phoenix Art Museum, Phoenix Theatre, Valley Vicki Vaughn, Ruth & John Waddell, Nancy White Shakespeare Festival, Arizona Opera, The Phoenix Symphony, Valley Youth Theatre, Childsplay, and our own Artistic Director: Ib Andersen Ballet Arizona. In addition, Billie Jo and Judd have been Executive Director: Samantha Turner major supporters of the Scottsdale Waterfront’s Canal Convergence, Release the Fear, and Kids Read USA. Development Staff: Jami Kozemczak, Natalie Salvione, Elyse Salisz and Ellen Bialek “Mother taught us that involving young people in the arts is most important,” says Judd. -

Refugees of Former Union Slowly Adopt

ter of 1994. The two provider focus groups included 16 employees from Sacramento agencies that provide ser- vices to individuals from the FSU. The six refugee focus groups included 35 adult refugees (mostly female) se- lected by six local agencies. We wanted people who had come to the United States after the fall of the Com- munist regime and who were knowl- edgeable of other people in the refugee community. In addition, a panel of key members of the FSU refugee commu- nity, selected by the researchers, pro- vided more than 20 consultations dur- ing the study. A matrix of consistent responses obtained among the focus groups was used to assess the validity of the data. Additional information was acquired during visits to homes of refugees, visits to newly established Food preparation can be a celebration for many women from the former Soviet Union, Russian grocery stores and participa- who enjoy their role as gatekeepers of dietary traditions. tion in religious celebrations (Romero- Gwynn et al. 1994). FSU refugees in Sacramento Refugees of former Soviet Most refugees from the FSU who settled in Sacramento prior to 1994 came from farming communities or small Union slowly adopt US. diet towns in the Slavic states or from the former Russian Central Asia region. The Eunice Romero-Gwynn o Yvonne Nicholson a Douglas Gwynn migration pattern to other sites in Cali- Holly Raynard o Nancy Kors a Peggy Agron o Jan Fleming fornia appears to be different. Lakshmi Sreenivasan The typical refugee family in Sacra- mento is large and often extended. It consists of a husband, wife, children The diet of refugees from the In the past decade, California has ex- (as many as 12 reported) and, very of- former Soviet Union living in perienced a post-Cold War influx of ten, parents of one or both spouses. -

Cultural Eating Patterns of Germany Erika Gaye, Erin Nargi, Staci Owens, Mitchell Remond Geography Geographic Overview

Cultural Eating Patterns of Germany Erika Gaye, Erin Nargi, Staci Owens, Mitchell Remond Geography Geographic Overview: ● Located in west-central Europe ● Surrounded by France, Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg to the West; Switzerland and Austria to the South; Poland and Czech Republic to the East and Denmark to the North ● Diverse landscape : ○ Plains ○ Valleys ○ Marshland ○ Wooded forests ○ Mountains ○ Sea towns Historical Overview Early History ● Hops grown in N. Germany during 13th century ● 16th century - Brewing beer became popular ○ Brewed in accordance with Deutsche Reinheitsgebot - German Law of Purity ■ Water, hops, malt ● 17th century - Potato introduced by King Frederick II ○ Staple food in modern Germany World War I ● Outbreak of war in 1914 ○ Decreased imports - blockaded ports ○ Less men farming; needed for war effort ● Introduction of rationing ○ Most food went to individuals contributing to war effort ○ Potatoes were main source of food ■ Eventually reduced to eating swedes (Cattle Fodder) World War II ● Outbreak of war in 1939 ● Volkornbrot - dark wholemeal bread ○ Bran and germ kept in flour ■ Couldn’t be processed during war ○ Pumpernickel bread = most popular ● Rationing continued ○ Even more strict than WWI ○ Military took most ○ Farmers would under report to keep more for themselves Division ● After losing WWII, Germany’s culture was divided (1949) ○ East Germany vs. West Germany ○ Berlin Wall goes up in 1961 ● Division brought the emergence of different cooking styles ○ East Germany (German Democratic Republic) -

322-3-Cultural Identity in Russia

CS 322 Peoples and Cultures of the Circumpolar World II Module 3 Changes in Expressions of Cultural Identity in Northwest Russia, Siberia and the Far East Contents Course objectives 1 Introduction 2 Indigenous and non-indigenous northern identities 4 The impact of media on indigenous peoples 7 Expression of identity and self-determination through media 9 Expression of identity and self-determination through literary and visual arts 12 Family, education and recreation as social institutions for self-determination 16 Indigenous families: the impact of assimilation processes 18 Education systems: indigenous concerns vs. educational practices 19 Recreation 22 Glossary of terms 23 Literature 24 Course objectives Whereas the changes in expressions of cultural identity in the North American Arctic was the main topic of the previous module, this module discusses the changes in expressions of cultural self-determination of the indigenous peoples of the Russian Arctic; often described as Northwest Russia, Siberia and the Russian Far East.1 Complex issues in relation to culture, identity and self-determination were discussed in detail in the first module of this course, which could be seen as an introduction to explain the theoretical background which 1 The Russian Far Eastern Federal District includes all the areas from Vladivostok and Primorskiy Krai right up through Khabarovsk, Amur, Sakha, Magadan, Kamchatka before reaching Chukotka in the north (Sakhalin and Kamchatka further east are included as well). University of the Arctic – CS 322 1 CS 322 Peoples and Cultures of the Circumpolar World II subsequently will be applied in this, the previous and the next module where the case studies of the different regions will be discussed.