Adaptive Cruise Control: Hybrid, Distributed, and Now Formally

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vehicle Technical Information Guide for Cruise Control

Vehicle Technical Information Guide For Cruise Control Model Years: 1996-2009 FOR PRE 1996 VEHICLE INFORMATION, REQUEST FORM #4429 TECHNICAL SERVICE PHONE: (910) 277-1828 TECHNICAL SERVICE FAX: (910) 276-3759 WEB: WWW.ROSTRA.COM FORM #4428, REV. L, 02-17-09 WARNING: The information presented in this manual has been carefully compiled through actual vehicle testing and manufacturers service manual research and to the best of our ability is accurate. However, we do not warrant the accuracy of this infor- mation against changes in vehicle design, the use or misuse of this information or typographical errors. It is the responsibility of installer to verify the signal and color on the wire attachments prior to and after the installation of the cruise control to assure proper operation of the cruise control and the vehicle through a road test. We do not accept any responsibility for damage to the vehicle or injury to its occupants caused by the use of this information. Connection to the incorrect wires could cause cruise control or vehicle malfunctions and component damage. These conditions can cause a major risk while driving for you, your passengers and other motorists, exposing all of you to the risk of acci- dent and injury. Any installation of a cruise control on a vehicle that does not have clearance at the throttle for lost motion or may have interference by other parts must have the cruise control cable attached to the WARNING: accelerator pedal for obvious safety reasons. Any installation of a cruise control on a vehicle with an accelerator pedal activated switch for emissions or transmission shifting must have the cruise control cable attached to the accelerator pedal for proper vehicle operation. -

Design and Validation of Safety Cruise Control System for Automobiles

DESIGN AND VALIDATION OF SAFETY CRUISE CONTROL SYSTEM FOR AUTOMOBILES Jagannath Aghav and Ashwin Tumma Department of Computer Engineering and Information Technology, College of Engineering Pune, Shivajinagar, Pune, India {jva.comp, tummaak08.comp}@coep.ac.in ABSTRACT In light of the recent humongous growth of the human population worldwide, there has also been a voluminous and uncontrolled growth of vehicles, which has consequently increased the number of road accidents to a large extent. In lieu of a solution to the above mentioned issue, our system is an attempt to mitigate the same using synchronous programming language. The aim is to develop a safety crash warning system that will address the rear end crashes and also take over the controlling of the vehicle when the threat is at a very high level. Adapting according to the environmental conditions is also a prominent feature of the system. Safety System provides warnings to drivers to assist in avoiding rear-end crashes with other vehicles. Initially the system provides a low level alarm and as the severity of the threat increases the level of warnings or alerts also rises. At the highest level of threat, the system enters in a Cruise Control Mode, wherein the system controls the speed of the vehicle by controlling the engine throttle and if permitted, the brake system of the vehicle. We focus on this crash area as it has a very high percentage of the crash-related fatalities. To prove the feasibility, robustness and reliability of the system, we have also proved some of the properties of the system using temporal logic along with a reference implementation in ESTEREL. -

Adaptive Cruise Control System Evaluation According to Human Driving Behavior Characteristics

actuators Article Adaptive Cruise Control System Evaluation According to Human Driving Behavior Characteristics Lin Liu 1, Qiang Zhang 2, Rui Liu 3, Xichan Zhu 1,* and Zhixiong Ma 1 1 School of Automotive Studies, Tongji University, Shanghai 201804, China; [email protected] (L.L.); [email protected] (Z.M.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Vehicle NVH and Safety Technology, Chongqing 401122, China; [email protected] 3 School of Automobile, Chang’an University, Xi’an 710064, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: With the rapid and wide implementation of adaptive cruise control system (ACC), the testing and evaluation method becomes an important question. Based on the human driver behavior characteristics extracted from naturalistic driving studies (NDS), this paper proposed the testing and evaluation method for ACC systems, which considers safety and human-like at the same time. Firstly, usage scenarios of ACC systems are defined and test scenarios are extracted and categorized as safety test scenarios and human-like test scenarios according to the collision likelihood. Then, the characteristic of human driving behavior is analyzed in terms of time to collision and acceleration distribution extracted from NDS. According to the dynamic parameters distribution probability, the driving behavior is divided into safe, critical, and dangerous behavior regarding safety and aggressive and normal behavior regarding human-like according to different quantiles. Then, the baselines for evaluation are designed and the weights of different scenarios are determined according to exposure frequency, resulting in a comprehensive evaluation method. Finally, an ACC system is Citation: Liu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, R.; tested in the selected test scenarios and evaluated with the proposed method. -

Adaptive Cruise Control System Overview

5th Meeting of the U.S. Software System Safety Working Group April 12th-14th 2005 @ Anaheim, California USA Adaptive Cruise Control System Overview 1 Introduction Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) is an automotive feature that allows a vehicle's cruise control system to adapt the vehicle's speed to the traffic environment. A radar system attached to the front of the vehicle is used to detect whether slower moving vehicles are in the ACC vehicle's path. If a slower moving vehicle is detected, the ACC system will slow the vehicle down and control the clearance, or time gap, between the ACC vehicle and the forward vehicle. If the system detects that the forward vehicle is no longer in the ACC vehicle's path, the ACC system will accelerate the vehicle back to its set cruise control speed. This operation allows the ACC vehicle to autonomously slow down and speed up with traffic without intervention from the driver. The method by which the ACC vehicle's speed is controlled is via engine throttle control and limited brake operation. 2 Definitions and Physical Overview clearance ACC Vehicle (time gap = clearance / vehicle speed) Target Vehicle Forward Vehicle Figure 1 – ACC Vehicle Relationships 1 2.1 Definitions Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) – An enhancement to a conventional cruise control system which allows the ACC vehicle to follow a forward vehicle at an appropriate distance. ACC vehicle – the subject vehicle equipped with the ACC system. active brake control – a function which causes application of the brakes without driver application of the brake pedal. clearance – distance from the forward vehicle's trailing surface to the ACC vehicle's leading surface. -

ELITE DIGITAL SPEEDOMETER Installation Tips

INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS ELITE DIGITAL SPEEDOMETER 2650-1951-77 Models 6789-CB, 6789-PH, 6789-SC, 6789-UL QUESTIONS: If after completely reading these instructions you have questions regarding the operation or installation of your instrument(s), please contact AutoMeter Technical Service at 866-248-6357. You may also email us at [email protected]. Additional information can also be found at http://www.autometer.com. General Information This instrument utilizes a single LCD to display odometer and two trip odometer mileages. Press the Trip (Right) button on the dial window to cycle between odometer, Trip 1, and Trip 2 displays on the LCD. Pressing and holding the Trip button for more than 2 seconds while viewing either Trip display will reset the trip currently being displayed. The odometer cannot be reset. NOTE: The odometer on the speedometer portion of this instrument will show some mileage less than 5 miles (8km). This is a result of factory testing to ensure optimum quality. TIP: AutoMeter always recommends performing the calibration process for best speedometer accuracy. Speedometer Senders: The electronic speedometer in this instrument is designed to operate with an electrical speed sensor. The speed sensor signal range must be between 500 and 400,000 pulses/mile (310 and 248,500 pulses/km). Any speed sensor or electronic module that meets the following two conditions can be used: 1. Pulse rate generated is proportional to vehicle speed. 2. Output voltage within the ranges listed below: a. Hall effect sender, 3 wire (5 to 16V) b. Sine wave generator, 2-wire (1.4 VAC min.) c. -

Driver Assistance Technologies

VEHICLE SHOPPER’S GUIDE Driver Assistance Technologies What is Driver Assistance Technology? Driver assistance technologies can warn your teenage driver that there is a car in their blind spot when switching lanes; apply the brakes for you if a child from your neighborhood darts into the street; or warn you if you are about to back into another car in the grocery store parking lot. But these technologies don’t drive your car; all vehicles still need a human driver behind the wheel. NHTSA created this guide to make today’s driver assistance technologies easy to understand for all drivers. Assisting With Backing Up & Parking Maintaining Safe Distance Rear Automatic Braking Traffic Jam Assist Applies your vehicle’s brakes Automatically accelerates for you to prevent a rear and brakes your vehicle along collision when backing up. with the flow of traffic, and keeps your vehicle between lane markings — even curves. Backup Camera Highway Pilot Provides you with a clear view Maintains your vehicle’s lane directly behind your vehicle. position and a determined following distance from the vehicle in front by automatically accelerating and braking as needed. Rear Cross Traffic Alert Warns you of a potential rear Adaptive Cruise Control collision that may be outside Automatically adjusts your the view of your backup vehicle’s speed to maintain a camera. set following distance from the vehicle in front. Preventing Forward Collisions Navigating Lanes Safely Forward Collision Warning Lane Departure Warning Detects and warns you of a Detects and warns that potential forward collision. your vehicle is drifting over the lane markings. -

Cruise Control and Air Bags

Cruise Control May use intake manifold vacuum to pull open the throttle. May use electric motor to open throttle. Computer controlled Needs driver input, vehicle speed input, and safety release features. Solenoids will add or remove engine vacuum to the throttle servo Driver InputVehicle Speed Input Computer Control Safety Release Cruise Control Looks at vehicle speed Requires input from driver Set Resume Coast Cruise Control Will be designed to release throttle if there is any malfunction ANY loss of power will release Vacuum Port Open all servo vacuum when OFF and turn OFF the Cruise Control Computer grounds one solenoid to increase or decrease vehicle speed Vacuum Ports Closed when Off Computer grounds one solenoid to increase or decrease vehicle speed Diagnose Cruise Control Check input from brake/clutch switch (very common fault on older cars) Ensure good vacuum to control servo Check input from cruise control switch Check input from vehicle speed sensor Check voltage at cruise control servo Cruise Control Switch Where is the cruise control switch located? Steering Column What is dangerous about removing the Horn Pad? Air Bags Before you remove the steering wheel you must disarm the air bag…. ….or you might get a very flat nose …. …………….or worse……... Supplemental Restraint System Must be disabled prior to removing the air bag module Designed to fire after loss of battery power DO NOT SAVE the memory if procedure says to remove a battery cable Supplemental Restraint System If deployed: Sodium Hydroxide powder is irritating to skin and lungs Clock spring connector likely needs replacing due to power surge Clock-Spring Coil Follow specific procedure for centering clock spring coil. -

ADVANCED DRIVER ASSISTANCE TECHNOLOGY NAMES AAA’S Recommendation for Common Naming of Advanced Safety Systems

JANUARY 2019 ADVANCED DRIVER ASSISTANCE TECHNOLOGY NAMES AAA’s recommendation for common naming of advanced safety systems NewsRoom.AAA.com Advanced Driver Assistance Technology Names (this page intentionally left blank) © 2019 American Automobile Association, Inc. 2 Advanced Driver Assistance Technology Names Abstract Advanced Driver Assistance Systems have become increasingly prevalent on new vehicles. In fact, at least one ADAS feature is available on 92.7% of new vehicles available in the U.S. as of May 2018.1 Not only are these advanced driver assistance systems within financial reach of many new car consumers (about $1,950 for the average ADAS bundle2), they also have the potential to avoid or mitigate the severity of a crash. However, the terminology used to describe them varies widely and often seems to prioritize marketing over clarity. The lack of standardized names for automotive systems adds confusion for motorists when researching and using advanced safety systems. The intent of this paper is to create a dialog with the automotive industry, safety organizations and legislators about the need for common naming for advanced driver assistance systems. Within this report, AAA is proposing a set of standardized technology names for use in describing advanced safety systems. AAA acknowledges that this is a dynamic environment, and that further input from stakeholders and consumer research will further refine this recommendation. To date, automakers have devised their own branded technology names which, for example, has resulted in twenty unique names for adaptive cruise control and nineteen different names for lane keeping assistance (section 3.2) alone. A selection of these names is shown in Figure 1. -

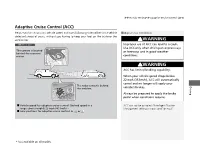

Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC)

uuHonda Sensing®uAdaptive Cruise Control (ACC) Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) Helps maintain a constant vehicle speed and a set following-interval behind a vehicle 1Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) detected ahead of yours, without you having to keep your foot on the brake or the accelerator. 3WARNING When to use Improper use of ACC can lead to a crash. Use ACC only when driving on expressways The camera is located or freeways and in good weather behind the rearview mirror. conditions. 3WARNING ACC has limited braking capability. When your vehicle speed drops below 22 mph (35 km/h), ACC will automatically cancel and no longer will apply your The radar sensor is behind Driving the emblem. vehicle's brakes. Always be prepared to apply the brake pedal when conditions require. ■ Vehicle speed for adaptive cruise control: Desired speed in a ACC can not be activated if Intelligent Traction range above roughly 25 mph (40 km/h) ~ Management setting is snow, sand* or mud* . ■ Gear positions for adaptive cruise control: In (D or (S * Not available on all models uuHonda Sensing®uAdaptive Cruise Control (ACC) ■ How to activate the system 1Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) How to use Important Reminder ACC is on in the driver As with any system, there are limits to ACC. Use the information interface. brake pedal whenever necessary, and always keep a Adaptive cruise control is safe interval between your vehicle and other vehicles. ready to use. You can read about handling information for the camera equipped with this system. The radar sensor for ACC is shared with the Collision Mitigation Braking SystemTM (CMBSTM ). -

2020 Cadillac CT6 Super Cruise Personalization Guide

2020 CT6 SUPER CRUISE™ Convenience & Personalization Guide cadillac.com Review this guide for an overview of the Super Cruise™ driver assistance feature in your CT6. Even Certain restrictions, precautions and safety while using Super Cruise, always pay attention while driving and do not use a hand-held device. Visit procedures apply to your vehicle. Please read cadillacsupercruise.com for compatible highways and more information. Operation requires active your Owner’s Manual for complete instructions. OnStar plan, active Wi-Fi hotspot, working electrical system, cell reception, and GPS signal. SUPER CRUISE OVERVIEW Adaptive Cruise Super Cruise/Driver Steering Adaptive Cruise Driver Control–Advanced/ Assistance Page Wheel Light Control–Advanced Super Cruise Attention Super Cruise Buttons (if selected) Bar Symbol Symbol Camera 2 SUPER CRUISE OPERATION Super Cruise is a hands-free driver assistance feature for use on While Super Cruise is engaged, an escalating series of prompts lets compatible highways. The system steers the vehicle to maintain you know if the Driver Attention Camera senses that you need to pay lane position while also monitoring your attention to the road. more attention to the road ahead. Working with the Adaptive Cruise Control–Advanced system, it The steering wheel light bar intuitively provides a status of system reduces the need for you to frequently steer, brake or accelerate operation, including when the system is steering and when you under available operating conditions. need to manually steer the vehicle. You can override Super Cruise at To maintain automatic control of vehicle steering during high- any time by steering, braking or accelerating. way driving, Super Cruise uses Global Positioning System (GPS) If you do not respond to system prompts to manually steer the sensing, GPS-enhanced data, a high precision map, and a network vehicle, Super Cruise will be disabled and OnStar will be contacted of cameras. -

Combined Brake and Steering Actuator for Automatic Vehicle Control

CALIFORNIA PATH PROGRAM INSTITUTE OF TRANSPORTATION STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Combined Brake and Steering Actuator for Automatic Vehicle Control R. Prohaska, P. Devlin California PATH Working Paper UCB-ITS-PWP-98-15 This work was performed as part of the California PATH Program of the University of California, in cooperation with the State of California Business, Transportation, and Housing Agency, Department of Trans- portation; and the United States Department Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the State of California. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. Report for MOU 331 August 1998 ISSN 1055-1417 CALIFORNIA PARTNERS FOR ADVANCED TRANSIT AND HIGHWAYS Combined Brake and Steering Actuator for Automatic Vehicle Research y R. Prohaska and P. Devlin University of California PATH, 1357 S. 46th St. Richmond CA 94804 Decemb er 8, 1997 Abstract A simple, relatively inexp ensive combined steering and brake actuator system has b een develop ed for use in automatic vehicle control research. It allows a standard passenger car to switch from normal manual op eration to automatic op eration and back seamlessly using largely standard parts. The only critical comp onents required are twovalve sp o ols which can b e made on a small precision lathe. All other parts are either o the shelf or can b e fabricated using standard shop to ols. The system provides approximately 3 Hz small signal steering bandwidth combined with 90 ms large signal brake pressure risetime. -

Terrain-Adaptive Cruise-Control: a Human-Like Approach

TERRAIN-ADAPTIVE CRUISE-CONTROL: A HUMAN-LIKE APPROACH A Dissertation by NARAYANI VEDAM Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Chair of Committee, Shankar P. Bhattacharyya Co-Chair of Committee, Reza Langari Committee Members, Aniruddha Datta Ben Zoghi Head of Department, Miroslav M. Begovic December 2015 Major Subject: Electrical Engineering Copyright 2015 Narayani Vedam ABSTRACT With rapid advancements in the field of autonomous vehicles, intelligent control systems and automated highway systems, the need for GPS based vehicle data has grown in importance. This has provided for a plethora of opportunities to improve upon the existing vehicular systems. In this study, the use of GPS data for optimal regulation of vehicle speed is ex- plored. A discrete dynamic programming algorithm with a model predictive control (MPC) scheme is employed. The objective function is formulated in such a way that the weighting gains vary adaptively based on the road slope. Unlike in the prevalent approaches, this eliminates the need for a preprocessing algorithm to ensure tracking along flat stretches of road. Fuel savings of 0.48% along a downhill have been recorded. Also, the usage of brakes has been considerably reduced due to deceleration prior to descent. This is highly advantageous, particularly in the case of heavy-duty vehicles as they are prone to wearing of brake pad lining. Therefore, this method proves to be a simpler alternative to the existing methods, while incorporating the best attributes of a human driver and the tracking ability of a conventional controller.