Governance and Militancy in Pakistan's Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Single Stage Two Envelope E-Bidding System)

GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA C&W DEPARTMENT HIGHWAY DIVISION MARDAN. NOTICE INVITING E-BDDING (Single Stage two envelope E-Bidding System) Communication & works Department Highway Division Mardan invites electronic Bids from eligible firms /contractors in accordance with KPPRA procurement Rules 2014 on single stage two envelope E-Bidding procedure for the works as given in below table. The Bidders should be registered with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Revenue Authority (KPRA) and Pakistan Engineering Council (PEC) in relevant category & field of specialization. The firms already enlisted with C&W Department having adequate financial soundness, relevant experience, personnel capabilities, required equipments and others requirement as included in ITB can participate in the tenders: Date of Required Estimated Bid Period of Last date opening and S# Name of Work category of Cost Security completio and time of (Rs. in (Rs. in time PEC/ PKHA n submission Millions) Millions) Technical bid ADP No. 1706/200252 CONSTRUCTION OF TECHNICALLY & ECONOMICALLY FEASIBLE 100 KMS ROADS IN MARDAN DIVISION 1 On same day at PK-C3 & 32 22/01/2021 Dulization of Mardan Toru Road 255.144 5102880 1230 Hours above months at 1200 Hours 2 i. Construction / Black Topping of Baba Koroona Masjid to Neher Road. ii. Construction / Black Topping of Ghari Doulat zai to Baghicha Dheri Uc Ghari iii. Construction / Black Topping of Roghano Banda Road Uc Bakhshali. iv. Construction / Black Topping of Main Rustam Teacher Killi to chanraka Road Uc Shahbaz Ghari. On same day at PK-C4 & 32 22/01/2021 150.000 3000000/- 1230 Hours v. Rehabilitation And Improvement of at 1200 Hours above months PCC Road of Nisatta Road Aslam Abad New Coloney Mirwas Uc Rural Mardan vi. -

A Case Study of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Mishaal Afteb University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Honors Scholar Theses Honors Scholar Program Spring 5-2-2019 Decentralization and the Provision of Public Services: A Case Study of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Mishaal Afteb University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Other International and Area Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Afteb, Mishaal, "Decentralization and the Provision of Public Services: A Case Study of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan" (2019). Honors Scholar Theses. 608. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/608 Decentralization and the Provision of Public Services: A Case Study of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Abstract: The effective provision of public services is integral to a functioning democracy as it connects the public to the government and grants it legitimacy. Public services are ones that are provided by the federal and local governments and paid for with constituent taxes. Public services provided by the state are education, health, water/sanitation, environmental measures, security, policing, labor and legal guidelines and so on. Whether the structure of the government is centralized or decentralized is an important factor which impacts the provision of services. Decentralized governments are state or local governments which receive monetary and institutional resources from the federal government. Previous research has shown that decentralized services are more effectively delivered than centralized services. My study examines the impact of decentralization on the provision of two services, health and education, in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa from 2008-2018. There are two parts to the study. First, I will use process tracing to portray the historical context of decentralization in conjunction with sociopolitical factors of the region of KP. -

Pdf | 951.36 Kb

P a g e | 1 Operation Updates Report Pakistan: Monsoon Floods DREF n° MDRPK019 GLIDE n° FL-2020-000185-PAK Operation update n° 1; Date of issue: 6/10/2020 Timeframe covered by this update: 10/08/2020 – 07/09/2020 Operation start date: 10/08/2020 Operation timeframe: 6 months; End date: 28/02/2021 Funding requirements (CHF): DREF second allocation amount CHF 339,183 (Initial DREF CHF 259,466 - Total DREF budget CHF 598,649) N° of people being assisted: 96,250 (revised from the initially planned 68,250 people) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: IFRC Pakistan Country Office is actively involved in the coordination and is supporting Pakistan Red Crescent Society (PRCS) in this operation. In addition, PRCS is maintaining close liaison with other in-country Movement partners: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), German Red Cross (GRC), Norwegian Red Cross (NorCross) and Turkish Red Crescent Society (TRCS) – who are likely to support the National Society’s response. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), Provincial Disaster Management Authorities (PDMAs), District Administration, United Nations (UN) and local NGOs. Summary of major revisions made to emergency plan of action: Another round of continuous heavy rains started in most part of the country on the week of 20 August 2020 until 3 September 2020 intermittently. The second round of torrential rains caused urban flooding in the Sindh province and flash flooding in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). New areas have been affected by the urban flooding including the districts of Malir, Karachi Central, Karachi West, Karachi East and Korangi (Sindh), and District Shangla, Swat and Charsadda in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. -

Sindh Coast: a Marvel of Nature

Disclaimer: This ‘Sindh Coast: A marvel of nature – An Ecotourism Guidebook’ was made possible with support from the American people delivered through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of IUCN Pakistan and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of USAID or the U.S. Government. Published by IUCN Pakistan Copyright © 2017 International Union for Conservation of Nature. Citation is encouraged. Reproduction and/or translation of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from IUCN Pakistan, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from IUCN Pakistan. Author Nadir Ali Shah Co-Author and Technical Review Naveed Ali Soomro Review and Editing Ruxshin Dinshaw, IUCN Pakistan Danish Rashdi, IUCN Pakistan Photographs IUCN, Zahoor Salmi Naveed Ali Soomro, IUCN Pakistan Designe Azhar Saeed, IUCN Pakistan Printed VM Printer (Pvt.) Ltd. Table of Contents Chapter-1: Overview of Ecotourism and Chapter-4: Ecotourism at Cape Monze ....... 18 Sindh Coast .................................................... 02 4.1 Overview of Cape Monze ........................ 18 1.1 Understanding ecotourism...................... 02 4.2 Accessibility and key ecotourism 1.2 Key principles of ecotourism................... 03 destinations ............................................. 18 1.3 Main concepts in ecotourism ................. -

Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa

Working paper Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth Full Report April 2015 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: F-37109-PAK-1 Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth International Growth Centre, Pakistan Program The International Growth Centre (IGC) aims to promote sustainable growth in developing countries by providing demand-led policy advice informed by frontier research. Based at the London School of Economics and in partnership with Oxford University, the IGC is initiated and funded by DFID. The IGC has 15 country programs. This report has been prepared under the overall supervision of the management team of the IGC Pakistan program: Ijaz Nabi (Country Director), Naved Hamid (Resident Director) and Ali Cheema (Lead Academic). The coordinators for the report were Yasir Khan (IGC Country Economist) and Bilal Siddiqi (Stanford). Shaheen Malik estimated the provincial accounts, Sarah Khan (Columbia) edited the report and Khalid Ikram peer reviewed it. The authors include Anjum Nasim (IDEAS, Revenue Mobilization), Osama Siddique (LUMS, Rule of Law), Turab Hussain and Usman Khan (LUMS, Transport, Industry, Construction and Regional Trade), Sarah Saeed (PSDF, Skills Development), Munir Ahmed (Energy and Mining), Arif Nadeem (PAC, Agriculture and Livestock), Ahsan Rana (LUMS, Agriculture and Livestock), Yasir Khan and Hina Shaikh (IGC, Education and Health), Rashid Amjad (Lahore School of Economics, Remittances), GM Arif (PIDE, Remittances), Najm-ul-Sahr Ata-ullah and Ibrahim Murtaza (R. Ali Development Consultants, Urbanization). For further information please contact [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] . -

A Comparative Study of Directly Selected, In-Service Promoted and Online Selected Subject Specialists Regarding Teaching Effectiveness in Kohat Division, Pakistan

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.6, No.10, 2015 A Comparative Study of Directly Selected, In-Service Promoted and Online Selected Subject Specialists Regarding Teaching Effectiveness in Kohat Division, Pakistan Qaiser Suleman PhD (Education) Scholar, Institute of Education & Research, Kohat University of Science & Technology Kohat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, (Pakistan) Email: [email protected] Rizwana Gul M.Phil (Education) Scholar, Institute of Education & Research, Kohat University of Science & Technology Kohat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, (Pakistan) Abstract The main objective of the study was to compare the teaching effectiveness of directly selected, in-service promoted and online selected subject specialists teaching at higher secondary school level in Kohat Division, Pakistan. The target population of the study was the higher secondary school students in Kohat Division, Pakistan. A sample of 600 students randomly selected from 10 out of 20 higher secondary schools in Kohat Division was used in this study. The design of this research study was survey. A self-developed structured questionnaire was used a research instrument for data collection. Statistical tools i.e., mean, standard deviation, ANOVA and Post-hoc t-tests were used. After statistical analysis, it was concluded that the teaching performance of the directly selected subject specialists was highly appreciable and excellent. On the other hand, teaching performance of in-service promoted subject specialists was found satisfactory while teaching performance of online selected subject specialists was poor and unsatisfactory. Based on findings, it was recommended that at least 75% of the total subject specialists should be recruited through Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Public Service Commission only. -

Assessing the 2017 Census of Pakistan Using Demographic Analysis: a Sub-National Perspective

WWW.OEAW.AC.AT VIENNA INSTITUTE OF DEMOGRAPHY WORKING PAPERS 06/2019 ASSESSING THE 2017 CENSUS OF PAKISTAN USING DEMOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS: A SUB-NATIONAL PERSPECTIVE MUHAMMAD ASIF WAZIR AND ANNE GOUJON Vienna Institute of Demography Austrian Academy of Sciences Welthandelsplatz 2, Level 2 | 1020 Wien, Österreich [email protected] | www.oeaw.ac.at/vid DEMOGRAPHY OF INSTITUTE VIENNA – VID Abstract In 2017, Pakistan implemented a long-awaited population census since the last one conducted in 1998. However, several experts are contesting the validity of the census data at the sub-national level, in the absence of a post-enumeration survey. We propose in this paper to use demographic analysis to assess the quality of the 2017 census at the sub- national level, using the 1998 census data and all available intercensal surveys. Applying the cohort-component method of population projection, we subject each six first-level subnational entities for which data are available to estimates regarding the level of fertility, mortality, international, and internal migration. We arrive at similar results as the census at the national level: an estimated 212.4 million compared to 207.7 million counted (2.3% difference). However, we found more variations at the sub-national level. Keywords Census, population projections, reconstruction, Pakistan, Pakistan provinces. Authors Muhammad Asif Wazir (corresponding author), United Nations Population Fund, Islamabad, Pakistan. Email: [email protected] Anne Goujon, Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, VID/ÖAW, WU), Vienna Institute of Demography, Austrian Academy of Sciences and World Population Program, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. Email: [email protected] Acknowledgments This study is based on the publically available data and was not funded. -

Gathered Wild Food Plants Among Diverse Religious Groups in Jhelum District, Punjab, Pakistan

foods Article Gathered Wild Food Plants among Diverse Religious Groups in Jhelum District, Punjab, Pakistan Muhammad Majeed 1, Khizar Hayat Bhatti 1, Andrea Pieroni 2,3 , Renata Sõukand 4 , Rainer W. Bussmann 5 , Arshad Mahmood Khan 6 , Sunbal Khalil Chaudhari 7, Muhammad Abdul Aziz 2 and Muhammad Shoaib Amjad 8,* 1 Department of Botany, Hafiz Hayat Campus, University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Punjab 50700, Pakistan; [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (K.H.B.) 2 University of Gastronomic Sciences, Piazza Vittorio Emanuele II 9, 12042 Pollenzo/Bra (Cuneo), Italy; [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (M.A.A.) 3 Department of Medical Analysis, Tishk International University, Erbil 4401, Iraq 4 Department of Environmental Sciences, Informatics and Statistics, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Via Torino 155, 30172 Mestre, Italy; [email protected] 5 Department of Ethnobotany, Institute of Botany, Ilia State University, Tbilisi 0162, Georgia; [email protected] 6 Department of Botany, Govt. Hashmat Ali Islamia Degree College Rawalpindi, Rawalpindi 46000, Pakistan; [email protected] 7 Department of Botany, Sargodha Campus, Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, The University of Lahore, Sargodha 40100, Pakistan; [email protected] 8 Department of Botany, Women University of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Bagh 12500, Pakistan * Correspondence: [email protected] Citation: Majeed, M.; Bhatti, K.H.; Abstract: Recent ethnobotanical studies have raised the hypothesis that religious affiliation can, in Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R.; Bussmann, certain circumstances, influence the evolution of the use of wild food plants, given that it shapes R.W.; Khan, A.M.; Chaudhari, S.K.; kinship relations and vertical transmission of traditional/local environmental knowledge. -

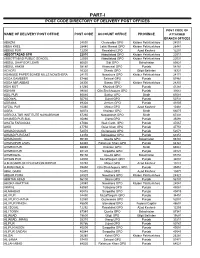

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

Province Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province Punjab

PAKISTAN BAIT-UL-MAL Vocational Dastkari School/Diversified Vocational Dastkari School Province Khyber Pakhtunkhwa S# District VDS / DVDS ADDRESSES 1 Khyber Agency Achani Ring Road Peshawar Tel:0333-9124637 2 Peshawar Diamond Street, T.V Colony, Ali Khan Town, Swati Patak Tel:0315-9151368 3 Nowshehra Adda Bazar, Moh, Anwar Abad, Near Tariq Bakers Akora Khattak 4 Charsadda (City) Moh. Paida Khel, Old Bazar Charsadda 5 Charsadda (Tangi) Almadina Colony 6 Mardan (City) Muslim Abad, New Lakhte Korona, Near Bismillah Mosque, Dagai Tel:0314-9391148 7 Mardan (Takhtbai) Moh. Sher Qayum, Sharif Abad Takhtbai Tel:0315-9372724 8 Swabi Mal Shagai,, Near Degree College for Women, Mardan Road 9 Haripur (City) Mankara Road, Mohallah, Saeed Abad. Haripur Tel:0333-9395035 10 Haripur (Central Jail) Central Jail Haripur Tel:0315-3142220 11 Kohat BangashAbad, Kohat City 12 Karak Near Session Court Tel:0927-210436 13 Hangu Muslim Abad Hangu Tel:0332-9672487 14 Abbottabad Orash Colony, Nawan Sheher, Abbotabad Tel:0321-5820210 15 Mansehra Mohalla Dhab Safdar Road Tel:0345-6097014 16 Battagram Village, Ajmira Tel:Not Awailable 17 Tank Moh:Poolshah Gulabi Pump 18 DI Khan Mohall Jogiawala Tel:0346-3843532 19 Bannu Kot Barara Tel: Not available 20 Dir (Upper) Main Bazar, 21 Lakki Marwat Near ZTBL, Lakki City 22 Buner Par baba, bacha kali Buner Tel:0345-3728744 23 Swat Bar Kalai, Saidu Sharif 24 Shangla par Alpuri, Head Quarter Shangla 25 Chitral Village Broze, Chitral Tel:0342-9868388 26 Dir (Lower) Near DHQ Hospital Balambat Tel:0344-9236037 27 Malakand Moh: Sharifabad Batkhela 28 Momand Agency Mian Mandai, Haleem Zai Tel:0344-9846677 29 Kurram Agency Main Kachehri Parachinar Tel:926312734 30 Bajur Agency Near Sabzi Mandin Khar Province Punjab Sr. -

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Daily Situation Report Infra/ Human Incidents Incidents Detail Roads Blockage

PDMA PROVINCIAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY Provincial Emergency Operation Center Plot 46 A, Sector B2, Phase V, Hayatabad,Peshawar Phone: (091) 9219635, 9219636, Fax: (091) 9219637 www.pdma.gov.pk No. PDMA/PEOC/DSR/2021/AugM225 Date: 02/08/2021 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA DAILY SITUATION REPORT INFRA/ HUMAN INCIDENTS NATURE OF CAUSE OF CATTLE DISTRICT HUMAN LOSSES/ INJURIES INFRASTRUCTURE DAMAGES INCIDENT INCIDENT PERISHED DEATH INJURED HOUSES SCHOOLS OTHERS Mae Female Child Total Male Female Child Total Fully Partially Total Fully Partially Total Fully Partially Total Mardan Electrocution Electric Shock 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Abbottabad Heavy Rain Cattle Shed 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 17 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 Boundry Wall Dera Ismail Heavy Rain Collapse/Room 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 Khan Collapse Total(s) 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 17 0 3 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 INCIDENTS DETAIL DISTRICT DETAIL OF INCIDENT RESPONSE SOURCE On 02082021, due to heavy rain a cattle shed in a house of Mr. Abbottabad Muhammad Yousaf s/o Khaniz Khan r/o Halqa Jamhar Mauza Baghdara Reporting Officer Hazara Division got collapsed. Resultantly 17 goats got perished. On 01082021, due to heavy rain 2 rooms of a house of Mr. Imam Bakhsh s/o Sarband Qoaum Doop r/o Ghar Rasheed DIKhan collapsed. Reporting Officer DI Khan Division However, no human loss reported. -

Table 13.1 Pakistan Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province

PAKISTAN TABLE 13.1 NUMBER AND AREA OF OWNERS BY SIZE OF AREA OWNED (AREA IN HECTARES) OWNERS AREA OWNED SIZE OF AREA OWNED (HECTARES) NUMBER PERCENT TOTAL PERCENT 1 2 3 4 5 PAKISTAN PRIVATE OWNERSHIP-TOTAL ... 8355757 100 22500282 100 UNDER 0.5 ... 2326644 28 606718 3 0.5 TO UNDER 1.0 ... 1573313 19 1173145 5 1.0 TO UNDER 2.0 ... 1698718 20 2339193 10 2.0 TO UNDER 3.0 ... 1075357 13 2485558 11 3.0 TO UNDER 5.0 ... 840370 10 3243244 14 5.0 TO UNDER 10.0 ... 512011 6 3463205 15 10.0 TO UNDER 20.0 ... 215519 3 2769199 12 20.0 TO UNDER 40.0 ... 76835 1 1929621 9 40.0 TO UNDER 60.0 ... 17699 * 793345 4 60.0 AND ABOVE........... 19291 * 3697054 16 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PROVINCE PRIVATE OWNERSHIP-TOTAL ... 1599908 100 2399681 100 UNDER 0.5 ... 716777 45 167395 7 0.5 TO UNDER 1.0 ... 322640 20 232097 10 1.0 TO UNDER 2.0 ... 264272 17 358892 15 2.0 TO UNDER 3.0 ... 126310 8 291418 12 3.0 TO UNDER 5.0 ... 91202 6 345983 14 5.0 TO UNDER 10.0 ... 48314 3 325733 14 10.0 TO UNDER 20.0 ... 20266 1 256654 11 20.0 TO UNDER 40.0 ... 7203 * 179046 7 40.0 TO UNDER 60.0 ... 1666 * 73559 3 60.0 AND ABOVE........... 1258 * 168904 7 PUNJAB PROVINCE PRIVATE OWNERSHIP-TOTAL ... 5459120 100 11646897 100 UNDER 0.5 ... 1431215 26 377875 3 0.5 TO UNDER 1.0 ... 1059101 19 790259 7 1.0 TO UNDER 2.0 ..