Lineage-Defined Leiomyosarcoma Subtypes Emerge Years Before Diagnosis and Determine Patient Survival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Increased Expression of the Tail-Anchored Membrane Protein SLMAP in Adipose Tissue from Type 2 Tally Ho Diabetic Mice

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Experimental Diabetes Research Volume 2011, Article ID 421982, 10 pages doi:10.1155/2011/421982 Research Article Increased Expression of the Tail-Anchored Membrane Protein SLMAP in Adipose Tissue from Type 2 Tally Ho Diabetic Mice Xiaoliang Chen1 and Hong Ding2 1 Second People Hospital of Hangzhou, No. 1 Wenzhou Road, Hangzhou 310015, China 2 Department of Pharmacology, Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar, P.O. Box 24144, Doha, Qatar Correspondence should be addressed to Hong Ding, [email protected] Received 6 April 2011; Accepted 5 May 2011 Academic Editor: N. Cameron Copyright © 2011 X. Chen and H. Ding. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The tail-anchored membrane protein, sarcolemmal membrane associated protein (SLMAP) is encoded to a single gene that maps to the chromosome 3p14 region and has also been reported in certain diabetic populations. Our previous studies with db/db mice shown that a deregulation of SLMAP expression plays an important role in type 2 diabetes. Male Tally Ho mice were bred to present with either normoglycemia (NG) or hyperglycemia (HG). Abdominal adipose tissue from male Tally Ho mice of the HG group was found to have a significantly lower expression of the membrane associated glucose transporter-4 (GLUT-4) and higher expression of SLMAP compared to tissue from NG mice. There were 3 isoforms expressed in the abdominal adipose tissue, but only 45 kDa isoform of SLMAP was associated with the GLUT-4 revealed by immunoprecipitation data. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Investigation of the Underlying Hub Genes and Molexular Pathogensis in Gastric Cancer by Integrated Bioinformatic Analyses

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.20.423656; this version posted December 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Investigation of the underlying hub genes and molexular pathogensis in gastric cancer by integrated bioinformatic analyses Basavaraj Vastrad1, Chanabasayya Vastrad*2 1. Department of Biochemistry, Basaveshwar College of Pharmacy, Gadag, Karnataka 582103, India. 2. Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001, Karanataka, India. * Chanabasayya Vastrad [email protected] Ph: +919480073398 Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001 , Karanataka, India bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.20.423656; this version posted December 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract The high mortality rate of gastric cancer (GC) is in part due to the absence of initial disclosure of its biomarkers. The recognition of important genes associated in GC is therefore recommended to advance clinical prognosis, diagnosis and and treatment outcomes. The current investigation used the microarray dataset GSE113255 RNA seq data from the Gene Expression Omnibus database to diagnose differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Pathway and gene ontology enrichment analyses were performed, and a proteinprotein interaction network, modules, target genes - miRNA regulatory network and target genes - TF regulatory network were constructed and analyzed. Finally, validation of hub genes was performed. The 1008 DEGs identified consisted of 505 up regulated genes and 503 down regulated genes. -

PRODUCT SPECIFICATION Anti-C22orf23 Product Datasheet

Anti-C22orf23 Product Datasheet Polyclonal Antibody PRODUCT SPECIFICATION Product Name Anti-C22orf23 Product Number HPA000650 Gene Description chromosome 22 open reading frame 23 Clonality Polyclonal Isotype IgG Host Rabbit Antigen Sequence Recombinant Protein Epitope Signature Tag (PrEST) antigen sequence: LQCSPTSSQRVLPSKQIASPIYLPPILAARPHLRPANMCQANGAYSREQF KPQATRDLEKEKQRLQNIFATGKDMEERKRKAPPARQKAPAPELDRFEEL VKEIQERKEFLADMEALGQGKQYRGIILAEISQKLREMEDIDHRRSEE Purification Method Affinity purified using the PrEST antigen as affinity ligand Verified Species Human Reactivity Recommended ICC-IF (Immunofluorescence) Applications - Fixation/Permeabilization: PFA/Triton X-100 - Working concentration: 0.25-2 µg/ml Characterization Data Available at atlasantibodies.com/products/HPA000650 Buffer 40% glycerol and PBS (pH 7.2). 0.02% sodium azide is added as preservative. Concentration Lot dependent Storage Store at +4°C for short term storage. Long time storage is recommended at -20°C. Notes Gently mix before use. Optimal concentrations and conditions for each application should be determined by the user. For protocols, additional product information, such as images and references, see atlasantibodies.com. Product of Sweden. For research use only. Not intended for pharmaceutical development, diagnostic, therapeutic or any in vivo use. No products from Atlas Antibodies may be resold, modified for resale or used to manufacture commercial products without prior written approval from Atlas Antibodies AB. Warranty: The products supplied by Atlas Antibodies are warranted to meet stated product specifications and to conform to label descriptions when used and stored properly. Unless otherwise stated, this warranty is limited to one year from date of sales for products used, handled and stored according to Atlas Antibodies AB's instructions. Atlas Antibodies AB's sole liability is limited to replacement of the product or refund of the purchase price. -

Metastatic Adrenocortical Carcinoma Displays Higher Mutation Rate and Tumor Heterogeneity Than Primary Tumors

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-06366-z OPEN Metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma displays higher mutation rate and tumor heterogeneity than primary tumors Sudheer Kumar Gara1, Justin Lack2, Lisa Zhang1, Emerson Harris1, Margaret Cam2 & Electron Kebebew1,3 Adrenocortical cancer (ACC) is a rare cancer with poor prognosis and high mortality due to metastatic disease. All reported genetic alterations have been in primary ACC, and it is 1234567890():,; unknown if there is molecular heterogeneity in ACC. Here, we report the genetic changes associated with metastatic ACC compared to primary ACCs and tumor heterogeneity. We performed whole-exome sequencing of 33 metastatic tumors. The overall mutation rate (per megabase) in metastatic tumors was 2.8-fold higher than primary ACC tumor samples. We found tumor heterogeneity among different metastatic sites in ACC and discovered recurrent mutations in several novel genes. We observed 37–57% overlap in genes that are mutated among different metastatic sites within the same patient. We also identified new therapeutic targets in recurrent and metastatic ACC not previously described in primary ACCs. 1 Endocrine Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA. 2 Center for Cancer Research, Collaborative Bioinformatics Resource, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA. 3 Department of Surgery and Stanford Cancer Institute, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to E.K. (email: [email protected]) NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | (2018) 9:4172 | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-06366-z | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 ARTICLE NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-06366-z drenocortical carcinoma (ACC) is a rare malignancy with types including primary ACC from the TCGA to understand our A0.7–2 cases per million per year1,2. -

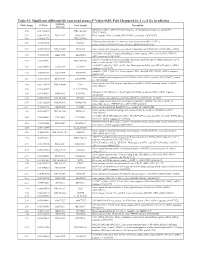

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds. -

NRF1) Coordinates Changes in the Transcriptional and Chromatin Landscape Affecting Development and Progression of Invasive Breast Cancer

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-7-2018 Decipher Mechanisms by which Nuclear Respiratory Factor One (NRF1) Coordinates Changes in the Transcriptional and Chromatin Landscape Affecting Development and Progression of Invasive Breast Cancer Jairo Ramos [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Clinical Epidemiology Commons Recommended Citation Ramos, Jairo, "Decipher Mechanisms by which Nuclear Respiratory Factor One (NRF1) Coordinates Changes in the Transcriptional and Chromatin Landscape Affecting Development and Progression of Invasive Breast Cancer" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3872. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3872 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida DECIPHER MECHANISMS BY WHICH NUCLEAR RESPIRATORY FACTOR ONE (NRF1) COORDINATES CHANGES IN THE TRANSCRIPTIONAL AND CHROMATIN LANDSCAPE AFFECTING DEVELOPMENT AND PROGRESSION OF INVASIVE BREAST CANCER A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in PUBLIC HEALTH by Jairo Ramos 2018 To: Dean Tomás R. Guilarte Robert Stempel College of Public Health and Social Work This dissertation, Written by Jairo Ramos, and entitled Decipher Mechanisms by Which Nuclear Respiratory Factor One (NRF1) Coordinates Changes in the Transcriptional and Chromatin Landscape Affecting Development and Progression of Invasive Breast Cancer, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

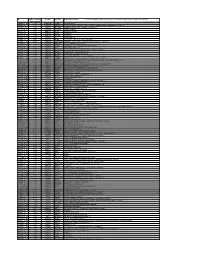

ID AKI Vs Control Fold Change P Value Symbol Entrez Gene Name *In

ID AKI vs control P value Symbol Entrez Gene Name *In case of multiple probesets per gene, one with the highest fold change was selected. Fold Change 208083_s_at 7.88 0.000932 ITGB6 integrin, beta 6 202376_at 6.12 0.000518 SERPINA3 serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A (alpha-1 antiproteinase, antitrypsin), member 3 1553575_at 5.62 0.0033 MT-ND6 NADH dehydrogenase, subunit 6 (complex I) 212768_s_at 5.50 0.000896 OLFM4 olfactomedin 4 206157_at 5.26 0.00177 PTX3 pentraxin 3, long 212531_at 4.26 0.00405 LCN2 lipocalin 2 215646_s_at 4.13 0.00408 VCAN versican 202018_s_at 4.12 0.0318 LTF lactotransferrin 203021_at 4.05 0.0129 SLPI secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor 222486_s_at 4.03 0.000329 ADAMTS1 ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 1 1552439_s_at 3.82 0.000714 MEGF11 multiple EGF-like-domains 11 210602_s_at 3.74 0.000408 CDH6 cadherin 6, type 2, K-cadherin (fetal kidney) 229947_at 3.62 0.00843 PI15 peptidase inhibitor 15 204006_s_at 3.39 0.00241 FCGR3A Fc fragment of IgG, low affinity IIIa, receptor (CD16a) 202238_s_at 3.29 0.00492 NNMT nicotinamide N-methyltransferase 202917_s_at 3.20 0.00369 S100A8 S100 calcium binding protein A8 215223_s_at 3.17 0.000516 SOD2 superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial 204627_s_at 3.04 0.00619 ITGB3 integrin, beta 3 (platelet glycoprotein IIIa, antigen CD61) 223217_s_at 2.99 0.00397 NFKBIZ nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, zeta 231067_s_at 2.97 0.00681 AKAP12 A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 12 224917_at 2.94 0.00256 VMP1/ mir-21likely ortholog -

Role of SLMAP Genetic Variants in Susceptibility Of

Upadhyay et al. Journal of Translational Medicine (2015) 13:61 DOI 10.1186/s12967-015-0411-6 RESEARCH Open Access Role of SLMAP genetic variants in susceptibility of diabetes and diabetic retinopathy in Qatari population Rohit Upadhyay1, Amal Robay2, Khalid Fakhro2, Charbel Abi Khadil2, Mahmoud Zirie3, Amin Jayyousi3, Maha El-Shafei4, Szilard Kiss5, Donald J D′Amico5, Jacqueline Salit6, Michelle R Staudt6, Sarah L O′Beirne6, Xiaoliang Chen7, Balwant Tuana8, Ronald G Crystal6 and Hong Ding1* Abstract Background: Overexpression of SLMAP gene has been associated with diabetes and endothelial dysfunction of macro- and micro-blood vessels. In this study our primary objective is to explore the role of SLMAP gene polymorphisms in the susceptibility of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) with or without diabetic retinopathy (DR) in the Qatari population. Methods: A total of 342 Qatari subjects (non-diabetic controls and T2DM patients with or without DR) were genotyped for SLMAP gene polymorphisms (rs17058639 C > T; rs1043045 C > T and rs1057719 A > G) using Taqman SNP genotyping assay. Results: SLMAP rs17058639 C > T polymorphism was associated with the presence of DR among Qataris with T2DM. One-way ANOVA and multiple logistic regression analysis showed SLMAP SNP rs17058639 C > T as an independent risk factor for DR development. SLMAP rs17058639 C > T polymorphism also had a predictive role for the severity of DR. Haplotype Crs17058639Trs1043045Ars1057719 was associated with the increased risk for DR among Qataris with T2DM. Conclusions: The data suggests the potential role of SLMAP SNPs as a risk factor for the susceptibility of DR among T2DM patients in the Qatari population. -

Co-Evolution of B7H6 and Nkp30, Identification of a New B7 Family Member, B7H7, and of B7's Historical Relationship with the MHC

Immunogenetics (2012) 64:571–590 DOI 10.1007/s00251-012-0616-2 ORIGINAL PAPER Evolution of the B7 family: co-evolution of B7H6 and NKp30, identification of a new B7 family member, B7H7, and of B7's historical relationship with the MHC Martin F. Flajnik & Tereza Tlapakova & Michael F. Criscitiello & Vladimir Krylov & Yuko Ohta Received: 19 January 2012 /Accepted: 20 March 2012 /Published online: 11 April 2012 # Springer-Verlag 2012 Abstract The B7 family of genes is essential in the regula- Furthermore, we identified a Xenopus-specific B7 homolog tion of the adaptive immune system. Most B7 family mem- (B7HXen) and revealed its close linkage to B2M, which we bers contain both variable (V)- and constant (C)-type have demonstrated previously to have been originally domains of the immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF). encoded in the MHC. Thus, our study provides further proof Through in silico screening of the Xenopus genome and that the B7 precursor was included in the proto MHC. subsequent phylogenetic analysis, we found novel genes Additionally, the comparative analysis revealed a new B7 belonging to the B7 family, one of which is the recently family member, B7H7, which was previously designated in discovered B7H6. Humans and rats have a single B7H6 the literature as an unknown gene, HHLA2. gene; however, many B7H6 genes were detected in a single large cluster in the Xenopus genome. The B7H6 expression Keywords B7 family. MHC . Evolution . Natural killer patterns also varied in a species-specific manner. Human receptors . Genetic linkage . Xenopus B7H6 binds to the activating natural killer receptor, NKp30. While the NKp30 gene is single-copy and maps to the MHC in most vertebrates, many Xenopus NKp30 genes were Introduction found in a cluster on a separate chromosome that does not harbor the MHC. -

PDF Datasheet

Product Datasheet EVG1 Overexpression Lysate NBP2-05986 Unit Size: 0.1 mg Store at -80C. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles. Protocols, Publications, Related Products, Reviews, Research Tools and Images at: www.novusbio.com/NBP2-05986 Updated 3/17/2020 v.20.1 Earn rewards for product reviews and publications. Submit a publication at www.novusbio.com/publications Submit a review at www.novusbio.com/reviews/destination/NBP2-05986 Page 1 of 2 v.20.1 Updated 3/17/2020 NBP2-05986 EVG1 Overexpression Lysate Product Information Unit Size 0.1 mg Concentration The exact concentration of the protein of interest cannot be determined for overexpression lysates. Please contact technical support for more information. Storage Store at -80C. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles. Buffer RIPA buffer Target Molecular Weight 24.8 kDa Product Description Description Transient overexpression lysate of chromosome 22 open reading frame 23 (C22orf23) The lysate was created in HEK293T cells, using Plasmid ID RC204555 and based on accession number NM_032561. The protein contains a C-MYC/DDK Tag. Gene ID 84645 Gene Symbol C22ORF23 Species Human Notes HEK293T cells in 10-cm dishes were transiently transfected with a non-lipid polymer transfection reagent specially designed and manufactured for large volume DNA transfection. Transfected cells were cultured for 48hrs before collection. The cells were lysed in modified RIPA buffer (25mM Tris-HCl pH7.6, 150mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1mM EDTA, 1xProteinase inhibitor cocktail mix, 1mM PMSF and 1mM Na3VO4, and then centrifuged to clarify the lysate. Protein concentration was measured by BCA protein assay kit.This product is manufactured by and sold under license from OriGene Technologies and its use is limited solely for research purposes. -

Comprehensive Analysis Reveals Novel Gene Signature in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Predicting Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Patients

5892 Original Article Comprehensive analysis reveals novel gene signature in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: predicting is associated with poor prognosis in patients Yixin Sun1,2#, Quan Zhang1,2#, Lanlin Yao2#, Shuai Wang3, Zhiming Zhang1,2 1Department of Breast Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China; 2School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China; 3State Key Laboratory of Cellular Stress Biology, School of Life Sciences, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China Contributions: (I) Conception and design: Y Sun, Q Zhang; (II) Administrative support: Z Zhang; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: Y Sun, Q Zhang; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: Y Sun, L Yao; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: Y Sun, S Wang; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. #These authors contributed equally to this work. Correspondence to: Zhiming Zhang. Department of Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, Xiamen, China. Email: [email protected]. Background: Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC) remains an important public health problem, with classic risk factors being smoking and excessive alcohol consumption and usually has a poor prognosis. Therefore, it is important to explore the underlying mechanisms of tumorigenesis and screen the genes and pathways identified from such studies and their role in pathogenesis. The purpose of this study was to identify genes or signal pathways associated with the development of HNSC. Methods: In this study, we downloaded gene expression profiles of GSE53819 from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, including 18 HNSC tissues and 18 normal tissues.