{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Immersion Into Noise

Immersion Into Noise Critical Climate Change Series Editors: Tom Cohen and Claire Colebrook The era of climate change involves the mutation of systems beyond 20th century anthropomorphic models and has stood, until recent- ly, outside representation or address. Understood in a broad and critical sense, climate change concerns material agencies that im- pact on biomass and energy, erased borders and microbial inven- tion, geological and nanographic time, and extinction events. The possibility of extinction has always been a latent figure in textual production and archives; but the current sense of depletion, decay, mutation and exhaustion calls for new modes of address, new styles of publishing and authoring, and new formats and speeds of distri- bution. As the pressures and re-alignments of this re-arrangement occur, so must the critical languages and conceptual templates, po- litical premises and definitions of ‘life.’ There is a particular need to publish in timely fashion experimental monographs that redefine the boundaries of disciplinary fields, rhetorical invasions, the in- terface of conceptual and scientific languages, and geomorphic and geopolitical interventions. Critical Climate Change is oriented, in this general manner, toward the epistemo-political mutations that correspond to the temporalities of terrestrial mutation. Immersion Into Noise Joseph Nechvatal OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS An imprint of MPublishing – University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, 2011 First edition published by Open Humanities Press 2011 Freely available online at http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.9618970.0001.001 Copyright © 2011 Joseph Nechvatal This is an open access book, licensed under the Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. Under this license, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy this book so long as the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or similar license. -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

World Literature for the Wretched of the Earth: Anticolonial Aesthetics

W!"#$ L%&'"(&)"' *!" &+' W"'&,+'$ !* &+' E("&+ Anticolonial Aesthetics, Postcolonial Politics -. $(.%'# '#(/ Fordham University Press .'0 1!"2 3435 Copyright © 3435 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Visit us online at www.fordhampress.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available online at https:// catalog.loc.gov. Printed in the United States of America 36 33 35 7 8 6 3 5 First edition C!"#$"#% Preface vi Introduction: Impossible Subjects & Lala Har Dayal’s Imagination &' B. R. Ambedkar’s Sciences (( M. K. Gandhi’s Lost Debates )* Bhagat Singh’s Jail Notebook '+ Epilogue: Stopping and Leaving &&, Acknowledgments &,& Notes &,- Bibliography &)' Index &.' P!"#$%" In &'(&, S. R. Ranganathan, an unknown literary scholar and statistician from India, published a curious manifesto: ! e Five Laws of Library Sci- ence. ) e manifesto, written shortly a* er Ranganathan’s return to India from London—where he learned to despise, among other things, the Dewey decimal system and British bureaucracy—argues for reorganiz- ing Indian libraries. -

Terrorism in the Name of Religion: with Special Reference to Islam

Terrorism in the Name of Religion: With Special Reference to Islam Supervisor Researcher Dr. Fr. Tapan C. De Rozario Shah Mohammad Jonayed Associate Professor Masters of Philosophy (M.Phil.) Department of World Religions and Culture Registration No: 38 University of Dhaka Session: 2011-2012 Examination Roll Number: 2 Joining date: 17/07/2012 Department of World Religions and Culture University of Dhaka December,2018 Dhaka University Institutional Repository Terrorism in the Name of Religion: With Special Reference to Islam Thesis re-submitted to the Department of World Religions and Culture, University of Dhaka in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of Masters of Philosophy (M.Phil.) in World Religions and Culture. By Shah Mohammad Jonayed M.PhilResearcher Registration No: 38 Session: 2011-2012 Examination Roll Number: 2 Supervisor Dr. Fr. Tapan C. De Rozario Associate Professor Department of World Religions and Culture University of Dhaka Department of World Religions and Culture University of Dhaka December, 2018 Dhaka University Institutional Repository Terrorism in the Name of Religion: With Special Reference to Islam Dhaka University Institutional Repository Preface All religions preach the gospel of love and it is the foundation of human existence. Without peace, justice and love nations cannot develop, and man- kind can enjoy neither happiness nor tranquility. In order to achieve social stability and world peace, there must be impartiality and harmonious living among nations, among political factions, among ethnic groups, and among religions. It is clear that peace is a divine prize that may come by the way of justice not by the terrorism. If there is religious terrorism there isn’t peace. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

Challenges to INTERNAL SECURITY of India Third Edition About the Authors

Challenges to INTERNAL SECURITY of India Third Edition About the Authors Ashok Kumar has completed his B.Tech, and M Tech. from Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Delhi. He joined Indian Police Service (IPS) in 1989 and has served in various challenging assignments in UP and Uttarakhand. He has also served in CRPF and BSF on deputation basis. Presently, he is posted as Director General, Crime, Law & Order, Uttarakhand. Before this assignment , he was Chief of Intelligence & Security, Uttarakhand. He received the UN Medal for serving in strife-torn Kosovo in 2001. He was awarded the Indian Police Medal for Meritorious Services in 2006 and President’s Police Medal for Distinguished Services in 2013. He has authored a path-breaking book titled ‘Human in Khaki’, which received GB Pant Award from Bureau of Police Research & Development (BPR&D), MHA. Recently, he has authored two more books, ‘Cracking Civil Services -The Open Secret’ and ‘Ethics for Civil Services’. Vipul Anekant has completed his B.Tech, from Malaviya National Institute of Technology (MNIT), Jaipur. He was a student of Tata Institute at Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai. He joined DANIPS in 2012. Presently, he is posted as Sub-Divisional Police Officer, Khanvel, Union Territory of Dadra & Nagar Haveli. Challenges to INTERNAL SECURITY of India Third Edition Ashok Kumar, IPS DG Crime, Law & Order, Uttarakhand Vipul, DANIPS SDPO, Dadra & Nagar Haveli McGraw Hill Education (India) Private Limited Published by McGraw Hill Education (India) Private Limited 444/1, Sri Ekambara Naicker Industrial Estate, Alapakkam, Porur, Chennai - 600 116 Challenges to Internal Security of India, 3e Copyright © 2019 by McGraw Hill Education (India) Private Limited. -

On the Auto Body, Inc

FINAL-1 Sat, Oct 14, 2017 7:52:52 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of October 21 - 27, 2017 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH $ 00 OFF 3 ANY CAR WASH! EXPIRES 10/31/17 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnetts H1artnett x 5” On the Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 run DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 Emma Dumont stars 15 WATER STREET in “The Gifted” DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Now that their mutant abilities have been revealed, teenage siblings must go on the lam in a new episode of “The Gifted,” airing Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 Monday. ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents Massachusetts’ First Credit Union • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents Located at 370 Highland Avenue, Salem John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks St. Jean's Credit Union • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3” With 35 years experience on the North Serving over 15,000 Members •3 A Partx 3 of your Community since 1910 Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful Supporting over 60 Non-Profit Organizations & Programs The LawOffice of Serving the Employees of over 40 Businesses STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Auto • Homeowners 978.739.4898 978.219.1000 • www.stjeanscu.com Business -

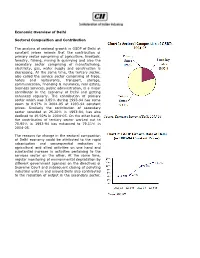

Economic Overview of Delhi Sectoral Composition and Contribution the Analysis of Sectoral Growth in GSDP of Delhi at Constant Pr

Economic Overview of Delhi Sectoral Composition and Contribution The analysis of sectoral growth in GSDP of Delhi at constant prices reveals that the contribution of primary sector comprising of agriculture, livestock, forestry, fishing, mining & quarrying and also the secondary sector comprising of manufacturing, electricity, gas, water supply and construction is decreasing. At the same time, the tertiary sector, also called the service sector comprising of trade, hotels and restaurants, transport, storage, communication, financing & insurance, real estate, business services, public administration, is a major contributor in the economy of Delhi and getting enhanced regularly. The contribution of primary sector which was 3.85% during 1993-94 has come down to 0.97% in 2004-05 at 1993-94 constant prices. Similarly the contribution of secondary sector recorded at 25.20% in 1993-94, has also declined to 19.92% in 2004-05. On the other hand, the contribution of tertiary sector worked out to 70.95% in 1993-94 has enhanced to 79.11% in 2004-05. The reasons for change in the sectoral composition of Delhi economy could be attributed to the rapid urbanisation and consequential reduction in agricultural and allied activities on one hand and substantial increase in activities pertaining to the services sector on the other. At the same time, regular monitoring of environmental degradation by different government agencies on the directives of Supreme Court and subsequent closing of polluting industrial units in and around Delhi also contributed to the reduction of output in the secondary sector. Delhi's service sector has expanded due in part to the large skilled English-speaking workforce that has attracted many multinational companies. -

Central University of Punjab, Bathinda, Punjab

Central University of Punjab, Bathinda, Punjab Course Scheme For M.A. (History) 1 CENTRE FOR SOUTH AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES (Including Historical Studies) Course structure-M.A. IN HISTORY % Weightage Semester I Marks Paper Course Title L T P Cr A B C D E Code HST. 501 Research F 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 Methodology HST. 503 Indian Political C 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 Thought HST. 504 Pre-History and C 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 Proto-History of India HST. 505 Ancient India C 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 (600BCE-300CE) HST. XXX Elective Course I E* 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 IDC. XXX Inter- E 2 0 0 2 15 10 10 15 50 Disciplinary/Open (O)** Elective HST. 599 Seminar C 0 0 0 2 15 10 10 15 50 TOTAL SEM I - 24 24 - 600 Elective Courses (Opt any one courses within the department) HST. 511 Art and Architecture E* 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 of Ancient India HST. 512 Early State and E* 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 Society in Ancient India Interdisciplinary Course/Open Elective Offered (For other Centers) HST. 521 Harrappan E 2 0 0 2 15 10 10 15 50 Civilization (O)** HST. 522 Religion in Ancient E 2 0 0 2 15 10 10 15 50 India (O)** 2 Semester II % Weightage Marks Paper Course Title L T P Cr A B C D E Code HST. -

Hearing Voices

FINAL-1 Sat, Dec 28, 2019 5:50:57 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of January 5 - 11, 2020 Hearing voices Jane Levy stars in “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 In an innovative, exciting departure from standard television fare, NBC presents “Zoe’s Extraordinary Playlist,” premiering Tuesday, Jan. 7. Jane Levy (“Suburgatory”) stars as the titular character, Zoey Clarke, a computer programmer whose extremely brainy, rigid nature often gets in the way of her ability to make an impression on the people around her. Skylar Astin (“Pitch Perfect,” 2012), Mary Steenburgen (“The Last Man on Earth”). John Clarence (“Luke Cage”), Peter Gallagher (“The O.C.”) and Lauren Graham (“Gilmore Girls”) also star. WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS ✦ 40 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLEWANTED1 x 3” We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC SELLBUYTRADEINSPECTIONS Score More CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car Sales This Winter at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA CALL (978)946-2000 TO ADVERTISE PRINT • DIGITAL • MAGAZINE • DIRECT MAIL Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com 978-851-3777 WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Dec 28, 2019 5:50:58 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 Sports Highlights Kingston CHANNEL Atkinson Sunday 11:00 p.m. -

Ecstatic Encounters Ecstatic Encounters

encounters ecstatic encounters ecstatic ecstatic encounters Bahian Candomblé and the Quest for the Really Real Mattijs van de Port AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Ecstatic Encounters Bahian Candomblé and the Quest for the Really Real Mattijs van de Port AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Layout: Maedium, Utrecht ISBN 978 90 8964 298 1 e-ISBN 978 90 4851 396 3 NUR 761 © Mattijs van de Port / Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2011 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents PREFACE / 7 INTRODUCTION: Avenida Oceânica / 11 Candomblé, mystery and the-rest-of-what-is in processes of world-making 1 On Immersion / 47 Academics and the seductions of a baroque society 2 Mysteries are Invisible / 69 Understanding images in the Bahia of Dr Raimundo Nina Rodrigues 3 Re-encoding the Primitive / 99 Surrealist appreciations of Candomblé in a violence-ridden world 4 Abstracting Candomblé / 127 Defining the ‘public’ and the ‘particular’ dimensions of a spirit possession cult 5 Allegorical Worlds / 159 Baroque aesthetics and the notion of an ‘absent truth’ 6 Bafflement Politics / 183 Possessions, apparitions and the really real of Candomblé’s miracle productions 5 7 The Permeable Boundary / 215 Media imaginaries in Candomblé’s public performance of authenticity CONCLUSIONS Cracks in the Wall / 249 Invocations of the-rest-of-what-is in the anthropological study of world-making NOTES / 263 BIBLIOGRAPHY / 273 INDEX / 295 ECSTATIC ENCOUNTERS · 6 Preface Oh! Bahia da magia, dos feitiços e da fé. -

Film Shooting Manual for Shooting of Films in Delhi

FILM SHOOTING MANUAL FOR SHOOTING OF FILMS IN DELHI Delhi Tourism Govt. of NCT of Delhi 1 Message The capital city, Delhi, showcases an ancient culture and a rapidly modernizing country. It boasts of 170 notified monuments, which includes three UNESCO World Heritage Sites as well as many contemporary buildings. The city is a symbol of the country’s rich past and a thriving present. The Capital is a charming mix of old and new. Facilities like the metro network, expansive flyovers, the swanky airport terminal and modern high- rise buildings make it a world-class city. Glancing through the past few years, it is noticed that Bollywood has been highly responsive of the offerings of Delhi. More than 200 films have been shot here in the past five years. Under the directives issued by Ministry of Tourism and Ministry of I & B, the Govt. of NCT of Delhi has nominated Delhi Tourism & Transportation Development Corporation Ltd. as the nodal agency for facilitating shooting of films in Delhi and I have advised DTTDC to incorporate all procedures in the Manual so that Film Fraternity finds it user- friendly. I wish Delhi Tourism the best and I am confident that they will add a lot of value to the venture. Chief Secretary, Govt. of Delhi 2 Message Delhi is a city with not just rich past glory as the seat of empire and magnificent monuments, but also in the rich and diverse culture. The city is sprinkled with dazzling gems: captivating ancient monuments, fascinating museums and art galleries, architectural wonders, a vivacious performing-arts scene, fabulous eateries and bustling markets.