PDF of Listening Into Others

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS, FEATURE DOCUMENTARIES AND MADE-FOR-TELEVISION FILMS, 1945-2011 COMPILED BY PAUL GRATTON MAY, 2012 2 5.Fast Ones, The (Ivy League Killers) 1945 6.Il était une guerre (There Once Was a War)* 1.Père Chopin, Le 1960 1946 1.Canadians, The 1.Bush Pilot 2.Désoeuvrés, Les (The Mis-Works)# 1947 1961 1.Forteresse, La (Whispering City) 1.Aventures de Ti-Ken, Les* 2.Hired Gun, The (The Last Gunfighter) (The Devil’s Spawn) 1948 3.It Happened in Canada 1.Butler’s Night Off, The 4.Mask, The (Eyes of Hell) 2.Sins of the Fathers 5.Nikki, Wild Dog of the North 1949 6.One Plus One (Exploring the Kinsey Report)# 7.Wings of Chance (Kirby’s Gander) 1.Gros Bill, Le (The Grand Bill) 2. Homme et son péché, Un (A Man and His Sin) 1962 3.On ne triche pas avec la vie (You Can’t Cheat Life) 1.Big Red 2.Seul ou avec d’autres (Alone or With Others)# 1950 3.Ten Girls Ago 1.Curé du village (The Village Priest) 2.Forbidden Journey 1963 3.Inconnue de Montréal, L’ (Son Copain) (The Unknown 1.A tout prendre (Take It All) Montreal Woman) 2.Amanita Pestilens 4.Lumières de ma ville (Lights of My City) 3.Bitter Ash, The 5.Séraphin 4.Drylanders 1951 5.Have Figure, Will Travel# 6.Incredible Journey, The 1.Docteur Louise (Story of Dr.Louise) 7.Pour la suite du monde (So That the World Goes On)# 1952 8.Young Adventurers.The 1.Etienne Brûlé, gibier de potence (The Immortal 1964 Scoundrel) 1.Caressed (Sweet Substitute) 2.Petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre, La (Little Aurore’s 2.Chat dans -

Minnesota Department of Commerce Telecommunications Access Minnesota

MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE TELECOMMUNICATIONS ACCESS MINNESOTA MINNESOTA RELAY AND TELEPHONE EQUIPMENT DISTRIBUTION PROGRAM 2007 ANNUAL REPORT TO THE MINNESOTA PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION DOCKET NO. P999/M-08-2 JANUARY 31, 2008 Department of Commerce – Telecommunications Access Minnesota 85 7th Place East, Suite 600 St. Paul, Minnesota 55101-3165 [email protected] 651-297-8941 / 1-800-657-3599 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................................1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & PROGRAM HISTORY .........................................................2 TELECOMMUNICATIONS ACCESS MINNESOTA (TAM) ............................................4 TAM Administration ..........................................................................................................4 TAM Funding.....................................................................................................................5 Population Served ..............................................................................................................6 Role of the Public Utilities Commission............................................................................7 MINNESOTA RELAY PROGRESS.....................................................................................7 Notification to Interexchange Carriers Regarding Access to Services Through TRS....7 Notification to Carriers Regarding Public Access to Information...................................8 Emergency Preparedness...................................................................................................9 -

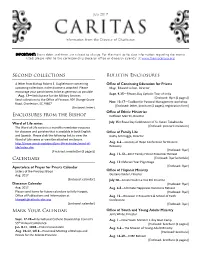

Second Collections Enclosures from The

July 2017 Information from the Diocese of Charleston IMPORTANT: Event dates and times are subject to change. For the most up-to-date information regarding the events listed, please refer to the corresponding diocesan office or diocesan calendar at www.themiscellany.org. Second collections Bulletin Enclosures A letter from Bishop Robert E. Guglielmone concerning Office of Continuing Education for Priests upcoming collections in the diocese is attached. Please Msgr. Edward Lofton, Director encourage your parishioners to be as generous as possible. Sept. 9-25—Fifteen-Day Catholic Tour of India Aug. 13—Archdiocese for the Military Services [Enclosed: flyer (2 pages)] Send collections to the Office of Finance, 901 Orange Grove Nov. 13-17—Toolbox for Pastoral Management workshop Road, Charleston, SC 29407. [Enclosed: letter, brochure (2 pages), registration form] [Enclosed: letter] Office of Ethnic Ministries Enclosures from the Bishop Kathleen Merritt, Director Word of Life series July 15—Feast Day Celebration of St. Kateri Tekakwitha [Enclosed: postcard invitation] The Word of Life series is a monthly newsletter resource for dioceses and parishes that is available in both English Office of Family Life and Spanish. Please click the following link to view the Kathy Schmugge, Director Word of Life series or view the attached enclosure. http://www.usccb.org/about/pro-life-activities/word-of- Aug. 4-6—Journey of Hope Conference for Divorce life/index.cfm Recovery [Enclosed: newsletter (3 pages)] [Enclosed: flyer] Aug. 11-12—2017 Family Honor Presenter Retreat Calendars [Enclosed: flyer/schedule] Aug. 13—Marian Year Pilgrimage Apostolate of Prayer for Priests Calendar [Enclosed: flyer] Sisters of the Precious Blood Office of Hispanic Ministry Aug. -

Kenyon Collegian College Archives

Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange The Kenyon Collegian College Archives 9-22-1977 Kenyon Collegian - September 22, 1977 Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/collegian Recommended Citation "Kenyon Collegian - September 22, 1977" (1977). The Kenyon Collegian. 970. https://digital.kenyon.edu/collegian/970 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College Archives at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kenyon Collegian by an authorized administrator of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Mf8llt Colleg Established IS56 3 Volume CV, Number Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio 43022 Thursday, September 22, 1977 Untangling Council Blasts New Fees; Traffic Woes Backs Social Board Duties By LINDSAY C. BROOKS ' WIN'CEK By CHRIS Student Council Sunday night I ! passed a unanimous resolution revisions effective this Despite new forming a subcommittee to look into in code, traffic i school year the traffic the new registration fee for courses likely continue to i fines shall most dropped after the first two weeks among both of t to rouse feathers students the semester, and discussed Social I 5 and the administration. Arnold Board's function as a financial Director of Security, feels Hamilton, source for fraternity-sponsore- d grievance-provokin- g r that "it's the main activities, as well as the possibility of problem between the a seven-ivee- k break at Christmas. students and my department, and The committee will find out the will probably continue to be so." L philosophy behind the fee structure; P whether it is a handling fee or a Chief Security Officer Arnie One junior expressed strong Hamilton on the job penalty fee. -

Immersion Into Noise

Immersion Into Noise Critical Climate Change Series Editors: Tom Cohen and Claire Colebrook The era of climate change involves the mutation of systems beyond 20th century anthropomorphic models and has stood, until recent- ly, outside representation or address. Understood in a broad and critical sense, climate change concerns material agencies that im- pact on biomass and energy, erased borders and microbial inven- tion, geological and nanographic time, and extinction events. The possibility of extinction has always been a latent figure in textual production and archives; but the current sense of depletion, decay, mutation and exhaustion calls for new modes of address, new styles of publishing and authoring, and new formats and speeds of distri- bution. As the pressures and re-alignments of this re-arrangement occur, so must the critical languages and conceptual templates, po- litical premises and definitions of ‘life.’ There is a particular need to publish in timely fashion experimental monographs that redefine the boundaries of disciplinary fields, rhetorical invasions, the in- terface of conceptual and scientific languages, and geomorphic and geopolitical interventions. Critical Climate Change is oriented, in this general manner, toward the epistemo-political mutations that correspond to the temporalities of terrestrial mutation. Immersion Into Noise Joseph Nechvatal OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS An imprint of MPublishing – University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, 2011 First edition published by Open Humanities Press 2011 Freely available online at http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.9618970.0001.001 Copyright © 2011 Joseph Nechvatal This is an open access book, licensed under the Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. Under this license, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy this book so long as the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or similar license. -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

Paul Schoenfield's' Refractory'method of Composition: a Study Of

Paul Schoenfield's 'Refractory' Method of Composition: A Study of Refractions and Sha’atnez A document submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music by DoYeon Kim B.M., College-Conservatory of Music of The University of Cincinnati, 2011 M.M., Eastman School of Music of The University of Rochester, 2013 Committee Chair: Professor Yehuda Hanani Abstract Paul Schoenfield (b.1947) is a contemporary American composer whose works draw on jazz, folk music, klezmer, and a deep knowledge of classical tradition. This document examines Schoenfield’s characteristic techniques of recasting and redirecting preexisting musical materials through diverse musical styles, genres, and influences as a coherent compositional method. I call this method ‘refraction’, taking the term from the first of the pieces I analyze here: Refractions, a trio for Clarinet, Cello and Piano written in 2006, which centers on melodies from Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro). I will also trace the ‘refraction’ method through Sha’atnez, a trio for Violin, Cello and Piano (2013), which is based on two well-known melodies: “Pria ch’io l’impegno” from Joseph Weigl’s opera L’amor marinaro, ossia il corsaro (also known as the “Weigl tune,” best known for its appearance in the third movement of Beethoven’s Trio for Piano, Clarinet, and Cello in B-flat Major, Op.11 (‘Gassenhauer’)); and the Russian-Ukrainian folk song “Dark Eyes (Очи чёрные).” By tracing the ‘refraction’ method as it is used to generate these two works, this study offers a unified approach to understanding Schoenfield’s compositional process; in doing so, the study both makes his music more accessible for scholarly examination and introduces enjoyable new works to the chamber music repertoire. -

On the Auto Body, Inc

FINAL-1 Sat, Oct 14, 2017 7:52:52 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of October 21 - 27, 2017 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH $ 00 OFF 3 ANY CAR WASH! EXPIRES 10/31/17 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnetts H1artnett x 5” On the Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 run DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 Emma Dumont stars 15 WATER STREET in “The Gifted” DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Now that their mutant abilities have been revealed, teenage siblings must go on the lam in a new episode of “The Gifted,” airing Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 Monday. ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents Massachusetts’ First Credit Union • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents Located at 370 Highland Avenue, Salem John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks St. Jean's Credit Union • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3” With 35 years experience on the North Serving over 15,000 Members •3 A Partx 3 of your Community since 1910 Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful Supporting over 60 Non-Profit Organizations & Programs The LawOffice of Serving the Employees of over 40 Businesses STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Auto • Homeowners 978.739.4898 978.219.1000 • www.stjeanscu.com Business -

Qwhjudwlrqv Zlwk ([Whuqdo 6\Vwhpv

Integrations with External Systems 1 CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION The information herein is the property of Ex Libris Ltd. or its affiliates and any misuse or abuse will result in economic loss. DO NOT COPY UNLESS YOU HAVE BEEN GIVEN SPECIFIC WRITTEN AUTHORIZATION FROM EX LIBRIS LTD. This document is provided for limited and restricted purposes in accordance with a binding contract with Ex Libris Ltd. or an affiliate. The information herein includes trade secrets and is confidential. DISCLAIMER The information in this document will be subject to periodic change and updating. Please confirm that you have the most current documentation. There are no warranties of any kind, express or implied, provided in this documentation, other than those expressly agreed upon in the applicable Ex Libris contract. This information is provided AS IS. Unless otherwise agreed, Ex Libris shall not be liable for any damages for use of this document, including, without limitation, consequential, punitive, indirect or direct damages. Any references in this document to third‐party material (including third‐party Web sites) are provided for convenience only and do not in any manner serve as an endorsement of that third‐ party material or those Web sites. The third‐party materials are not part of the materials for this Ex Libris product and Ex Libris has no liability for such materials. TRADEMARKS Ex Libris, the Ex Libris logo, Alma, campusM, Esploro, Leganto, Primo, Rosetta, Summon, ALEPH 500, SFX, SFXIT, MetaLib, MetaSearch, MetaIndex and other Ex Libris products and services referenced herein are trademarks of Ex Libris, and may be registered in certain jurisdictions. -

Hearing Voices

FINAL-1 Sat, Dec 28, 2019 5:50:57 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of January 5 - 11, 2020 Hearing voices Jane Levy stars in “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 In an innovative, exciting departure from standard television fare, NBC presents “Zoe’s Extraordinary Playlist,” premiering Tuesday, Jan. 7. Jane Levy (“Suburgatory”) stars as the titular character, Zoey Clarke, a computer programmer whose extremely brainy, rigid nature often gets in the way of her ability to make an impression on the people around her. Skylar Astin (“Pitch Perfect,” 2012), Mary Steenburgen (“The Last Man on Earth”). John Clarence (“Luke Cage”), Peter Gallagher (“The O.C.”) and Lauren Graham (“Gilmore Girls”) also star. WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS ✦ 40 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLEWANTED1 x 3” We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC SELLBUYTRADEINSPECTIONS Score More CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car Sales This Winter at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA CALL (978)946-2000 TO ADVERTISE PRINT • DIGITAL • MAGAZINE • DIRECT MAIL Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com 978-851-3777 WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Dec 28, 2019 5:50:58 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 Sports Highlights Kingston CHANNEL Atkinson Sunday 11:00 p.m. -

Sculpture Milwaukee Fact Sheet

Contact: Rachel Farina Ellingsen Brady Advertising 414.224.9424 Kristin Settle VISIT Milwaukee 414.287.6230 Sculpture Milwaukee Fact Sheet DESCRIPTION: Sculpture Milwaukee, a free outdoor urban sculpture experience in downtown Milwaukee, will be on view June 1 – Oct. 22. Led by Steve Marcus, chairman of the board of The Marcus Corporation, and curated by Russell Bowman, an art consultant based in Chicago and former Director of the Milwaukee Art Museum, the installation features 22 sculptures by 21 artists. Works by Donald Baechler, Lynda Benglis, Chakaia Booker, Deborah Butterfield, Santiago Calatrava, Saint Clair Cemin, Tony Cragg, Jim Dine, Paul Druecke, Michelle Grabner, John Henry, Sol LeWitt, Dennis Oppenheim, Tom Otterness, Will Ryman, Alison Saar, Joel Shapiro, Jessica Stockholder, Tony Tasset, Manolo Valdes and Jason S. Yi are showcased. Sculpture Milwaukee is slated to be an annual exhibition, highlighting new artists and works each year. Sculptures within the installation are available for purchase. A percentage of the commission of each sale will be reinvested into Sculpture Milwaukee, a nonprofit initiative managed by Milwaukee Downtown, Business Improvement District #21, for continuation of the program into future years. PROGRAMMING: A variety of activities and programs ranging from tours to artist lectures will be held throughout the installation. For the most up-to-date information, visit www.sculpturemilwaukee.com or call 414-220-4700. WHEN: June 1 through Oct. 22, 2017 LOCATION: Sculpture Milwaukee is positioned along downtown Milwaukee’s Wisconsin Avenue. The one-mile stretch begins at O’Donnell Park, near the Milwaukee Art Museum and Mark di Suvero’s “The Calling”, and concludes at 6th Street, adjacent to the Wisconsin Center. -

Ecstatic Encounters Ecstatic Encounters

encounters ecstatic encounters ecstatic ecstatic encounters Bahian Candomblé and the Quest for the Really Real Mattijs van de Port AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Ecstatic Encounters Bahian Candomblé and the Quest for the Really Real Mattijs van de Port AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Layout: Maedium, Utrecht ISBN 978 90 8964 298 1 e-ISBN 978 90 4851 396 3 NUR 761 © Mattijs van de Port / Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2011 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents PREFACE / 7 INTRODUCTION: Avenida Oceânica / 11 Candomblé, mystery and the-rest-of-what-is in processes of world-making 1 On Immersion / 47 Academics and the seductions of a baroque society 2 Mysteries are Invisible / 69 Understanding images in the Bahia of Dr Raimundo Nina Rodrigues 3 Re-encoding the Primitive / 99 Surrealist appreciations of Candomblé in a violence-ridden world 4 Abstracting Candomblé / 127 Defining the ‘public’ and the ‘particular’ dimensions of a spirit possession cult 5 Allegorical Worlds / 159 Baroque aesthetics and the notion of an ‘absent truth’ 6 Bafflement Politics / 183 Possessions, apparitions and the really real of Candomblé’s miracle productions 5 7 The Permeable Boundary / 215 Media imaginaries in Candomblé’s public performance of authenticity CONCLUSIONS Cracks in the Wall / 249 Invocations of the-rest-of-what-is in the anthropological study of world-making NOTES / 263 BIBLIOGRAPHY / 273 INDEX / 295 ECSTATIC ENCOUNTERS · 6 Preface Oh! Bahia da magia, dos feitiços e da fé.