Education, University of Wollongong, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Minister's and Secretary's Awards for Excellence Public Education Foundation 3 Award Recipients

We Give Life-Changing Scholarships 2019 Minister’s and Secretary’s Awards for Excellence MC Jane Caro Welcome Acknowledgement of Country Takesa Frank – Ulladulla High School Opening Remarks It’s my great pleasure to welcome you to the 2019 Minister’s David Hetherington and Secretary’s Awards for Excellence. These Awards showcase the wonderful people and extraordinary talent across NSW public education – schools, students, teachers, Minister’s Remarks employees and parents. The Hon Sarah Mitchell MLC Order of Proceedings Minister for Education and Early Childhood The Public Education Foundation’s mission is to celebrate the Learning best of public schooling, and these Awards are a highlight of our annual calendar. The Foundation is proud to host the Awards on behalf of The Honourable Sarah Mitchell MLC, Minister for Tuesday 27 August 2019 Presentations Education and Early Childhood Learning and Mr Mark Scott AO, 4-6pm Minister’s Award for Excellence in Secretary of the NSW Department of Education. Student Achievement Lower Town Hall, Minister’s Award for Excellence in Teaching You’ll hear today about outstanding achievements and breakthrough initiatives from across the state, from a new data Sydney Town Hall sharing system at Bankstown West Public School to a STEM Performance Industry School Partnership spanning three high schools across Listen With Your Heart regional NSW. Performed by Kyra Pollard Finigan School of Distance Education The Foundation recently celebrated our 10th birthday and to mark the occasion, we commissioned a survey of all our previous scholarship winners. We’re proud to report that over Secretary’s Remarks 98% of our eligible scholars have completed Year 12, and of Mark Scott AO these, 72% have progressed onto university. -

West Wyalong High School Newsletter

West Wyalong High School 30 Dumaresq Street West Wyalong NSW 2671 T 02 69722700 F 02 69722236 Newsletter E [email protected] SINCERITY MONDAY OCTOBER 30 2017 TERM 4 WEEK 4 [email protected]. We value your opinion and we appreciate the ongoing support of our families and the local community. STRIVING FOR SCHOOL EXCELLENCE It has been a hectic start to the term with many TERM 4 CALENDAR additional opportunities for our students. Mr Lees co- ordinated a great experience for fourteen students WEEK 4 who successfully completed an intense shearing Year 12 Work Placement 30 Oct-3 Nov school. All of these students gained a valuable insight Penrith Exchange Program into the skills and demands of this career. Girls CHS Basketball ‘Final 8’ 31 Oct – 2 Nov at Terrigal Mrs Barnes and her Year 9/10 Food Technology students participated in a catering experience for the Wednesday 1 Nov CHS Water Polo – Albury 10-year anniversary of the Lake Cowal Foundation. WEEK 5 The food and service was greatly appreciated by the Thursday 9 Nov Creative Minds Exhibition eighty plus visitors to the conservation centre. Evolution Mining, LCF and LCCC are great supporters of our school and we value the work of RETURN OF TROPHIES Sally Russell and Mal Carnegie in providing exciting As the end of year fast approaches, could all West environmental experiences for our students. Wyalong High School academic and sporting trophies please be returned to the school as soon as possible. Ms Maslin transported our Rotary exchange students to Forbes on Saturday for their weeklong visit to Penrith. -

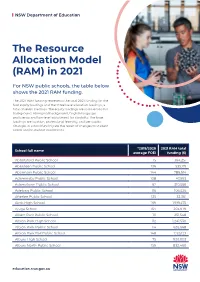

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 347,551 Alma Public -

Winter Edition – No: 42 2013

Winter Edition – No: 42 2013 What is this dude on about? President: Carl Chirgwin Griffith High School Coolah St, Griffith NSW 2680 02 6962 1711 (w) www.nswaat.org.au 02 6964 1465 (f) ABN Number: 81 639 285 642 [email protected] Secretary: Jade Smith Dunedoo Central School, Digilah St Dunedoo NSW 2844 02 6375 1489 (w) [email protected] President’s Report 2 NSWAAT turns 40 5 Treasurer: Leanne Sjollema State Conference Report 6 McCarthy Catholic College PO Box 3486 Association Membership 9 West Tamworth NSW 2340 NSWAAT Facebook Group 13 [email protected] Livestock Handlin Workshop 17 Technology & Communication: Life Membership and JA Sutherland Awardees 23 Ian Baird Murrumburrah, NSW State Agriculture Advisory Group (SAAG) Report 29 [email protected] First Place HSC Primary Industries 2012 31 Nikia Waters Australian Curriculum: Technologies 32 Hillston Central School [email protected] Agriculture at Coleambally Central School 33 Georgina Price Primary Industries Activity: Learning about Weather 38 Coleambally Central School NAAE Conference 40 [email protected] Australian National Field Days 44 BAAT Editor: PIEF June Newsletter 46 Graham Quintal Farm Case Studies Project CRC Contacts 52 [email protected] th NSWAAT 40 Birthday 53 Email List Manager: Vermiculture 54 Justin Connors Manilla Central School Free Study Guides 56 [email protected] Coles Junior Landcare Garden Grants 58 SAAG Reps: More Agricultural Scientists needed 60 Graeme Harris (Farrer) Agrifood Career Access Pathways 62 [email protected] Schools in the News 64 Rob Henderson (Tomaree High) [email protected] Upcoming Events 85 Phil Armour (Yass High) Snippets 86 [email protected] Archivists: Tony Butler (Tumut High) [email protected] Phil Hurst (Hawkesbury) [email protected] Nigel Cox (Singleton) [email protected] www.nswaat.org.au 1 Get on the BAAT bandwagon Being President of this great and unique association of educators is my biggest achievement in education thus far. -

Deni High News

Issue 10 - Term 4 - Week 4 Friday, 8 December 2019 Deni High News Principal: Kym Orman (Relieving) Deputy Principals: Peter Astill and Robyn Richards Harfleur Street, Deniliquin NSW 2710 T: 5881 1211 F: 5881 5115 E: [email protected] W: www.deniliquin-h.schools.nsw.gov.au Issue 10- Term 4 - Week 4 Friday, 8 November 2019 Principal Report such as rare and exotic wildlife and plants, The commencement of term 4 was celebrated with different cultures and tours/visits to iconic the highly successful and entertaining school buildings and areas. production, The Wizard from Oz. Congratulations to Social skills - Getting out of the classroom the whole team on a polished performance. gives children an opportunity to spend time with As a school the opportunities both in and beyond the each other in a new environment without the classroom are outstanding. Much planning has structure of the classroom. School excursions occurred for the Year 11 Melbourne excursion, Year often require students to spend time in small 9 Anglesea excursion, Year 10 Sydney excursion, groups, observing, chatting and learning. Duke of Edinburgh experience, Great Vic Bike Ride, Thank you to staff who have planned, supported, farm vehicle safety program and driver education attended and supervised these events. opportunity. The school encourages the practice of As the term progresses assessments and reporting excursions as it clearly adds reality to learning and procedure are well underway and we look forward to enriches classroom activities. deeper educational celebrating student successes on 17 December at experiences, increases understanding, motivation our formal assembly and presentation night. -

ABORIGINAL and HISTORIC HERITAGE ASSESSMENT Wagga

View of Wagga Wagga Main City Levee. ABORIGINAL AND HISTORIC HERITAGE ASSESSMENT Wagga Wagga Levee Upgrade Project November 2012 Report Prepared by OzArk Environmental & Heritage Management Pty Ltd for GHD Wagga on behalf of Wagga Wagga City Council DOCUMENT CONTROLS Proponent Wagga Wagga City Council Client GHD Wagga Project No / Purchase Order No Document Description Archaeological Assessment: Wagga Wagga LGA, NSW. Name Signed Date Clients Reviewing Officer Clients representative managing this document OzArk Person(s) managing this document Mr Reuben Robinson Mr Josh Noyer Location OzArk Job No. 751 Document Status V1.0 Date Draft V1.1 Author to Editor OzArk 1st Internal V1 JN to PJC (Series V1.X = OzArk internal edits) V1.1 BC Edit 20/9/12 Draft V2.0 Report Draft for release to client V2.0 OzArk to client 21/9/12 (Series V2.X = OzArk and Client edits) V2.1 OzArk to client with edits 6/11/12 FINAL once latest version of draft approved by V3.0 OzArk released as FINAL 27.11.12 client Prepared For Prepared By Reuben Robinson Joshua Noyer Senior Ecologist / Environmental Scientist Archaeologists GHD OzArk Environmental & Heritage Management P 02 6923 7418 Pty. Limited [email protected] P 02 6882 0118 F 02 6882 6030 Email: [email protected] COPYRIGHT © OzArk Environmental & Heritage Management Pty Ltd, 2012 and © GHD Wagga 2012 All intellectual property and copyright reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, 1968, no part of this report may be reproduced, transmitted, stored in a retrieval system or adapted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without written permission. -

Acacia Program Scholarship –Rural

2022 INFORMATION SHEET ACACIA PROGRAM SCHOLARSHIP – RURAL NSW The Public Education Foundation’s Acacia Program Scholarship provides financial assistance and mentoring/career advice to high potential students, in need, attending schools in specific schools or school regions in Rural NSW (See basic eligibility section for complete list of eligible schools). The Acacia Program scholarship was designed to assist students in need who may otherwise not have the opportunity to reach their full potential. The scholarships are available to eligible students currently enrolled in Year 10 in the listed schools, with one scholarship available in each region. The scholarship has been established to enable alumni of Australian public schools to give back to their school region, and to public education more broadly, through scholarships, mentoring and advocacy. The scholarships aims to highlight to students the diversity of careers and possibilities available to them through the Australians who sponsor the award and have access to this network. We hope to show students: • Examples of people who have succeeded who come from where they come from, who they can relate to and see themselves in; and • Examples of people who are involved in a wide variety of careers and who are doing what they are interested in doing, to show them a path into the career they want. Each scholarship consists of a bursary of $1,000 per year for two years (total $2,000) to support the students’ studies whilst enrolled in high school, plus mentoring/career information opportunities with Acacia Fellow. The scholarship is to cover educational expenses such as: . Laptop, iPad or similar device . -

South Eastern Australia Temperate Woodlands

Conservation Management Zones of Australia South Eastern Australia Temperate Woodlands Prepared by the Department of the Environment Acknowledgements This project and its associated products are the result of collaboration between the Department of the Environment’s Biodiversity Conservation Division and the Environmental Resources Information Network (ERIN). Invaluable input, advice and support were provided by staff and leading researchers from across the Department of Environment (DotE), Department of Agriculture (DoA), the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and the academic community. We would particularly like to thank staff within the Wildlife, Heritage and Marine Division, Parks Australia and the Environment Assessment and Compliance Division of DotE; Nyree Stenekes and Robert Kancans (DoA), Sue McIntyre (CSIRO), Richard Hobbs (University of Western Australia), Michael Hutchinson (ANU); David Lindenmayer and Emma Burns (ANU); and Gilly Llewellyn, Martin Taylor and other staff from the World Wildlife Fund for their generosity and advice. Special thanks to CSIRO researchers Kristen Williams and Simon Ferrier whose modelling of biodiversity patterns underpinned identification of the Conservation Management Zones of Australia. Image Credits Front Cover: Yanga or Murrumbidgee Valley National Park – Paul Childs/OEH Page 4: River Red Gums (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) – Allan Fox Page 10: Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) – Trent Browning Page 16: Gunbower Creek – Arthur Mostead Page 19: Eastern Grey -

Spring Edition – No: 48

Spring Edition – No: 48 2015 Commonwealth Vocational Education Scholarship 2015. I was awarded with the Premier Teaching Scholarship in Vocational Education and Training for 2015. The purpose of this study tour is to analyse and compare the Vocational Education and Training (Agriculture/Horticulture/Primary Industries) programs offered to school students in the USA in comparison to Australia and how these articulate or prepare students for post school vocational education and training. I will be travelling to the USA in January 2016 for five weeks. While there, I will visit schools, farms and also attend the Colorado Agriculture Teachers Conference on 29-30th January 2016. I am happy to send a detailed report of my experiences and share what I gained during this study tour with all Agriculture teachers out there. On the 29th of August I went to Sydney Parliament house where I was presented with an award by the Minister of Education Adrian Piccoli. Thanks Charlie James President: Justin Connors Manilla Central School Wilga Avenue Manilla NSW 2346 02 6785 1185 www.nswaat.org.au [email protected] ABN Number: 81 639 285 642 Secretary: Carl Chirgwin Griffith High School Coolah St, Griffith NSW 2680 02 6962 1711 [email protected]. au Treasurer: Membership List 2 Graham Quintal Great Plant Resources 6 16 Finlay Ave Beecroft NSW 2119 NSWAAT Spring Muster 7 0422 061 477 National Conference Info 9 [email protected] Articles 13 Technology & Communication: Valuable Info & Resources 17 Ian Baird Young NSW Upcoming Agricultural -

Premier's Teacher Scholarships Alumni 2000

Premier’s Teacher Scholarships Alumni 2000 - 2016 Alumni – 2000 Premier’s American History Scholarships • Judy Adnum, Whitebridge High School • Justin Briggs, Doonside High School • Bruce Dennett, Baulkham Hills High school • Kerry John Essex, Kyogle High School • Phillip Sheldrick, Robert Townson High School Alumni – 2001 Premier’s American History Scholarships • Phillip Harvey, Shoalhaven Anglican School • Bernie Howitt, Narara Valley High School • Daryl Le Cornu, Eagle Vale High School • Brian Everingham, Birrong Girls High School • Jennifer Starink, Glenmore Park High School Alumni – 2002 Premier’s Westfield Modern History Scholarships • Julianne Beek, Narara Valley High School • Chris Blair, Woolgoolga High School • Mary Lou Gardam, Hay War Memorial High School • Jennifer Greenwell, Mosman High School • Jonathon Hart, Coffs Harbour Senior College • Paul Kiem, Trinity Catholic College • Ray Milton, Tomaree High School • Peter Ritchie, Wagga Wagga Christian College Premier’s Macquarie Bank Science Scholarships • Debbie Irwin, Strathfield Girls High School • Maleisah Eshman, Wee Waa High School • Stuart De Landre, Mt Kembla Environmental Education Centre • Kerry Ayre, St Joseph’s High School • Janine Manley, Mt St Patrick Catholic School Premier’s Special Education Scholarship • Amanda Morton, Belmore North Public School Premier’s English Literature Scholarships • Jean Archer, Maitland Grossman High School • Greg Bourne, TAFE NSW-Riverina Institute • Kathryn Edgeworth, Broken Hill High School • Lorraine Haddon, Quirindi High School -

Youth Mental Health Forum Post Event Report

2017 Youth Mental Health Forum Post Event Report Wagga Wagga, Murrumbidgee Region Details Author: Sarah Groves (Community Engagement Officer - headspace Wagga Wagga) Completed: 4th December 2017 Name: 2017 Youth Mental Health Forum Date: Tuesday the 6th of June 2017 Location: Mater Dei Primary School Hall, Wagga Wagga Attendees: 18 high schools, 160 students Facilitators: Burn Bright (https://www.burnbright.org.au/) Guest Speakers: Jarrad Hickmott (lived experience), Sarah Groves (mental health introduction) Q&A Panel: Sean Hodgins (Psychiatrist – Community Mental Health), Kylie Hamblin (Clinical Psychologist – headspace Wagga Wagga), Anne Egan (Psychologist – Department of Education), Jarrad Hickmott (lived experience), Troy Fisher (School Liaison Officer – NSW Police) Financial Sponsors: NSW Department of Education, Catholic Schools Office – diocese of Wagga Wagga, City of Wagga Wagga, Community Drug Action Team – Wagga Wagga, Charles Sturt University – Head of Campus Wagga Wagga 2017 Steering Committee Members . headspace Wagga Wagga . COMPACT . Catholic Schools Office – diocese of Wagga Wagga . TAFE NSW – Riverina . NSW Department of Education . Mission Australia . NSW Police . Anglicare NSW . Intereach . City of Wagga Wagga . Multicultural Council of Wagga Wagga . Relationships Australia Canberra & Region . Rural Advisory Mental Health Program – NSW Health . STARTTS . School-Link Overview Questions are often asked as to why young people may be disengaging from education. One potential answer is related to poor mental health, a significant barrier for young people meaningfully engaging in education1. To help address this, a local steering committee comprised of education providers, mental health professionals and a variety of community and youth service representatives, implemented the Youth Mental Health Forum (YMHF). The YMHF approach has been implemented in multiple locations across the Riverina over the last 5 years. -

P1207FR06-05.Pdf (PDF, 1.04MB)

RICE CRC FINAL RESEARCH REPORT P1207FR06/05 ISBN 1 876903 24 4 Title of Project : Hydro-climatic and Economic Evaluation of Seasonal Climate Forecasts for Risk Based Irrigation Management Project Reference number : 1207 Research Organisation Name : CSIRO Land and Water Principal Investigator Details : Name : Prof. Shahbaz Khan Address : CSIRO Land and Water Research Station Road GRIFFITH NSW 2680 Telephone contact : Tel: 02-6960 1500 Fax: 02-6960 1600 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Hydro-climatic and Economic Evaluation of Seasonal Climate Forecasts for Risk Based Irrigation Management Shahbaz Khan1, David Robinson1, Redha Beddek1, Butian Wang1, Dharma Dassanayake1, Tariq Rana1 1Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Private Bag 3 Griffith NSW 2680 Australia email: [email protected] http://www.clw.csiro.au/division/griffith Rice CRC Final Report – Project No 1207 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary 1 1. Background 2 1.1 Water in the Murrumbidgee Catchment 2 1.2 Annual irrigation water allocation in the Murrumbidgee Valley 3 1.3 Regression analysis to predict general security allocation levels 8 2. Objectives 10 3. Introductory technical information 11 3.1 Seasonal Climate Forecasting Methods 11 3.2 Studies to assess suitability of using SOI in Murrumbidgee 11 3.3 Studies to assess suitability of using SST in Murrumbidgee 19 4. Methodology 29 4.1 Model training and results 29 5. Results 31 5.1 Model R1: AAÆOA 31 5.2 Model R2: AAÆJA 33 5.3 Model R3: AASSTÆJA 36 6. Economic Evaluation of an End-of-Season Allocation Forecast 38 6.1 Methodology for economic analysis 38 6.2 Decision analysis 39 6.3 LP model assumptions and constraints 39 6.4 Results of economic analysis 41 6.5 Sensitivity analysis 46 7.