A Study on the Relationship Between Wiradjuri People and the Non-Indigenous Colonisers of Wagga Wagga 1830-1900

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Murrumbidgee Regional Fact Sheet

Murrumbidgee region Overview The Murrumbidgee region is home The river and national parks provide to about 550,000 people and covers ideal spots for swimming, fishing, 84,000 km2 – 8% of the Murray– bushwalking, camping and bird Darling Basin. watching. Dryland cropping, grazing and The Murrumbidgee River provides irrigated agriculture are important a critical water supply to several industries, with 42% of NSW grapes regional centres and towns including and 50% of Australia’s rice grown in Canberra, Gundagai, Wagga Wagga, the region. Narrandera, Leeton, Griffith, Hay and Balranald. The region’s villages Chicken production employs such as Goolgowi, Merriwagga and 350 people in the area, aquaculture Carrathool use aquifers and deep allows the production of Murray bores as their potable supply. cod and cotton has also been grown since 2010. Image: Murrumbidgee River at Wagga Wagga, NSW Carnarvon N.P. r e v i r e R iv e R v i o g N re r r e a v i W R o l g n Augathella a L r e v i R d r a W Chesterton Range N.P. Charleville Mitchell Morven Roma Cheepie Miles River Chinchilla amine Cond Condamine k e e r r ve C i R l M e a nn a h lo Dalby c r a Surat a B e n e o B a Wyandra R Tara i v e r QUEENSLAND Brisbane Toowoomba Moonie Thrushton er National e Riv ooni Park M k Beardmore Reservoir Millmerran e r e ve r i R C ir e e St George W n i Allora b e Bollon N r e Jack Taylor Weir iv R Cunnamulla e n n N lo k a e B Warwick e r C Inglewood a l a l l a g n u Coolmunda Reservoir M N acintyre River Goondiwindi 25 Dirranbandi M Stanthorpe 0 50 Currawinya N.P. -

Cootamundra War Memorial

COOTAMUNDRA WAR MEMORIAL ALBERT PARK – HOVELL STREET COOTAMUNDRA WORLD WAR 1 HONOUR ROLL Compilation by Kevin Casey, Breakfast Point 2012 COOTAMUNDRA WAR MEMORIAL – WORLD WAR 1 A marble obelisk and other memorials have been erected in Albert Park in memory of those citizens of Cootamundra and District who served and died in the defence of Australia during times of conflict. The names of many of those who served in World Wars 1 and 2 are engraved and highlighted in gold on the obelisk. This account has been prepared to provide a background to the men associated with the Cootamundra district who served and died in World War 1. While it is acknowledged that an exhaustive list of local men who served in the war has not been compiled, this account briefly highlights the family and military backgrounds of those who did and who are recorded on the obelisk. Other men not listed on the obelisk but who were associated with the district and who also served and died in the war have been identified in the course of the research. They are also included in this account. No doubt further research will identify more men. Hopefully this account will jog a few memories and inspire further research into the topic. An invitation is extended to interested people to add to the knowledge of those who served Those who served came from a wide range of backgrounds. A number of the men had long family associations with the district and many have family members who are still residents of the district. -

19 Language Revitalisation: Community and School Programs Working Together

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship 19 Language revitalisation: community and school programs working together Diane McNaboe1 and Susan Poetsch2 Abstract Since it was published in 2003 the New South Wales Aboriginal Languages K– 10 Syllabus has led to a substantial increase in the number of school programs operating in the state. It has supported the quality of those programs, and the status and recognition given to Aboriginal languages and cultures in the curriculum. School programs also complement community initiatives to revitalise, strengthen and share Aboriginal languages in New South Wales. As linguistic and cultural knowledge increases among adult community members, school programs provide a channel for them to continue to develop their own skills and knowledge and to pass on this heritage. This paper takes Wiradjuri as an example of language revitalisation, and describes achievements in adult language learning and the process of developing a school program with strong input from community. A brief history of Wiradjuri language revitalisation Wiradjuri is one of the central inland New South Wales (NSW) languages (Wafer & Lissarrague 2008, pp. 215–25). In recent decades various language teams have investigated and analysed archival sources for Wiradjuri and collected information from both written and oral sources (Büchli 2006, pp. 58–60). These teams include Grant and Rudder (2001a, b, c, d; 2005), Hosking and McNicol (1993), McNicol and Hosking (1994) and Donaldson (1984), as well as Christopher Kirkbright, George Fisher and Cheryl Riley, who have been working with Wiradjuri people in and near Sydney. -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

EORA Mapping Aboriginal Sydney 1770–1850 Exhibition Guide

Sponsored by It is customary for some Indigenous communities not to mention names or reproduce images associated with the recently deceased. Members of these communities are respectfully advised that a number of people mentioned in writing or depicted in images in the following pages have passed away. Users are warned that there may be words and descriptions that might be culturally sensitive and not normally used in certain public or community contexts. In some circumstances, terms and annotations of the period in which a text was written may be considered Many treasures from the State Library’s inappropriate today. Indigenous collections are now online for the first time at <www.atmitchell.com>. A note on the text The spelling of Aboriginal words in historical Made possible through a partnership with documents is inconsistent, depending on how they were heard, interpreted and recorded by Europeans. Original spelling has been retained in quoted texts, while names and placenames have been standardised, based on the most common contemporary usage. State Library of New South Wales Macquarie Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone (02) 9273 1414 Facsimile (02) 9273 1255 TTY (02) 9273 1541 Email [email protected] www.sl.nsw.gov.au www.atmitchell.com Exhibition opening hours: 9 am to 5 pm weekdays, 11 am to 5 pm weekends Eora: Mapping Aboriginal Sydney 1770–1850 was presented at the State Library of New South Wales from 5 June to 13 August 2006. Curators: Keith Vincent Smith, Anthony (Ace) Bourke and, in the conceptual stages, by the late Michael -

Narrandera NSW VCA Plant Communities

Office of Environment & Heritage Native Vegetation Map Narrandera ADS-40 Edition 1 NSW VCA Plant Communities NSW VCA ID NSW VCA Name Total Area - Landform pattern / main soil types Characteristic species in each stratum. Note that floristics are relevant to NSW VCA 1:100,000 (8228) this map community over its entire distribution, and may not accurately reflect community make-up (ha) within this mapsheet Grassy Woodlands Western Slopes Grassy Woodlands 276 Yellow Box grassy tall woodland on alluvium or parna loams and 12 Alluvial plain, Low hills / Alluvial soil, Eucalyptus melliodora / Acacia decora - Maireana microphylla / Bothriochloa macra - clays on flats in NSW South-western Slopes Bioregion Brown clay, Brown earth, Calcareous red Austrostipa bigeniculata - Austrodanthonia setacea - Vittadinea cuneata earth Floodplain Transition Woodlands 70 White Cypress Pine woodland on sandy loams in central NSW 2,446 Peneplain, Plain / Red earth, Red-brown Callitris glaucophylla / Acacia deanei subsp. deanei - Dodonaea viscosa sens lat. - wheatbelt earth Maireana enchylaenoides - Geijera parviflora / Einadia nutans subsp. nutans - 455000 456000 457000 458000 459000 460000 461000 462000 463000 464000 465000 466000 467000 468000 469000 470000 471000 472000 473000 474000 475000 476000 477000 478000 479000 480000 481000 482000 483000 484000 485000 486000 487000 488000 489000 490000 491000 492000 493000 494000 495000 496000 497000 498000 499000 500000 Austrostipa scabra subsp. scabra - Austrodanthonia eriantha - Sida corrugata # 74 Yellow Box - River Red Gum tall grassy riverine woodland of NSW 2,814 Flood plain, Meander plain / Alluvial soil, Eucalyptus melliodora - Eucalyptus camaldulensis / Acacia deanei subsp. deanei - South-western Slopes and Riverina Bioregions Black earth, Grey clay Acacia stenophylla / Monachather paradoxus - Elymus scaber var. -

Listing and Sitting Arrangements, Nsw Local Court

LISTING AND SITTING ARRANGEMENTS, NSW LOCAL COURT Listing and sitting arrangements of the NSW Local Court Click on the links below to find the listing and sitting arrangements for each court. CHAMBER DAYS – Please note that Chamber Days have been cancelled from August 2020 to March 2021 to allow for the listing of defended work Albion Park Broken Hill Deniliquin Albury Burwood Downing Centre Armidale Byron Bay Dubbo Assessors - Small Claims Camden Dunedoo Ballina Campbelltown Dungog Bankstown Campbelltown Children's Eden Batemans Bay Casino Fairfield Bathurst Central Finley Bega Cessnock Forbes Bellingen Cobar Forster Belmont Coffs Harbour Gilgandra Bidura Children's Court Commonwealth Matters - Glen Innes (Glebe) (see Surry Hills see Downing Centre Gloucester Children’s Court) Condobolin Gosford Blayney Cooma Goulburn Blacktown Coonabarabran Grafton Boggabilla Coonamble Grenfell Bombala Cootamundra Griffith Bourke Corowa Gulgong Brewarrina Cowra Broadmeadow Children's Gundagai Crookwell Court Circuits Gunnedah 1 LISTING AND SITTING ARRANGEMENTS, NSW LOCAL COURT Hay Manly Nyngan Hillston Mid North Coast Children’s Oberon Court Circuit Holbrook Orange Milton Hornsby Parkes Moama Hunter Children’s Court Parramatta Circuit Moree Parramatta Children’s Court Illawarra Children's Court Moruya Peak Hill (Nowra, Pt. Kembla, Moss Moss Vale Vale and Goulburn) Penrith Mt Druitt Inverell Picton Moulamein Junee Port Kembla Mudgee Katoomba Port Macquarie Mullumbimby Kempsey Queanbeyan Mungindi Kiama Quirindi Murrurundi Kurri Kurri Raymond Terrace Murwillumbah -

MIGRATION to AUSTRALIA in the Mid to Late Nineteenth Expected to Be a Heavy Loser, Were Buried in the Meant That the Men’S Social Chinese, in Particular Their Portant

Step Back In Time MIGRATION TO AUSTRALIA In the mid to late nineteenth expected to be a heavy loser, were buried in the meant that the men’s social Chinese, in particular their portant. century a combination of as the whole of his vegetable denominational sections of lives were pursued largely readiness to donate money to For other men the powerful push and pull garden would be ruined, and the local cemetery. outside a family environment the local hospitals and help in Australian family was factors led to an expected other market After a time the graves in and that sexual relations other fund raising efforts. paramount. Emboldened by unprecedented rise in gardeners along the river to the Chinese cemeteries were involved crossing the racial Alliances and associations an intricate system of inter- Chinese migration to other also suffer. exhumed and the bones and cultural divide. began to change over time. marriage, clan and family parts of Asia, the Americas In the mid 1870s the transported to China for Most social activity in the Many Chinese men, part- allegiances and networks, and Australia. Chinese began cultivating reburial. camps took place in the icularly the storekeepers, many Chinese men in The principal source of tobacco and maize, focusing Exhumations were temples, lodges, gambling were members of one of the Australia went on to create migrants was Guangdong their efforts on the Tumut and elaborate and painstaking houses and opium rooms, Christian churches and miniature dynasties and (Kwangtung) Province in Gundagai areas. undertakings and were although home visits and married, mostly to European become highly respected southern China, in the south The growth of the industry carried out through the hui or entertainments also occ- women, although a number within their local comm- west of the province and areas was rapid. -

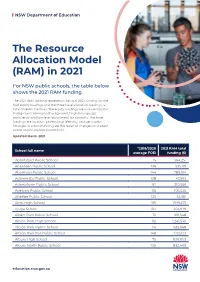

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

Yarnupings Issue 1 March 2018

March 2018 Issue 2 Aboriginal Heritage Office Yarnupings www.aboriginalheritage.org In this Edition: ∗ NSW Aboriginal Knockout in Dubbo 2018 ∗ It’s a Funny World ∗ Is it possible? ∗ Kids page... Nature Page ∗ Crossword & Quizerama ∗ Book Review: A Fortunate Life by A.B Facey ∗ This Months Recipe : Chicken Pot Roast ∗ Strathfield Sites ∗ YarnUp Review: Guest Speaker Tjimpuna ∗ Walk of the Month: West Head Loop Mackerel Beach -West Head Loop Shell Fish -Hooks Page 2 For at least the last thousand years BC (Before Cook) the waters of Warringá (Middle Har- bour), Kay -ye -my (North Harbour), Weé -rong (Sydney Cove) and other Sydney estuaries were the scenes of people using shell fish -hooks to catch a feed. With no known surviving oral tradition for how and who would make the fish -hooks and use them in this area, the historical and archaeological records become more important. What do we know? Shell fish -hooks were observed and reported on by a number of people from the First Fleet. They mention being made and used by local women. “Considering the quickness with which they are finished, the excellence of the work, if it be inspected, is admirable”, Watkin Tench said on witnessing Barangaroo making one on the north shore. First Fleet painting of fish -hook (T. Watling) The manufacturing process involved the use of a strong shell. So far the only archaeological evidence is from the Turbo species. Pointed stone files were used to create the shape and then file down the edges to the recognisable form. Use -wear analysis on files has confirmed that they were used on shell as well as wood, bone and plant material. -

Traditional Wiradjuri Culture

Traditional Wiradjuri Culture By Paul greenwood I would like to acknowledge the Wiradjuir Elders, past and present, and thank those who have assisted with the writing of this book. A basic resource for schools made possible by the assistance of many people. Though the book is intended to provide information on Wiradjuri culture much of the information is generic to Aboriginal culture. Some sections may contain information or pictures from outside the Wiradjuri Nation. Traditional Wiradjuri Culture Wiradjuri Country There were many thousands of people who spoke the Wiradjuri language, making it the largest nation in NSW. The Wiradjuri people occupied a large part of central NSW. The southern border was the Murray River from Albury upstream towards Tumbarumba area. From here the border went north along the edges of the mountains, past Tumut and Gundagai to Lithgow. The territory continued up to Dubbo, then west across the plains to the Willandra creek near Mossgiel. The Booligal swamps are near the western border and down to Hay. From Hay the territory extended across the Riverina plains passing the Jerilderie area to Albury. Wiradjuri lands were known as the land of three rivers; Murrumbidgee (Known by its traditional Wiradjuri name) Gulari (Lachlan) Womboy (Macquarie) Note: The Murrumbidgee is the only river to still be known as its Aboriginal name The exact border is not known and some of the territories overlapped with neighbouring groups. Places like Lake Urana were probably a shared resource as was the Murray River. The territory covers hills in the east, river floodplains, grasslands and mallee country in the west. -

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups For

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups Th is m ap w as e nd orse d by th e Murray Low e r Darling Rive rs Ind ige nous Nations (MLDRIN) for Water Resource Plan Areas - re pre se ntative organisation on 20 August 2018 Groundwater and th e North e rn Basin Aboriginal Nations (NBAN) re pre se ntative organisation on 23 Octobe r 2018 Bidjara Barunggam Gunggari/Kungarri Budjiti Bidjara Guwamu (Kooma) Guwamu (Kooma) Bigambul Jarowair Gunggari/Kungarri Euahlayi Kambuwal Kunja Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Mandandanji Mandandanji Murrawarri Giabel Bigambul Mardigan Githabul Wakka Wakka Murrawarri Githabul Guwamu (Kooma) M Gomeroi/Kamilaroi a r a Kambuwal !(Charleville n o Ro!(ma Mandandanji a GW21 R i «¬ v Barkandji Mutthi Mutthi GW22 e ne R r i i «¬ am ver Barapa Barapa Nari Nari d on Bigambul Ngarabal C BRISBANE Budjiti Ngemba k r e Toowoomba )" e !( Euahlayi Ngiyampaa e v r er i ie Riv C oon Githabul Nyeri Nyeri R M e o r Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Tati Tati n o e i St George r !( v b GW19 i Guwamu (Kooma) Wadi Wadi a e P R «¬ Kambuwal Wailwan N o Wemba Wemba g Kunja e r r e !( Kwiambul Weki Weki r iv Goondiwindi a R Barkandji Kunja e GW18 Maljangapa Wiradjuri W n r on ¬ Bigambul e « Kwiambul l Maraura Yita Yita v a r i B ve Budjiti Maljangapa R i Murrawarri Yorta Yorta a R Euahlayi o n M Murrawarri g a a l rr GW15 c Bigambul Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ngarabal u a int C N «¬!( yre Githabul R Guwamu (Kooma) Ngemba iv er Kambuwal Kambuwal Wailwan N MoreeG am w Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Wiradjuri o yd Barwon River i R ir R Kwiambul !(Bourke iv iv Barkandji e er GW13 C r GW14 Budjiti