Arxiv:1403.6528V1 [Astro-Ph.IM] 25 Mar 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

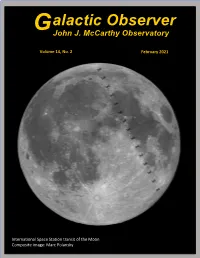

Alactic Observer

alactic Observer G John J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 14, No. 2 February 2021 International Space Station transit of the Moon Composite image: Marc Polansky February Astronomy Calendar and Space Exploration Almanac Bel'kovich (Long 90° E) Hercules (L) and Atlas (R) Posidonius Taurus-Littrow Six-Day-Old Moon mosaic Apollo 17 captured with an antique telescope built by John Benjamin Dancer. Dancer is credited with being the first to photograph the Moon in Tranquility Base England in February 1852 Apollo 11 Apollo 11 and 17 landing sites are visible in the images, as well as Mare Nectaris, one of the older impact basins on Mare Nectaris the Moon Altai Scarp Photos: Bill Cloutier 1 John J. McCarthy Observatory In This Issue Page Out the Window on Your Left ........................................................................3 Valentine Dome ..............................................................................................4 Rocket Trivia ..................................................................................................5 Mars Time (Landing of Perseverance) ...........................................................7 Destination: Jezero Crater ...............................................................................9 Revisiting an Exoplanet Discovery ...............................................................11 Moon Rock in the White House....................................................................13 Solar Beaming Project ..................................................................................14 -

You Every Step of The

with you Every Step of the Way 2016 ANNUAL REPORT $3.5M From the President TOTAL I am pleased to report that your Alumni Association is stronger and more focused than ever! As a result, we have had a greater impact on the Academy experience SUPPORT for our cadets, supporting their academic, athletic and leadership needs — every step of the way — throughout the entire Academy. TO CGA In the following pages, you will read the stories of five cadets whose lives have IN 2016 been touched by your generosity. Their stories are reflective of the impact of your support on all aspects of cadet life. From providing access to the best coaches, equipment and off-campus competitions that unite our cadets as teams and leaders, to investments in educational programs that build confidence and hone the necessary skills of command — it’s clear in the stories and smiles within, that your Alumni Association continues to define the Long Blue Line. This year, we chose to convey our financial success through the voices of these young men and women, but from the Alumni Association board and staff, let me be the voice of gratitude. Because of the generosity of donors to the Alumni Association, in 2016 we surpassed all previous support to the Academy — providing more than $3.5 million in fulfillment of our mission and goals. Nearly 5,000 donors helped us reach this total, 38% of which were alumni donors. Additionally, 35% of the donations received were given in support to the CGA Today! Fund, our area of greatest need. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Astrophysics in 2006 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5760h9v8 Journal Space Science Reviews, 132(1) ISSN 0038-6308 Authors Trimble, V Aschwanden, MJ Hansen, CJ Publication Date 2007-09-01 DOI 10.1007/s11214-007-9224-0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Space Sci Rev (2007) 132: 1–182 DOI 10.1007/s11214-007-9224-0 Astrophysics in 2006 Virginia Trimble · Markus J. Aschwanden · Carl J. Hansen Received: 11 May 2007 / Accepted: 24 May 2007 / Published online: 23 October 2007 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2007 Abstract The fastest pulsar and the slowest nova; the oldest galaxies and the youngest stars; the weirdest life forms and the commonest dwarfs; the highest energy particles and the lowest energy photons. These were some of the extremes of Astrophysics 2006. We attempt also to bring you updates on things of which there is currently only one (habitable planets, the Sun, and the Universe) and others of which there are always many, like meteors and molecules, black holes and binaries. Keywords Cosmology: general · Galaxies: general · ISM: general · Stars: general · Sun: general · Planets and satellites: general · Astrobiology · Star clusters · Binary stars · Clusters of galaxies · Gamma-ray bursts · Milky Way · Earth · Active galaxies · Supernovae 1 Introduction Astrophysics in 2006 modifies a long tradition by moving to a new journal, which you hold in your (real or virtual) hands. The fifteen previous articles in the series are referenced oc- casionally as Ap91 to Ap05 below and appeared in volumes 104–118 of Publications of V. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

Astrophysics in 2006 3

ASTROPHYSICS IN 2006 Virginia Trimble1, Markus J. Aschwanden2, and Carl J. Hansen3 1 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697-4575, Las Cumbres Observatory, Santa Barbara, CA: ([email protected]) 2 Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center, Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory, Organization ADBS, Building 252, 3251 Hanover Street, Palo Alto, CA 94304: ([email protected]) 3 JILA, Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder CO 80309: ([email protected]) Received ... : accepted ... Abstract. The fastest pulsar and the slowest nova; the oldest galaxies and the youngest stars; the weirdest life forms and the commonest dwarfs; the highest energy particles and the lowest energy photons. These were some of the extremes of Astrophysics 2006. We attempt also to bring you updates on things of which there is currently only one (habitable planets, the Sun, and the universe) and others of which there are always many, like meteors and molecules, black holes and binaries. Keywords: cosmology: general, galaxies: general, ISM: general, stars: general, Sun: gen- eral, planets and satellites: general, astrobiology CONTENTS 1. Introduction 6 1.1 Up 6 1.2 Down 9 1.3 Around 10 2. Solar Physics 12 2.1 The solar interior 12 2.1.1 From neutrinos to neutralinos 12 2.1.2 Global helioseismology 12 2.1.3 Local helioseismology 12 2.1.4 Tachocline structure 13 arXiv:0705.1730v1 [astro-ph] 11 May 2007 2.1.5 Dynamo models 14 2.2 Photosphere 15 2.2.1 Solar radius and rotation 15 2.2.2 Distribution of magnetic fields 15 2.2.3 Magnetic flux emergence rate 15 2.2.4 Photospheric motion of magnetic fields 16 2.2.5 Faculae production 16 2.2.6 The photospheric boundary of magnetic fields 17 2.2.7 Flare prediction from photospheric fields 17 c 2008 Springer Science + Business Media. -

Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81z4932 Online items available Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Kate Dundon, Alix Norton, Maureen Carey, Christine Turk, Alex Moore University of California, Santa Cruz 2016 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Lick Observatory Records: UA.036.Ser.07 1 Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Lick Observatory Records: Photographs Creator: Lick Observatory Identifier/Call Number: UA.036.Ser.07 Physical Description: 101.62 Linear Feet127 boxes Date (inclusive): circa 1870-2002 Language of Material: English . https://n2t.net/ark:/38305/f19c6wg4 Conditions Governing Access Collection is open for research. Conditions Governing Use Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. Responsibility for obtaining permissions, and for any use rests exclusively with the user. Preferred Citation Lick Observatory Records: Photographs. UA36 Ser.7. Special Collections and Archives, University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz. Alternative Format Available Images from this collection are available through UCSC Library Digital Collections. Historical note These photographs were produced or collected by Lick observatory staff and faculty, as well as UCSC Library personnel. Many of the early photographs of the major instruments and Observatory buildings were taken by Henry E. Matthews, who served as secretary to the Lick Trust during the planning and construction of the Observatory. -

Spottiswoode-Cusack Co

SO SOUTH ESSEX AVENUE and D. L. & W R. R., ORANGE 329 WASHINGTON STREET AND ERIE R. R . --------ORANGE Spottiswoode-Cusack Co. CRUSHED STONE - - - - TELEPHONE ORANGE 3-0032 COAL TELEPHONE LUMBER TELEPHONE COAL - LUMBER - FUEL OIL KOPPERS COKE ORANGE 3-0032 ORANGE 3-3633 IRVINGTON DIRECTORY—1940 roi BARTH BAUMANN — Hugo (Tina) (Haeberle & Barth) 971 Clinton av — Mario (Lorraine) elk Newark r 46 Adams — Madeline emp Westinghouse r 55 Western pky h 40 Chapman pi Batty James W (Rose M) watchman h 357 21st — Mary A mach opr r 169 Melrose av — Hugo F Jr (Edna V) with Haeberle & Barth 971 Batz Helen J rem to Washington — Mary S wid John V h 20 Paine av Clinton av h (403) 9 Chapman pi — Raymond M rem to Washington — Norman D rem to Newark — Joseph P (Louise H) route slsman h 466 Nye av Baucski Theodore (Stephine) rem to Newark — Philip M (Marie F) metal plater h 40 Lincoln pi — Karl A (Friedal) candy mfr 37 Rich h 33 do Baudistel Arthur J elk PruInsCo r 440 Nye av — William 0 (Agnes C) contr Newark h 169 Melrose av — Katherine T wid William h 118 Laurel av — Charles E r 139 Maple av Baumbusch Albert C (Emma L) jewelrywkr h 161 Caro — Lucy r 109 Hillside ter — Eleanor elk Newark r 60 40th lina av — Milton E W (Elsie F) elk Newark h 46 Olympic ter — Emil (Helen M) macaroniwkr h 139 Maple av — Frank R metal spinner r 37 Adams — Robert H elk Millburn r 106 Florence av — Herbert (Frieda K) musician h 34 Linden av — Julius F (Louise) toolmkr h 37 Adams — William died Oct 20 1938 age 71 — Mary wid August r 34 Linden av Baumer Jacob (Helen E) bottler -

Lunar Impact Basins Revealed by Gravity Recovery and Interior

Lunar impact basins revealed by Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory measurements Gregory Neumann, Maria Zuber, Mark Wieczorek, James Head, David Baker, Sean Solomon, David Smith, Frank Lemoine, Erwan Mazarico, Terence Sabaka, et al. To cite this version: Gregory Neumann, Maria Zuber, Mark Wieczorek, James Head, David Baker, et al.. Lunar im- pact basins revealed by Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory measurements. Science Advances , American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), 2015, 1 (9), pp.e1500852. 10.1126/sci- adv.1500852. hal-02458613 HAL Id: hal-02458613 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02458613 Submitted on 26 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. RESEARCH ARTICLE PLANETARY SCIENCE 2015 © The Authors, some rights reserved; exclusive licensee American Association for the Advancement of Science. Distributed Lunar impact basins revealed by Gravity under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial License 4.0 (CC BY-NC). Recovery and Interior Laboratory measurements 10.1126/sciadv.1500852 Gregory A. Neumann,1* Maria T. Zuber,2 Mark A. Wieczorek,3 James W. Head,4 David M. H. Baker,4 Sean C. Solomon,5,6 David E. Smith,2 Frank G. -

Modeling Polarimetric Radar Scattering from the Lunar Surface: Study on the Effect of Physical Properties of the Regolith Layer Wenzhe Fa, Mark Wieczorek, Essam Heggy

Modeling polarimetric radar scattering from the lunar surface: Study on the effect of physical properties of the regolith layer Wenzhe Fa, Mark Wieczorek, Essam Heggy To cite this version: Wenzhe Fa, Mark Wieczorek, Essam Heggy. Modeling polarimetric radar scattering from the lunar sur- face: Study on the effect of physical properties of the regolith layer. Journal of Geophysical Research. Planets, Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, 116 (E3), pp.E03005. 10.1029/2010JE003649. hal-02458568 HAL Id: hal-02458568 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02458568 Submitted on 26 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 116, E03005, doi:10.1029/2010JE003649, 2011 Modeling polarimetric radar scattering from the lunar surface: Study on the effect of physical properties of the regolith layer Wenzhe Fa,1 Mark A. Wieczorek,1 and Essam Heggy1,2 Received 10 May 2010; revised 21 November 2010; accepted 15 December 2010; published 5 March 2011. [1] A theoretical model for radar scattering from the lunar regolith using the vector radiative transfer theory for random media has been developed in order to aid in the interpretation of Mini‐SAR data from the Chandrayaan‐1 and Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter missions. -

Monday Morning, October 19, 2015 Atom Probe Tomography Focus Topic Complex Device Such As Solar Cells and Batteries Is the Need of the Hour

Monday Morning, October 19, 2015 Atom Probe Tomography Focus Topic complex device such as solar cells and batteries is the need of the hour. Here we report on laser assisted atom probe tomography of energy storage Room: 230A - Session AP+AS+MC+MI+NS-MoM and conversion devices to identify the spatial distribution of the elements comprising the various layers and materials. Recent progress and significant Atom Probe Tomography of Nanomaterials challenges for preparation and study of perovskite solar cells and battery materials using laser assisted atom probe tomography will be discussed. Moderator: Daniel Perea, Pacific Northwest National This opens up new avenues to understand complex mutli-layer systems at Laboratory the atomic scale and provide a nanoscopic view into the intricate workings of energy materials. 8:20am AP+AS+MC+MI+NS-MoM1 Correlative Multi-scale Analysis of Nd-Fe-B Permanent Magnet, Taisuke Sasaki, T. Ohkubo, K. Hono, 10:00am AP+AS+MC+MI+NS-MoM6 Atom Probe Tomography of Pt- National Institute for Materials Science (NIMS), Japan INVITED based Nanoparticles, Katja Eder, P.J. Felfer, J.M. Cairney, The (Nd,Dy)–Fe–B based sintered magnets are currently used for traction University of Sydney, Australia motors and generators of (hybrid) electric vehicles because of their Pt nanoparticles are commonly used as catalysts in fuel cells. There are a lot excellent combination of maximum energy product and coercivity. of factors which influence the activity of a catalyst, including the surface However, there is a strong demand to achieve high coercivity without using structure and geometry [1], d-band vacancy of the metal catalyst [2], the Dy due to its scarce natural resources and high cost. -

Star0 4 Dec121985

1986004609 1 , STAR0 4 DEC121985 _-- NASA Contractor Report 171904 1 _";_ ic33 NASA/ASEE Summer Faculty Fellowship Program Rc3earch Reports _ _'don B. J _.nson Space Cenr.er •_- e T_as A&M U_iversity _, • .... E _T,_,,_ _-_ ," - PAC_/Ty_N{_SA-C_-I7190_)EELLO_SBI_TBE1983 NAS&/ASEE SUMMEB N86-I_078 _ _' i_ REPORTS Final _e_ortsRES_A'_CB P£OGRAM RESEARCH THR0 HC A18/t_F AO1 N86-1_I05 ii _'_ CSCI 051 Uncles _ G3/85 02928 _ Editors : • _ Dr. Walter J. Horn ,. Professor of Aerospace Engineering ._ { < Texas A&M University .,," i College Station, Texas ;_-' [ •% Dr. Michael B. Duke ;. Office of University Affairs ', Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center " Houston, Texas ,_- I ; 1 "! t k # < September 1983 L \ ' ' ,,"r Prepared for .'.2 i ,,_. NASA Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center -._ Houston, Texas 77056 ,c ]986004609-002 . i •"i PREFACE - The 1983 NASA/ASEE Stmner Faculty Fellowship Research Program was conducted _. by Texas A&M University and the Lyudon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC). The lO-week program was operated under the auspices of the American Society for : Engineering Education (ASEE) These programs, conducted by JSC and other "_ NASA Centers, began in 1964. They are sponsored and funded by the Office oi -_ University Affairs, NASA Headquarters, Washington, D.C. The objectives of _ the programs are the followlng: • • : a. To further the professional knowledge of qualified engineering and science faculty members b. To st_nulate an exch_ge of ideas between participants and NASA ¢ c. To enrich and refresh the research and teaching activities of participants' institutions d. -

November 16, 2005 (Download PDF)

Volume 50 – Number 9 Wednesday – November 16, 2005 TechTalk S ERVING T HE M I T C OMMUNITY Solar power has shining moment Sarah H. Wright News Office As the autumn sun set, MIT celebrated the completion of its third and largest solar installation at Hayden Memorial Library on Monday, Nov. 14. President Susan Hockfield seized the moment of natural beauty to affirm the Institute’s commitment to innovations in energy use. Thanks to the MIT Community Solar Power Initiative and to those who installed the 42 solar panels on the library’s roof, much of the sun’s “energy is being cap- PHOTO / DONNA COVENEY tured and converted to electricity to help Cambridge Mayor Michael Sullivan joined power a portion of the essential functions President Susan Hockfield in the ribbon- of this library,” Hockfield said. cutting ceremony for the new installation. The president noted that the installation of the system atop the library represented ect off the ground and for investing in the the successful culmination of a project to Massachusetts innovation economy.” promote sustainable energy on campus The library roof was selected for the and facilitate education and research in solar installation by the Department of solar power as well as to reduce MIT’s Facilities for its southern exposure. The emissions footprint. 12,000-watt system on the library’s roof is Jamie Lewis Keith, senior counsel and comprised of 42 panels, each measuring 2 managing director for MIT Environmen- feet by 5 feet and containing 72 photo vol- tal Programs, noted that Hockfield had taic cells.