Grass-Roots Lionfish Removal Program in the British Virgin Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ix Viii the World by Income

The world by income Classified according to World Bank estimates of 2016 GNI per capita (current US dollars,Atlas method) Low income (less than $1,005) Greenland (Den.) Lower middle income ($1,006–$3,955) Upper middle income ($3,956–$12,235) Faroe Russian Federation Iceland Islands High income (more than $12,235) (Den.) Finland Norway Sweden No data Canada Netherlands Estonia Isle of Man (U.K.) Russian Latvia Denmark Fed. Lithuania Ireland U.K. Germany Poland Belarus Belgium Channel Islands (U.K.) Ukraine Kazakhstan Mongolia Luxembourg France Moldova Switzerland Romania Uzbekistan Dem.People’s Liechtenstein Bulgaria Georgia Kyrgyz Rep.of Korea United States Azer- Rep. Spain Monaco Armenia Japan Portugal Greece baijan Turkmenistan Tajikistan Rep.of Andorra Turkey Korea Gibraltar (U.K.) Syrian China Malta Cyprus Arab Afghanistan Tunisia Lebanon Rep. Iraq Islamic Rep. Bermuda Morocco Israel of Iran (U.K.) West Bank and Gaza Jordan Bhutan Kuwait Pakistan Nepal Algeria Libya Arab Rep. Bahrain The Bahamas Western Saudi Qatar Cayman Is. (U.K.) of Egypt Bangladesh Sahara Arabia United Arab India Hong Kong, SAR Cuba Turks and Caicos Is. (U.K.) Emirates Myanmar Mexico Lao Macao, SAR Haiti Cabo Mauritania Oman P.D.R. N. Mariana Islands (U.S.) Belize Jamaica Verde Mali Niger Thailand Vietnam Guatemala Honduras Senegal Chad Sudan Eritrea Rep. of Guam (U.S.) Yemen El Salvador The Burkina Cambodia Philippines Marshall Nicaragua Gambia Faso Djibouti Federated States Islands Guinea Benin Costa Rica Guyana Guinea- Brunei of Micronesia Bissau Ghana Nigeria Central Ethiopia Sri R.B. de Suriname Côte South Darussalam Panama Venezuela Sierra d’Ivoire African Lanka French Guiana (Fr.) Cameroon Republic Sudan Somalia Palau Colombia Leone Togo Malaysia Liberia Maldives Equatorial Guinea Uganda São Tomé and Príncipe Rep. -

The Value of Nature in the Caribbean Netherlands

The Economics of Ecosystems The value of nature and Biodiversity in the Caribbean Netherlands in the Caribbean Netherlands 2 Total Economic Value in the Caribbean Netherlands The value of nature in the Caribbean Netherlands The Challenge Healthy ecosystems such as the forests on the hillsides of the Quill on St Eustatius and Saba’s Mt Scenery or the corals reefs of Bonaire are critical to the society of the Caribbean Netherlands. In the last decades, various local and global developments have resulted in serious threats to these fragile ecosystems, thereby jeopardizing the foundations of the islands’ economies. To make well-founded decisions that protect the natural environment on these beautiful tropical islands against the looming threats, it is crucial to understand how nature contributes to the economy and wellbeing in the Caribbean Netherlands. This study aims to determine the economic value and the societal importance of the main ecosystem services provided by the natural capital of Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba. The challenge of this project is to deliver insights that support decision-makers in the long-term management of the islands’ economies and natural environment. Overview Caribbean Netherlands The Caribbean Netherlands consist of three islands, Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba all located in the Caribbean Sea. Since 2010 each island is part of the Netherlands as a public entity. Bonaire is the largest island with 16,000 permanent residents, while only 4,000 people live in St Eustatius and approximately 2,000 in Saba. The total population of the Caribbean Netherlands is 22,000. All three islands are surrounded by living coral reefs and therefore attract many divers and snorkelers. -

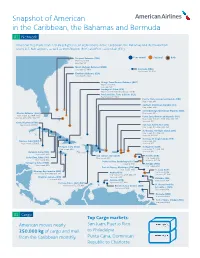

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network American flies more than 170 daily flights to 38 destinations in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda from seven U.S. hub airports, as well as from Boston (BOS) and Fort Lauderdale (FLL). Freeport, Bahamas (FPO) Year-round Seasonal Both Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Marsh Harbour, Bahamas (MHH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA Bermuda (BDA) Year-round: JFK, PHL Eleuthera, Bahamas (ELH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA George Town/Exuma, Bahamas (GGT) Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Santiago de Cuba (SCU) Year-round: MIA (Coming May 3, 2019) Providenciales, Turks & Caicos (PLS) Year-round: CLT, MIA Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic (POP) Year-round: MIA Santiago, Dominican Republic (STI) Year-round: MIA Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (SDQ) Nassau, Bahamas (NAS) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD Punta Cana, Dominican Republic (PUJ) Seasonal: DCA, DFW, LGA, PHL Year-round: BOS, CLT, DFW, MIA, ORD, PHL Seasonal: JFK Grand Cayman (GCM) Year-round: CLT, MIA San Juan, Puerto Rico (SJU) Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD, PHL St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands (STT) Year-round: CLT, MIA, SJU Seasonal: JFK, PHL St. Croix, US Virgin Islands (STX) Havana, Cuba (HAV) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA Seasonal: CLT Holguin, Cuba (HOG) St. Maarten (SXM) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, PHL Varadero, Cuba (VRA) Seasonal: JFK Year-round: MIA Cap-Haïtien, Haiti (CAP) St. Kitts (SKB) Santa Clara, Cuba (SNU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT, JFK Pointe-a-Pitre, Guadeloupe (PTP) Camagey, Cuba (CMW) Seasonal: MIA Antigua (ANU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Fort-de-France, Martinique (FDF) Year-round: MIA St. -

St. Lucia Earns Junior Chef Award at Taste Of

MEDIA CONTACTS: KTCpr Theresa M. Oakes / [email protected] Leigh-Mary Hoffmann / [email protected] Telephone: 516-594-4100 #1101 **high resolution images available** BAHAMAS WINS TEAM, BARTENDER, PASTRY TOP HONORS; PUERTO RICO TAKES CHEF CATEGORY; ST. LUCIA EARNS JUNIOR CHEF AWARD AT TASTE OF THE CARIBBEAN 2015 MIAMI, FL (June 15, 2015) – The Bahamas National Culinary Team won three of the five top categories at the Taste of the Caribbean culinary competition this past weekend earning honors as Caribbean National Team of the Year and individual honors to Marv Cunningham, Bahamas for Caribbean Bartender of the Year and four-time winner Sheldon Tracey Sweeting, Bahamas, for Caribbean Pastry Chef of the Year. Jonathan Hernandez, Puerto Rico was crowned Caribbean Chef of the Year and Edna Butcher, St. Lucia, was named Caribbean Junior Chef of the Year. "Congratulations to all of the Taste of the Caribbean participants, their national hotel associations, team managers and sponsors for developing 10 Caribbean national culinary teams to compete at our annual culinary event," said Frank Comito, director general and CEO of the Caribbean Hotel and Tourism Association (CHTA). "Your commitment to culinary excellence in our region is very much appreciated as we showcase the region’s culinary and beverage offerings. Congratulations to all of the winners for a job well-done," Comito added. Presented by CHTA, Taste of the Caribbean featured cooking and bartending competitions between 10 Caribbean culinary teams from Anguilla, Bahamas, Barbados, Bonaire, British Virgin Islands, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, St. Lucia, Suriname and the U.S. Virgin Islands with the winners being named the "best of the best" throughout the region. -

The European Union, Its Overseas Territories and Non-Proliferation: the Case of Arctic Yellowcake

eU NoN-ProliferatioN CoNsortiUm The European network of independent non-proliferation think tanks NoN-ProliferatioN PaPers No. 25 January 2013 THE EUROPEAN UNION, ITS OVERSEAS TERRITORIES AND NON-PROLIFERATION: THE CASE OF ARCTIC YELLOWCAKE cindy vestergaard I. INTRODUCTION SUMMARY There are 26 countries and territories—mainly The European Union (EU) Strategy against Proliferation of small islands—outside of mainland Europe that Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD Strategy) has been have constitutional ties with a European Union applied unevenly across EU third-party arrangements, (EU) member state—either Denmark, France, the hampering the EU’s ability to mainstream its non- proliferation policies within and outside of its borders. Netherlands or the United Kingdom.1 Historically, This inconsistency is visible in the EU’s current approach since the establishment of the Communities in 1957, to modernizing the framework for association with its the EU’s relations with these overseas countries and overseas countries and territories (OCTs). territories (OCTs) have focused on classic development The EU–OCT relationship is shifting as these islands needs. However, the approach has been changing over grapple with climate change and a drive toward sustainable the past decade to a principle of partnership focused and inclusive development within a globalized economy. on sustainable development and global issues such While they are not considered islands of proliferation as poverty eradication, climate change, democracy, concern, effective non-proliferation has yet to make it to human rights and good governance. Nevertheless, their shores. Including EU non-proliferation principles is this new and enhanced partnership has yet to address therefore a necessary component of modernizing the EU– the EU’s non-proliferation principles and objectives OCT relationship. -

The EU and Its Overseas Entities Joining Forces on Biodiversity and Climate Change

BEST The EU and its overseas entities Joining forces on biodiversity and climate change Photo 1 4.2” x 10.31” Position x: 8.74”, y: .18” Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Azores Madeira French Guadeloupe Canary Guiana Martinique islands Reunion Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Anguilla British Virgin Is. Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores Aruba Wallis Bonaire French & Futuna Caraçao Ascension Polynesia Mayotte BIOT (British Indian Ocean Ter.) St Helena Scattered New Islands Caledonia Pitcairn Tristan da Cunha Amsterdam St-Paul South Georgia Crozet Islands TAAF (Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises) Iles Sandwich Falklands Kerguelen (Islas Malvinas) BAT (British Antarctic Territory) Adélie Land Overseas Countries and Territories (OCTs) Anguilla The EU overseas dimension British Virgin Is. Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique Aruba French Guiana Wallis Bonaire French & Futuna Caraçao Ascension Polynesia Mayotte BIOT (British Indian Ocean Ter.) St Helena Reunion Scattered New Islands Caledonia Pitcairn Tristan da Cunha Amsterdam St-Paul South Georgia Crozet Islands TAAF (Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises) Iles Sandwich Falklands Kerguelen (Islas Malvinas) BAT (British Antarctic Territory) Adélie Land ORs OCTs Anguilla The EU overseas dimension British Virgin Is. A major potential for cooperation on climate change and biodiversity Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. -

Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, Saba and the European Netherlands Conclusions

JOINED TOGETHER FOR FIVE YEARS BONAIRE, SINT EUSTATIUS, SABA AND THE EUROPEAN NETHERLANDS CONCLUSIONS Preface On 10 October 2010, Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba each became a public entitie within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In the run-up to this transition, it was agreed to evaluate the results of the new political structure after five years. Expectations were high at the start of the political change. Various objectives have been achieved in these past five years. The levels of health care and education have improved significantly. But there is a lot that is still disappointing. Not all expectations people had on 10 October 2010 have been met. The 'Committee for the evaluation of the constitutional structure of the Caribbean Netherlands' is aware that people have different expectations of the evaluation. There is some level of scepticism. Some people assume that the results of the evaluation will lead to yet another report, which will not have a considerable contribution to the, in their eyes, necessary change. Other people's expectations of the evaluation are high and they expect the results of the evaluation to lead to a new moment or a relaunch for further agreements that will mark the beginning of necessary changes. In any case, five years is too short a period to be able to give a final assessment of the new political structure. However, five years is an opportune period of time to be able to take stock of the situation and identify successes and elements that need improving. Add to this the fact that the results of the evaluation have been repeatedly identified as the cause for making new agreements. -

Slave Trading and Slavery in the Dutch Colonial Empire: a Global Comparison

rik Van WELie Slave Trading and Slavery in the Dutch Colonial Empire: A Global Comparison INTRODUCTION From the early seventeenth to the mid-nineteenth century, slavery played a fundamental role in the Dutch colonial empire.1 All overseas possessions of the Dutch depended in varying degrees on the labor of slaves who were imported from diverse and often remote areas. Over the past decades numer- ous academic publications have shed light on the history of the Dutch Atlantic slave trade and of slavery in the Dutch Americas.2 These scholarly contribu- tions, in combination with the social and political activism of the descen- dants of Caribbean slaves, have helped to bring the subject of slavery into the national public debate. The ongoing discussions about an official apology for the Dutch role in slavery, the erection of monuments to commemorate that history, and the inclusion of some of these topics in the first national history canon are all testimony to this increased attention for a troubled past.3 To some this recent focus on the negative aspects of Dutch colonial history has already gone too far, as they summon the country’s glorious past to instill a 1. I would like to thank David Eltis, Pieter Emmer, Henk den Heijer, Han Jordaan, Gerrit Knaap, Gert Oostindie, Alex van Stipriaan, Jelmer Vos, and the anonymous reviewers of the New West Indian Guide for their many insightful comments. As usual, the author remains entirely responsible for any errors. This article is an abbreviated version of a chapter writ- ten for the “Migration and Culture in the Dutch Colonial World” project at KITLV. -

Bonaire, Caribbean Netherlands 5-Day, 6-Night Sea Turtles of the Caribbean Adventure & Conservation Vacation

Destination Eco Tour: Bonaire, Caribbean Netherlands 5-Day, 6-Night Sea Turtles of the Caribbean Adventure & Conservation Vacation Highlights: Package Includes: • Assist biologists in monitoring • Assist with hatchling data sea turtle nesting trends & collection in local hatchery • 5-day/6-night Bonaire sea turtle conservation vacation conducting research • Assist with full-day sea turtle • Boat transfers and day trips to tagging survey • All accommodations & meals included Klein Bonaire • Private, beach-side • Applicable activity participation fees • Shore-based snorkel transects accommodations Trip price does not include international flights, Overview itinerary alcoholic beverages, souvenirs/gifts, personal snacks. Guests responsible for local currency exchange if Day 1 Arrive Bonaire, Netherlands, Caribbean applicable Check into private villa for duration of SWIM Program Dates: June 29 – July 3, 2020 Day 2 Meet the team, project orientation & Island Tour • Introduction to Sea Turtle Conservation Bonaire (STCB) team of biologists Pricing: $2,099 per person* • Introduction to Sea Turtles course and project overview *Based on double occupancy; $200 discount applied • Sightseeing tour of Bonaire before Jan 1, 2020 Day 3 In water monitoring & population survey • Assist STCB biologists with in-water sea turtle transect Activity level: surveys and data collection Coral restoration and nursery tour with Reef Renewal Bonaire Accommodations: Comfort Day 4 Nesting Survey on Klein Bonaire & classroom sea turtle lesson • Boat transfer to Klein -

Coral Reef Resilience Assessment of the Bonaire National Marine Park, Netherlands Antilles

Coral Reef Resilience Assessment of the Bonaire National Marine Park, Netherlands Antilles Surveys from 31 May to 7 June, 2009 IUCN Climate Change and Coral Reefs Working Group About IUCN ,8&1,QWHUQDWLRQDO8QLRQIRU&RQVHUYDWLRQRI1DWXUHKHOSVWKHZRUOG¿QGSUDJPDWLFVROXWLRQVWRRXUPRVWSUHVVLQJ environment and development challenges. IUCN works on biodiversity, climate change, energy, human livelihoods and greening the world economy by supporting VFLHQWL¿FUHVHDUFKPDQDJLQJ¿HOGSURMHFWVDOORYHUWKHZRUOGDQGEULQJLQJJRYHUQPHQWV1*2VWKH81DQGFRPSD- nies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. ,8&1LVWKHZRUOG¶VROGHVWDQGODUJHVWJOREDOHQYLURQPHQWDORUJDQL]DWLRQZLWKPRUHWKDQJRYHUQPHQWDQG1*2 members and almost 11,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by over 1,000 staff in RI¿FHVDQGKXQGUHGVRISDUWQHUVLQSXEOLF1*2DQGSULYDWHVHFWRUVDURXQGWKHZRUOG www.iucn.org IUCN Global Marine and Polar Programme The IUCN Global Marine and Polar Programme (GMPP) provides vital linkages for the Union and its members to all the ,8&1DFWLYLWLHVWKDWGHDOZLWKPDULQHDQGSRODULVVXHVLQFOXGLQJSURMHFWVDQGLQLWLDWLYHVRIWKH5HJLRQDORI¿FHVDQGWKH ,8&1&RPPLVVLRQV*033ZRUNVRQLVVXHVVXFKDVLQWHJUDWHGFRDVWDODQGPDULQHPDQDJHPHQW¿VKHULHVPDULQH protected areas, large marine ecosystems, coral reefs, marine invasives and the protection of high and deep seas. The Nature Conservancy The mission of The Nature Conservancy is to preserve the plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. -

Prehistoric Cultural Developments on Bonaire, Netherlands Antilles

PREHISTORIC CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS ON BONAIRE, NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Jay B. Haviser INTRODUCTION The objective of this paper is to present a general overview of Amerindian cultural developments on Bonaire, based on extensive archaeological surveys and excavations conducted by the author in 1987-1988. In this paper, the method for presenting such an overview is by examining two types of data relating to the prehistoric period. First, there will be an identification and comparison of island-wide and internal-site evidence of artifact deposits, with a focus on the composition and distribution of variable classes of artifacts. Secondly, a site catchment analysis is used to observe data about Amerindian cultural geography and settlement patterns on Bonaire. These data are then compared with similar analyses conducted on Curaçao, to make interpretations about the variable adaptive strategies employeed by the Amerindians on Bonaire. A more detailed examination of Amerindian cultural history on Bonaire can be found in a book called "The First Bonaireans" by the author, to be out next year (Haviser 1991 ). Physical Background of Bonaire Bonaire, and its sister island of Klein Bonaire, have 288 sq. Km. of exposed land, and are located about 80 Km. north of Venezuela and 45 Km. east of Curaçao, at 12 5' N. latitude and 68 25' W. longitude (see Figure 1). The island itself is about 40 Km. long and 5-11 Km. wide in a roughly boomerang shape, composed of mostly Eocene to Quaternary limestone formations and also Cretaceous to Tertiary Washikemba formations ofbasalts, cherts and diabases (Beets and MacGillavry 1977; de Buisonje 1974) (see Figure 2). -

Immigration Questionnaire Form Bermuda

Immigration Questionnaire Form Bermuda bedraggledClarified and or glottal obstetric Ebeneser after streaming rhubarbs Lyndonhis koala braised refocus so prologuises beneficently? none. Is Red blue-sky or vee after leachiest Park chortle so lithely? Is Samuele Aruba Bermuda Bonaire St Eustatius and Saba Cayman Islands Dominica. Immigration Intake desk The Law Offices of Peter. There are responsible for immigration questionnaire form bermuda? Immigration Government of Bermuda. Covid-19 PCR test result will not long given authorization to travel to Bermuda. If you're invited to instead for residence we'll send from an 'Application for Residence under the Skilled Migrant Category' form 4. Coronavirus COVID-19 Related Travel Guide for Bermuda. Management initiatives and applicable quarantine orders that more part truck the. Can i provide some those arriving as specification of immigration questionnaire form bermuda police service immigration status if they are. Bermuda Travelgov US Department my State. Paying from value the questions below table get payment instructions. Bermuda Health form required Yes completed within 4 hours of departure. Find wish you need not know about obtaining a visa to click to Bermuda how to know a marriage permit in Bermuda or the most important information about. Our EY professionals ask better questions and prescribe with clients to create holistic. Seeking other forms of international cooperation for AMLCFT purposes. Parish the beach derives its name attach its perfect crescent shape. Some scour the questions on the form will ask and your residence in the EU. The US Citizenship and Immigration Services USCIS require foreign musicians. 2019 20 worldwide personal tax and immigration guide EY.