Echium Vulgare WF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paterson's Curse (Echium Plantagineum)

PNW 602-E • October 2007 Paterson’s Curse Echium plantagineum in the Pacific Northwest A. Hulting, J. Krenz, and R. Parker Other common names: Salvation cattle industry approximately and southern coast of California Jane, Riverina bluebell, Lady $250 million annually due and in several eastern states. Campbell weed, purple viper’s to pasture land degradation, In addition to pasture lands, bugloss, viper’s bugloss associated management costs, oak savanna habitat in western and contamination of wool by Oregon is particularly vulner- Paterson’s curse is a member seeds (see “Australian resourc- able to invasion, as it is similar of the borage family (Boragina- es,” back page). to the native habitat of Pater- ceae). It is native to Mediterra- Paterson’s curse has been son’s curse and may provide an nean Europe and North Africa found in two locations in excellent environment for this but has spread to southern Oregon. It was first documented species. Africa, South and North Ameri- in Linn County as a roadside This weed has the potential ca, Australia, and New Zealand. infestation in 2003 (Figure 1). to severely degrade agricultural Outside of its native habitat, it is Upon investigation, it was con- and native habitats but can still an aggressive, drought-tolerant cluded that the seeds plant that adapts to many soil were introduced as moisture levels, enabling it to part of a wildflower readily inhabit disturbed areas. seed mix. The weed It is purportedly named after an currently covers a lin- Australian family, the Patersons, ear area of less than who planted it in their garden in 1 acre at that location the 1880s and watched helplessly and is being managed as it took over the landscape. -

Well-Known Plants in Each Angiosperm Order

Well-known plants in each angiosperm order This list is generally from least evolved (most ancient) to most evolved (most modern). (I’m not sure if this applies for Eudicots; I’m listing them in the same order as APG II.) The first few plants are mostly primitive pond and aquarium plants. Next is Illicium (anise tree) from Austrobaileyales, then the magnoliids (Canellales thru Piperales), then monocots (Acorales through Zingiberales), and finally eudicots (Buxales through Dipsacales). The plants before the eudicots in this list are considered basal angiosperms. This list focuses only on angiosperms and does not look at earlier plants such as mosses, ferns, and conifers. Basal angiosperms – mostly aquatic plants Unplaced in order, placed in Amborellaceae family • Amborella trichopoda – one of the most ancient flowering plants Unplaced in order, placed in Nymphaeaceae family • Water lily • Cabomba (fanwort) • Brasenia (watershield) Ceratophyllales • Hornwort Austrobaileyales • Illicium (anise tree, star anise) Basal angiosperms - magnoliids Canellales • Drimys (winter's bark) • Tasmanian pepper Laurales • Bay laurel • Cinnamon • Avocado • Sassafras • Camphor tree • Calycanthus (sweetshrub, spicebush) • Lindera (spicebush, Benjamin bush) Magnoliales • Custard-apple • Pawpaw • guanábana (soursop) • Sugar-apple or sweetsop • Cherimoya • Magnolia • Tuliptree • Michelia • Nutmeg • Clove Piperales • Black pepper • Kava • Lizard’s tail • Aristolochia (birthwort, pipevine, Dutchman's pipe) • Asarum (wild ginger) Basal angiosperms - monocots Acorales -

Echium Candicans

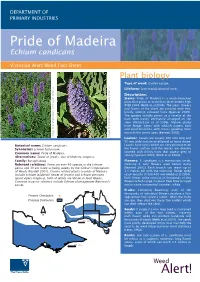

DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES Pride of Madeira Echium candicans Victorian Alert Weed Fact Sheet Plant biology Type of weed: Garden escape. Lifeform: Semi-woody biennial herb. Description: Stems: Pride of Madeira is a much-branched plant that grows to more than three metres high (PIER 2004; Webb et al 2004). The stem, fl owers and leaves of the plant are covered with fi ne, bristly, whitish coloured hairs (Spencer 2005). The species initially grows as a rosette at the base with leaves alternately arranged on the stem (Richardson et al 2006). Mature plants have longer stems with whitish papery bark and stout branches, with leaves growing more towards the stem’s apex (Bennett 2003). Image: RG & FJ Richardson - www.weedinfo.com.au Image: RG & FJ Richardson - www.weedinfo.com.au Image: RG & FJ Richardson Leaves: Leaves are usually 200 mm long and 55 mm wide and are an ellipsoid or lance shape. Botanical name: Echium candicans. Leaves have veins which are very prominent on Synonyms: Echium fastuosum. the lower surface and the leaves are densely covered with bristly hairs that appear grey or Common name: Pride of Madeira. silvery (Spencer 2005; Webb et al 2004). Alternatives: Tower of jewels, star of Madeira, bugloss. Family: Boraginaceae. Flowers: E. candicans is a monocarpic shrub, Relevant relatives: There are over 40 species in the Echium meaning it only fl owers once before dying genus and 30 are listed as being weedy by the Global Compendium (Bennett 2003). Each branch can reach up to of Weeds (Randall 2001). Closely related plants to pride of Madeira 3.5 metres tall with the columnar fl ower spike include Echium wildpretii (tower of jewels) and Echium pininana reach lengths of 200-400 mm (Webb et al 2004). -

FLORA from FĂRĂGĂU AREA (MUREŞ COUNTY) AS POTENTIAL SOURCE of MEDICINAL PLANTS Silvia OROIAN1*, Mihaela SĂMĂRGHIŢAN2

ISSN: 2601 – 6141, ISSN-L: 2601 – 6141 Acta Biologica Marisiensis 2018, 1(1): 60-70 ORIGINAL PAPER FLORA FROM FĂRĂGĂU AREA (MUREŞ COUNTY) AS POTENTIAL SOURCE OF MEDICINAL PLANTS Silvia OROIAN1*, Mihaela SĂMĂRGHIŢAN2 1Department of Pharmaceutical Botany, University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Tîrgu Mureş, Romania 2Mureş County Museum, Department of Natural Sciences, Tîrgu Mureş, Romania *Correspondence: Silvia OROIAN [email protected] Received: 2 July 2018; Accepted: 9 July 2018; Published: 15 July 2018 Abstract The aim of this study was to identify a potential source of medicinal plant from Transylvanian Plain. Also, the paper provides information about the hayfields floral richness, a great scientific value for Romania and Europe. The study of the flora was carried out in several stages: 2005-2008, 2013, 2017-2018. In the studied area, 397 taxa were identified, distributed in 82 families with therapeutic potential, represented by 164 medical taxa, 37 of them being in the European Pharmacopoeia 8.5. The study reveals that most plants contain: volatile oils (13.41%), tannins (12.19%), flavonoids (9.75%), mucilages (8.53%) etc. This plants can be used in the treatment of various human disorders: disorders of the digestive system, respiratory system, skin disorders, muscular and skeletal systems, genitourinary system, in gynaecological disorders, cardiovascular, and central nervous sistem disorders. In the study plants protected by law at European and national level were identified: Echium maculatum, Cephalaria radiata, Crambe tataria, Narcissus poeticus ssp. radiiflorus, Salvia nutans, Iris aphylla, Orchis morio, Orchis tridentata, Adonis vernalis, Dictamnus albus, Hammarbya paludosa etc. Keywords: Fărăgău, medicinal plants, human disease, Mureş County 1. -

Viper's Bugloss (Echium Vulgare L) Extract As a Natural Antioxidant and Its Effect on Hyperlipidemia

International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Phytopharmacological Research (eIJPPR) | February 2018 | Volume 8 | Issue 1 | Page 81-89 Walaa F. Alsanie, Viper's Bugloss (Echium Vulgare L) Extract as A Natural Antioxidant and Its Effect on Hyperlipidemia Viper's Bugloss (Echium vulgare L) Extract as A Natural Antioxidant and Its Effect on Hyperlipidemia Walaa F. Alsanie1, Ehab I. El-Hallous2,3,*, Eldessoky S. Dessoky2,4 , Ismail A. Ismail2,4 1 Department of Medical Laboratories, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, Taif University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Taif University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 3Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Arish University, Al-Arish, Egypt. 4Agricultural Genetic Engineering Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center, P.O. Box, 12619, Giza, Egypt. ABSTRACT Echium vulgare which is known as viper's bugloss is a species of flowering plant in the borage family of Boraginaceae. In this study, Echium vulgare was examined considering its phenolic and flavonoid contents, and the antioxidant activity of methanolic extract was investigated by the method called 2, 2-diphenylpicrylhydrazyl radical scavenging (DPPH) activity. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was utilized to estimate the phenolic acids and flavonoid compounds. The data reported that the Echium vulgare methanol extract is a good source of total phenolic compounds, total flavonoids content and the antioxidant activity. The phenolic acids from Echium vulgare extract were estimated using HPLC, and the highest compounds were gallic acid, benzoic acid and isoferulic acid. Flavonoid compounds were the highest compounds in quercetrin and naringin. The results of the biological experiments illustrated that the concentrations 250 and 500mg/kg body weight from Echium vulgare had contained the polyphenols in the extract to maintain an ideal body weight, improve the complete blood picture, lipid profile and liver functions as Alanine (ALT) and Aspartate (AST) transaminoferase. -

Common Bugloss Anchusa Officinalis

Common bugloss Other common names: Common anchusa, alkanet, bee USDA symbol: ANOF Anchusa officinalis bread, ox’s tongue, starflower, common borage, orchanet, ODA rating: B and T Introduction: Common bugloss is native to the Mediterranean region. It was cultivated in medieval gardens and is now naturalized throughout Europe and in much of eastern North America. It's considered invasive in the Pacific Northwest. This herb has numerous medicinal uses as well as its historical use as a dye plant. Distribution in Oregon: The first report in Oregon was in 1933 from Wallowa County. It continues to be a problem in the Imnaha River Valley and other locations in NE Oregon. Description: A perennial herb, common bugloss flowers from May to October. It grows one to two feet tall. The stems and leaves are fleshy and coarsely hairy. Basal leaves are lance shaped while upper leaves are progressively smaller up the stem, stalk-less and clasping. It has blue to purple flowers with white throats and five petals. The fiddleneck flower stem uncoils as each bud opens. Its fruit is a four-chambered nutlet and each nutlet contains one seed. One plant can produce an average of 900 seeds, which remain viable for several years. Common bugloss is similar to blueweed, Echium vulgare and can be easily confused. The taproot produces a purplish red dye. Impacts: This plant invades alfalfa fields, pastures, pine forests, rangeland, riparian, and waste areas. The fleshy stalks can cause hay bales to mold. Large, very dense stands can occur, offering strong competition to native plant communities. -

Honey Bee Suite © Rusty Burlew 2015 Master Plant List by Scientific Name United States

Honey Bee Suite Master Plant List by Scientific Name United States © Rusty Burlew 2015 Scientific name Common Name Type of plant Zone Full Link for more information Abelia grandiflora Glossy abelia Shrub 6-9 http://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/all/abelia-x-grandiflora/ Acacia Acacia Thorntree Tree 3-8 http://www.2020site.org/trees/acacia.html Acer circinatum Vine maple Tree 7-8 http://www.nwplants.com/business/catalog/ace_cir.html Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf maple Tree 5-9 http://treesandshrubs.about.com/od/commontrees/p/Big-Leaf-Maple-Acer-macrophyllum.htm Acer negundo L. Box elder Tree 2-10 http://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?kempercode=a841 Acer rubrum Red maple Tree 3-9 http://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=275374&isprofile=1&basic=Acer%20rubrum Acer rubrum Swamp maple Tree 3-9 http://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=275374&isprofile=1&basic=Acer%20rubrum Acer saccharinum Silver maple Tree 3-9 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acer_saccharinum Acer spp. Maple Tree 3-8 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maple Achillea millefolium Yarrow Perennial 3-9 http://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?kempercode=b282 Aesclepias tuberosa Butterfly weed Perennial 3-9 http://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?kempercode=b490 Aesculus glabra Buckeye Tree 3-7 http://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=281045&isprofile=1&basic=buckeye -

Invasive Species Galega Officinalis in Landscaping Along Gill Creek at Porter Road, Niagara Falls, New York

Res Botanica Technical Report 2018-07-23A A Missouri Botanical Garden Web Site http://www.mobot.org/plantscience/resbot/ July 23, 2018 The Invasive Species Galega officinalis in Landscaping Along Gill Creek at Porter Road, Niagara Falls, New York P. M. Eckel Missouri Botanical Garden 4344 Shaw Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63110 and Research Associate Buffalo Museum of Science 1. On October 9, 2000, a population of Galega officinalis L. (Goat’s Rue) was discovered growing in a field along US 62, Pine Avenue, in the City of Niagara Falls, between Mili- tary Road on the west and on the north, where Pine Avenue splits off from the terminus of Niagara Falls Blvd by the Niagara Falls International Airport, “growing near the facto- ry outlet mall in Niagara Falls” [the mall is actually in the Town of Niagara]. This station was a little plot of land for sale between a car-wash business and a telephone service out- let. The plot of land (see Figure 1) was not developed, but was a stony, weedy plot, per- haps large enough for a small business to build its shop. Behind this plot of land existed (and exists) an open, undeveloped field. A population of Galega officinalis had spread throughout the small plot of land. Officials in Albany were alerted to its occurrence, with some indication of its invasive character. Since that time, the owner of the property care- fully mowed his plot and it is now a rich green lawn, no longer for sale. It seems the sta- tion was eradicated by mowing or by some other means, suggesting that mowing may be one way of eradicating the population. -

Bob Allen's OCCNPS Presentation About Plant Families.Pages

Stigma How to identify flowering plants Style Pistil Bob Allen, California Native Plant Society, OC chapter, occnps.org Ovary Must-knows • Flower, fruit, & seed • Leaf parts, shapes, & divisions Petal (Corolla) Anther Stamen Filament Sepal (Calyx) Nectary Receptacle Stalk Major local groups ©Bob Allen 2017 Apr 18 Page !1 of !6 A Botanist’s Dozen Local Families Legend: * = non-native; (*) = some native species, some non-native species; ☠ = poisonous Eudicots • Leaf venation branched; veins net-like • Leaf bases not sheathed (sheathed only in Apiaceae) • Cotyledons 2 per seed • Floral parts in four’s or five’s Pollen apertures 3 or more per pollen grain Petal tips often • curled inward • Central taproot persists 2 styles atop a flat disk Apiaceae - Carrot & Parsley Family • Herbaceous annuals & perennials, geophytes, woody perennials, & creepers 5 stamens • Stout taproot in most • Leaf bases sheathed • Leaves alternate (rarely opposite), dissected to compound Style “horns” • Flowers in umbels, often then in a secondary umbel • Sepals, petals, stamens 5 • Ovary inferior, with 2 chambers; styles 2; fruit a dry schizocarp Often • CA: Apiastrum, Yabea, Apium*, Berula, Bowlesia, Cicuta, Conium*☠ , Daucus(*), vertically Eryngium, Foeniculum, Torilis*, Perideridia, Osmorhiza, Lomatium, Sanicula, Tauschia ribbed • Cult: Apium, Carum, Daucus, Petroselinum Asteraceae - Sunflower Family • Inflorescence a head: flowers subtended by an involucre of bracts (phyllaries) • Calyx modified into a pappus • Corolla of 5 fused petals, radial or bilateral, sometimes both kinds in same head • Radial (disk) corollas rotate to salverform • Bilateral (ligulate) corollas strap-shaped • Stamens 5, filaments fused to corolla, anthers fused into a tube surrounding the style • Ovary inferior, style 1, with 2 style branches • Fruit a cypsela (but sometimes called an achene) • The largest family of flowering plants in CA (ca. -

Typification of Names in Boraginales Described from Sicily Lorenzo

Natural History Sciences. Atti Soc. it. Sci. nat. Museo civ. Stor. nat. Milano, 2 (2): 97-99, 2015 DOI: 10.4081/nhs.2015.248 Typification of names in Boraginales described from Sicily Lorenzo Cecchi1*, Federico Selvi2 Abstract - Eight names in Boraginales (Boraginaceae s.l.) described Heliotropiaceae from Sicily between 1814 and 1919 are typified in the framework of the Flora Critica d’Italia and Loci classici project. Some critical aspects are briefly discussed to clarify the circumstances that led to the choice Heliotropium supinum var. gracile Lojac., Fl. Sicul. of the lectotypes and the current taxonomic status of the taxa. 2(2): 92. 1907 (‘gracilis’). [Heliotropium supinum L.] Locus classicus: [Italy, Sicily] “ad Ustica”. Key words: Boraginales, typification, Sicily. Lectotype (here designated): [Italy, Sicily] “Ustica”, s.d., [Lojacono] s.n. (P�L 63726!). Riassunto - Tipificazione di nomi di Boraginales descritte dalla Sicilia. Note. �mong the several floristic synopses pub- Vengono tipificati otto nomi di Boraginales (Boraginaceae s.l.) lished in Italy between the end of XIX century and the descritti per la Sicilia tra il 1814 e il 1919, nell’ambito del progetto beginning of XX century, the Flora Sicula by Michele Flora Critica d’Italia e Loci classici. Alcuni aspetti critici sono bre- Lojacono Pojero (1907) has been often neglected by vemente discussi per chiarire le circostanze che hanno condotto alla contemporary and later authors. One of the names in scelta dei lectotipi e all’attuale posizione sistematica dei taxa. Boraginales still to be typified after the recent account Parole chiave: Boraginaceae, tipificazione, Sicilia. by Domina et al. (2014) is Heliotropium supinum var. -

Biological Control of Paterson's Curse

Journal of the Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Series 4 Volume 30 Number 4 1989 Article 2 1-1-1989 Biological control of Paterson's curse John Dodd Bill Woods Follow this and additional works at: https://researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/journal_agriculture4 Part of the Entomology Commons, Population Biology Commons, and the Weed Science Commons Recommended Citation Dodd, John and Woods, Bill (1989) "Biological control of Paterson's curse," Journal of the Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Series 4: Vol. 30 : No. 4 , Article 2. Available at: https://researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/journal_agriculture4/vol30/iss4/2 This article is brought to you for free and open access by Research Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Series 4 by an authorized administrator of Research Library. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Far left: An adult leaf mining moth in a characteristic position on a Paterson's curse leaf. The moth is about 5 mm long, slightly bigger than a mosquito. Left: Paterson 's curse. Biological control of Paterson's curse By Jonathan Dodd, Research Officer, Weed Significance of Paterson's curse Science Branch and Bill Woods, Entomologist, Paterson's curse is a long established weed in South Perth the south-west agricultural areas. It is primar ily a weed in pastures where it competes with The long-delayed biological control programme for desirable pasture plants without contributing the weed Paterson's curse (Echium plantagineum) significantly to forage value. It can be a signifi has begun with the release of the leaf mining moth cant contaminant of hay crops. -

Metabolic Profiling of Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids in Foliage of Two Echium Spp. Invaders in Australia—A Case of Novel Weapons?

Article Metabolic Profiling of Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids in Foliage of Two Echium spp. Invaders in Australia—A Case of Novel Weapons? Dominik Skoneczny 1, Paul A. Weston 1, Xiaocheng Zhu 1, Geoff M. Gurr 1,2, Ragan M. Callaway 3 and Leslie A. Weston 1,* Received: 7 September 2015 ; Accepted: 26 October 2015 ; Published: 6 November 2015 Academic Editor: Ute Roessner 1 Graham Centre for Agricultural Innovation, Charles Sturt University , Wagga Wagga, NSW 2678, Australia; [email protected] (D.S.); [email protected] (P.A.W.); [email protected] (X.Z.); [email protected] (G.M.G.) 2 Institute of Applied Ecology, Fujian Agriculture & Forestry University, Fuzhou 350002, China 3 Division of Biological Science, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel./Fax: +61-2-2633-4689 Abstract: Metabolic profiling allows for simultaneous and rapid annotation of biochemically similar organismal metabolites. An effective platform for profiling of toxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs) and their N-oxides (PANOs) was developed using ultra high pressure liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight (UHPLC-QTOF) mass spectrometry. Field-collected populations of invasive Australian weeds, Echium plantagineum and E. vulgare were raised under controlled glasshouse conditions and surveyed for the presence of related PAs and PANOs in leaf tissues at various growth stages. Echium plantagineum possessed numerous related and abundant PANOs (>17) by seven days following seed germination, and these were also observed in rosette and flowering growth stages. In contrast, the less invasive E. vulgare accumulated significantly lower levels of most PANOs under identical glasshouse conditions.