Shooting for Lithuania: Migration, National Identity and Men's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sporto Mokslas Sport Science

SPORTO 2008 SPORT 2(52) MOKSLAS VILNIUS SCIENCE LIETUVOS SPORTO MOKSLO TARYBOS LIETUVOS OLIMPINĖS AKADEMIJOS LIETUVOS KŪNO KULTŪROS AKADEMIJOS VILNIAUS PEDAGOGINIO UNIVERSITETO Ž U R N A L A S JOURNAL OF LITHUANIAN SPORTS SCIENCE COUNCIL, LITHUANIAN OLYMPIC ACADEMY, LITHUANIAN ACADEMY OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION AND VILNIUS PEDAGOGICAL UNIVERSITY LEIDŽIAMAS nuo 1995 m.; nuo 1996 m. – prestižinis žurnalas ISSN 1392-1401 Žurnalas įtrauktas į: INDEX COPERNICUS duomenų bazę Indexed in INDEX COPERNICUS Vokietijos federalinio sporto mokslo instituto Included into German Federal Institute for Sport Science literatūros duomenų banką SPOLIT Literature data bank SPOLIT REDAKTORIŲ TARYBA TURINYS Prof. habil. dr. Algirdas BAUBINAS (VU) Prof. habil. dr. Alina GAILIŪNIENĖ (LKKA) ĮVADAS // INTRODUCTION.................................................................2 Prof. dr. Jochen HINSCHING (Greisvaldo u-tas, Vokietija) A. Poviliūnas. Sportas ir politika: teorija ir praktika Prof. habil. dr. Algimantas IRNIUS (VU) šių laikų olimpinėje istorijoje ......................................................................2 Prof. habil. dr. Jonas JANKAUSKAS (VU) Prof. habil. dr. Janas JAŠČANINAS (Ščecino universitetas, sporto MOKSLO PSICHOLOGIJA // Lenkija) sports PSYCHOLOGY ............................................................................6 Prof. habil. dr. Julius kalibatas (Sveikatos apsaugos minis- R. Malinauskas, Š. Šniras. Psichologinio rengimo programos poveikis terijos Higienos institutas) didelio meistriškumo krepšininkų psichologiniams įgūdžiams -

Soft Power Played on the Hardwood: United States Diplomacy Through Basketball

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2015 Soft oP wer Played on the Hardwood: United States Diplomacy through Basketball Joseph Bertka Eyen Pitzer College Recommended Citation Eyen, Joseph Bertka, "Soft oP wer Played on the Hardwood: United States Diplomacy through Basketball" (2015). Pitzer Senior Theses. 86. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/86 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOFT POWER PLAYED ON THE HARDWOOD United States Diplomacy through Basketball by Joseph B. Eyen Dr. Nigel Boyle, Political Studies, Pitzer College Dr. Geoffrey Herrera, Political Studies, Pitzer College A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Political Studies Pitzer College Claremont, California 4 May 2015 2 ABSTRACT This thesis demonstrates the importance of basketball as a form of soft power and a diplomatic asset to better achieve American foreign policy, which is defined and referred to as basketball diplomacy. Basketball diplomacy is also a lens to observe the evolution of American power from 1893 through present day. Basketball connects and permeates foreign cultures and effectively disseminates American influence unlike any other form of soft power, which is most powerfully illustrated by the United States’ basketball relationship with China. American basketball diplomacy will become stronger and connect with more countries with greater influence, and exist without relevant competition, until the likely rise of China in the indefinite future. -

Organizing Committee World Rowing Masters Regatta 2008 Lithuania

Dear guests of World Masters Regatta, dear participants, Let our beautiful sports traditions be continued in Trakai, and the victories that glorified the name of Lithuania, and achievements „ ... Sport has to be noble, pure and bright. It has to subli- For the first time, in 2002 World Junior Championship I consider the news that Lithuania is allowed to organize that helped to break the iron curtain encourage the Lithuanian mate man, evolve together with society values ...“ was organized in Trakai with great success. The World Masters Regatta 2008 as a gratifying and honourable masters to achieve new victories today and in the future, joint (E. Curtius). expressed trust of FISA to organize World Rowing commitment. I believe that it is not an accidental confidence our nationals throughout the world, inspire confidence in their Masters Regatta 2008 is an exclusive appreciation but a significant obligation expressed towards and underta- abilities at the highest level international contests. World Rowing Masters Regatta 2008 in Lithuania of our country and rowing professionalism. ken by our sportsmen, organizers and the whole Lithuanian proves this saying. It is not without reason that all I believe that it is a great event for our country, sports community, the citizens authorities of the City of Trakai. Our sports community is sincerely looking forward to the world rowers’ great interest in this sport, which rowing masters, respect to masters and stimulus welcoming you – the guests of Lithuania. I hope that after requires immense stamina, strength and persistence, to young people. I hope that this beautiful event in addition to history and tou- the completion of the World Masters Regatta, the masters unifies them on water tracks. -

Ponuda Za LIVE 30.12.2017

powered by BetO2 kickoff_time event_id sport competition_name home_name away_name 2017-12-30 09:00:00 1050635 BASKETBALL South Korea KBL KCC Egis Seoul Thunders 2017-12-30 09:00:00 1050636 BASKETBALL South Korea WKBL Woori Bank Hansae Women Bucheon Keb Hanabank Women 2017-12-30 09:30:00 1050637 BASKETBALL Australia WNBL Women Melbourne Boomers Women Dandenong Women 2017-12-30 11:00:00 1050638 BASKETBALL Turkey Super Ligi Sakarya Pinar Karsiyaka 2017-12-30 11:30:00 1050733 BASKETBALL Turkey TBL Bahcesehir Koleji Socar Petkimspor 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050639 BASKETBALL China WCBA Bayi Women Xinjiang Women 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050640 BASKETBALL China WCBA Guangdong Women Jiangsu Women 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050641 BASKETBALL China WCBA Liaoning Women Beijing Women 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050642 BASKETBALL China WCBA Shenyang Women Zhejiang Women 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050643 BASKETBALL China WCBA Shandong Women Shanxi Xing Rui Women 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050644 BASKETBALL China WCBA Shanghai Women Shaanxi Tianze Women 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050866 BASKETBALL China WCBA Sichuan Women Heilongjiang Women 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050758 BASKETBALL Turkey TBL Bakirkoy Yalova Belediye 2017-12-30 12:35:00 1050647 BASKETBALL China CBA Sichuan Guangzhou 2017-12-30 12:35:00 1050648 BASKETBALL China CBA Qingdao Beikong 2017-12-30 12:35:00 1050649 BASKETBALL China CBA Zhejiang Chouzhou Bank Jiangsu Dragons 2017-12-30 13:00:00 1050645 BASKETBALL China CBA Xinjiang Shenzhen 2017-12-30 13:15:00 1050650 BASKETBALL Turkey Super Ligi Usak Eskisehir Basket 2017-12-30 14:00:00 -

Eagle Men's Basketball 2018-19

EAGLE MEN’S BASKETBALL 2018-19 Syracuse University University of Wisconsin-Green Bay University of Washington “ORANGE” “PHOENIX” “HUSKIES” Location: Syracuse, New York Location: Green Bay, Wisconsin Location: Seattle, Washington Enrollment: 14,847 Enrollment: 6,815 Enrollment: 46,165 Affiliation: NCAA Division I Affiliation: NCAA Division I Affiliation: NCAA Division I Conference: Atlantic Coast Conference Conference: Horizon League Conference: Pac-12 Conference Arena: Carrier Dome (35,446) Arena: Resch Center (9,877) Arena: Alaska Airlines Arena (10,000) Head Coach: Jim Boeheim Head Coach: Linc Darner Head Coach: Mike Hopkins SU Record: 926-371 / 42 Seasons UWGB Record: 54-47 / Three Seasons UW Record: 21-13 / One Season Career Record: Same Career Record: 347-164 / 16 Seasons Career Record: 21-13 / One Season 2017-18: 23-14 / 8-10 (t-10th) 2017-18: 13-20 / 7-11 (7th) 2017-18: 21-13 / 10-8 (t-6th) Top Returning Scorers: Top Returning Scorers: Top Returning Scorers: Tyus Battle (G, 6-6, Jr., 19.2ppg, 2.9rpg) Sandy Cohen III (G, 6-6, R-Sr., 16.1ppg, 5.7rpg) Jaylen Nowell (G, 6-4, So., 16.0ppg, 4.0rpg) Oshae Brissett (F, 6-8, So., 14.9ppg, 8.8rpg Kameron Hankerson (G, 6-5, Jr., 10.7ppg, 3.1rpg) Noah Dickerson (F, 6-8, Sr., 15.5ppg, 8.4rpg) Frank Howard (G, 6-5, Sr., 14.4ppg, 4.7apg) PJ Pipes (G, 6-2, So., 7.2ppg, 2.3rpg) David Crisp (G, 6-0, Sr., 11.6ppg, 3.1apg) SID: Pete Moore SID: Joey Daniels SID: Ashley Walker 315.443.2608 920.465.2498 206.240.3899 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Website: www.cuse.com Website: www.greenbayphoenix.com -

Youth Player Development Programmes

LITHUANIAN BASKETBALL FEDERATION 2nd Seminar for National Federations FIBA Europe, Munich, 2009 Youth Player Development Programmes LBF Secretary general Mindaugas Balciunas MAIN REASONS OF THE BASKETBALL SUCCESS IN LITHUANIA General popularity of the Well organized training process basketball sport (Well educated coaches, good infrastructure, good local (Historical victories, exceptional attention of the Government, competitional system) huge media cover, Nr 1 kind of sport in Lithuania) LITHUANIAN BASKETBALL SUCCESS Productive general management system Very good selection (All the segments involved in the management, small country (Most talanted kids coming to the basketball, wide net of is advantage in the development, system based on basketball schools, clubs and etc., many local competitions) autonomical associations) LITHUANIAN BASKETBALL FEDERATION GENERAL MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE All members of LBF: basketball clubs, General Conference schools,schools, associations,associations, townstowns federations etc. Composed of representatives of 4 Men’s, 2 Executive Board Women’s leagues, Coaches and Referees associations, Youth and Veterans leagues Elected by the General Conference for four LBF President year period Approved by the Executive Board under LBF Secretary General recommendation of the President LBF Administration Employed by the President and Secretary General LITHUANIAN BASKETBALL FEDERATION MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE LBF President Secretary general Office Commerci Youth NT Project’s Media Accounting administrato al director managers -

REPORT on the Free Movement of Workers in Lithuania in 2012-2013

REPORT on the Free Movement of Workers in Lithuania in 2012-2013 Rapporteur: Prof. dr. Lyra Jakuleviciene Mykolas Romeris University July 2013 Contents Abbreviations Introduction Chapter I The Worker: Entry, residence, departure and remedies Chapter II Members of the family Chapter III Access to employment Chapter IV Equality of treatment on the basis of nationality Chapter V Other obstacles to free movement of workers Chapter VI Specific issues Chapter VII Application of transitional measures Chapter VIII Miscellaneous LITHUANIA Abbreviations AL Aliens’ Law Certificate document confirming the right of temporary residence for EU national in Lithuania EC European Commission CJEU Court of Justice of the European Union EU Residence Card document confirming the right of temporary or permanent residence in the Republic of Lithuania of a TCN family member of EU national or other person who is entitled to free movement of persons under EU law EU Residence Certificate document issued to EU national or his/her family member EEA European Economic Area EU European Union EU Residence Permit document issued to a third country national, who is EU national’s family member EU Permanent Residence Permit document confirming permanent residence right and issued to a third country national, who is EU national’s family member FIFA Federation of International Football Associations LBF Lithuanian Basketball Federation LFF Lithuanian Football Federation LVF Lithuanian Volleyball Federation MOI Ministry of Interior MES Ministry of Education and Science MS(s) Member State (s) MSSL Ministry of Social Security and Labour SODRA Social Insurance Fund TCN(s) Third Country National (s) UK the United Kingdom 3 LITHUANIA Introduction Among the most important developments that could be observed for the year 2012 and first half of 2013 the legislative reform could be mentioned by virtue of adoption of substantive package of amendments to the Aliens’ Law on 30 June 2012, which entered into force on 1 January 2013. -

The Power of Basketball in Lithuania Kazickas Family Foundation

THE POWER OF BASKETBALL IN LITHUANIA KAZICKAS FAMILY FOUNDATION U.N. SDG GOAL # 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.1 GRANT ELIGIBILITY PERIOD: March 2006 – March 2015 AMOUNT: $5,000 NBA Cares and KFF event 2006, Vilnius, LT Photo C.Bruning PROGRAM SUMMARY: GRANT IMPACT: This grant was necessary to refurbish the In 2015, CAF America made a grant of basketball court built by the Kazickas Family $5,000 to the Kazickas Family Foundation. Foundation in partnership with NBA Cares in The grant’s primary objective was to fund the Vilnius, Lithuania in 2006. The refurbishment refurbishment of a basketball court in Vilnius, of the court includes the replacement of Lithuania built in 2006 through a partnership basketball stands and hoops, the restoration between the Kazickas Family Foundation of the fence surrounding the court, and and NBA Cares. The grant enabled the a complete refinishing and repainting of installation of a new polyurethane surface, the court’s surface. KFF’s main focus in as well as new equipment fixtures and refurbishing the court is the continued fencing. As of May 2015 the refurbishment is promotion of fitness and overall physical underway, in time for the scheduled summer and mental health for Lithuanian youth launch of The Power of Basketball initiative. GRANTEE OVERVIEW: through The Power of Basketball initiative, Once completed, the court will be open to The Kazickas family’s philanthropy is launched in 2015. The Power of Basketball the students of the adjacent public school motivated by a wish to create a better world is a social responsibility program created and the public at large. -

Lietuvos Kūno Kultūros Akademija

LIETUVOS KŪNO KULTŪROS AKADEMIJA LITHUANIAN ACADEMY OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION KŪNO KULTŪROS IR SPORTO DEPARTAMENTAS PRIE LIETUVOS RESPUBLIKOS VYRIAUSYBĖS DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION AND SPORTS UNDER THE GOVERNEMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA SPORTO MOKSLO DABARTIS IR NAUJOSIOS IDĖJOS CURRENT ISSUES AND NEW IDEAS IN SPORT SCIENCE Tarptautinė mokslinė konferencija International Scientific Conference Pranešimų tezės Abstracts 2006 m. spalio 5—6 d. 5—6 October 2006 Kaunas, Lietuva Kaunas, Lithuania KONFERENCIJĄ REMIA CONFERENCE SPONSORS LIETUVOS VALSTYBINIS MOKSLO IR STUDIJŲ FONDAS LITHUANIAN STATE SCIENCE AND STUDIES FOUNDATION LIETUVOS TAUTINIS OLIMPINIS KOMITETAS LITHUANIAN NATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE © Lietuvos kūno kultūros akademija, 2006 ISBN 9955-622-29-6 MOKSLINIS KOMITETAS SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Albertas SKURVYDAS, prof. habil. dr. Pirmininkas, Chairman, Lithuanian Academy of Physical Education Lietuvos kūno kultūros akademija (Lietuva) (Lithuania) Wolf-Dietrich BRETTSCHNEIDER, prof. dr. Paderborno universitetas (Vokietija) Universität Paderborn (Germany) Herman van COPPENOLLE, prof. dr. Liuveno katalikiškasis universitetas (Belgija) Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (Belgium) Karsten FROBERG, prof. dr. Pietų Danijos universitetas (Danija) University of Southern Denmark (Denmark) Arnold de HAAN, prof. dr. Amsterdamo Vrije universitetas (Olandija) Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (The Netherlands) Thomas REILLY, prof. dr. Liverpulio John Moores universitetas Liverpool John Moores University (Jungtinė Karalystė) (United Kingdom) David RODRIGUES, -

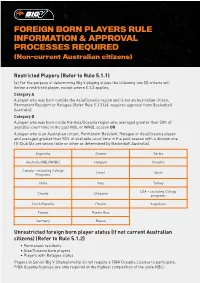

Foreign Born Players Rule Information & Approval

FOREIGN BORN PLAYERS RULE INFORMATION & APPROVAL PROCESSES REQUIRED (Non-current Australian citizens) Restricted Players (Refer to Rule 5.1.1) (a) For the purpose of determining Big V playing status the following two (2) criteria will define a restricted player, except where 5.1.2 applies; Category A A player who was born outside the Asia/Oceania region and is not an Australian citizen, Permanent Resident or Refugee (Refer Rule 5.1.3 (e)- requires approval from Basketball Australia) Category B A player who was born inside the Asia/Oceania region who averaged greater than 50% of available court time in the past NBL or WNBL season OR A player who is an Australian citizen, Permanent Resident, Refugee or Asia/Oceania player and averaged greater than 50% of available court time in the past season with a division one (1) Club (As per below table or other as determined by Basketball Australia). Argentina Greece Serbia Australia (NBL/WNBL) Hungary Slovakia Canada – excluding College Israel Spain Programs China Italy Turkey USA – excluding College Croatia Lithuania programs Czech Republic Poland Yugoslavia France Puerto Rico Germany Russia Unrestricted foreign born player status (if not current Australian citizens) (Refer to Rule 5.1.2) • Permanent residents • Asia/Oceania born players • Players with Refugee status Players in Senior Big V Championship do not require a FIBA Oceania License to participate. FIBA Oceania licenses are only required in the highest competition of the state NBL1. Australian citizenship (Refer to Rule 5.1.4) A player who gains Australian citizenship through naturalisation must lodge certificate of Australian citizenship with Big V prior to participating in the league as a non-restricted player. -

Eči Oga. Geriausi Etai a Ie Ye, Aya Bų, Uriuos Ii

Sveiiname isus Lietuvos autini imni omitet tkūrim 25-eči oga. Geriausi etai a ie y e, a y abų, uriuos ii ums isiems uveiti. Tegul na augia imnės šviesos isų ūsų abose, intyse, asavi antykiuose. Ateitis ia, Lietuvoje, s ukurt ilniu abu. Išdrįskite, painite, eiite, aykite anginite imni o o stoiją, es ai – idsis ūsų venim urtas. Reda toių ayb B wishes n e ccasin 25h nive ay f -stabished Ntina Oympi Comitte ¡ Lithuania. ¢ e £ea¤ hea¥ ¦ith §an¨ rea© ªos on n« ¦ith o Oympi iit ¬ u® ¯ ns, houghts, utua °± ² ratin. ¢ e futu ³e , ¬ Lithuania, wi´ ilt ndeµ ¶ e ·i ² r¸mance. Act ¦ith °ourag¹, ² neº ew, ¦ith iigence n« °omitmen© n» ¼a½ue ¶ e Oympi o ³istoy s ¶ e rea© ¼a½ue f u® ¾ife. Editoia Ba¿ SPORTO 2013 SPORT 4(74) MOKSLAS VILNIUS SCIENCE LIETUVOS SPORTO MOKSLO TARYBOS LIETUVOS OLIMPINĖS AKADEMIJOS LIETUVOS SPORTO UNIVERSITETO LIETUVOS EDUKOLOgIJOS UNIVERSITETO Ž U R N A L A S JOURNAL OF LITHUANIAN SPORTS SCIENCE COUNCIL, LITHUANIAN OLYMPIC ACADEMY, LITHUANIAN SPORTS UNIVERSITY AND LITHUANIAN UNIVERSITY OF Educational SCIENCES LEIDŽIAMAS nuo 1995 m.; nuo 1996 m. – prestižinis žurnalas ISSN 1392-1401 Žurnalas įtrauktas į: INDEX COPERNICUS duomenų bazę Indexed in INDEX COPERNICUS Vokietijos federalinio sporto mokslo instituto Included into German Federal Institute for Sport Science literatūros duomenų banką SPOLIT Literature data bank SPOLIT REDAKTORIŲ TARYBA TURINYS Prof. habil. dr. Eugenija ADAŠKEVIČIENĖ (Klaipėdos u-tas)) ĮVADAS // INTRODUCTION .....................................................................3 Prof. habil. dr. Marijona BARKAUSKAITĖ (LEU) Prof. habil. dr. Pavel CIęSzCzYK (Ščecino u-tas, Lenkija) A. Poviliūnas. Atkurtam Lietuvos tautiniam Doc. dr. Dainius gENYS (VDU) olimpiniam komitetui – 25-eri ...........................................................................3 Prof. -

In the Foo Tsteps of V Ic Tories

Aukštaičių g. 39 12 km 33 6 km 10 9 5 km 4 km 43 11 31 32 19 51 THE CITY OF Jonavos g. 3 km 3 km 5 km Aukštaičių g. CHAMPIONS Žalioji g. Aušros g. Savanorių pr. 18 Žemaičių g. Jonavos g. V. Putvinskio g. K. Petrausko g. 44 A. Mackevičiaus g. 5 Radastų g. Kauko al. Benediktinių g. Šv. Gertrūdos g. A. Jakšto g. Maironio g. 46 K. Donelaičio g. A. Mickevičiaus g. A. Mackevičiaus g. 25 Savanorių pr. 8 Šv. Gertrūdos g. Gedimino g. Papilio g. 24 17 Kumelių g. E. Ožeškienės g. 4 Parodos g. M. Valančiaus g. A. Mapu g. Laisvės al. 22 15 16 Laisvės al. 7 45 Laisvės al. 13 Vilniaus g. J. Gruodžio g. 47 3 Vilniaus g. Rotušės a. 45 Nemuno g. 6 2 45 49 26 48 53 Santakos g. 14 20 D. Poškos g. Kęstučio g. Birštono g. Maironio g. M. Daukšos g. 52 Kęstučio g. Muitinės g. Kurpių g. Smalininkų g. 54 DaukantoS. g. Muziejaus g. T. Daugirdo g. Nemuno g. A. Mickevičiaus g. Gedimino g. Aleksoto g. Karaliaus Mindaugo pr. L. Zamenhofo g. I. Kanto g. Karaliaus Mindaugo pr. Druskininkų g. 21 50 42 16 km Karaliaus Mindaugo pr. Miško g. 38 1 ŽALGIRIO ARENA 7 ARVYDAS SABONIS’ HOME Perkūno al. Karaliaus Mindaugo pr. 50 Vytauto pr. Vytauto The largest multifunctional arena in the Baltic While it might be difficult to be the second-coming of Arvydas Sabonis, there’s still an opportunity to live in g. Trakų states and the home of the legendary Žalgiris 23 Vaižganto g.