Official Committee Hansard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Nineteen

Chapter Six The Politics of Federalism Ben Davies In 1967 Sir Robert Menzies published Central Power in the Australian Commonwealth. In this book he adopted the labels coined by Lord Bryce to describe the two forces which operate in a federation—the centripetal and the centrifugal. For those uneducated in physics, such as myself, centripetal means those forces which draw power towards the centre, or the Commonwealth, whilst centrifugal forces are those which draw power outwards towards the States. Menzies remarked that these forces are constantly competing against each other, and that the balance between them is never static.1 Not surprisingly, his view in 1967 was that the centripetal forces had well and truly predominated during the previous 66 years of Federation. Of course, he would not need long to reach the same conclusion were he to consider the same question now, 40 years later. Essentially there are three levels on which these two forces exert themselves. The first and most fundamental is the legal level, which describes the constitutional structures which determine the federal balance. On questions of federalism this Society has since its inception quite rightly concentrated most on this level of federalism, as it is at this level that the most profound changes have occurred. It is also the most influential level, as it sets the boundaries within which the other two levels can operate. The second level is what I would call the financial level, and this level concerns itself with the question of the relative financial powers of the States and Commonwealth. In particular, this level is characterised by the ever-increasing financial dominance of the Commonwealth relative to the States, and the “vertical fiscal imbalance” with which the States have had to contend for most of their existence since Federation. -

Vol15no4.Pdf

A new award for young writers Eureka Street is delighted to announce the inaugural Margaret Dooley Young Writers' Award One of the di These arguments ideally address peo pl e who own religious be li ef, and those whose view of the world is secu lar. To reflect ethical ly on public issues is a demanding discipline. h•s field. Margaret and Brendan Dooley have longstanding connection s to the Jesuits and Xavier Co llege . Margaret always appreciated the value of commun ication and education for young people, based on spiritual and personal val ues. She graduated from Sacre Coeur College in 1950, com menced nursing at St Vin ce nt's Hospital and, with Brendan, raised four chil dren. Margaret died in 2004. The Dooley family are pleased to support th is initiative. previously published or unpublished, under the age of 40. Entrants must submit two previously unpublished articles that offer: ethical reflection directed to a non-specialist audience on any serious to pic, appeal to humane values, such as those that are found within, but are not exclusive to, the best of the Christian trad ition , clear argument and elegant expression, and a generosity and courtesy of spirit animating forceful argument. One article shou ld be of no more than 800 words. The second shoul d be of no more than 2000 words. They may take up the sa me, or different, topics. Entries are to be submitted by 5pm Friday, 29 July 2005, to : Margaret Dooley Young Writers' Award, Eureka Street, PO Box 553, Richmond VIC 3121. -

From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: a Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478

Department of the Parliamentary Library INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES •~J..>t~)~.J&~l<~t~& Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478 © Copyright Commonwealth ofAustralia 1999 Except to the exteot of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament in the course oftheir official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribntion to Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced,the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian govermnent document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staffbut not with members ofthe public. , ,. Published by the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, 1999 INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES , Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants Professor John Warhurst Consultant, Politics and Public Administration Group , 29 June 1999 Acknowledgments This is to acknowledge the considerable help that I was given in producing this paper. -

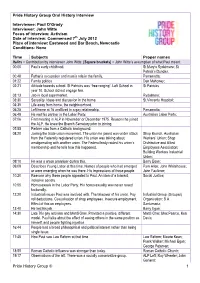

Paul O'grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus O

Pride History Group Oral History Interview Interviewee: Paul O’Grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus of interview: Activism Date of interview: Commenced 7th July 2012 Place of interview: Eastwood and Bar Beach, Newcastle Conditions: None Time Subjects Proper names Italics = Contribution by interviewer John Witte, [Square brackets] = John Witte’s assumption of what Paul meant. 00:00 Paul’s early childhood. St Mary’s Rydalmere; St Patrick’s Dundas; 00:48 Father’s occupation and mum’s role in the family. Parramatta; 01:22 Family politics. Dan Mahoney; 02:21 Attitude towards school. St Patricks was “free ranging”. Left School in St Patricks year 10. School did not engage him. 03:13 Job in local supermarket. Rydalmere; 03:30 Sexuality. Ideas and discussion in the home. St Vincents Hospital; 04:35 Life away from home, the neighbourhood. 05:25 Left home at 16 and lived in a gay relationship. Parramatta; 06:49 He met his partner in the Labor Party. Australian Labor Party; 07:06 First meeting in ALP in November or December 1975. Reasons he joined the ALP. He knew the Branch Secretary prior to joining. 07:55 Partner also from a Catholic background. 08:20 Joining the trade union movement. The union he joined was under attack Shop Branch, Australian from the Federally registered union. His union was talking about Workers’ Union; Shop amalgamating with another union. The Federal body raided his union’s Distributive and Allied membership and he tells how this happened. Employees Association; Building Workers Industrial Union; 09:10 He was a union organiser during this. -

Neville Wran. Australian Biographical Monographs No. 5, by David Clune

158 Neville Wran. Australian Biographical Monographs No. 5, by David Clune. Cleveland (Qld): Connor Court Publishing, 2020. pp. 80, Paperback RRP $19.95 ISBN: 9781922449092 Elaine Thompson Former Associate Professor, University of New South Wales. It’s been many years since I’ve thought about Neville Wran, so I came to this monograph with an oPen mind, limited by two Personal judgements. The first was the belief that Wran was a giant of his time, a real leader and moderniser. The second was the tragedy (farce) of his last years. It was a reminder to us all that there are no guarantees that a great life will be rewarded with a kind death: for Neville Wran that was certainly not the case. Luckily, now with time we remember his leadershiP, his modernising Policies and his largely successful ability to dominate an extraordinarily Powerful Political Party with its deeP factions. David Clune’s monograph, through the use of first-hand materials and comments from Wran’s colleagues, takes us through Wran’s rise to Power, his successes as Premier and his fall via the web of corruPtion and scandal that ended his Premiership. Clune’s narrative is clear and remarkably free of value-judgements. It reminds us just how moribund the Politics and Parliament of NSW were at the time leading uP to Wran’s Government and of all the talent Wran brought with him, which transformed NSW Politics, Policy and Parliament. Of course, there were failures; things left incomPlete and the embedded corruPt culture of NSW Politics largely ignored. Nonetheless, in this monograph we gain a Picture of an extraordinary man leading Australia (via NSW) into the modern era. -

NSW Legislative Council Hansard Full Day Transcript Page 1 of 3

NSW Legislative Council Hansard Full Day Transcript Page 1 of 3 NSW Legislative Council Hansard Full Day Transcript Extract from NSW Legislative Council Hansard and Papers Tuesday, 21 September 2004. The Hon. ERIC ROOZENDAAL [5.02 p.m.] (Inaugural Speech): I support the Motor Accidents Legislation Amendment Bill. Madam President and honourable members, I am named after my grandfather, a man I never knew. He perished in Auschwitz in 1944. As he was herded into a train, he threw his signet ring to a local railway worker, who later gave it to my grandmother. I proudly wear that ring today. And I hope my grandfather is watching with pride as his grandson joins the oldest Parliament in Australia—a privilege to rival my previous job as head of the oldest branch of the oldest social democratic party in the world. It is therefore with great pride that I deliver my inaugural speech. I am filling the vacancy created by the departure of Tony Burke, who will shortly be elected as a member of the Latham Labor government. I have no doubt Tony will achieve greatness in our national Parliament. I am grateful for his assistance and advice during my transition into the Legislative Council. My presence in this place owes everything to the two great causes to which I have devoted my life: my family and the Labor Party. My beautiful wife, Amanda, and my three wonderful children, Liam, Harry and Jema, are my world. Amanda is a wonderful wife and mother, and, as my partner in life, my rock of support, for which I am eternally grateful. -

Publications for David Clune 2020 2019 2018

Publications for David Clune 2020 Clune, D., Smith, R. (2019). Back to the 1950s: the 2019 NSW Clune, D. (2020), 'Warm, Dry and Green': release of the 1989 Election. Australasian Parliamentary Review, 34(1), 86-101. <a Cabinet papers, NSW State Archives and Records Office, 2020. href="http://dx.doi.org/10.3316/informit.950846227656871">[ More Information]</a> Clune, D. (2020). A long history of political corruption in NSW: and the downfall of MPs, ministers and premiers. The Clune, D. (2019). Big-spending blues. Inside Story. <a Conversation. <a href="https://theconversation.com/the-long- href="https://insidestory.org.au/big-spending-blues/">[More history-of-political-corruption-in-nsw-and-the-downfall-of-mps- Information]</a> ministers-and-premiers-147994">[More Information]</a> Clune, D. (2019). Book Review. The Hilton bombing: Evan Clune, D. (2020). Book review: 'Dead Man Walking: The Pederick and the Ananda Marga. Australasian Parliamentary Murky World of Michael McGurk and Ron Medich, by Kate Review, 34(1). McClymont with Vanda Carson. Melbourne: Vintage Australia, Clune, D. (2019). Book Review: "Run for your Life" by Bob 2019. Australasian Parliamentary Review, 34(2), 147-148. <a Carr. Australian Journal of Politics and History, 65(1), 146- href="https://www.aspg.org.au/wp- 147. <a href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ajph.12549">[More content/uploads/2020/06/Book-Review-Dead-Man- Information]</a> Walking.pdf">[More Information]</a> Clune, D. (2019). Close enough could be good enough. Inside Clune, D. (2020). Book review: 'The Fatal Lure of Politics: The Story. <a href="https://insidestory.org.au/close-enough-could- Life and Thought of Vere Gordon Childe', by Terry Irving. -

Australia: Professor Marian Simms Head, Political Studies Department

Australia: Professor Marian Simms Head, Political Studies Department University of Otago Paper prepared for presentation at the joint ANU/UBA ‘John Fogarty Seminar’, Buenos Aires, Argentina 26-27 April 2007 Please note this paper is a draft version and is not for citation at this stage 1 Overview: Australian has been characterized variously as ‘The Lucky Country’ (Donald Horne), ‘A Small Rich Industrial Country’ (Heinz Arndt), and as suffering from ‘The Tyranny of Distance’ (Geoffrey Blainey). These distinguished authors have all mentioned negatives alongside positives; for example, political commentator Donald Horne’s famous comment was meant to be ironic – Australia’s affluence, and hence stability, were founded on good luck via rich mineral resources. For Blainey, the historian, geography mattered, both in terms of the vast distances from Europe and in terms of the vast size of the country.1 For economic historian Arndt, size was a double-edged sword – Australia had done well in spite of its small population. Those commentatories were all published in the 1970s. Since then much has happened globally, namely the stock market crash of the eighties, the collapse of communism in the late eighties and early nineties, the emergence of the Asian tigers in the nineties, and the attack on New York’s twin towers in 2001. All were profound events. It is the argument of this paper that in spite of these and other challenges, Australia’s institutional fabric has incorporated economic, social and political change. This is not to say that it has solved all of its social and economic problems, especially those dealing with minority groups such as the indigenous community, disaffected youth and some immigrant groups. -

Thesis August

Chapter 1 Introduction Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? Section 1.2: Problems of sex, gender and parliament Section 1.3: Gender and the Parliament, 1995-1999 Section 1.4: Expectations on female MPs Section 1.5: Outline of the thesis Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? The Sydney Morning Herald of 27 August 1925 reported the first speech given by a female Member of Parliament (hereafter MP) in New South Wales. In the Legislative Assembly on the previous day, Millicent Preston-Stanley, Nationalist Party Member for the Eastern Suburbs, created history. According to the Herald: ‘Miss Stanley proceeded to illumine the House with a few little shafts of humour. “For many years”, she said, “I have in this House looked down upon honourable members from above. And I have wondered how so many old women have managed to get here - not only to get here, but to stay here”. The Herald continued: ‘The House figuratively rocked with laughter. Miss Stanley hastened to explain herself. “I am referring”, she said amidst further laughter, “not to the physical age of the old gentlemen in question, but to their mental age, and to that obvious vacuity of mind which characterises the old gentlemen to whom I have referred”. Members obviously could not afford to manifest any deep sense of injury because of a woman’s banter. They laughed instead’. Preston-Stanley’s speech marks an important point in gender politics. It introduced female participation in the Twenty-seventh Parliament. It stands chronologically midway between the introduction of responsible government in the 1850s and the Fifty-first Parliament elected in March 1995. -

Michael Daley Inaugural Speech.Pdf

Inaugural Speeches Inaugural Speeches Extract from NSW Legislative Assembly Hansard and Papers Wednesday 12 October 2005. Mr MICHAEL DALEY (Maroubra) [7.58 p.m.] (Inaugural speech): I would like to similarly begin by congratulating Steven Chaytor, the honourable member for Macquarie Fields, and Carmel Tebbutt, the honourable member for Marrickville, who were elected on the day I was elected. Having been elected on the same day, I believe we will always share a special bond. As a young legal student I read carefully about the development of democratic institutions in the early colony of New South Wales and I studied the social and legal history and traditions of this House, which, like many similar Chambers in the world, is the inheritor of over 700 years of history and tradition. It is with a sense of awe and great pride that I address the House now for the first time. I do not for one moment fail to appreciate that the people of Maroubra have bestowed upon me what I consider to be the greatest privilege citizens can bestow upon another in a democracy—the opportunity to be their representative in a legislature. I thank the families of Maroubra, my fellow locals, for electing me on 17 September. I have lived every day of my life in the Maroubra electorate. I will not let them down. There have been only three former members for Maroubra—and two of them have been Premiers— Robert James Heffron from the establishment of the seat in 1950 until 1968, William Henry Haig from 1968 until 1983, and Robert John Carr from 1983 until his departure earlier this year. -

Wran Lecture 2015 “Let Me Begin by Acknowledging the Traditional Owners of the Land

Wran Lecture 2015 “Let me begin by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land. I pay my respects to their elders past and present. I want to acknowledge Jill Wran’s presence here this evening. I sought Jill’s counsel in the earliest days of my leadership and I am so grateful for the advice and encouragement she gives me. The very first person I visited after I was sworn in as a Labor member of Parliament in 2010 was Neville Wran in his office in Bligh Street. I will not repeat the details of our discussion, but I can report that Paul Keating was right when he said Neville had a ‘PhD in poetic profanity.’ In May last year—along with many of Labor’s faithful and many of this state’s citizens— I went to Sydney’s Town Hall to celebrate the life and work of Neville Kenneth Wran. It was a fitting tribute, in the right place. The Sydney Town Hall was, after all, the political stage upon which Wran gave some of his most memorable performances. It was moving then. It is an honour now to deliver this year’s Wran Lecture. In 1976, the election of the Wran government came at a crucial moment in Labor’s history when, in the wake of Whitlam’s dismissal, some questioned Labor’s legitimacy. But after the rancour and tumult of 1975 Wran soon showed that Labor could still deliver ‘stable, steady, progressive government’. Wran’s success was built on a belief in the power of government to improve the lives of the people of New South Wales. -

Neville Wran – a Lawyer Politician – Reflections on Law Reform and the High Court of Australia

THE PARLIAMENT OF NEW SOUTH WALES THURSDAY, 13 NOVEMBER 2008 INAUGURAL NEVILLE WRAN LECTURE NEVILLE WRAN – A LAWYER POLITICIAN – REFLECTIONS ON LAW REFORM AND THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA The Hon Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG* NEVILLE WRAN’S LIFE & TIMES PARALLEL LIVES This is the inaugural lecture to honour Neville Wran, one of the most successful Australian politicians and lawyers of my lifetime. Over the years I have honoured parliamentarians on all sides of politics. In Melbourne, I gave the Alfred Deakin Lecture, established by those associated with the Liberal Party of Australia. In this Parliament I gave the Earle Page Lecture established to celebrate the life of a leader of the Australian Country Party. Now, the Neville Wran Lecture established by the Australian Labor Party. Yet unlike the British, from whom we otherwise derived so many conventions of political and civic life, Australians tend to observe a highly partisan view of their politicians, * Justice of the High Court of Australia. Personal views and opinions. The writer acknowledges the assistance of his associate, Leonie Young, in respect of some of the biographical materials. 2. even after they have left politics. This is an infantile disorder. We need to grow out of it and acknowledge warmly those who have contributed to our public life. In some respects, my life has run on a parallel course with Neville Wran's. We were both children of families, intelligent but not well off. We both grew up in the western suburbs of Sydney. We both attended selective public schools. We enjoyed the extra-curricula activities of university life.