Investigating the El Capitan Rock Avalanche

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 34 number 3 • 2017 Society News, Notes & Mail • 243 Announcing the Richard West Sellars Fund for the Forum Jennifer Palmer • 245 Letter from Woodstock Values We Hold Dear Rolf Diamant • 247 Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage Rebecca Conard and John H. Sprinkle, Jr., guest editors Dedication•252 Planned Obsolescence: Maintenance of the National Park Service’s History Infrastructure John H. Sprinkle, Jr. • 254 Shining Light on Civil War Battlefield Preservation and Interpretation: From the “Dark Ages” to the Present at Stones River National Battlefield Angela Sirna • 261 Farming in the Sweet Spot: Integrating Interpretation, Preservation, and Food Production at National Parks Cathy Stanton • 275 The Changing Cape: Using History to Engage Coastal Residents in Community Conversations about Climate Change David Glassberg • 285 Interpreting the Contributions of Chinese Immigrants in Yosemite National Park’s History Yenyen F. Chan • 299 Nānā I Ke Kumu (Look to the Source) M. Melia Lane-Kamahele • 308 A Perilous View Shelton Johnson • 315 (continued) Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage (cont’d) Some Challenges of Preserving and Exhibiting the African American Experience: Reflections on Working with the National Park Service and the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site Pero Gaglo Dagbovie • 323 Exploring American Places with the Discovery Journal: A Guide to Co-Creating Meaningful Interpretation Katie Crawford-Lackey and Barbara Little • 335 Indigenous Cultural Landscapes: A 21st-Century Landscape-scale Conservation and Stewardship Framework Deanna Beacham, Suzanne Copping, John Reynolds, and Carolyn Black • 343 A Framework for Understanding Off-trail Trampling Impacts in Mountain Environments Ross Martin and David R. -

Sketch of Yosemite National Park and an Account of the Origin of the Yosemite and Hetch Hetchy Valleys

SKETCH OF YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK AND AN ACCOUNT OF THE ORIGIN OF THE YOSEMITE AND HETCH HETCHY VALLEYS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY 1912 This publication may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington. I). C, for LO cents. 2 SKETCH OP YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK AND ACCOUNT OF THE ORIGIN OF THE YOSEMITE AND HETCH HETCHY VALLEYS. By F. E. MATTHES, U. S. Geological Surrey. INTRODUCTION. Many people believe that the Yosemite National Park consists principally of the Yosemite Valley and its bordering heights. The name of the park, indeed, would seem to justify that belief, yet noth ing could be further from the truth. The Yosemite Valley, though by far the grandest feature of the region, occupies only a small part of the tract. The famous valley measures but a scant 7 miles in length; the park, on the other hand, comprises no less than 1,124 square miles, an area slightly larger than the State of Rhode Island, or about one-fourth as large as Connecticut. Within this area lie scores of lofty peaks and noble mountains, as well as many beautiful valleys and profound canyons; among others, the Iletch Hetchy Valley and the Tuolumne Canyon, each scarcely less wonderful than the Yosemite Valley itself. Here also are foaming rivers and cool, swift trout brooks; countless emerald lakes that reflect the granite peaks about them; and vast stretches of stately forest, in which many of the famous giant trees of California still survive. The Yosemite National Park lies near the crest of the great alpine range of California, the Sierra Nevada. -

DEC Avalanche Preparedness in the Adirondacks Brochure (PDF)

BASIC AVALANCHE AWARENESS ADDITIONAL RESOURCES New York State Department of This brochure is designed to let the recreational Organizations Environmental Conservation user know that avalanche danger does exist in New York and gives basic ideas of what to look for U.S. Forest Service Avalanche Center PO Box 2356 and avoid. To learn more about avalanche Ketchum, Idaho, 83340 awareness consider attending professional Office Phone: (208) 622-0088 courses, reading and experience. www.fsavalanche.org Avalanche Westwide Avalanche Network Preparedness in the www.avalanche.org 1. Know basic avalanche rescue techniques. American Avalanche Association Adirondacks 2. Check the snow depth. www.avalanche.org/~aaap 3. Check how much new snow has fallen. Books 4. Practice safe route finding. Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills Published by The Mountaineer Books 5. Check the degree of the slope. Snow Sense: A Guide to Evaluating Snow Avalanche Hazard Published by Alaska Mountain Safety Center, Inc. 6. Check the terrain. 7. Carry basic avalanche rescue equipment. Thank You For Your 8. Never travel alone. Cooperation 9. Let someone know where you are going. NYSDEC - Region 5 Ray Brook, New York 12977 10. Do not be afraid to turn around. (518) 897-1200 Emergency Dispatch Number: (518) 891-0235 11. Use common sense. Visit the DEC Website at www.dec.ny.gov Photograph by: Ryland Loos Photograph by: Ryland Loos WHAT IS AN AVALANCHE? HOW CAN YOU KEEP FROM GETTING CAUGHT WHAT DO YOU DO WHEN CAUGHT IN AN IN AN AVALANCHE? AVALANCHE? An avalanche is a mass of snow sliding down a mountainside. Avalanches are also called You can reliably avoid avalanches by recognizing Surviving avalanches can depend on luck, but it is snowslides; there is no difference in these terms. -

The Politics of Information in Famine Early Warning A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Fixing Famine: The Politics of Information in Famine Early Warning A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Suzanne M. M. Burg Committee in Charge: Professor Robert B. Horwitz, Chair Professor Geoffrey C. Bowker Professor Ivan Evans Professor Gary Fields Professor Martha Lampland 2008 Copyright Suzanne M. M. Burg, 2008 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Suzanne M. M. Burg is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii DEDICATION For my past and my future Richard William Burg (1932-2007) and Emma Lucille Burg iv EPIGRAPH I am hungry, O my mother, I am thirsty, O my sister, Who knows my sufferings, Who knows about them, Except my belt! Amharic song v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………. iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………….. iv Epigraph…………………………………………………………………………. v Table of Contents………………………………………………………………... vi List of Acronyms………………………………………………………………… viii List of Figures……………………………………………………………………. xi List of Tables…………………………………………………………………….. xii Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………….. xiii Vita………………………………………………………………………………. -

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park July 29, 2015 - September 1, 2015 1, September - 2015 29, July Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where NPS Photo NPS 1904. Grove, Mariposa Monarch, Fallen the astride Soldiers” “Buffalo Cavalry 9th D, Troop Volume 40, Issue 6 Issue 40, Volume America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Shuttle Yosemite The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking Village Day-use Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Half Dome Picnic Area 11 P1 1 8836 ft North 2693 m Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Lodge Day-use Parking Pines Walk-In (Open May 22, 2015) Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Village Day-use Parking Pines Beach E7 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l E4 Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d R V iver E6 Nevada To & Fall The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Yosemite Valley Hiking Map U.S

Yosemite National Park National Park Service Yosemite Valley Hiking Map U.S. Department of the Interior To To ) S k Tioga n Tioga m e To o e k w r Road 10 Shuttle Route / Stop Road 7 Tioga . C Ranger Station C 4 n 3.I mi (year round) 6.9 mi ( Road r e i o 5.0 km y I e II.I km . 3.6 mi m n 6 k To a 9 m 5.9 km 18 Shuttle Route / Stop . C Self-guiding Nature Trail Tioga North 0 2 i Y n ( . o (summer only) 6 a Road 2 i s . d 6 m e 5.0 mi n m k i I Trailhead Parking ( 8.0 km m Bicycle / Foot Path I. it I.3 0 e ) k C m (paved) m re i ( e 2 ) ) k . Snow I Walk-in Campground m k k m Creek Hiking Trail .2 k ) Falls 3 Upper e ( e Campground i r Waterfall C Yosemite m ) 0 Fall Yosemite h I Kilometer . c r m 2 Point A k Store l 8 6936 ft . a ) y 0 2II4 m ( m I Mile o k i R 9 I. m ( 3. i 2 5 m . To Tamarack Flat North m i Yosemite Village 0 Lower (5 .2 Campground . I I Dome 2.5 mi Yosemite k Visitor Center m 7525 ft 0 Fall 3.9 km ) 2294 m . 3 k m e Cre i 2.0 mi Lower Yosemite Fall Trail a (3 To Tamarack Flat ( Medical Royal Mirror .2 0 y The Ahwahnee a m) k . -

Centennial Issue

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK Centennial Issue is been 100 years ture an appearance by since President Ben- President George Bush, jamin Harrison who has been invited. A I signed into law the number of other dig- act that established a large nitaries will also be in area around Yosemite attendance, and about Valley and the Mariposa the time of the ceremony, Big Trees as Yosemite a time capsule will be National Park. For the buried in front of the remainder of 1990 and Yosemite Valley Visitor until October, 1991, the Center. National Park Service Other centennial pro- will be celebrating the grams include a major park's centennial and ask- symposium that has been ing people to contemplate scheduled from October Yosemite's history and 13 to 19 in Concord and how the preservation Yosemite . The focus of idea, engendered in the symposium will be Yosemite, has taken on on natural and cultural new meaning in the face resource issues and on of global environmental future directions for park changes . There are hopes management. There are that from history we can also at least two museum learn the Iessons that will exhibits that will be open allow us to manage and through the end of the use Yosemite with the year. One is at the Califor- same foresight and wis- nia Academy of Sciences dom exemplified by those in San Francisco, the who first legislated the other at Yosemite 's own preservation of the place. museum . Please call the Participation in Yosemite Association at Yosemite's centennial (209) 379-2317 for infor- celebration is open to mation about any of everyone, and a variety of these programs or events. -

Controlled Avalanche – a Regulated Voluntary Exposure Approach for Addressing

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.12.20062687; this version posted April 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Controlled Avalanche – A Regulated Voluntary Exposure Approach for Addressing 2 Covid-19 ₤ 3 Eyal Klement1* DVM, Alon Klement2 SJD, David Chinitz3 PhD, Alon Harel4 Dphill, Eyal 4 Fattal5 PhD, Ziv Klausner5 PhD 5 6 1. Koret School of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Epidemiology and Public 7 Health, the Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel 8 2. Buchmann Faculty of Law, Tel-Aviv University, Israel 9 3. Department of Health Policy and Management, School of Public Health, Hebrew 10 University, Jerusalem, Israel 11 4. Phillip and Estelle Mizock Chair in Administrative and Criminal Law, The Faculty of 12 Law, the Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel 13 5. Department of Applied Mathematics, Israel Institute for Biological Research, Ness- 14 Ziona, Israel 15 ₤ 16 All authors contributed equally to the manuscript 17 18 * Corresponding author: 19 Address: Koret School of Veterinary Medicine, The Robert H. Smith Faculty of 20 Agriculture, Food and Environment, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, POB 12, 21 Rehovot 76100, Israel. 22 Tel: 972-8-9489560. Fax: 972-8-9489634 23 E-mail: [email protected] 24 25 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.12.20062687; this version posted April 22, 2020. -

Avalanche Safety Tips

Submit Education Center | Photo Gallery Contents Avalanche Awareness: 1. Why avalanche awareness? Surviving an avalanche 2. Who gets caught in avalanches? A true account 3. When and where avalanches happen 4. Anatomy of an avalanche Avalanche Books 5. Avalanche factors: what conditions cause an avalanche? Credits & Citations 6. How to determine if the snowpack is safe 7. Avalanche gear For more information, see our 8. Tips for avalanche survival list of other avalanche sites 9. Avalanche danger scale 10. Avalanche quick checks 1. Why avalanche awareness? Mountains attract climbers, skiers and tourists who scramble up and down the slopes, hoping to conquer peaks, each in their own way. Yet, to do this they must enter the timeless haunt of avalanches. For centuries, mountain dwellers and travelers have had to reckon with the deadly forces of snowy torrents descending with lightning speed down mountainsides. Researchers and experts are making progress in detection, prevention and safety measures, but avalanches still take their deadly toll throughout the world. Each year, avalanches claim more than 150 lives worldwide, a number that has been increasing over the © Richard Armstrong past few decades. Thousands more are caught in avalanches, partly buried or injured. Everyone from An avalanche in motion. snowmobilers to skiers to highway motorists are (Photograph courtesy of caught in the "White Death." Most are fortunate Richard Armstrong, National enough to survive. Snow and Ice Data Center.) This is meant to be a brief guide about the basics of avalanche awareness and safety. For more in depth information, several sources are listed under "More avalanche resources" in the last section of these pages. -

Mechanisms and Rate of Emplacement of the Half Dome Granodiorite

Mechanisms and rate of emplacement of the Half Dome Granodiorite Kyle J. Krajewski Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Allen F. Glazner Introduction Continental crust is largely composed of high-silica intrusive rocks such as granite, and understanding the mechanisms of granitic pluton emplacement is essential for understanding the formation of continental crust. With its incredible exposure, few places are comparable to the Tuolumne Intrusive Suite (TIS) in Yosemite National Park for studying these mechanisms. The TIS is interpreted as a comagmatic assemblage of concentric intrusions (Bateman and Dodge, 1970). The silica contents of the plutons increase from the margins inwards, transitioning from tonalities to granites, through both abrupt and gradational boundaries (Bateman and Chappell, 1979; Fig. 1). The age of the TIS also has a distinct trend, with the oldest rocks cropping out at the margins and the youngest toward the center. To accommodate this time variation, the TIS is hypothesized to have formed from multiple pulses of magma (Bateman and Chappell, 1979) . Understanding the volume, timing, and interaction of these pulses with one another has led to the formation of three main hypotheses to explain the evolution of the TIS. Figure 1. Simplified geologic map of the TIS. Insets of rocks on the right illustrate petrographic variation through the suite. Bateman and Chappell (1979) hypothesized that as the suite cooled, it solidified from the margins inward. Solidification of the chamber was prolonged by additional pulses of magma. These pulses expanded the chamber through erosion of the wall rock and breaking through the overlying carapace, creating a ballooning magma chamber. -

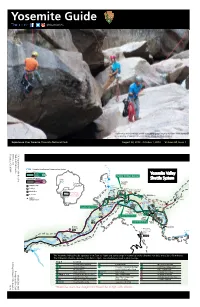

Yosemite Guide @Yosemitenps

Yosemite Guide @YosemiteNPS Yosemite's rockclimbing community go to great lengths to clean hard-to-reach areas during a Yosemite Facelift event. Photo by Kaya Lindsey Experience Your America Yosemite National Park August 28, 2019 - October 1, 2019 Volume 44, Issue 7 Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Summer-only Route: Upper Hetch Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Hetchy Shuttle Fall Yosemite Tuolumne Village Campground Meadows Lower Yosemite Parking The Ansel Fall Adams Yosemite l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area Picnic Area Valley l T Area in inset: al F e E1 t 5 Restroom Yosemite Valley i 4 m 9 The Ahwahnee Shuttle System se Yo Mirror Upper 10 3 Walk-In 6 2 Lake Campground seasonal 11 1 Wawona Yosemite North Camp 4 8 Half Dome Valley Housekeeping Pines E2 Lower 8836 ft 7 Chapel Camp Yosemite Falls Parking Lodge Pines 2693 m Yosemite 18 19 Conservation 12 17 Heritage 20 14 Swinging Center (YCHC) Recreation Campground Bridge Rentals 13 15 Reservations Yosemite Village Parking Curry Upper Sentinel Village Pines Beach il Trailhead E6 a Curry Village Parking r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M E4 ey ses erce all only d Ri V ver E5 Nevada Fall To & Bridalveil Fall d oa R B a r n id wo a a lv W e i The Yosemite Valley Shuttle operates from 7am to 10pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

1 Snow-Avalanche Impact Craters in Southern Norway: Their Morphology and 2 Dynamics Compared with Small Terrestrial Meteorite Craters

1 Snow-avalanche impact craters in southern Norway: their morphology and 2 dynamics compared with small terrestrial meteorite craters. 3 4 5 John A. Matthews1*, Geraint Owen1, Lindsey J. McEwen2, Richard A. Shakesby1, 6 Jennifer L. Hill2, Amber E. Vater1 and Anna C. Ratcliffe1 7 8 1 Department of Geography, College of Science, Swansea University, Singleton Park, 9 Swansea SA2 8PP, Wales, UK 10 11 2 Department of Geography and Environmental Management, University of the West 12 of England, Frenchay Campus, Coldharbour Lane, Bristol BS16 1QY, UK 13 14 15 * Corresponding author: [email protected] 16 17 18 ABSTRACT 19 20 This regional inventory and study of a globally uncommon landform type reveals 21 similarities in form and process between craters produced by snow-avalanche and 22 meteorite impacts. Fifty-two snow-avalanche impact craters (mean diameter 85 m, 23 range 10–185 m) were investigated through field research, aerial photographic 24 interpretation and analysis of topographic maps. The craters are sited on valley 25 bottoms or lake margins at the foot of steep avalanche paths (α = 28–59°), generally 26 with an easterly aspect, where the slope of the final 200 m of the avalanche path (β) 27 typically exceeds ~15°. Crater diameter correlates with the area of the avalanche start 28 zone, which points to snow-avalanche volume as the main control on crater size. 29 Proximal erosional scars (‘blast zones’) up to 40 m high indicate up-range ejection of 30 material from the crater, assisted by air-launch of the avalanches and impulse waves 31 generated by their impact into water-filled craters.