Mechanisms and Rate of Emplacement of the Half Dome Granodiorite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 34 number 3 • 2017 Society News, Notes & Mail • 243 Announcing the Richard West Sellars Fund for the Forum Jennifer Palmer • 245 Letter from Woodstock Values We Hold Dear Rolf Diamant • 247 Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage Rebecca Conard and John H. Sprinkle, Jr., guest editors Dedication•252 Planned Obsolescence: Maintenance of the National Park Service’s History Infrastructure John H. Sprinkle, Jr. • 254 Shining Light on Civil War Battlefield Preservation and Interpretation: From the “Dark Ages” to the Present at Stones River National Battlefield Angela Sirna • 261 Farming in the Sweet Spot: Integrating Interpretation, Preservation, and Food Production at National Parks Cathy Stanton • 275 The Changing Cape: Using History to Engage Coastal Residents in Community Conversations about Climate Change David Glassberg • 285 Interpreting the Contributions of Chinese Immigrants in Yosemite National Park’s History Yenyen F. Chan • 299 Nānā I Ke Kumu (Look to the Source) M. Melia Lane-Kamahele • 308 A Perilous View Shelton Johnson • 315 (continued) Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage (cont’d) Some Challenges of Preserving and Exhibiting the African American Experience: Reflections on Working with the National Park Service and the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site Pero Gaglo Dagbovie • 323 Exploring American Places with the Discovery Journal: A Guide to Co-Creating Meaningful Interpretation Katie Crawford-Lackey and Barbara Little • 335 Indigenous Cultural Landscapes: A 21st-Century Landscape-scale Conservation and Stewardship Framework Deanna Beacham, Suzanne Copping, John Reynolds, and Carolyn Black • 343 A Framework for Understanding Off-trail Trampling Impacts in Mountain Environments Ross Martin and David R. -

Centennial Issue

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK Centennial Issue is been 100 years ture an appearance by since President Ben- President George Bush, jamin Harrison who has been invited. A I signed into law the number of other dig- act that established a large nitaries will also be in area around Yosemite attendance, and about Valley and the Mariposa the time of the ceremony, Big Trees as Yosemite a time capsule will be National Park. For the buried in front of the remainder of 1990 and Yosemite Valley Visitor until October, 1991, the Center. National Park Service Other centennial pro- will be celebrating the grams include a major park's centennial and ask- symposium that has been ing people to contemplate scheduled from October Yosemite's history and 13 to 19 in Concord and how the preservation Yosemite . The focus of idea, engendered in the symposium will be Yosemite, has taken on on natural and cultural new meaning in the face resource issues and on of global environmental future directions for park changes . There are hopes management. There are that from history we can also at least two museum learn the Iessons that will exhibits that will be open allow us to manage and through the end of the use Yosemite with the year. One is at the Califor- same foresight and wis- nia Academy of Sciences dom exemplified by those in San Francisco, the who first legislated the other at Yosemite 's own preservation of the place. museum . Please call the Participation in Yosemite Association at Yosemite's centennial (209) 379-2317 for infor- celebration is open to mation about any of everyone, and a variety of these programs or events. -

Investigating the El Capitan Rock Avalanche

BY GREG STOCK INVESTIGATING THE EL CapITAN ROCK AVALANCHE t 2:25 on the morning of March 26, 1872, one of avalanche, an especially large rockfall or rockslide that the largest earthquakes recorded in California extends far beyond the cliff where it originated. Most Ahistory struck along the Owens Valley fault near Yosemite Valley rockfall debris accumulates at the base the town of Lone Pine just east of the Sierra Nevada. The of the cliffs, forming a wedge-shaped deposit of talus. earthquake leveled most buildings in Lone Pine and sur- Occasionally, however, debris from a rock avalanche will rounding settlements, and killed 23 people. Although extend out much farther across the valley floor. seismographs weren’t yet available, the earthquake is esti- Geologist Gerald Wieczorek of the U.S. Geological mated to have been about a magnitude 7.5. Shock waves Survey and colleagues have identified at least five rock from the tembler radiated out across the Sierra Nevada. avalanche deposits in Yosemite Valley. The largest of these On that fateful morning, John Muir was sleeping in occurred in Tenaya Canyon, at the site of present-day a cabin near Black’s Hotel on the south side of Yosemite Mirror Lake. Sometime in the past, a rock formation on Valley, near present-day Swinging Bridge. The earth- the north wall of the canyon just east of and probably quake shook the naturalist out of bed. Realizing what similar in size to Washington Column collapsed into was happening, Muir bolted outside, feeling “both glad Tenaya Canyon. The rock debris piled up against the and frightened” and shouting “A noble earthquake!” He south canyon wall to a depth of over 100 feet. -

THE YOSEMITE by John Muir CHAPTER I The

THE YOSEMITE By John Muir CHAPTER I The Approach to the Valley When I set out on the long excursion that finally led to California I wandered afoot and alone, from Indiana to the Gulf of Mexico, with a plant-press on my back, holding a generally southward course, like the birds when they are going from summer to winter. From the west coast of Florida I crossed the gulf to Cuba, enjoyed the rich tropical flora there for a few months, intending to go thence to the north end of South America, make my way through the woods to the headwaters of the Amazon, and float down that grand river to the ocean. But I was unable to find a ship bound for South America--fortunately perhaps, for I had incredibly little money for so long a trip and had not yet fully recovered from a fever caught in the Florida swamps. Therefore I decided to visit California for a year or two to see its wonderful flora and the famous Yosemite Valley. All the world was before me and every day was a holiday, so it did not seem important to which one of the world's wildernesses I first should wander. Arriving by the Panama steamer, I stopped one day in San Francisco and then inquired for the nearest way out of town. "But where do you want to go?" asked the man to whom I had applied for this important information. "To any place that is wild," I said. This reply startled him. He seemed to fear I might be crazy and therefore the sooner I was out of town the better, so he directed me to the Oakland ferry. -

Ley, So the Still Deeper Cañon of Lower Two Miles,That Is, Beyond Rather Than

THE CANON OF YOSEMITE 87 As Merced Cañon forms the southeast branch of Yosemite Val- ley, so the still deeper cañon of Tenaya Creek isits northeastern arm.Here the glacial story is less plain, and on first sight, from the heights on either side, it might be overlooked.For above the cañon's lower two miles,that is, beyond the foot of Mt. Watkins,it crowds to a narrow box-cañon between that great cliff and the steep incline of Clouds Rest.This might seem to be a V-shaped, stream-cut gorge, rather than to have the broader bottom commonly left by a glacier. But alittle exploration discovers glacial footprints in the terminal moraines and the lakes and filled lake-beds,withfineconnecting waterfalls, that mark aglacier's descent from the Cathedral Peak Range, south of the Tuolumne. We Overhung at Summit of the Half Dont,-. nrart have hardly entered the cañon, in- a tulle above the Valley floor nn.l Tena-u deed, before we are reminded of (allan.El Caption Is seen in the tllatanee. El Capitan moraine and the enclosed Yosemite Lake. A similar boulder ridge, thrown across the cañon here, is traversed by the road as it carries visitors on their early morning trips to see the sunrise reflections in Mirror Lake.This lakelet evidently occupies the lowermost of the glacial steps.It is a mere reminder of its former size, the delta of Tenaya Creek having stolen a mile from its upper end.Farther up the cañon, below and above Mt. Watkins, stream sediment has already turned similar lakes into meadows. -

Yosemite Valley Visitor Center

k e k e e r e C r Upper C n Yosemite o h y c r Fall n k A a e C e l r Yosemite Point a n C 6936ft y a Lower o 2114m i North Dome e d R t 7525ft i Yosemite n I 2294m m Fall e s ek o re Y U.S. Yosemite Valley Visitor Center C ya Court a Wilderness Center n e Museum Royal Arch T Lower Yosemite Medical Clinic Cascade Fall Trail Washington Columbia YOSEMITE Column Mirror Rock VILLAGE ROYAL Eagle Lake T ARCHES 4094ft Peak H 1248m 7779ft R The Ahwahnee Half Dome 2371m Sentinel Visitor E 8836ft Bridge Parking E North 2693m B Housekeeping Pines Camp 4 R Yosemite Camp Lower O Lodge Pines Chapel Stoneman T Bridge Middle H LeConte Brother E Memorial Road open ONLY to R Lodge pedestrians, bicycles, Ribbon S Visitor Parking and vehicles with Fall Swinging Bridge Curry Village Upper wheelchair emblem Pines Lower placards Sentinel Little Yosemite Valley El Capitan Brother Beach Trailhead for Moran 7569ft Four Mile Trail (summer only) R Point Staircase Mt Broderick i 2307m Trailhead 6706ft 6100 ft b Falls Horse Tail Parking 1859m b 2044m o Fall Trailhead for Vernal n Fall, Nevada Fall, and Glacier Point El Capitan Vernal C 7214 ft Nature Center John Muir Trail r S e e 2199 m at Happy Isles Fall Liberty Cap e n r k t 5044ft 7076ft ve i 4035ft Grizzly Emerald Ri n rced e 1230m 1538m 2157m Me l Peak Pool Silver C Northside Drive ive re Sentinel Apron Dr e North one-way Cathedral k El Capitan e Falls 0 0.5 Kilometer id To Tioga Road, Tuolumne Meadows Bridge Beach hs y ed R ut a y J and Hwy 120; and Hetch Hetchy Merc iv So -w horse trail onl o 0 0.5 Mile er -

BEDROCK GEOLOGY of the YOSEMITE VALLEY AREA YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK, CALIFORNIA Prepared by N

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP I-1639 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BEDROCK GEOLOGY OF THE YOSEMITE VALLEY AREA YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK, CALIFORNIA Prepared by N. King Huber and Julie A. Roller From the writings of Frank C. Calkins and other sources PREFACE INTRODUCTION Frank Calkins' work in Yosemite was preceded by Yosemite Valley, one of the world's great natural works Henry W. Turner, also of the U.S. Geological Survey, of rock sculpture, is carved into the west slope of the who began mapping the Yosemite and Mount Lyell 30- Sierra Nevada. Immense cliffs, domes, and waterfalls minute quadrangles in 1897 and laid the foundation that tower over forest, meadows, and a meandering river, Calkins' work was built on. Although Turner never creating one of the most scenic natural landscapes in completed this sizable assignment, he recognized the North America (fig. 1). In Yosemite Valley and the differing types of plutonic rocks and, for example, named adjoining uplands, the forces of erosion have exposed, the El Capitan Granite. with exceptional clarity, a highly complex assemblage of Calkins mapped the valley and adjacent areas of granitic rocks. The accompanying geologic map shows the Yosemite National Park during the period 1913 through distribution of some of the different rocks that make up 1916, at the same time that Francois Matthes was this assemblage. This pamphlet briefly describes those studying the glacial geology of Yosemite. Calkins rocks and discusses how they differ, both in composition summarized the bedrock geology of part of Yosemite in and structure, and the role they played in the evolution the appendix of Matthes' classic volume "Geologic History of the valley. -

LITERARY NONFICTION and the NATIONAL PARK MOVEMENT, 1864-PRESENT Lindsay Dunne

Abstract Title of Dissertation: DEFINING PLACES: LITERARY NONFICTION AND THE NATIONAL PARK MOVEMENT, 1864-PRESENT Lindsay Dunne Jacoby, Doctor of Philosophy, 2014 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jeanne Fahnestock and Professor Scott Wible Department of English The canon of American “Nature writing” has long been recognized for its influence on environmental policy, but the role of specific works in shaping environmental discourse and altering material circumstances has yet to be fully understood, especially from a rhetorical perspective. In response, this dissertation explores how works of Nature writing have functioned as persuasive arguments of definition within the National Park movement. It analyzes how literary nonfiction texts promoted a public understanding of specific landscapes and redefined them as worthy of preservation. The idea of rhetorical ecology underlies this analysis: rather than relying on the commonplace idea that a single author writing a single text can influence an environmental policy, the dissertation traces how a work of literary nonfiction operates within a complex system of texts, writers, readers, institutions, objects, and history. The four main case studies demonstrate how new definitions of place have emerged through works of literary nonfiction, each acting in relationship to a larger campaign that led to the preservation of an American landscape as a National Park: Yosemite, Great Smoky Mountains, Everglades, and Voyageurs. In these landmark campaigns, a prominent work of Nature writing, by a prominent author like John Muir, Horace Kephart, Marjory Stoneman Douglas, and Sigurd Olson, built upon and contributed to a definitional discourse that enabled people to see a specific landscape differently than it had been seen before. -

The Role of Wildfire in Shaping the Structure and Function of California ‘Mediterranean’ Stream-Riparian Ecosystems in Yosemite National Park

The role of wildfire in shaping the structure and function of California ‘Mediterranean’ stream-riparian ecosystems in Yosemite National Park DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Breeanne Kathleen Jackson Graduate Program in Environment and Natural Resources The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: S. Mažeika P. Sullivan, Advisor Amanda D. Rodewald Desheng Liu Copyrighted by Breeanne Kathleen Jackson 2015 Abstract Although fire severity has been shown to be a key disturbance to stream-riparian ecosystems in temperate zones, the effects of fire severity on stream-riparian structure and function in Mediterranean-type systems remains less well resolved. Mediterranean ecosystems of California are characterized by high interannual variability in precipitation and susceptibility to frequent high-intensity wildfires. From 2011 to 2014, I investigated the influence of wildfire occurring in the last 3-15 years across 70 study reaches on stream-riparian ecosystems in Yosemite National Park (YNP), located in the central Sierra Nevada, California, USA. At 12 stream reaches paired by fire-severity (one high- severity burned, one low-severity burned), I found no significant differences in riparian plant community structure and composition, stream geomorphology, or benthic macroinvertebrate density or community composition. Tree cover was significantly lower at reaches burned with high-severity fire, however this is expected because removal of the conifer canopy partly determined study-reach selection. Further, I found no difference in density, trophic position, mercury (Hg) body loading, or reliance on aquatically- derived energy (i.e., nutritional subsidies derived from benthic algal pathways) of/by riparian spiders of the family Tetragnathidae, a streamside consumer that can rely heavily on emerging aquatic insect prey. -

Yosemite Spring Fling

Santa Ana College Community Services Program Presents.... YOSEMITE SPRING FLING FEATURING 2 NIGHTS AT THE TENAYA LODGE, WATERFALLS & THE SUGAR PINE RAILROAD APRIL 28-30, 2013 ~ 3 DAY TOUR Via TOUR PACE ACTIVITY LEVEL AY Y AY TINERARY Leisurely On the Go Low High ~D B D I ~ Yosemite is magnificent in the Spring! Renowned for TOUR HIGHLIGHTS its magnificent valley, great granite domes and peaks, w Two nights at the Tenaya Lodge at Yosemite – waterfalls and giant sequoias, Yosemite National an elegant and secluded 4-star mountain Park is a national treasure. This 3-day getaway offers resort featuring an indoor pool and spa a truly wonderful combination of natural wonders, w Extensive guided sightseeing with a local spring bloom and rustic elegance with two nights at guide to see Yosemite Valley to see the beauty the Tenaya Lodge. of El Capitan, Half Dome and the spectac- ular waterfalls – overflowing this time of year w Ride the rails through the Sierra Nevada Tenaya Lodge Lobby Forest’s majestic woods aboard the historic narrow gauge Yosemite Mountain Sugar Pine wDAY 2 ~ YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARKw Railroad Following an included breakfast buffet at the w A traditional Basque lunch in the Central Valley hotel, a local guide will join us for the day to provide a guided tour of the Yosemite Valley. FINE HOTELS / GREAT LOCATIONS Welcome to Yosemite National Park, embracing Yosemite Valley a spectacular tract of of mountain-and-valley scen- w Nights 1-2 Tenaya Lodge at Yosemite ery in the Sierra Nevada. Set aside as a national Yosemite South Entrance, CA wDAY 1 ~ ARRIVE YOSEMITEw park in 1890, the park harbors a grand collection After meeting at our departure points this TOUR INCLUSIONS of waterfalls, meadows and forests. -

John Muir Writings My First Summer in the Sierra

‘My First Summer in the Sierra’ by John Muir (1911) - John Muir Writings A - Art Online Discussion Home FAQ Muir Weather Maps Lodging About Search Tweet Like 26 Z Prints Library Forum John Muir Writings Muir-o-Matic: Search Muir Writings John Muir Exhibit CalHotels.US Lowest Hotel Rates Guaranteed. Click Here For Yours! Hotel photos, maps, reviews, & discount rates. U.S. Hotels in California (Yosemite, L. A., San Francisco ), AL, AK, AR, AS, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DC, DE, FL, FM, GA, GU, HI, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, MN, MS, MO, MT, NE, NH, NJ, NY, OK, NV, MH, MP, NM, NC, ND, OH, OR, PA, PR, PW, RI, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, VA, VI WA, WV, WI, WY John Muir Writings My First Summer in the Sierra by John Muir (1911) Contents 1. Through the Foothills with a Flock of Sheep 2. In Camp on the North Fork of the Merced 3. A Bread Famine 4. To the High Mountains 5. The Yosemite 6. Mount Hoffman and Lake Tenaya 7. A Strange Experience 8. The Mono Trail 9. Bloody Canon and Mono Lake 10. The Tuolumne Camp 11. Back to the Lowlands http://www.yosemite.ca.us/john_muir_writings/my_first_summer_in_the_sierra/[5/3/2013 4:05:48 PM] ‘My First Summer in the Sierra’ by John Muir (1911) - John Muir Writings Liberty Cap, with Vernal and Nevada Falls With Illustrations from Drawings made by the Author in 1869 and from Photographs by Herbert W. Gleason Houghton Mifflin Company Boston and New York The Riverside Press Cambridge Published June 1911 Copyright, 1911, by John Muir All Rights Reserved To The Sierra Club of California, Faithful Defender of the People’s Playgrounds Illustrations in the Text Plates Reproduced from photographs by Herbert W. -

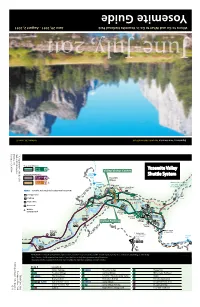

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite June 29, 2011 - August 2, 2011 2, August - 2011 29, June Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where June-July, 2011 June-July, Volume 36, Issue 5 Issue 36, Volume Park National Yosemite America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Mirror Lake Loop is Shuttle Yosemite currently closed due The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl to rockfall i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Picnic Area 11 P1 1 North Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Pines Walk-In Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Visitor Parking Pines Beach E5 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l Mist Trai Cathedral rail p T E4 Beach oo ho y L rse lle s onl Va y The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order.