The Revolution of the Women Without Anything, Without a Name

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spanish Anarchists: the Heroic Years, 1868-1936

The Spanish Anarchists THE HEROIC YEARS 1868-1936 the text of this book is printed on 100% recycled paper The Spanish Anarchists THE HEROIC YEARS 1868-1936 s Murray Bookchin HARPER COLOPHON BOOKS Harper & Row, Publishers New York, Hagerstown, San Francisco, London memoria de Russell Blackwell -^i amigo y mi compahero Hafold F. Johnson Library Ceirtef' "ampsliire College Anrteret, Massachusetts 01002 A hardcover edition of this book is published by Rree Life Editions, Inc. It is here reprinted by arrangement. THE SPANISH ANARCHISTS. Copyright © 1977 by Murray Bookchin. AH rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission except in the case ofbrief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address ftee Life Editions, Inc., 41 Union Square West, New York, N.Y. 10003. Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published 1978 ISBN: 0-06-090607-3 78 7980 818210 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 21 Contents OTHER BOOKS BY MURRAY BOOKCHIN Introduction ^ Lebensgefahrliche, Lebensmittel (1955) Prologue: Fanelli's Journey ^2 Our Synthetic Environment (1%2) I. The "Idea" and Spain ^7 Crisis in Our Qties (1965) Post-Scarcity Anarchism (1971) BACKGROUND MIKHAIL BAKUNIN 22 The Limits of the Qty (1973) Pour Une Sodete Ecologique (1976) II. The Topography of Revolution 32 III. The Beginning THE INTERNATIONAL IN SPAIN 42 IN PREPARATION THE CONGRESS OF 1870 51 THE LIBERAL FAILURE 60 T'he Ecology of Freedom Urbanization Without Cities IV. The Early Years 67 PROLETARIAN ANARCHISM 67 REBELLION AND REPRESSION 79 V. -

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939 Sam Dolgoff (editor) 1974 Contents Preface 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introductory Essay by Murray Bookchin 9 Part One: Background 28 Chapter 1: The Spanish Revolution 30 The Two Revolutions by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 30 The Bolshevik Revolution vs The Russian Social Revolution . 35 The Trend Towards Workers’ Self-Management by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 36 Chapter 2: The Libertarian Tradition 41 Introduction ............................................ 41 The Rural Collectivist Tradition by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 41 The Anarchist Influence by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 44 The Political and Economic Organization of Society by Isaac Puente ....................................... 46 Chapter 3: Historical Notes 52 The Prologue to Revolution by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 52 On Anarchist Communism ................................. 55 On Anarcho-Syndicalism .................................. 55 The Counter-Revolution and the Destruction of the Collectives by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 56 Chapter 4: The Limitations of the Revolution 63 Introduction ............................................ 63 2 The Limitations of the Revolution by Gaston Leval ....................................... 63 Part Two: The Social Revolution 72 Chapter 5: The Economics of Revolution 74 Introduction ........................................... -

The Tragic Week, Spain 1909 - Murray Bookchin

The tragic week, Spain 1909 - Murray Bookchin Murray Bookchin's history of the "tragic week": a spontaneous workers' uprising in Catalonia, Spain, which was isolated and crushed by the government, leaving hundreds dead. The collapse of the Catalan unions after the general strike of 1902 shifted the center of conflict [between workers and employers] from the economic to the political arena. In the next few years, the workers of Barcelona were to shift their allegiances from the unions to Lerroux's Radical Party. The Radical Party was not merely a political organization; it was also a man, Alejandro Lerroux y Garcia, and an institutionalized circus for plebeians. On the surface, Lerroux was a Radical Republican in the tradition of Ruiz Zorrilla: bitterly anticlerical and an opponent of Catalan autonomy. Lerroux's tactics, like Ruiz's, centered around weaning the army and the disinherited from the monarchy to the vision of a Spanish republic. In his younger days, Lerroux may have sincerely adhered to this program. The son of an army veterinary surgeon, he became a deft journalist who could mesmerize any plebeian audience or readership. After moving from Madrid to Barcelona in 1901, Lerroux openly wooed the army officers while at the same time, in the exaltado tradition of the old Republican insurrectionaries, shopped around Europe looking for arms. Had he found them, however, he probably would never have used them. His main goal was not insurrection but the revival of the dying Republican movement with transfusions of working-class support. This he achieved with dramatic public rallies, violently demagogic oratory, and a network of more than fifty public centers in Barcelona alone. -

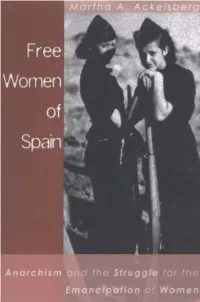

Ackelsberg L

• • I I Free Women of Spain Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women I Martha A. Ackelsberg l I f I I .. AK PRESS Oakland I West Virginia I Edinburgh • Ackelsberg. Martha A. Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women Lihrary of Congress Control Numher 2003113040 ISBN 1-902593-96-0 Published hy AK Press. Reprinted hy Pcrmi"inn of the Indiana University Press Copyright 1991 and 2005 by Martha A. Ackelsherg All rights reserved Printed in Canada AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612-1163 USA (510) 208-1700 www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh. EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555-5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] The addresses above would be delighted to provide you with the latest complete AK catalog, featur ing several thousand books, pamphlets, zines, audio products, videos. and stylish apparel published and distributed bv AK Press. A1tern�tiv�l�! Uil;:1t r\llr "-""'l:-,:,i!'?� f2":' �!:::: :::::;:;.p!.::.;: ..::.:.:..-..!vo' :uh.. ,.",i. IIt;W� and updates, events and secure ordering. Cover design and layout by Nicole Pajor A las compafieras de M ujeres Libres, en solidaridad La lucha continua Puiio ell alto mujeres de Iberia Fists upraised, women of Iheria hacia horiz,ontes prePiados de luz toward horizons pregnant with light por rutas ardientes, on paths afire los pies en fa tierra feet on the ground La frente en La azul. face to the blue sky Atirmondo promesas de vida Affimling the promise of life desafiamos La tradicion we defy tradition modelemos la arcilla caliente we moLd the warm clay de un mundo que nace del doLor. -

Levy, Carl. 2017. Malatesta and the War Interventionist Debate 1914-1917: from the ’Red Week’ to the Russian Revolutions

Levy, Carl. 2017. Malatesta and the War Interventionist Debate 1914-1917: from the ’Red Week’ to the Russian Revolutions. In: Matthew S. Adams and Ruth Kinna, eds. Anarchism, 1914-1918: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 69-92. ISBN 9781784993412 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/20790/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] 85 3 Malatesta and the war interventionist debate 1914–17: from the ‘Red Week’ to the Russian revolutions Carl Levy This chapter will examine Errico Malatesta’s (1853–1932) position on intervention in the First World War. The background to the debate is the anti-militarist and anti-dynastic uprising which occurred in Italy in June 1914 (La Settimana Rossa) in which Malatesta was a key actor. But with the events of July and August 1914, the alliance of socialists, republicans, syndicalists and anarchists was rent asunder in Italy as elements of this coalition supported intervention on the side of the Entente and the disavowal of Italy’s treaty obligations under the Triple Alliance. Malatesta’s dispute with Kropotkin provides a focus for the anti-interventionist campaigns he fought internationally, in London and in Italy.1 This chapter will conclude by examining Malatesta’s discussions of the unintended outcomes of world war and the challenges and opportunities that the fracturing of the antebellum world posed for the international anarchist movement. -

The Spanish Civil War

This is a repository copy of The Spanish Civil War. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/128173/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Yeoman, J.M. orcid.org/0000-0002-0748-1527 (2018) The Spanish Civil War. In: Levy, C. and Adams, M., (eds.) The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. Palgrave Macmillan , pp. 429-448. ISBN 9783319756196 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_25 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The Spanish Civil War* James Michael Yeoman The Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939 was one of the most significant moments in the history of anarchism. The outbreak of the conflict sparked a revolution, in which women and men inspired by anarchist ideas took control of the streets of Barcelona and the fields of Aragon. For perhaps the first, and last, time in history, libertarian communism appeared to be imminent, if not already in effect. -

Towards a History of Anarchist Anti-Imperialism

Zabalaza Anarchist “In this struggle, only the Communist Federation workers and peasants will go WHAT IS THE ZABFED? all the way to the end” The Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Federation (ZACF or simply ZabFed) is a federation of anarchist collectives and indi- viduals from the southern regions of Africa who identify with the communist tradition within Anarchism. The federation is organised around the principles of theoretical and tactical unity, collective responsibility and federalism. Our activities include study and theoretical development, anarchist agitation and propaganda, and participation within the class struggle. As anarchist-communists, we struggle for a classless, state- less and non-hierarchical society. We envision an international confederation of directly democratic, self-managed communi- ties and workplaces; a society where all markets, exchange value systems and divisions of labour have been abolished and the means of production, distribution and communication are taken over by the workers and placed under workers' self-man- agement (socialised) in order to allow for the satisfaction of the needs of everyone, adhering to the communist principle: “From each according to ability, to each according to need.” a Towards a A AN AZ AR History L C A H B IS Post: Postnet Suite 116, Private Bag X42, A T Z Braamfontein, 2017, Johannesburg, of Anarchist South Africa C O N Email: [email protected] M IO Anti-Imperialism M T UN RA IST FEDE Zabalaza Anarchist www.zabalaza.net Communist Federation 49. On Connolly and Larkin, see E. O’Connor, 1988, Syndicalism in Ireland, Towards a History 1917-23, Cork University Press, Ireland. I do not intend to enter into a detailed debate over Connolly in this paper, except to state that the recurrent attempts to appropriate Connolly for Stalinism, Trotskyism and/or the Marxist tradition, of Anarchist more generally - not to mention Irish nationalism and/or Catholicism - are con- founded by Connolly’s own unambiguous views on revolutionary unionism after 1904: see the materials in collections such as O. -

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer Raids to the Sixties by Andrew Cornell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social and Cultural Analysis Program in American Studies New York University January, 2011 _______________________ Andrew Ross © Andrew Cornell All Rights Reserved, 2011 “I am undertaking something which may turn out to be a resume of the English speaking anarchist movement in America and I am appalled at the little I know about it after my twenty years of association with anarchists both here and abroad.” -W.S. Van Valkenburgh, Letter to Agnes Inglis, 1932 “The difficulty in finding perspective is related to the general American lack of a historical consciousness…Many young white activists still act as though they have nothing to learn from their sisters and brothers who struggled before them.” -George Lakey, Strategy for a Living Revolution, 1971 “From the start, anarchism was an open political philosophy, always transforming itself in theory and practice…Yet when people are introduced to anarchism today, that openness, combined with a cultural propensity to forget the past, can make it seem a recent invention—without an elastic tradition, filled with debates, lessons, and experiments to build on.” -Cindy Milstein, Anarchism and Its Aspirations, 2010 “Librarians have an ‘academic’ sense, and can’t bare to throw anything away! Even things they don’t approve of. They acquire a historic sense. At the time a hand-bill may be very ‘bad’! But the following day it becomes ‘historic.’” -Agnes Inglis, Letter to Highlander Folk School, 1944 “To keep on repeating the same attempts without an intelligent appraisal of all the numerous failures in the past is not to uphold the right to experiment, but to insist upon one’s right to escape the hard facts of social struggle into the world of wishful belief. -

Models of Revolution: Rural Women and Anarchist Collectivisation in Civil War Spain

The Journal of Peasant Studies ISSN: 0306-6150 (Print) 1743-9361 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fjps20 Models of revolution: Rural women and anarchist collectivisation in civil war Spain Martha A. Ackelsberg To cite this article: Martha A. Ackelsberg (1993) Models of revolution: Rural women and anarchist collectivisation in civil war Spain, The Journal of Peasant Studies, 20:3, 367-388, DOI: 10.1080/03066159308438514 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03066159308438514 Published online: 05 Feb 2008. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 88 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fjps20 Download by: [JISC Collections] Date: 23 May 2016, At: 07:31 Models of Revolution: Rural Women and Anarchist Collectivisation in Civil War Spain MARTHA A. ACKELSBERG This article explores revolutionary activities in rural Spain during the years of the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), comparing two different (anarchist) perspectives on the nature of women's subor- dination and empowerment. One - evident in the activities of the mainstream anarcho-syndicalist movement - understood women's subordination to be rooted in her economic domination and, consequently, viewed economic participation as the route to empowerment. The second — developed in the anarchist women's organisation, Mujeres Libres - understood women's subordina- tion to have broader cultural roots, and, consequently, saw the need for a multi-faceted programme of education and empower- ment as key to women's liberation. The article examines the agricultural collectivisation sponsored by the CNT, as well as the activities of Mujeres Libres, comparing the successes and failures of each approach. -

The Effect of Communist Party Policies on the Outcome of the Spanish Civil War

The Effect of Communist Party Policies on the Outcome of the Spanish Civil War A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation with research distinction in Spanish in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Barbara Colberg The Ohio State University May 2007 Project Advisor: Dr. Stephen Summerhill, Department of Spanish and Portguese TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Topic Page I. Introduction 3 II. Europe and Spain Prior to the Spanish Civil War 4 III. The History of Communism in Spain 13 IV. Outbreak of the Spanish Civil War and Intervention of 28 Foreign Powers V. Communist Party Involvement in the Spanish Civil War 32 VI. Conclusion 51 Bibliography 54 2 I. INTRODUCTION The scars left by the Spanish Civil War and the ensuing 36 years of Franquist rule are still tangible in the culture of Spain today. In fact, almost 70 years after the conclusion of the conflict, the Civil War remains the most defining event in modern Spanish history. Within the confines of the three-year conflict, however, the internal “civil war” that raged amongst the various leftist groups played a very important role in the ultimate outcome of the war. The Spanish Civil War was not simply a battle between fascism and democracy or fascism and communism as it was often advertised to be. Soldiers and militiamen on both sides fought to defend many different ideologies. Those who fought for the Republican Army believed in anarchism, socialism, democracy, communism, and many other philosophies. The Soviet Union and the Spanish Communist Party were very involved in both the political situation prior to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War and in the war itself. -

Redalyc.PARALLEL TRANSFORMATIONS: LABOR and GOVERNMENT in ARGENTINA, 1915-1922

Revista de Ciencias Sociales (Cl) ISSN: 0717-2257 [email protected] Universidad Arturo Prat Chile Starosta Galante, John PARALLEL TRANSFORMATIONS: LABOR AND GOVERNMENT IN ARGENTINA, 1915-1922 Revista de Ciencias Sociales (Cl), núm. 30, 2013, pp. 9-44 Universidad Arturo Prat Tarapacá, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=70828139001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative PARALLEL TRANSFORMATIONS: LABOR AND GOVERNMENT IN ARGENTINA, 1915-19221 John Starosta Galante2 El presente artículo aborda las primeras etapas de la colaboración trabajadores- gobierno en la Argentina en fines de la década de 1910 e inicios de 1920. Se analiza la experiencia del Movimiento Sindical que en 1915 mantenía el liderazgo en la Federación Regional de Trabajadores de Argentina, anteriormente controlada por las tendencias anarquistas. Se observa centralmente el proceso durante un periodo de muy controvertidos encuentros entre los sindicatos y el Partido Radical, que en 1916 gana la elección presidencial Argentina, dando fin a un periodo de cuatro décadas de dominio del Partido Autonomista Nacional. Una vez en el poder, Sindicalistas y Radicales se involucraron en una (inconsistente y oportunista, si se quiere) colaboración sin predecentes. Palabras claves: Argentina, Buenos Aires, Sindicalismo, -

The Friends of Durruti Withdrew the Charge of Betrayal for the Sake of Anarchist Revolutionary Unity

TheThe FriendsFriends ofof DurrutiDurruti AA ChronologyChronology PaulPaul SharkeSharkeyy Zabalaza Books “Knowledge is the Key to be Free” Post: Postnet Suite 116, Private Bag X42, Braamfontein, 2017, Johannesburg, South Africa E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.zabalaza.net/zababooks Page 20 - The FoD: A Chronology debates began.’ At that group meeting the FoD explained what they understood the word ‘betrayal’ to signify and ‘...it was agreed that both parties would retract the terms they had used in the published note and manifesto.’ This was done in El Amigo del Pueblo, no. 3 (12 June 1937), but ‘...has yet to be done by those who unhesitatingly, unfairly and improperly endorsed our expulsion from the organisation for which we have sacrificed so much.’ In El Amigo del Pueblo, no. 4 (22 June 1937) Jaime Balius stated ‘In our last issue, we of the Friends of Durruti withdrew the charge of betrayal for the sake of anarchist revolutionary unity. And we hope that the committees will retract the charge of “agents provocateurs”.’ The FoD claims of grassroots support seem to be confirmed by Grandizo Munis, leader of the Spanish Bolshevik-Leninists, the Spanish Section of Trotsky’s Fourth International, who writes (Jalones de Derrota, Promesa de Victoria, Editorial Lucha Obrera Mexico, DF, 1948, The Friends of p. 290-291) ‘...the local committees refused to implement a resolution from the supe- rior committees expelling the chief (FoD) leaders.’ 4. Grandizo Munis (op. cit. p. 385) notes that ‘El Amigo del Pueblo, the organ of the “Friends of Durruti” and La Voz Leninista, the Trotskyists’ organ, easily distributed Durruti tens of thousands of copies and he adds ‘...even though anyone arrested with one of those papers in his pocket would have received a sentence of between 10 and 30 years’.