A Performance Guide to the Late Character Pieces for Piano By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romantic Listening Key

Name ______________________________ Romantic Listening Key Number: 7.1 CD 5/47 pg. 297 Title: Symphonie Fantastique, 4th mvmt Composer: Berlioz Genre: Program Symphony Characteristics Texture: ____________________________________________________ Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: timp start, high bsn solo Number: 7.2 CD 6/11 pg 339 Title: The Moldau Composer: Smetana Genre: symphonic poem Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: flute start Sections: two springs, the river, forest hunt, peasant wedding, moonlight dance of river nymphs, the river, the rapids, the river at its widest point, Vysehrad the ancient castle Name ______________________________ Number: 7.3 CD 5/51 pg 229 Title: Symphonie Fantastique, 5th mvmt (Dream of a Witch's Sabbath) Composer: Berlioz Genre: program symphony Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: funeral chimes, clarinet idee fix, trills & grace notes Number: 7.4 website Title: 1812 Overture Composer: Tchaikovsky Genre: concert overture Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: soft beginning, hunter motive, “Go Napoleon”, the battle Name ______________________________ Number: 7.5 website Title: The Sorcerer's Apprentice -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark D

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Summer 2017 College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music Mark D. Taylor James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Mark D., "College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music" (2017). Dissertations. 132. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark David Taylor A Doctor of Musical Arts Document submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music August 2017 FACULTY COMMITTEE Committee Chair: Dr. Eric Guinivan Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Mary Jean Speare Mr. Foster Beyers Acknowledgments Dr. Robert McCashin, former Director of Orchestras and Professor of Orchestral Conducting at James Madison University (JMU) as well as a co-founder of College Orchestra Directors Association (CODA), served as an important sounding-board as the study emerged. Dr. McCashin was particularly helpful in pointing out the challenges of undertaking such a study. I would have been delighted to have Dr. McCashin serve as the chair of my doctoral committee, but he retired from JMU before my study was completed. -

Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-7-2018 12:30 PM Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse Renee MacKenzie The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nolan, Catherine The University of Western Ontario Sylvestre, Stéphan The University of Western Ontario Kinton, Leslie The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Musical Arts © Renee MacKenzie 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation MacKenzie, Renee, "Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5572. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5572 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This monograph examines the post-exile, multi-version works of Sergei Rachmaninoff with a view to unravelling the sophisticated web of meanings and values attached to them. Compositional revision is an important and complex aspect of creating musical meaning. Considering revision offers an important perspective on the construction and circulation of meanings and discourses attending Rachmaninoff’s music. While Rachmaninoff achieved international recognition during the 1890s as a distinctively Russian musician, I argue that Rachmaninoff’s return to certain compositions through revision played a crucial role in the creation of a narrative and set of tropes representing “Russian diaspora” following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys. -

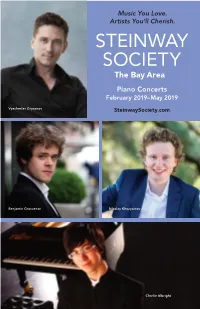

Steinway Society 2018-2019 Program

Music You Love. Artists You’ll Cherish. STEINWAY SOCIETY The Bay Area Piano Concerts February 2019–May 2019 Vyacheslav Gryaznov SteinwaySociety.com Benjamin Grosvenor Nikolay Khozyainov Charlie Albright PIANO CONCERTS 2018–2019 President’s Letter Dear Patron, Zlata Chochieva Saturday, September 15, 2018, 7:30 p.m. Steinway Society concerts continue this season with four Trianon Theatre, San Jose nationally and internationally acclaimed pianists. In this, our 24th year, we are honoring the Romantic era Manasse/Nakamatsu Duo (1825–1900), which saw the birth of the first celebrity Saturday, October 13, 2018, 7:30 p.m. pianists. While democratic ideals and the Industrial McAfee Performing Arts and Lecture Center, Saratoga Revolution changed the fabric of Western society, musicians were freed of dependence on the church and royal courts. Henry Kramer Musical forms were expanded to express “romanticism,” including artistic individualism and dramatic ranges of emotion. The spirit of Sunday, November 11, 2018, 2:30 p.m. romanticism infuses this 24th Steinway Society season. Trianon Theatre, San Jose The season continues with 21st-century Romantic pianist, Vyacheslav Sandra Wright Shen Gryaznov, who brings us gorgeous music of Rachmaninoff. Benjamin Grosvenor follows with music of Schumann, Janácek, and Prokofiev, Saturday, December 8, 2018, 7:30 p.m. who brought a new vision to romanticism. Nikolay Khozyainov treats Trianon Theatre, San Jose us to additional works of Chopin, Beethoven, and Rachmaninoff. Charlie Albright concludes the season by surveying romanticism’s variations, Kate Liu and by improvising, as did the great pianists of the Romantic era. Saturday, January 12, 2019, 7:30 p.m. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

21M011 (Spring, 2006) Ellen T. Harris Lecture VIII Romantic Era (Nineteenth Century) Literature: Gothic Novels (Mary Shelley, F

21M011 (spring, 2006) Ellen T. Harris Lecture VIII Romantic Era (Nineteenth Century) Literature: Gothic novels (Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, 1818), Grimm brothers Fairy Tales, Thoreau’s Walden, Dickens Poetry: Goethe, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, Keats, Byron, Whitman, Blake, Edgar Allan Poe Visual Arts: Constable, Turner, Cezanne, Rodin, Renoir, Monet, Seurat, Van Gogh Science, engineering and industrialization: Pasteur; McCormick’s mechanical reaper; Morse’s telegraph; Daguerre’s photographs; first electric light; ether used for first time as anesthetic (1846); Darwin Origin of Species (1859); first Atlantic cable (1864); first transcontinental railway in U.S. (1869); Suez Canal (1869); Bell’s telephone (1876); Edison’s phonograph; automobile patented by Daimler; Roentgen’s X-ray Exploration: Lewis and Clark reach the Pacific (1806); first steamship crosses the Atlantic (1818); Japan opened to the West (1853) Politics: 1804: Napoleon crowns self Emperor; 1805: Battle of Trafalgar; War of 1812 between England and U.S.; Napoleon invades Russia (1812); Battle of Waterloo (1815); Greek War of Independence (1822); July Revolution in France (1830); Polish revolt (1830); Revolutions in France, Prussia, Austria-Hungary and Italian states (1848); Marx and Engels, Communist Manifesto (1848); Italian risorgimento (1859-1861); Anti-slavery movement in U.S.; Abraham Lincoln, United States Civil War (1861-1865); Spanish- American War starts (1898) Kerman/Tomlinson provides a good introduction to this century (pp. 235-242). The following builds on that, emphasizing certain aspects. 1. The Romantic Era is closely tied to literature; the very name comes from the literary world, whose authors themselves adopted the name “Romantics.” For music, the close tie with literature is a dominant feature of the period. -

JEREMY DENK, Piano Considered Normal in the Late 19Th Century, the Piano Pieces of Op

Four Piano Pieces, Op. 119 [1893] pieces, a vast panorama of moods that opens heroically with a JOHANNES BRAHMS muscular march, emphatic and forthright in rhythm but irregularly Born May 7, 1833, in Hamburg, Germany structured in ‘Hungarian-style’ 5-bar phrases. Its middle section Died April 3, 1897, in Vienna, Austria alternates between pulsing triplet gures in a worrisome C Minor and the cane-twirling, walk-in-the-park breeziness of a debonaire rahms’s last works for the piano were a set of Four Keyboard A flat major section in the classic style of late-19th-century salon Pieces, Op.119. Like the previous short piano pieces of Opp. music. A flamboyant gypsy-style coda ends the piece, surprisingly, 116, 117, and 118, they are complex, dense, and deeply with a triumphant cadence in E flat minor. Thursday • November 12 • 7:00 pm B Benjamin Franklin Hall introspective works, full of rhythmic and harmonic ambiguities © 2020 by Bernard Jacobson but by no means obscure. They are works to be savoured for American Philosophical Society Brahms’s mastery of compositional technique and for the bountiful This recital is part of the Elaine Kligerman Piano Series wellspring of Viennese sentiment and charm that animates them from within. JEREMY DENK Written with complete disregard for the kinds of piano textures eremy Denk is one of America’s foremost pianists. Winner of a JEREMY DENK, piano considered normal in the late 19th century, the piano pieces of Op. MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship and the Avery Fisher Prize, Denk was recently elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. -

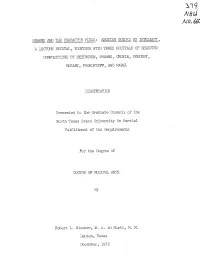

Brahms and the Character Piece: Emotion Guided by Intellect

A/Sf BRAHMS AND THE CHARACTER PIECE: EMOTION GUIDED BY INTELLECT, A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED COMPOSITIONS BY BEETHOVEN, BRAHMS, CHOPIN, DEBUSSY, MOZART, PROKOFIEFF, AND RAVEL DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By Robert L. Blocker, B. A. in Music, M. M. Denton, Texas December, 1972 Blocker, Robert L., Brahms and the Character Piece: Emotion Guided by_ Intellect., A Lecture Recital, Together With Three Recitals of Selected Compositions by_ Beethoven, Brahms, Chpin, Debussy, Mozart, Prokofieff, and Ravel. Doctor of Musical Arts (Piano Performance), December, 1972, 21 pp., illustrations, bibliography, 31 titles. The lecture recital was given October 15, 1971. The subject of the discussion was Brahms and the Character Piece: Emotion Guided by Intellect, and it included historical and biographical information, an analysis of Brahms' romantic-classic style, a general analysis of the six character pieces in Opus 118, and performance of Opus 118 by memory. In addition to the lecture recital, three other public recitals were performed. These three programs were comprised of solo litera- ture for the piano. The first solo recital was on April 15, 1971, and included works of Brahms, Chopin, Mozart, and Ravel. The second program, presented on April 28, 1972, featured several works of Beethoven. Performed on Septemhber 25, 1972, the third recital programmed compositions by Chopin, Debussy, and Prokofieff. Magnetic tape recordings of all four programs and the written lecture material are filed together as the dissertation. Tape recordings of all performances submitted as dissertation are on deposit in the North Texas State University Library. -

Formal and Harmonic Considerations in Clara Schumann's Drei Romanzen, Op. 21, No. 1

FORMAL AND HARMONIC CONSIDERATIONS IN CLARA SCHUMANN'S DREI ROMANZEN, OP. 21, NO. 1 Katie Lakner A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2015 Committee: Gregory Decker, Advisor Gene Trantham © 2015 Katie Lakner All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Gregory Decker, Advisor As one of her most mature works, Clara Schumann’s Drei Romanzen, op. 21, no. 1, composed in 1855, simultaneously encapsulates her musical preferences after half a lifetime of extensive musical study and reflects the strictures applied to “women’s music” at the time. During the Common Practice Period, music critics would deride music by women that sounded too “masculine” or at least not “feminine” enough. Women could not write more progressive music without risking a backlash from the music critics. However, Schumann’s music also had to earn the respect of her more progressive fellow composers. In this piece, she achieved that balance by employing a very Classical formal structure and a distinctly Romantic, if somewhat restrained, harmonic language. Her true artistic and compositional talents shine forth despite, and perhaps even due to, the limits in which her music had to reside. iv Dedicated to Dennis and Janet Lakner. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks the Gregory Decker and Gene Trantham for their incredible patience and guidance throughout the writing of this paper. Thanks to Dennis and Janet Lakner and Debra Unterreiner for their constant encouragement and mental and emotional support. Finally, special thanks to the baristas at the Barnes and Noble café in Fenton, MO, for providing the copious amounts of caffeine necessary for the completion of this paper.