MTO 19.4: Wennerstrom, Review of Bribitzer-Stull

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romantic Listening Key

Name ______________________________ Romantic Listening Key Number: 7.1 CD 5/47 pg. 297 Title: Symphonie Fantastique, 4th mvmt Composer: Berlioz Genre: Program Symphony Characteristics Texture: ____________________________________________________ Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: timp start, high bsn solo Number: 7.2 CD 6/11 pg 339 Title: The Moldau Composer: Smetana Genre: symphonic poem Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: flute start Sections: two springs, the river, forest hunt, peasant wedding, moonlight dance of river nymphs, the river, the rapids, the river at its widest point, Vysehrad the ancient castle Name ______________________________ Number: 7.3 CD 5/51 pg 229 Title: Symphonie Fantastique, 5th mvmt (Dream of a Witch's Sabbath) Composer: Berlioz Genre: program symphony Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: funeral chimes, clarinet idee fix, trills & grace notes Number: 7.4 website Title: 1812 Overture Composer: Tchaikovsky Genre: concert overture Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: soft beginning, hunter motive, “Go Napoleon”, the battle Name ______________________________ Number: 7.5 website Title: The Sorcerer's Apprentice -

The Meshuggah Quartet

The Meshuggah Quartet Applying Meshuggah's composition techniques to a quartet. Charley Rose jazz saxophone, MA Conservatorium van Amsterdam, 2013 Advisor: Derek Johnson Research coordinator: Walter van de Leur NON-PLAGIARISM STATEMENT I declare 1. that I understand that plagiarism refers to representing somebody else’s words or ideas as one’s own; 2. that apart from properly referenced quotations, the enclosed text and transcriptions are fully my own work and contain no plagiarism; 3. that I have used no other sources or resources than those clearly referenced in my text; 4. that I have not submitted my text previously for any other degree or course. Name: Rose Charley Place: Amsterdam Date: 25/02/2013 Signature: Acknowledgment I would like to thank Derek Johnson for his enriching lessons and all the incredibly precise material he provided to help this project forward. I would like to thank Matis Cudars, Pat Cleaver and Andris Buikis for their talent, their patience and enthusiasm throughout the elaboration of the quartet. Of course I would like to thank the family and particularly my mother and the group of the “Four” for their support. And last but not least, Iwould like to thank Walter van de Leur and the Conservatorium van Amsterdam for accepting this project as a master research and Open Office, open source productivity software suite available on line at http://www.openoffice.org/, with which has been conceived this research. Introduction . 1 1 Objectives and methodology . .2 2 Analysis of the transcriptions . .3 2.1 Complete analysis of Stengah . .3 2.1.1 Riffs . -

Class Piano Handbook

CLASS PIANO HANDBOOK THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, KNOXVILLE COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES SCHOOL OF MUSIC DR. EUNSUK JUNG LECTURER OF PIANO COORDINATOR OF CLASS PIANO TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION 3 CONTACT INFORMATION 4 COURSE OBJECTIVES CLASS PIANO I & II 5 CLASS PIANO III & IV 6 ACTIVITIES AND SKILLS INCLUDED IN CLASS PIANO 7 PIANO LAB POLICIES 8 GUIDELINES FOR EFFECTIVE PRACTICE 9 TESTING OUT OF CLASS PIANO 11 KEYBOARD PROFICIENCY TEST REQUIREMENTS CLASS PIANO I (MUKB 110) 12 CLASS PIANO II (MUKB 120) 13 CLASS PIANO III (MUKB 210) 14 CLASS PIANO IV (MUKB 220) 15 FAQs 16 UTK CLASS PIANO HANDBOOK | 2 GENERAL INFORMATION Class Piano is a four-semester course program designed to help undergraduate non- keyboard music majors to develop the following functional skills for keyboard: technique (scales, arpeggios, & chord progressions), sight-reading, harmonization, transposition, improvisation, solo & ensemble playing, accompaniment, and score reading (choral & instrumental). UTK offers four levels of Class Piano in eight different sections. Each class meets twice a week for 50 minutes and is worth one credit hour. REQUIRED COURSES FOR MAJORS Music Education with Instrumental MUKB 110 & 120 Emphasis (Class Piano I & II) Music Performance, Theory/Composition, MUKB 110, 120, 210, & 220 Music Education with Vocal Emphasis (Class Piano I, II, III, & IV) CLASS PIANO PROFICIENCY EXAM Proficiency in Keyboard skills is usually acquired in the four-semester series of Class Piano (MUKB 110, 120, 210, & 220). To receive credit for Class Piano, students must register for, take, and pass each class. Students who are enrolled in Class Piano will be prepared to meet the proficiency requirement throughout the course of study. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark D

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Summer 2017 College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music Mark D. Taylor James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Mark D., "College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music" (2017). Dissertations. 132. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark David Taylor A Doctor of Musical Arts Document submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music August 2017 FACULTY COMMITTEE Committee Chair: Dr. Eric Guinivan Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Mary Jean Speare Mr. Foster Beyers Acknowledgments Dr. Robert McCashin, former Director of Orchestras and Professor of Orchestral Conducting at James Madison University (JMU) as well as a co-founder of College Orchestra Directors Association (CODA), served as an important sounding-board as the study emerged. Dr. McCashin was particularly helpful in pointing out the challenges of undertaking such a study. I would have been delighted to have Dr. McCashin serve as the chair of my doctoral committee, but he retired from JMU before my study was completed. -

Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-7-2018 12:30 PM Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse Renee MacKenzie The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nolan, Catherine The University of Western Ontario Sylvestre, Stéphan The University of Western Ontario Kinton, Leslie The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Musical Arts © Renee MacKenzie 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation MacKenzie, Renee, "Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5572. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5572 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This monograph examines the post-exile, multi-version works of Sergei Rachmaninoff with a view to unravelling the sophisticated web of meanings and values attached to them. Compositional revision is an important and complex aspect of creating musical meaning. Considering revision offers an important perspective on the construction and circulation of meanings and discourses attending Rachmaninoff’s music. While Rachmaninoff achieved international recognition during the 1890s as a distinctively Russian musician, I argue that Rachmaninoff’s return to certain compositions through revision played a crucial role in the creation of a narrative and set of tropes representing “Russian diaspora” following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. -

Guitar/Keyboard/Harmonizing Instruments Harmonizing a Melody Proficient for Creating

Guitar/Keyboard/Harmonizing Instruments Harmonizing a Melody Proficient for Creating Intent of the Model Cornerstone Assessments Description of the MCA Model Cornerstone Assessments (MCAs) in music assessment Students will harmonize a recorded frameworks to be used by music teachers within their school’s major (do-based) pentatonic folk curriculum to measure student attainment of process song by analyzing the melody components defined by performance standards in the National aurally and from written notation. Core Music Standards. They focus on one or more Artistic Using previously learned chords, Process (i.e., Creating, Performing, or Responding) and students will individually plan a designed as a series of curriculum-embedded assessment tasks, harmonic accompaniment that each of which measures students’ ability to carry out one or best fits the melody, notate their more process components. The MCAs can be used as formative harmonization using an analysis and summative indications of learning, but do not indicate system (e.g., chord letter names, quality of teaching or effectiveness of a school’s music program. functional harmony), and rhythmic accompanying patterns (e.g. Although each MCA is designed so that it can be administered strumming patterns, block chords, within an instructional sequence or unit, teachers may choose and arpeggios). Finally, students to spread the component parts of one MCA across multiple will present their harmonization to units or projects. Student work produced by the national pilot is a peer or group of peers, and available on the NAfME website that illustrates the level of thoughtfully respond to a achievement envisioned in the National Core Music Standards. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

Guidance for Measure Harmonization

Measure Harmonization Guidance for Measure Harmonization A CONSENSUS REPORT National Quality Forum The National Quality Forum (NQF) operates under a three-part mission to improve the quality of American healthcare by: • building consensus on national priorities and goals for performance improvement and working in partnership to achieve them; • endorsing national consensus standards for measuring and publicly reporting on performance; and • promoting the attainment of national goals through education and outreach programs. This project is funded under NQF’s contract with the Department of Health and Human Services, Consensus-based Entities Regarding Healthcare Performance Measurement. Recommended Citation: National Quality Forum (NQF), Guidance for Measure Harmonization: A Consensus Report, Washington, DC: NQF; 2010. © 2010. National Quality Forum All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-9828421-4-0 No part of this report may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the National Quality Forum. Requests for permission to reprint or make copies should be directed to: Permissions National Quality Forum 601 13th Street NW Suite 500 North Washington, DC 20005 Fax 202-783-3434 www.qualityforum.org Guidance for Measure Harmonization: A Consensus Report Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 Purpose ............................................................................................................. -

Graduate Music Theory Exam Preparation Guidelines

Graduate Theory Entrance Exam Information and Practice Materials 2016 Summer Update Purpose The AU Graduate Theory Entrance Exam assesses student mastery of the undergraduate core curriculum in theory. The purpose of the exam is to ensure that incoming graduate students are well prepared for advanced studies in theory. If students do not take and pass all portions of the exam with a 70% or higher, they must satisfactorily complete remedial coursework before enrolling in any graduate-level theory class. Scheduling The exam is typically held 8:00 a.m.-12:00 p.m. on the Thursday just prior to the start of fall semester classes. Check with the Music Department Office for confirmation of exact dates/times. Exam format The written exam will begin at 8:00 with aural skills (intervals, sonorities, melodic and harmonic dictation) You will have until 10:30 to complete the remainder of the written exam (including four- part realization, harmonization, analysis, etc.) You will sign up for individual sight-singing tests, to begin directly after the written exam Activities and Skills Aural identification of intervals and sonorities Dictation and sight-singing of tonal melodies (both diatonic and chromatic). Notate both pitch and rhythm. Dictation of tonal harmonic progressions (both diatonic and chromatic). Notate soprano, bass, and roman numerals. Multiple choice Short answer Realization of a figured bass (four-part voice leading) Harmonization of a given melody (four-part voice leading) Harmonic analysis using roman numerals 1 Content -

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys. -

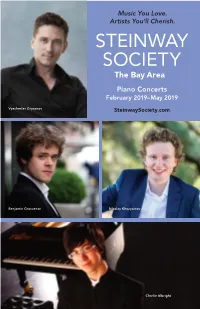

Steinway Society 2018-2019 Program

Music You Love. Artists You’ll Cherish. STEINWAY SOCIETY The Bay Area Piano Concerts February 2019–May 2019 Vyacheslav Gryaznov SteinwaySociety.com Benjamin Grosvenor Nikolay Khozyainov Charlie Albright PIANO CONCERTS 2018–2019 President’s Letter Dear Patron, Zlata Chochieva Saturday, September 15, 2018, 7:30 p.m. Steinway Society concerts continue this season with four Trianon Theatre, San Jose nationally and internationally acclaimed pianists. In this, our 24th year, we are honoring the Romantic era Manasse/Nakamatsu Duo (1825–1900), which saw the birth of the first celebrity Saturday, October 13, 2018, 7:30 p.m. pianists. While democratic ideals and the Industrial McAfee Performing Arts and Lecture Center, Saratoga Revolution changed the fabric of Western society, musicians were freed of dependence on the church and royal courts. Henry Kramer Musical forms were expanded to express “romanticism,” including artistic individualism and dramatic ranges of emotion. The spirit of Sunday, November 11, 2018, 2:30 p.m. romanticism infuses this 24th Steinway Society season. Trianon Theatre, San Jose The season continues with 21st-century Romantic pianist, Vyacheslav Sandra Wright Shen Gryaznov, who brings us gorgeous music of Rachmaninoff. Benjamin Grosvenor follows with music of Schumann, Janácek, and Prokofiev, Saturday, December 8, 2018, 7:30 p.m. who brought a new vision to romanticism. Nikolay Khozyainov treats Trianon Theatre, San Jose us to additional works of Chopin, Beethoven, and Rachmaninoff. Charlie Albright concludes the season by surveying romanticism’s variations, Kate Liu and by improvising, as did the great pianists of the Romantic era. Saturday, January 12, 2019, 7:30 p.m.