Pest Risk Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduced Population of Ring-Necked Parakeets Psittacula Krameri in Madeira Island, Portugal – Call for Early Action

Management of Biological Invasions (2020) Volume 11, Issue 3: 576–587 CORRECTED PROOF Research Article Introduced population of ring-necked parakeets Psittacula krameri in Madeira Island, Portugal – Call for early action Ricardo Rocha1,2, Luís Reino1,2, Pedro Sepúlveda3 and Joana Ribeiro1,2,* 1Laboratório Associado, CIBIO/InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Campus Agrário de Vairão, 4485-661 Vairão, Portugal 2Laboratório Associado, CIBIO/InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Tapada da Ajuda, 1349-017 Lisbon, Portugal 3DROTA - Direção Regional do Ordenamento do Território e Ambiente, Rua Dr. Pestana Júnior, 9064-506 Funchal, Portugal Author e-mails: [email protected] (RR), [email protected] (LR), [email protected] (PS), [email protected], [email protected] (JR) *Corresponding author Citation: Rocha R, Reino L, Sepúlveda P, Ribeiro J (2020) Introduced population of Abstract ring-necked parakeets Psittacula krameri in Madeira Island, Portugal – Call for early Alien invasive species are major drivers of ecological change worldwide, being action. Management of Biological especially detrimental in oceanic islands, where they constitute one of the greatest Invasions 11(3): 576–587, https://doi.org/10. threats to the survival of native species. Ring-necked parakeets Psittacula krameri 3391/mbi.2020.11.3.15 (Scopoli, 1769) are popular pets and individuals escaped from captivity have formed Received: 29 October 2019 multiple self-sustainable populations outside their native range. For over ten years, Accepted: 5 March 2020 free-ranging ring-necked parakeets have regularly been observed in Madeira Island Published: 28 May 2020 (Portugal) and strong evidence suggests that they have breed multiple times in Funchal, the capital of the island. -

§4-71-6.5 LIST of CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November

§4-71-6.5 LIST OF CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November 28, 2006 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Plesiopora FAMILY Tubificidae Tubifex (all species in genus) worm, tubifex PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Crustacea ORDER Anostraca FAMILY Artemiidae Artemia (all species in genus) shrimp, brine ORDER Cladocera FAMILY Daphnidae Daphnia (all species in genus) flea, water ORDER Decapoda FAMILY Atelecyclidae Erimacrus isenbeckii crab, horsehair FAMILY Cancridae Cancer antennarius crab, California rock Cancer anthonyi crab, yellowstone Cancer borealis crab, Jonah Cancer magister crab, dungeness Cancer productus crab, rock (red) FAMILY Geryonidae Geryon affinis crab, golden FAMILY Lithodidae Paralithodes camtschatica crab, Alaskan king FAMILY Majidae Chionocetes bairdi crab, snow Chionocetes opilio crab, snow 1 CONDITIONAL ANIMAL LIST §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Chionocetes tanneri crab, snow FAMILY Nephropidae Homarus (all species in genus) lobster, true FAMILY Palaemonidae Macrobrachium lar shrimp, freshwater Macrobrachium rosenbergi prawn, giant long-legged FAMILY Palinuridae Jasus (all species in genus) crayfish, saltwater; lobster Panulirus argus lobster, Atlantic spiny Panulirus longipes femoristriga crayfish, saltwater Panulirus pencillatus lobster, spiny FAMILY Portunidae Callinectes sapidus crab, blue Scylla serrata crab, Samoan; serrate, swimming FAMILY Raninidae Ranina ranina crab, spanner; red frog, Hawaiian CLASS Insecta ORDER Coleoptera FAMILY Tenebrionidae Tenebrio molitor mealworm, -

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

Rødbrystet Conure

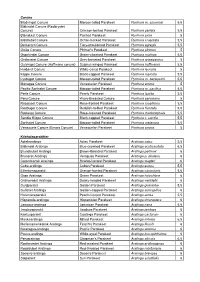

Conure Blodvinget Conure Maroon -tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. souancei 5,5 Blåkindet Conure (Rødbrystet Conure) Crimson-bellied Parakeet Pyrrhura perlata 5,5 Blånakket Conure Painted Parakeet Pyrrhura picta 5 Blåstrubet Conure Ochre-marked Parakeet Pyrrhura cruentata 5,5 Demerara Conure Fiery-shouldered Parakeet Pyrrhura egregia 5,5 Goiás Conure Pfrimer's Parakeet Pyrrhura pfrimeri 5 Grønkindet Conure Green-cheeked Parakeet Pyrrhura molinae 5,5 Gråbrystet Conure Grey-breasted Parakeet Pyrrhura griseipectus 5 Gulvinget Conure (Hoffmans conure) Sulphur-winged Parakeet Pyrrhura hoffmanni 5,5 Hvidøret Conure White-eared Parakeet Pyrrhura leucotis 5 Klippe Conure Black-capped Parakeet Pyrrhura rupicola 5,5 Lysbuget Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. berlepschi 5,5 Monagas Conure Venezuelan Parakeet Pyrrhura emma 5 Pacific Sorthalet Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. pacifica 5,5 Perle Conure Pearly Parakeet Pyrrhura lepida 5,5 Peru Conure Wavy-Breasted Conure Pyrrhura peruviana 5 Rosaisset Conure Rose-fronted Parakeet Pyrrhura roseifrons 5,5 Rødbuget Conure Reddish-bellied Parakeet Pyrrhura frontalis 5,5 Rødisset Conure Rose-crowned Parakeet Pyrrhura rhodocephala 5,5 Sandia Klippe Conure Black-capped Parakeet Pyrrhura r. sandia 5,5 Sorthalet Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura melanura 5,5 Venezuela Conure (Emma Conure) Venezuelan Parakeet Pyrrhura emma 5 Kilehaleparakitter Aztekaratinga Aztec Parakeet Aratinga astec 5,5 Blåkindet Aratinga Blue-crowned Parakeet Aratinga acuticaudata 6,5 Brunstrubet Aratinga Brown-throated Parakeet -

Vogelliste Venezuela

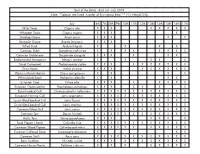

Vogelliste Venezuela Datum: www.casa-vieja-merida.com (c) Beobachtungstage: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Birdlist VENEZUELA copyrightBeobachtungsgebiete: Henri Pittier Azulita / Catatumbo La Altamira St Domingo Paramo Los Llanos Caura Sierra de Imataca Sierra de Lema + Gran Sabana Sucre Berge und Kueste Transfers Andere - gesehen gesehen an wieviel Tagen TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae - Steißhühner 0 1 Tawny-breasted Tinamou Nothocercus julius Gelbbrusttinamu 0 2 Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei Bergtinamu 0 3 Gray Tinamou Tinamus tao Tao 0 4 Great Tinamou Tinamus major Großtinamu x 0 5 White-throated Tinamou Tinamus guttatus Weißkehltinamu 0 6 Cinereous Tinamou Crypturellus cinereus Grautinamu x x 0 7 Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui Brauntinamu x x x 0 8 Tepui Tinamou Crypturellus ptaritepui Tepuitinamu by 0 9 Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus Kastanientinamu 0 10 Undulated Tinamou Crypturellus undulatus Wellentinamu 0 11 Gray-legged Tinamou Crypturellus duidae Graufußtinamu 0 12 Red-legged Tinamou Crypturellus erythropus Rotfußtinamu birds-venezuela.dex x 0 13 Variegated Tinamou Crypturellus variegatus Rotbrusttinamu x x x 0 14 Barred Tinamou Crypturellus casiquiare Bindentinamu 0 ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae - Entenvögel 0 15 Horned Screamer Anhima cornuta Hornwehrvogel x 0 16 Northern Screamer Chauna chavaria Weißwangen-Wehrvogel x 0 17 White-faced Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna viduata Witwenpfeifgans x 0 18 Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Rotschnabel-Pfeifgans x 0 19 Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Psittacula Krameri) and Alexandrine Parakeets (Psittacula Eupatria) in Istanbul’S City Parks

Şahin – Arslangündoğdu: Breeding status and nest characteristics of Rose-ringed and Alexandrine parakeets in Istanbul - 2461 - BREEDING STATUS AND NEST CHARACTERISTICS OF ROSE- RINGED (PSITTACULA KRAMERI) AND ALEXANDRINE PARAKEETS (PSITTACULA EUPATRIA) IN ISTANBUL’S CITY PARKS ŞAHIN, D.1 – ARSLANGÜNDOĞDU, Z.2* 1Boğaziçi University Institute of Environmental Sciences, Istanbul, Turkey 2Department of Forest Entomology and Protection, Faculty of Forestry, Istanbul University- Cerrahpaşa, Istanbul, Turkey *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]; phone:+90-212-338-2400/ext. 25256; fax: +90-212-338-2424 (Received 25th Oct 2018; accepted 28th Jan 2019) Abstract. Invasive non-native parakeet populations are increasing throughout Europe with proved negative impact on native fauna and Turkey is no exception. Rose-ringed and Alexandrine parakeets have established populations in Turkey’s large cities but even basic distribution, abundance and breeding behaviour information is missing. This study aims at determining the breeding status and identifying the nest characteristics of Rose-ringed and Alexandrine parakeets in Istanbul’s city parks. The study is carried out in 9 city parks during one breeding season. Data on the presence of breeding parakeet species, their nest characteristics and characteristic of suitable cavities on non-nesting trees were collected. Both species were recorded breeding sympatrically in 5 out of 9 city parks with probable breeding in one more park. When nesting, both species preferred high trees with high diameter but Rose-ringed parakeet nests were placed lower than those of Alexandrine parakeet’s. Plane (Platanus sp.) species were the most used as a nesting tree for both species. This study reveals the first systematic observations on the breeding Rose-ringed and Alexandrine parakeet populations in Istanbul and serves as a basis for further detailed research on both species in Turkey. -

Parrots in the London Area a London Bird Atlas Supplement

Parrots in the London Area A London Bird Atlas Supplement Richard Arnold, Ian Woodward, Neil Smith 2 3 Abstract species have been recorded (EASIN http://alien.jrc. Senegal Parrot and Blue-fronted Amazon remain between 2006 and 2015 (LBR). There are several ec.europa.eu/SpeciesMapper ). The populations of more or less readily available to buy from breeders, potential factors which may combine to explain the Parrots are widely introduced outside their native these birds are very often associated with towns while the smaller species can easily be bought in a lack of correlation. These may include (i) varying range, with non-native populations of several and cities (Lever, 2005; Butler, 2005). In Britain, pet shop. inclination or ability (identification skills) to report species occurring in Europe, including the UK. As there is just one parrot species, the Ring-necked (or Although deliberate release and further import of particular species by both communities; (ii) varying well as the well-established population of Ring- Rose-ringed) parakeet Psittacula krameri, which wild birds are both illegal, the captive populations lengths of time that different species survive after necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri), five or six is listed by the British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU) remain a potential source for feral populations. escaping/being released; (iii) the ease of re-capture; other species have bred in Britain and one of these, as a self-sustaining introduced species (Category Escapes or releases of several species are clearly a (iv) the low likelihood that deliberate releases will the Monk Parakeet, (Myiopsitta monachus) can form C). The other five or six¹ species which have bred regular event. -

Recent Literature [17 5

v 1940 Recent Literature [17 5 RECENT LITERATURE Reviews by Margaret M. Nice BANDING AND MIGRATION 1. Results from the First Ten Years of Banding Belgian Birds in the Nest. (R•sultats du Baguage au Nid des Oiseaux de Belgique pour les Dix PremieresAnn•es (1928-1938).) R. Verheyen. 1939. Bull. du Music royal d' Histoire nat. de Belgique,15 (49): 1-36.--A valuablepiece of work. As a rule nestlingsare found to return to the region of their birth, within 5, 10, 15 or 25 kilometersaccording to species. There were 447 casesof suchreturn and only a few exceptions(notably with the Cormorant (Phalacrocoraxcarbo) ), while a Sparrow Hawk (Accipiter nisus) settled 62 kilometersfrom its birthplace and a Kestrel (Falco tinnunculus)130. Of 5 species132-228 birds were retaken, of 5 othersfrom 51-82, and of 6 othersfro TM 25-44. In 15 of thesethe mortality during the first two yearsranged between 76 and 92 per cent,(with the Jackdaw (Coleusmonedula) it was 44 per cent), the averageof all being82 per cent. A large number of speciesare found to be only partially migratory: Sparrow Hawk, Stock Dove (Co!umbaoenas), Skylark (Alauda arvensis),Mistle Thrush ( Turdusviscivorus), Redl•reast (Erithacus rubecula), Greenfinch (Chloris chloris), Chaffinch(Fringilla coelebs),Great Tit (Parus major), Pied Wagtail (Motacilla alba,),and Starling (Sturnusvulgaris). Data are given on longevity. Mention is made of a BlackheadedGull ( Larus ridibundus)taken in Labrador in September 1933. The total numberof youngbanded in the nest is not given. It would be of great interest to have a similar study of returns and recoveriesof nestlings bandedin this country. -

An Update of Wallacels Zoogeographic Regions of the World

REPORTS To examine the temporal profile of ChC produc- specification of a distinct, and probably the last, 3. G. A. Ascoli et al., Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 557 (2008). tion and their correlation to laminar deployment, cohort in this lineage—the ChCs. 4. J. Szentágothai, M. A. Arbib, Neurosci. Res. Program Bull. 12, 305 (1974). we injected a single pulse of BrdU into pregnant A recent study demonstrated that progeni- CreER 5. P. Somogyi, Brain Res. 136, 345 (1977). Nkx2.1 ;Ai9 females at successive days be- tors below the ventral wall of the lateral ventricle 6. L. Sussel, O. Marin, S. Kimura, J. L. Rubenstein, tween E15 and P1 to label mitotic progenitors, (i.e., VGZ) of human infants give rise to a medial Development 126, 3359 (1999). each paired with a pulse of tamoxifen at E17 to migratory stream destined to the ventral mPFC 7. S. J. Butt et al., Neuron 59, 722 (2008). + 18 8. H. Taniguchi et al., Neuron 71, 995 (2011). label NKX2.1 cells (Fig. 3A). We first quanti- ( ). Despite species differences in the develop- 9. L. Madisen et al., Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133 (2010). fied the fraction of L2 ChCs (identified by mor- mental timing of corticogenesis, this study and 10. J. Szabadics et al., Science 311, 233 (2006). + phology) in mPFC that were also BrdU+. Although our findings raise the possibility that the NKX2.1 11. A. Woodruff, Q. Xu, S. A. Anderson, R. Yuste, Front. there was ChC production by E15, consistent progenitors in VGZ and their extended neurogenesis Neural Circuits 3, 15 (2009). -

A Risk Assessment of Mandarin Duck (Aix Galericulata) in the Netherlands

van Kleunen A. & Lemaire A.J.J. A. & Lemaire van Kleunen van Kleunen A. & Lemaire A.J.J. A. & Lemaire van Kleunen A risk assessment of Mandarin Duck in the Netherlands A A risk assessment of Mandarin Duck in the Netherlands A A risk assessment of Mandarin Duck (Aix galericulata) in the André van Kleunen & Adrienne Lemaire Netherlands Sovon-report 2014/15 Sovon Dutch Centre for Field Ornithology Sovon-report 2014/15 Postbus 6521 Sovon 6503 GA Nijmegen Toernooiveld 1 -report 2014/15 6525 ED Nijmegen T (024) 7 410 410 E [email protected] I www.sovon.nl A risk assessment of Mandarin Duck in the Netherlands A risk assessment of Mandarin Duck (Aix galericulata) in the Netherlands A. van Kleunen & A.J.J. Lemaire Sovon-report 2014/15 This document was commissioned by: Office for Risk Assessment and Research Team invasive alien species Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (NVWA) Ministry of Economic Affairs Sovon/report 2014-15 Colophon © 2014 Sovon Dutch Centre for Field Ornithology Recommended citation: van Kleunen A. & Lemaire A.J.J. 2014. A risk assessment of Mandarin Duck (Aix Galericulata) in the Netherlands. Sovon-report 2014/15. Sovon Dutch Centre for Field Ornithology, Nijmegen. Lay out: John van Betteray Foto’s: Frank Majoor, Marianne Slot, Ana Verburen & Roy Verhoef Sovon Vogelonderzoek Nederland (Sovon Dutch Centre for Field Ornithology) Toernooiveld 1 6525 ED Nijmegen e-mail: [email protected] website: www.sovon.nl ISSN: 2212-5027 Nothing of this report may be multiplied or published by means of print, photocopy, microfilm or any other means without written consent by Sovon and/or the commissioning party. -

Revising the Phylogenetic Position of the Extinct Mascarene Parrot

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 107 (2017) 499–502 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Short Communication Revising the phylogenetic position of the extinct Mascarene Parrot Mascarinus mascarin (Linnaeus 1771) (Aves: Psittaciformes: Psittacidae) ⇑ Lars Podsiadlowski a, , Anita Gamauf b,c, Till Töpfer d a Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Zooecology, Bonn, Germany b Museum of Natural History Vienna, 1st Zoological Department – Ornithology, Burgring 7, 1010 Vienna, Austria c University of Vienna, Dept. Integrative Zoology, Althanstr. 14, A-1090 Vienna, Austria d Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Section Ornithology, Adenauerallee 160, Bonn, Germany article info abstract Article history: The phylogenetic position of the extinct Mascarene Parrot Mascarinus mascarin from La Réunion has been Received 4 August 2016 unresolved for centuries. A recent molecular study unexpectedly placed M. mascarin within the clade of Revised 25 November 2016 phenotypically very different Vasa parrots Coracopsis. Based on DNA extracted from the only other pre- Accepted 20 December 2016 served Mascarinus specimen, we show that the previously obtained cytb sequence is probably an artificial Available online 22 December 2016 composite of partial sequences from two other parrot species and that M. mascarin is indeed a part of the Psittacula diversification, placed close to P. eupatria and P. wardi. Keywords: Ó 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Mascarinus Mascarin Coracopsis Psittacula Extinction Indian Ocean parrots 1. Introduction stated explicitly by Peterson (2013) and Dickinson and Remsen (2013) and applied by del Hoyo and Collar (2014). For taxonomic The Mascarene Parrot or Mascarin, Mascarinus mascarin names above the species level we follow the system proposed by (Linnaeus, 1771), was one of a series of bird species from the Mas- Joseph et al.