Recent Literature [17 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

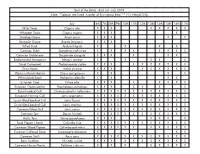

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

A Risk Assessment of Mandarin Duck (Aix Galericulata) in the Netherlands

van Kleunen A. & Lemaire A.J.J. A. & Lemaire van Kleunen van Kleunen A. & Lemaire A.J.J. A. & Lemaire van Kleunen A risk assessment of Mandarin Duck in the Netherlands A A risk assessment of Mandarin Duck in the Netherlands A A risk assessment of Mandarin Duck (Aix galericulata) in the André van Kleunen & Adrienne Lemaire Netherlands Sovon-report 2014/15 Sovon Dutch Centre for Field Ornithology Sovon-report 2014/15 Postbus 6521 Sovon 6503 GA Nijmegen Toernooiveld 1 -report 2014/15 6525 ED Nijmegen T (024) 7 410 410 E [email protected] I www.sovon.nl A risk assessment of Mandarin Duck in the Netherlands A risk assessment of Mandarin Duck (Aix galericulata) in the Netherlands A. van Kleunen & A.J.J. Lemaire Sovon-report 2014/15 This document was commissioned by: Office for Risk Assessment and Research Team invasive alien species Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (NVWA) Ministry of Economic Affairs Sovon/report 2014-15 Colophon © 2014 Sovon Dutch Centre for Field Ornithology Recommended citation: van Kleunen A. & Lemaire A.J.J. 2014. A risk assessment of Mandarin Duck (Aix Galericulata) in the Netherlands. Sovon-report 2014/15. Sovon Dutch Centre for Field Ornithology, Nijmegen. Lay out: John van Betteray Foto’s: Frank Majoor, Marianne Slot, Ana Verburen & Roy Verhoef Sovon Vogelonderzoek Nederland (Sovon Dutch Centre for Field Ornithology) Toernooiveld 1 6525 ED Nijmegen e-mail: [email protected] website: www.sovon.nl ISSN: 2212-5027 Nothing of this report may be multiplied or published by means of print, photocopy, microfilm or any other means without written consent by Sovon and/or the commissioning party. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

NEWSLETTER Ile

ISSN 0144-5 88x NEWSLETTER ile. ·~ Volume3 Part 9 1984 Biology Curators' Group L .d. •. CONTENTS BCG Newsletter vol.3 no.9 Editorial 487 Errata 487 Letters 438 Local Records Centres and Environmental Recording Where do we go from here 7 (C.J.T.Copp) ••• 489 The Need of Local Authorities for Environmental . ·~ Information (K.Francis) .... 498 Biological Site Recording at Sheffield Museum (S.P.Garland & D.Whiteley) . 504 Herbarium of Sir~. Benjamin Stone (B.Abell Seddon) 517 Sources of Biological Records "The Naturalist" Part 3 (W.A.Ely) 519 Society for the History of Natural History 530 Plant Galls Bulletin 530 The Duties of Natural History (P.Lingwood) 531 Publicity for Museum Insect Collections (S.Judd) 534 Help for Flora Compiling (BSBI) 534 Book News and Reviews 535 AGM - Report of the inquorate AGM held at Brighton on 6th April 1984 IMPORTANT, PLEASE READ 536 Wants, Exchanges, Lost & Found 537 EDITORIAL - This issue contains many interesting contributions, many of which discuss various aspects of biological recording. Charles Copp's paper could well provide a sound basis for discussions at the forthcoming seminar at Leicester. The contribution from Keith Francis resulted from a very interesting meeting on biological recording at Oxford County Museum under the AMSSEE flag. It is hoped that the editors may be able to include some contributions from other speakers at this meeting in a future issue. We have had our article in its finished state for over two years as an emergency reserve and now seemed like a useful time to publish it. It has been heavily biased towards biological recording of late, but that is the subject which members seem most eloquent about. -

Skomer Island Bird Report 2017

Skomer Island Bird Report 2017 Page 1 Published by: The Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales The Nature Centre Fountain Road Tondu Bridgend CF32 0EH 01656 724100 [email protected] www.welshwildlife.org For any enquiries please contact: Skomer Island c/o Lockley Lodge Martins Haven Marloes Haverfordwest Pembrokeshire SA62 3BJ 07971 114302 [email protected] Skomer Island National Nature Reserve is owned by Natural Resources Wales and managed by The Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales. More details on visiting Skomer are available at www.welshwildlife.org. Seabird monitoring on Skomer Island NNR is supported by JNCC. Page 3 Table of Contents Skomer Island Bird Report 2017 ............................................................................................................... 5 Island rarities summary 2017 .......................................................................................................................... 5 Skomer Island seabird population summary 2017 .......................................................................................... 6 Skomer Island breeding landbirds population summary 2017 ....................................................................... 7 Systematic list of birds ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Rarity Report ................................................................................................................................................ -

The Pigeon Names Columba Livia, ‘C

Thomas M. Donegan 14 Bull. B.O.C. 2016 136(1) The pigeon names Columba livia, ‘C. domestica’ and C. oenas and their type specimens by Thomas M. Donegan Received 16 March 2015 Summary.—The name Columba domestica Linnaeus, 1758, is senior to Columba livia J. F. Gmelin, 1789, but both names apply to the same biological species, Rock Dove or Feral Pigeon, which is widely known as C. livia. The type series of livia is mixed, including specimens of Stock Dove C. oenas, wild Rock Dove, various domestic pigeon breeds and two other pigeon species that are not congeners. In the absence of a plate unambiguously depicting a wild bird being cited in the original description, a neotype for livia is designated based on a Fair Isle (Scotland) specimen. The name domestica is based on specimens of the ‘runt’ breed, originally illustrated by Aldrovandi (1600) and copied by Willughby (1678) and a female domestic specimen studied but not illustrated by the latter. The name C. oenas Linnaeus, 1758, is also based on a mixed series, including at least one Feral Pigeon. The individual illustrated in one of Aldrovandi’s (1600) oenas plates is designated as a lectotype, type locality Bologna, Italy. The names Columba gutturosa Linnaeus, 1758, and Columba cucullata Linnaeus, 1758, cannot be suppressed given their limited usage. The issue of priority between livia and domestica, and between both of them and gutturosa and cucullata, requires ICZN attention. Other names introduced by Linnaeus (1758) or Gmelin (1789) based on domestic breeds are considered invalid, subject to implicit first reviser actions or nomina oblita with respect to livia and domestica. -

Pest Risk Assessment

PEST RISK ASSESSMENT Indian ringneck parrot Psittacula krameri Photo: Garg 2007. Image from Wikimedia Commons licenced under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported April 2011 This publication should be cited as: Latitude 42 (2011) Pest Risk Assessment: Indian ringneck parrot (Psittacula krameri). Latitude 42 Environmental Consultants Pty Ltd. Hobart, Tasmania. About this Pest Risk Assessment This pest risk assessment is developed in accordance with the Policy and Procedures for the Import, Movement and Keeping of Vertebrate Wildlife in Tasmania (DPIPWE 2011). The policy and procedures set out conditions and restrictions for the importation of controlled animals pursuant to s32 of the Nature Conservation Act 2002. For more information about this Pest Risk Assessment, please contact: Wildlife Management Branch Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Address: GPO Box 44, Hobart, TAS. 7001, Australia. Phone: 1300 386 550 Email: [email protected] Visit: www.dpipwe.tas.gov.au Disclaimer The information provided in this Pest Risk Assessment is provided in good faith. The Crown, its officers, employees and agents do not accept liability however arising, including liability for negligence, for any loss resulting from the use of or reliance upon the information in this Pest Risk Assessment and/or reliance on its availability at any time. Pest Risk Assessment: Indian ringneck parrot Psittacula krameri 2/19 1. Summary The Indian ringneck parrot (Psittacula krameri) is a pale yellow-green parrot with a distinguishing long tail which lives in tropical and subtropical lightly wooded habitats in Africa and Asia. It feeds mainly on seeds, fruit, flowers and nectar. -

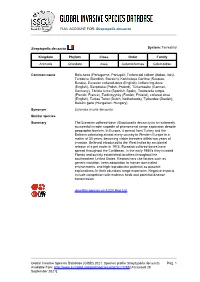

Streptopelia Decaocto Global Invasive Species Database (GISD)

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Streptopelia decaocto Streptopelia decaocto System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Aves Columbiformes Columbidae Common name Rola-turca (Portuguese, Portugal), Tortora dal collare (Italian, Italy), Turkduva (Swedish, Sweden), Kolchataya Gorlitsa (Russian, Russia), Eurasian collared-dove (English), Indian ring-dove (English), Sierpówka (Polish, Poland), Türkentaube (German, Germany), Tórtola turca (Spanish, Spain), Tourterelle turque (French, France), Turkinkyyhky (Finnish, Finland), collared dove (English), Turkse Tortel (Dutch, Netherlands), Tyrkerdue (Danish), Balkáni gerle (Hungarian, Hungary) Synonym Columba risoria decaocto Similar species Summary The Eurasian collared-dove (Streptopelia decaocto) is an extremely successful invader capable of phenomenal range expansion despite geographic barriers. In Europe, it spread from Turkey and the Balkans colonizing almost every country in Western Europe in a matter of 30 years, becoming viable breeders within two years of invasion. Believed introduced to the West Indies by accidental release of a pet trader in 1974, Eurasian collared-doves have spread throughout the Caribbean. In the early 1980's they invaded Florida and quickly established localities throughout the southeastern United States. Researchers cite factors such as genetic mutation, keen adaptation to human-dominated environments, and high reproductive potential as possible explanations for their abundant range expansion. Negative impacts include competition with endemic birds and potential disease transmission. view this species on IUCN Red List Global Invasive Species Database (GISD) 2021. Species profile Streptopelia decaocto. Pag. 1 Available from: http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/species.php?sc=1269 [Accessed 28 September 2021] FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Streptopelia decaocto Species Description The Eurasian collared-dove (Streptopelia decaocto) is a stocky, medium-sized dove. -

Turtle Doves (Streptopelia Turtur Linnaeus, 1758) in Saudi Arabia

LIFE14 PRE/UK/000002 International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the European Turtle-dove Streptopelia turtur (2018 to 2028) European Union (EU) International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the European Turtle-dove Streptopelia turtur LIFE14 PRE/UK/000002 Project May 2018 Produced by Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) Prepared in the framework of the EuroSAP (LIFE14 PRE/UK/000002) LIFE preparatory project, coordinated by BirdLife International and co-financed by the European Commission Directorate General for the Environment, the African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement (AEWA), and each of the project partners Disclaimer and date of adoption/approval: - Approved at the European Union Nature Directives Expert Group meeting on the 22-23 May 2018 by Member States of the European Union, with the following disclaimer: “Malta, Spain, Italy, Romania and and the Federation of Associations for Hunting and Conservation of the EU (FACE) do not support measure 3.1.1 "Implement a temporary hunting moratorium until an adaptive harvest management modelling framework (Action 3.2.1) is developed”; Bulgaria, Cyprus and Greece do not approve the Species Action Plan because of the inclusion of measure 3.1.1.; France considers that measure 3.1.1 is not relevant on its territory because it will implement an adaptive harvest management modelling framework from the beginning of 2019; Portugal will support Action 3.1.1 only if it is applied in all Member-states along the western flyway range, in order to be effective; Austria opposes the moratorium, since it considers it goes beyond the requirements of the Birds Directive.” - Adopted by the 48th meeting of the CMS Standing Committee on 23-24 October 2018. -

Checklists of Protected and Threatened Species in Ireland. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No

ISSN 1393 – 6670 N A T I O N A L P A R K S A N D W I L D L I F E S ERVICE CHECKLISTS OF PROTECTED AND THREATENED SPECIES IN IRELAND Brian Nelson, Sinéad Cummins, Loraine Fay, Rebecca Jeffrey, Seán Kelly, Naomi Kingston, Neil Lockhart, Ferdia Marnell, David Tierney and Mike Wyse Jackson I R I S H W I L D L I F E M ANUAL S 116 National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) commissions a range of reports from external contractors to provide scientific evidence and advice to assist it in its duties. The Irish Wildlife Manuals series serves as a record of work carried out or commissioned by NPWS, and is one means by which it disseminates scientific information. Others include scientific publications in peer reviewed journals. The views and recommendations presented in this report are not necessarily those of NPWS and should, therefore, not be attributed to NPWS. Front cover, small photographs from top row: Coastal heath, Howth Head, Co. Dublin, Maurice Eakin; Red Squirrel Sciurus vulgaris, Eddie Dunne, NPWS Image Library; Marsh Fritillary Euphydryas aurinia, Brian Nelson; Puffin Fratercula arctica, Mike Brown, NPWS Image Library; Long Range and Upper Lake, Killarney National Park, NPWS Image Library; Limestone pavement, Bricklieve Mountains, Co. Sligo, Andy Bleasdale; Meadow Saffron Colchicum autumnale, Lorcan Scott; Barn Owl Tyto alba, Mike Brown, NPWS Image Library; A deep water fly trap anemone Phelliactis sp., Yvonne Leahy; Violet Crystalwort Riccia huebeneriana, Robert Thompson Main photograph: Short-beaked Common Dolphin Delphinus delphis, -

Some Calls and Displays of the Picazuro Pigeon (Columba Picazuro) Are Described and Compared with Those of Other Speciesof Pigeons

418 Vol. 66 SOME CALLS AND DISPLAYS OF THE PICAZTJRO PIGEON By DEREK GOODWIN For the past two years I have made occasional observations at the London Zoo on a captive Picazuro Pigeon (Columba picazuro) from Argentina. In March, 1962, I spent four days at the Chester Zoo and devoted some time each day to watching several Picazuro Pigeons in a large aviary. One pair of these birds was beginning to nest. My observations are, obviously, very incomplete but seem worth recording as I can find no detailed descriptions of the calls or behavior patterns of this pigeon in the literature, apart from various renderings of the advertising coo and a description of the display flight as being like that of the Rock Dove, CoZumba Ziz& (Wetmore, 1926). I have used the same terminology (Goodwin, 1956~) that I previously employed when discuss- ing some Old World species of pigeons, as they seem equally useful for the Picazuro Pigeon. GENERAL APPEARANCE AND GAIT Columba picezuro walks on the ground with a more agile and less waddling manner than does the Wood Pigeon (Columba palumbus). It appears to me closer in this re- spect to such ground feeding species as the Rock Dove or Stock Dove (C. oenas). It has been described (Hudson, 1920: 154-155) as being extremely like the Wood Pigeon in all respects except color. Wetmore (1926), however, gives a fuller description of its gait, flight, and appearance in the wild which suggeststhat, as speciesof Columba go, it does not in the least resemble the Wood Pigeon. This confirms the.impression I have from captive individuals. -

Pigeon and Dove CAMP 1993.Pdf

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR PIGEONS AND DOVES Report from a Workshop held 10-13 March 1993 San Diego, CA Edited by Bill Toone, Sue Ellis, Roland Wirth, Ann Byers, and Ulysses Seal Compiled by the Workshop Participants A Collaborative Effort of the ICBP Pigeon and Dove Specialist Group IUCN/SSC Captive Breeding Specialist Group Bi?/rire·INTERNATIONAL The work of the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by generous contributions from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council Conservators ($10,000 and above) Fort Wayne Zoological Society Banham Zoo Belize Zoo Australasian Species Management Program Gladys Porter Zoo Copenhagen Zoo Claws 'n Paws Chicago Zoological Society Indianapolis Zoological Society Cotswold Wildlife Park Darmstadt Zoo Columbus Zoological Gardens International Aviculturists Society Dutch Federation of Zoological Gardens Dreher Park Zoo Denver Zoological Gardens Japanese Association of Zoological Parks Erie Zoological Park Fota Wildlife Park Fossil Rim Wildlife Center and Aquariums Fota Wildlife Park Great Plains Zoo Friends of Zoo Atlanta Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust Givskud Zoo Hancock House Publisher Greater Los Angeles Zoo Association Lincoln Park Zoo Granby Zoological Society Kew Royal Botanic Gardens International Union of Directors of The Living Desert International Zoo Veterinary Group Lisbon Zoo Zoological Gardens Marwell Zoological Park Knoxville Zoo Miller Park Zoo Metropolitan Toronto Zoo Milwaukee County Zoo National Geographic Magazine Nagoya Aquarium Minnesota Zoological Garden NOAHS Center National Zoological Gardens National Audubon Society-Research New York Zoological Society North of England Zoological Society, of South Africa Ranch Sanctuary Omaha's Henry Doody Zoo Chester Zoo Odense Zoo National Aviary in Pittsburgh Saint Louis Zoo Oklahoma City Zoo Orana Park Wildlife Trust Parco Faunistico "La Torbiera" Sea World, Inc.