A Theater by Any Other Name

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communities of Resistance

COMMUNITIES OF RESISTANCE: HOW ORDINARY PEOPLE DEVELOPED CREATIVE RESPONSES TO MARGINALIZATION IN LYON AND PITTSBURGH, 1980-2010 by Daniel Holland Bachelor of Arts, Carnegie Mellon University, 1991 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2015 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Daniel Holland It was defended on March 7, 2019 and approved by Sabina Deitrick, Associate Professor, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs Laurence Glasco, Associate Professor, Department of History Rob Ruck, Professor, Department of History Committee Chair: Ted Muller, Professor, Department of History !ii Copyright © by Daniel Holland 2019 !iii Communities of Resistance: How ordinary people developed creative responses to marginalization in Lyon and Pittsburgh, 1980-2010 Daniel Holland, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 Abstract In the 1980s and 1990s, several riots erupted in suburbs, or banlieues in French, outside of Lyon, France, involving clashes between youth and police. They were part of a series of banlieue rebellions throughout France during these decades. As a result, to some French the banlieues became associated exclusively with “minority,” otherness, lawlessness, and hopelessness. Meanwhile, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the 1980s and 1990s was reeling from a -

The Leeding Edge Shaking Off Its Polluted Past, Pittsburgh Is Becoming a Center of Smart Design and Green Building

SUMMER 2002 The Magazine of The Heinz Endowments The LEEDing Edge Shaking off its polluted past, Pittsburgh is becoming a center of smart design and green building. INSIDE: Girls Count On Stage in East Liberty inside Founded more than four decades Our fields of emphasis include apart, the Howard Heinz Endowment, philanthropy in general and the established in 1941, and the Vira I. disciplines represented by our grant- Heinz Endowment, established in 1986, making programs: Arts & Culture; are the products of a deep family Children, Youth & Families; Economic commitment to community and the Opportunity; Education; and the common good that began with Environment. These five programs work H. J. Heinz and continues to this day. together on behalf of three shared The Heinz Endowments is based in organizational goals: enabling south- Pittsburgh, where we use our region western Pennsylvania to embrace and as a laboratory for the development realize a vision of itself as a premier of solutions to challenges that are place both to live and to work; making national in scope. Although the majority the region a center of quality learning of our giving is concentrated within and educational opportunity; and southwestern Pennsylvania, we work making diversity and inclusion defining wherever necessary, including statewide elements of the region’s character. and nationally, to fulfill our mission. That mission is to help our region thrive as a whole community — economically, ecologically, educationally and culturally— while advancing the state of knowledge and practice in the fields in which we work. h magazine is a publication of The Heinz Endowments. At the Endowments, we are committed to promoting learning in philanthropy and in the specific fields represented by our grantmaking programs. -

PHLF News Publication

Protecting the Places that Make Pittsburgh Home Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation Nonprofit Org. 100 West Station Square Drive, Suite 450 U. S. Postage Pittsburgh, PA 15219-1134 PAID www.phlf.org Pittsburgh, PA Address Service Requested Permit No. 598 PHLF News Published for the members of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation No. 164 June 2003 The New Markets Tax Credit Program and In this issue: 2 How It Applies to Historic Preservation Our Work: Recent Progress On April 15, 2003, Landmarks invited representatives of local community 6 organizations and lending institutions, Preservation Scene: Successes, architects, and developers to Manchester Alerts, and Losses Citizens Corporation headquarters to learn about the New Markets Tax Credit 10 program. The meeting, sponsored by The Homestead Area: Landmarks, was chaired by Stanley Lowe, serving in his dual roles as vice- Revitalization Efforts president of community revitalization of the National Trust for Historic 12 Preservation, and as Landmarks’ vice- The Challenge Facing Carnegie president for Preservation Services. The Libraries and Preservationists speakers were John Leith-Tetrault of the National Trust and Kevin McQueen, 20 a private consultant; Leith-Tetrault described the program and McQueen Events: June–October reviewed the application process. Penn Avenue in East Liberty: an area that could benefit from the New Markets Tax Credit program. NMTC helps revitalize urban main streets by stimulating new business development. Program Purpose, Allocations, and Certification In order to qualify for an allocation Allegheny Avenues, entrepreneur Jim The Northside Community The New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC) of tax credits under the NMTC Genstein is breathing new life into the Development Fund received a New program was created by Congress as program, organizations, developers, historic Buhl Optical building. -

East Liberty's Green Vision

East Liberty’s Green Vision Funding provided by: The Heinz Endowments PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Roy A. Hunt Foundation Executive Summary Advisory Committee Consultant Team John Schombert 3 Rivers Wet Weather Inc. Perkins Eastman Janie French 3 Rivers Wet Weather Inc. Stefani Danes, AIA LEED AP Marijke Hecht Western Pennsylvania Conservancy TreeVitalize Thomas Bartnik, AICP LEED AP Jeff Bergman 9 Mile Run Watershed Association Roland Baer, AIA Scott Bricker Bike Pittsburgh Arch Pelley, AIA Jeb Feldman City of Braddock Ann Gerace Conservation Consultants, Inc. Lauren Merski Jack Machek PA Department of Community Economic Development Melissa Annet Ellen Kight Pittsburgh Partnership for Neighborhood Development Sammy Van den Heuvel Monica Hoffman PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Patrice Fowler-Searcy East Liberty Presbyterian Church Cahill Associates Danielle Crumrine Tree Pittsburgh Thomas Cahill Matthew Erb Tree Pittsburgh Courtney Marm Eamon Geary Green Building Alliance Rebecca Flora Green Building Alliance Viridian Landscape Studio Caren Glotfelty The Heinz Endowments Tavis Dockwiller Janice Seigle Highmark Rolf Sauer Malik Bankston Kingsley Association Pat Buddemeyer Mellon’s Orchard Neighborhood Association Suzanna Fabry Gary Cirrincione Negley Place Neighborhood Alliance Robbie Ali Pitt Center for Healthy Environments and Communities ETM Associates David Jahn Pittsburgh City Forestry Division Timothy Marshall Noor Ismael Pittsburgh City Planning Dan Sentz Pittsburgh City Planning Pat Hassett -

National Register of Historic Places PHLF Historic Plaques Program Historical Markers Table F-1 National Register of Historic Places

Appendix F (Chapter 6: Cultural Resources) National Register of Historic Places PHLF Historic Plaques Program Historical Markers Table F-1 National Register of Historic Places Resource Name City Listed Sauer Buildings Historic District Aspinwall 9/11/1985 Davis Island Lock and Dam Site Avalon 8/29/1980 McKees Rocks Bridge Bellevue 11/14/1988 St. Nicholas Croatian Church Millvale 5/6/1980 Oakmont Country Club Historic District Oakmont 8/17/1984 Alpha Terrace Historic District Pittsburgh 7/18/1985 Byrnes & Kiefer Building Pittsburgh 3/7/1985 William Penn Hotel Pittsburgh 3/7/1985 109--115 Wood Street Pittsburgh 4/4/1996 Allegheny Cemetery Pittsburgh 12/10/1980 Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail Pittsburgh 3/7/1973 Allegheny High School Pittsburgh 9/30/1986 Allegheny Observatory Pittsburgh 6/22/1979 Allegheny Post Office Pittsburgh 7/27/1971 Allegheny River Lock and Dam No. 2 Pittsburgh 4/21/2000 Allegheny West Historic District Pittsburgh 11/2/1978 Allerdice, Taylor, High School Pittsburgh 9/30/1986 Armstrong Tunnel Pittsburgh 1/7/1986 Arsenal Junior High School Pittsburgh 9/30/1986 Baxter High School Pittsburgh 9/30/1986 Bayard School Pittsburgh 9/30/1986 Bedford School Pittsburgh 9/30/1986 Beechwood Elementary School Pittsburgh 9/30/1986 Beltzhoover Elementary School Pittsburgh 9/30/1986 Bindley Hardware Company Building Pittsburgh 8/8/1985 Birmingham Public School Pittsburgh 9/30/1986 Boggs Avenue Elementary School Pittsburgh 2/3/1987 Buhl Building Pittsburgh 1/3/1980 Burke Building Pittsburgh 9/18/1978 Butler Street Gatehouse Pittsburgh 7/30/1974 Byers-Lyons House Pittsburgh 11/19/1974 Carnegie Free Library of Allegheny Pittsburgh 11/1/1974 Carnegie Institute and Library Pittsburgh 3/30/1979 Cathedral of Learning Pittsburgh 11/3/1975 Chatham Village Historic District Pittsburgh 11/25/1998 Colfax Elementary School Pittsburgh 9/30/1986 Connelly, Clifford B., Trade School Pittsburgh 9/30/1986 Conroy Junior High School Pittsburgh 9/30/1986 Consolidated Ice Company Factory No. -

The Up-And-Coming Communities

DEVE LPittsburghOPINGSpring 2015 The Up-and-Coming Communities NAIOP PITTSBURGH ANNUAL AWARDS A CONVERSATION WITH GOVERNOR WOLF YEAR-END MARKET UPDATES HIGHEST AND ® BEST USE... opportunities and constraints strategically transformed CEC uses informed analysis to identify and harness the potential of each site’s unique conditions, creatively enhancing value while delivering a conscientious integrated design. CEC’s consulting services for the commercial, institutional, educational, retail, industrial and residential real estate markets are utilized by owners, facility managers, developers, architects and contractors at all points in a property’s life cycle. Rendering Courtesy of PNC Realty Services and Gensler Architects S e r v i c e s ► Site Selection / Due Diligence ► Land Survey ► Landscape Architecture ► Civil Engineering Services ► Geotechnical Engineering ► Construction Phase Services ► Building / Site Operation & Maintenance ► Construction Management E x p e r t i s e ► Acquisition ► Development ► Management ► Redevelopment www.cecinc.com | 800.365.2324 Austin | Boston | Bridgeport | Charlotte | Chicago | Cincinnati | Columbus | Detroit | Export | Indianapolis Knoxville | Nashville | Philadelphia | Phoenix | Pittsburgh | Sayre | Sevierville | St. Louis | Toledo | Spring 2015 05CON President's PerspectiveTE NTS 28 NAIOP Interviews Incoming Gov. Tom Wolf and Outgoing PRA President DeWitt Peart Feature 06 Developing Trend Pittsburgh’s Up-and- 39 How different is the “new” office. Coming Communities. Four communities are working to be the next Eye On the Economy hotspot for development. 45 51 Office Market Update Newmark Grubb Knight Frank 55 Industrial Market Update PA Commercial Real Estate 60 Retail Market Update Colliers International 65 Capital Markets Update 71 Legal / 23 NAIOP Pittsburgh Annual Awards Legislative Outlook Making sense of the revised Mechanics Lien Law. -

Plans to Replace Convenience Store on Hold

Volume 37, Number 5 MAY 2012 Serving Bloomfield, Friendship, Garfield, East Liberty, Lawrenceville and Stanton Heights Since 1975 Plans to Replace Convenience Store on Hold By Paula Martinac The Bulletin Bloomfield – Nick Redondo, a Bloomfield resident since 1959 and owner of the property at 300 S. Pacific that houses Brian & Cooper Food Mart, has had to temporarily suspend his plans to open a casual eatery in that location. Although Brian & Cooper proprietor Nasir Raess was given a full eight months to find another location and clear out of the building, he has failed to do so, according to Redondo. Redondo told The Bulletin that he has engaged an attorney, who is currently in negotiations with Raess’ lawyer about ABOVE: Jason Sauer of Most Wanted Fine Art is planning an art car exhibit for the fall. Read the full story on page 12. Photo by Jeff Ault vacating the premises. For more than eight years, nearby Conflict Kitchen, Waffle East Liberty – East Liberty will lose two of its most recognizable neighbors have voiced complaints about storefronts this August, when the Waffle Shop will close and Brian & Cooper, including the operation Shop Leaving East End Conflict Kitchen will relocate Downtown. A $25,000 Root Award of a back-room bar and sale of pornog- By Melinda Maloney 3 raphy. Following a series of community The Bulletin See page 3 meetings mediated by the Bloomfield- Garfield Corporation, Redondo said he Garfield – With many abandoned properties, only significant dete- “began paying closer attention to what Abandoned Buildings rioration over time allows outside forces to begin to take effect. -

PHLF News No

Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation Nonprofit Org. 100 West Station Square Drive, Suite 450 U. S. Postage Pittsburgh, PA 15219-1134 PAID www.phlf.org Pittsburgh, PA Address Service Requested Permit No. 598 Renewing Communities; Building Pride PPublishedH for the membersL ofF the PittsburghN History &ews Landmarks Foundation No. 179 December 2013 $632,000 loan in 2011 towards the In this issue restoration of seven historic properties on ColUmbUs AvenUe and Bidwell, 9 County Expands Allegheny Sheffield, and Liverpool streets” (see Together Main Street Program PHLF News No. 177, April 2011). 12 Ten Downtown Building Façades LCC’s $80,000 grant was made possible by TriState Capital Bank Being Restored Through Unique throUgh the Neighborhood Partnership Partnership Program (NPP) of the Pennsylvania 18 Twentieth-Century Architecture Department of CommUnity and Guidebook Published Economic Development. As part of 24 the NPP, a state tax-credit program Hitting the Bull’s-Eye that encoUrages bUsiness investment in commUnities, TriState Capital Bank has committed $600,000 over six years to restoration work in Manchester. I am proud “TriState Capital Bank has been a terrific to consider myself partner in fUnding the WilkinsbUrg NPP a member of PHLF and am with the WilkinsbUrg CommUnity always talking PHLF up to my Development Corporation and PHLF,” said Michael, “and their sUpport now family, friends, and neighbors. in Manchester means a great deal to Us.” What a valuable regional Robert BaUmbach is the architect for resource and community the renovation of 1401 ColUmbUs AvenUe and Alliance ConstrUction GroUp is strengthening/revitalizing the general contractor. Manchester The October 4, 2013, press conference in Manchester (from left): Pittsburgh City organization. -

Portfolio Social Corners

3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Resume.....................................................................................................................................................................5 [thesis] Ex-Libris: Citizen....................................................................................................................7 Baum-Centre Corridor...........................................................................................................................................13 Nexus......................................................................................................................................................................21 REBECCA LEFKOWITZ Afterglow: Urban Beach.........................................................................................................................................31 Architecture & Urban Design Portfolio Social Corners........................................................................................................................................................45 [thesis] Glitch......................................................................................................................................59 Permeating the Identity Frontier.............................................................................................................................75 Farm as Fiction...................................................................................................................................85 Sketchbook.......................................................................................................................................101 -

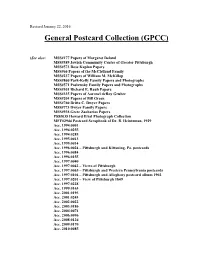

Postcard Collection Library

Revised January 22, 2016 General Postcard Collection (GPCC) (See also: MSS#177 Papers of Margaret Deland MSS#389 Jewish Community Center of Greater Pittsburgh MSS#573 Rose Kaplan Papers MSS#66 Papers of the McClelland Family MSS#237 Papers of William M. McKillop MSS#860 Park-Kelly Family Papers and Photographs MSS#571 Paslawsky Family Papers and Photographs MSS#301 Richard E. Rauh Papers MSS#335 Papers of Aaronel deRoy Gruber MSS#204 Papers of Bill Green MSS#760 Britta C. Dwyer Papers MSS#773 Dwyer Family Papers MSS#938 Grete Zacharias Papers PSS#035 Howard Etzel Photograph Collection MFF#2944 Postcard Scrapbook of Dr. B. Heintzman, 1929 Acc. 1994.0001 Acc. 1994.0255 Acc. 1994.0285 Acc. 1995.0013 Acc. 1995.0014 Acc. 1996.0024 – Pittsburgh and Kittaning, Pa. postcards Acc. 1996.0084 Acc. 1996.0155 Acc. 1997.0040 Acc. 1997.0042 – Views of Pittsburgh Acc. 1997.0065 – Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania postcards Acc. 1997.0104 – Pittsburgh and Allegheny postcard album 1902 Acc. 1997.0201 – View of Pittsburgh 1849 Acc. 1997.0228 Acc. 1999.0163 Acc. 2001.0195 Acc. 2001.0243 Acc. 2002.0022 Acc. 2003.0186 Acc. 2004.0074 Acc. 2006.0096 Acc. 2008.0126 Acc. 2009.0170 Acc. 2010.0085 Postcard Collection Inventory, Page # 2 of 81 Acc. 2011.0171 – Interesting Views of Pittsburgh postcard book Acc. 2011.0218 – Pittsburgh and Western Pa. Acc. 2011.0292 – Gateway Center, Point, Downtown Acc. 2014.0017) (Book Resources: Search Postcard History Series in catalog Greetings from Pittsburgh: A Picture Postcard History/Ralph Ashworth - F159.3.P643 A84 1992 q A Pennsylvania Album: picture postcards 1900-1930/George Miller - F150.M648 long Riverlife: Postcards from the Rivers/Riverlife Task Force – HT177 .P5 P6 2002 long Box 1 Pittsburgh Aviaries Conservatory Aviary Churches All Saints Episcopal- Allegheny Bethany Evangelical Lutheran- East Liberty Bethel Presbyterian Calvary Episcopal – Shady/Walnut Calvary United Methodist – North Side Christ Evangelical Lutheran-East End Christ Church of the Ascension – Ellsworth & Neville Christ M.E. -

2014 Western Pennsylvania History

Index 2014 WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA HISTORY FALL 2014 FALL 2014 H.J. Heinz Stephen Foster Percival L. Prattis Spring 2014 Summer 2014 Fall 2014 Winter 2014-15 Columns Architecture Around Us Legacies by Natalie Taylor & Shirley Featured Articles by Lu Donnelly Gaudette President’s message “Heinz: Much More Than 57 “Missing” Cousins, 1:10-12 Bob Butella and Sue Weigold, 2:61 by Andrew E. Masich Varieties,” by Brian Butko, 3:20-33 Abel Colley Tavern and Museum, Suzanne Kapusta, 3:61 135 Years Strong, 1:3 “Oz in the Oilfields?: Searching for L. 2:12-15 Preserving Our History, 2:3-4 Frank Baum in Bradford,” by Tim Painted Ladies, 3:10-14 Book Reviews Untitled, 3:3 Ziaukas, 2:34-47 Carnegie Free Library of McKeesport, E Block by Mark Perrott, 4:62 Pickles & Pittsburgh, 4:3 “Percival L. Prattis: The Pittsburgh 4:10-12 Over the Alleghenies: Early Canals and Courier’s Man From Chicago,” by Railroads of Pennsylvania by Robert Meadowcroft by Andrew Donovan Charles Rosenberg, 3:48-60 Neighborhood Stories Kapsh, 2:63-64 My Gun and My Axe Broken, 1:4-5 “Pittsburgh’s Famous Forgotten by Bette McDevitt Pittsburgh Pizzazz: A Life in Showbiz Point Pleasant, A Point of Radical,” by Richard Gararik, The Jazz Workshop, 1:14-15 by Patti Faloon, 2:62 Contention, 3:4-5 4:34-43 Lilly, Cambria County, 2:16-17 Robert Qualters: Autobiographical “Railroaded: How the DAR Saved the The William Penn Speakeasy, 3:14-15 Mythologies by Vicky Clark, 3:62 Fort Pitt by Alan Gutchess Fort Pitt Blockhouse,” by Emily Ballfield Farm, 4:14-15 Samuel Stouffer and the GI Survey: Pittsburgh, -

Pittsburgh Architecture Information File

Pittsburgh Architecture 1000 California (Northside) 1000 Grandview Condominiums 121 Ninth St. 1370 Washington Pike (Bridgeville) 146 45th St. (Lawrenceville) 1902 Landmark Tavern 200 West North Ave. (Northside) 411 Grand Plaza 415 Stratton Lane (Shadyside) 518 Emerson St. 525 William Penn Place (Mellon Building) 5742 Fifth Ave. Condos 5807 Fifth Ave. Condos 614 Bellefont Street (Shadyside) 6568 Fifth Ave. (Point Breeze) 826 Lincoln Ave. 841 N. Lincoln Ave (Northside) Academy Place (Glen Osborne) Air Tool Parts and Service Co. (Smallman St) Airport Alcoa Building (Downtown) Alcoa Building (Northside) Alcoa Building (proposed, East General Robinson St., Northside) Alequippa Terrace All Saints Church (Etna) Allegheny Cemetery Allegheny City Hall Allegheny Community College Allegheny County Airport Allegheny County Courthouse & Jail Allegheny County Morgue Allegheny General Hospital Allegheny International Inc. Proposed Headquarters Allegheny Observatory Allegheny Tower Apartments Allegheny West (Northside) Allegheny-Kiski Valley Heritage Museum (Tarentum) Allison Elementary School (Wilkinsburg) Alpha Terrace (Highland Park) Aluise, John & Angela House (Bellevue) Aluminum Company of America Building Alzheimer?s Alliance Care & Research Center (proposed) American Institute of Architects Ammons, Tom Home (Hampton Twp.) Anderson Manor (Manchester) Apartment Building (Alder & S. Highland) Apartment House (Shadyside) APICS Castle Appletree Bed & Breakfast Architects Workshop Architectural Club Armstrong Cork Co. ? Armstrong Square (Strip District) Armstrong, Richard House Armstrong, Robert III (Covert Rd., Lawrence County near New Castle) Arrott Building (Downtown) Art Deco Art Moderne Arts & Crafts Aspinwall Presbyterian Church Atlantic Financial Building Atlantic Refining Co. Atrium (Oakland) Avery Church (Northside) Aviary Awards B?Nai Israel Synagogue (E. Liberty) Bair, Harry S. (East End Ave.) Baker, F. J. Torrance House (Sewickley) Ballay, Joe (Penn Hills) Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Bank of Pittsburgh (John Chislett, arch) Bank, The Barns Barrow, Joseph L.