Ulus to Their Sympathies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

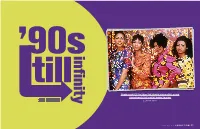

En Vogue L at Oya C R O S S

- Left to Right: Tem inimus sequiae veriatem quam, estibus amet et aborerro offici de rest, quam, tendand uscienti ut FROM QUARTET TO TRIO, THE FUNKY DIVAS STILL SHOW (AND PROVE) THEY WERE BORN TO SING :EN VOGUE L AT OYA C R O S S APRIL/MAY 2017 EBONY.COM 83 lion YouTube views. But wait, there’s connection that goes into play when to learn each of more: The sultry songstresses climbed blending voices, one that Bennett came En Vogue members, from left, Rhona Bennett, the girls and re- the charts six times with singles “Hold equipped with, Ellis explains. Terry Ellis and Cindy Herron-Braggs spect the difer- On,” “My Lovin’ (Never Gonna Get “It’s being conscious of each other ences,” says El- It),” “Free Your Mind,” “Giving Him when we’re singing,” she says. “Where lis, the youngest THE SUPREMES.The Marvelettes. Something He Can Feel,” “Don’t Let is she placing her vibrato? What’s the of fve siblings. The Pointer Sisters. Between the 1960s Go,” and “Whatta Man” featuring tempo or how is she executing this song, “For me, that’s and the 1980s, the music scene was Salt-N-Pepa. this line or this word? I never thought freeing your dominated by timeless female groups. On top of their silky siren abilities, about it, but maybe that does come with mind. I think the But when it comes to girl group dynam- pop culture embraced the clingy red some seasoning and time. Rhona is a key is to under- ics, the 1990s are defned by En Vogue— dresses the vocally gifed women se- veteran as well, so she came in with that stand that you a foursome equipped with efortless duced viewers with in the music video information and awareness already. -

En Vogue Ana Popovic Artspower National Touring Theatre “The

An Evening with Jazz Trumpeter Art Davis Ana Popovic En Vogue Photo Credit: Ruben Tomas ArtsPower National Alyssa Photo Credit: Thomas Mohr Touring Theatre “The Allgood Rainbow Fish” Photo Courtesy of ArtsPower welcome to North Central College ometimes good things come in small Ana Popovic first came to us as a support act for packages. There is a song “Bigger Isn’t Better” Jonny Lang for our 2015 homecoming concert. S in the Broadway musical “Barnum” sung by When she started on her guitar, Ana had everyone’s the character of Tom Thumb. He tells of his efforts attention. Wow! I am fond of telling people who to prove just because he may be small in stature, he have not been in the concert hall before that it’s a still can have a great influence on the world. That beautiful room that sounds better than it looks. Ana was his career. Now before you think I have finally Popovic is the performer equivalent of my boasts lost it, there is a connection here. February is the about the hall. The universal comment during the smallest month, of the year, of course. Many people break after she performed was that Jonny had better feel that’s a good thing, given the normal prevailing be on his game. Lucky for us, of course, he was. But weather conditions in the month of February in the when I was offered the opportunity to bring Ana Chicagoland area. But this little month (here comes back as the headliner, I jumped at the chance! Fasten the connection!) will have a great influence on the your seatbelts, you are in for an amazing evening! fine arts here at North Central College with the quantity and quality of artists we’re bringing to you. -

Billboard-1997-08-30

$6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) $5.95 (U.S.), IN MUSIC NEWS BBXHCCVR *****xX 3 -DIGIT 908 ;90807GEE374EM0021 BLBD 595 001 032898 2 126 1212 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE APT A LONG BEACH CA 90807 Hall & Oates Return With New Push Records Set PAGE 1 2 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT AUGUST 30, 1997 ADVERTISEMENTS 4th -Qtr. Prospects Bright, WMG Assesses Its Future Though Challenges Remain Despite Setbacks, Daly Sees Turnaround BY CRAIG ROSEN be an up year, and I think we are on Retail, Labels Hopeful Indies See Better Sales, the right roll," he says. LOS ANGELES -Warner Music That sense of guarded optimism About New Releases But Returns Still High Group (WMG) co- chairman Bob Daly was reflected at the annual WEA NOT YOUR BY DON JEFFREY BY CHRIS MORRIS looks at 1997 as a transitional year for marketing managers meeting in late and DOUG REECE the company, July. When WEA TYPICAL LOS ANGELES -The consensus which has endured chairman /CEO NEW YORK- Record labels and among independent labels and distribu- a spate of negative m David Mount retailers are looking forward to this tors is that the worst is over as they look press in the last addressed atten- OPEN AND year's all- important fourth quarter forward to a good holiday season. But few years. Despite WARNER MUSI C GROUP INC. dees, the mood with reactions rang- some express con- a disappointing was not one of SHUT CASE. ing from excited to NEWS ANALYSIS cern about contin- second quarter that saw Warner panic or defeat, but clear -eyed vision cautiously opti- ued high returns Music's earnings drop 24% from last mixed with some frustration. -

California State University, Northridge

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE THE SPATIAL PRACTICES OF SOUL REBEL RADIO IN LOS ANGELES’ THIRD WORLD LEFT A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Chicano and Chicana Studies By Miguel Paredes August 2012 The thesis of Miguel Paredes is approved: _________________________ ______________________ Professor Yreina D. Cervántez Date _________________________ ______________________ Dr. Gabriel Gutierrez Date _________________________ _______________________ Dr. David Rodriguez, Chair Date ii Dedication To the young people in Los Angeles, to the working class communities in the Third World Left throughout Southern California especially Elysian Valley aka “Frogtown” in Northeast LA, to the over 50 members of the Soul Rebel Radio collective especially the founding members Eduardo, Laura, Javier, Jose, Tito, Teresa, Hasmik, Jorge, XL, Travis, Oriel, and Lex, to the KPFK staff and audience, to the staff of the CSUN Chican@ Studies Department especially Dr. Rudy Acuña, Dr. Alberto Garcia, Harry Gamboa, Fermin Herrera, Dr. Mary Pardo, Dr. Gabriel Gutierrez, Yreina D. Cervántez, Dr. Jorge Garcia, Ruben Mendoza, and posthumously dedicated to Roberto Sifuentes , Dr. Shirlene Soto, and “Toppy” Flores. To my family especially my mother Lucila Paredes, my father Miguel Paredes Sr., my brother Adrian Paredes, my sister Gabriela Paredes and her daughter Dahlila and son Ivan, my brother Daniel Paredes, and his son Diego, to my best friends Mike and Guzman, to my godchildren Juliette, Justin, Isaac, Elia, and Ehecatl, and to the Fe@s including Pascual, Mixpe, and Chris, but particularly to Ixya Herrera for giving me the motivation and support to complete my Master’s Degree in Chican@ Studies. -

Nr Kat EAN Code Artist Title Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data Premiery Repertoire 19075816441 190758164410 '77 Bright Gloom Vinyl

nr kat EAN code artist title nośnik liczba nośników data premiery repertoire 19075816441 190758164410 '77 Bright Gloom Vinyl Longplay 33 1/3 2 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 19075816432 190758164328 '77 Bright Gloom CD Longplay 1 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 9985848 5051099858480 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us CD Longplay 1 2015-10-30 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 88697636262 886976362621 *NSYNC The Collection CD Longplay 1 2010-02-01 POP 88875025882 888750258823 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC CD Longplay 2 2014-11-11 POP 19075906532 190759065327 00 Fleming, John & Aly & Fila Future Sound of Egypt 550 CD Longplay 2 2018-11-09 DISCO/DANCE 88875143462 888751434622 12 Cellisten der Berliner Philharmoniker, Die Hora Cero CD Longplay 1 2016-06-10 CLASSICAL 88697919802 886979198029 2CELLOS 2CELLOS CD Longplay 1 2011-07-04 CLASSICAL 88843087812 888430878129 2CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 1 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 88875052342 888750523426 2CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 2 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 88725409442 887254094425 2CELLOS In2ition CD Longplay 1 2013-01-08 CLASSICAL 19075869722 190758697222 2CELLOS Let There Be Cello CD Longplay 1 2018-10-19 CLASSICAL 88883745419 888837454193 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD Video Longplay 1 2013-11-05 CLASSICAL 88985349122 889853491223 2CELLOS Score CD Longplay 1 2017-03-17 CLASSICAL 88985461102 889854611026 2CELLOS Score (Deluxe Edition) CD Longplay 2 2017-08-25 CLASSICAL 19075818232 190758182322 4 Times Baroque Caught in Italian Virtuosity CD Longplay 1 2018-03-09 CLASSICAL 88985330932 889853309320 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones -

REGLEMENT Jeu « Sony Days 2018 »

REGLEMENT Jeu « Sony Days 2018 » Article 1. - Sociétés Organisatrices Sony Interactive Entertainment ® France SAS, au capital de 40 000 €, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre sous le N° 399 930 593, située 92 avenue de Wagram, 75017 Paris ; Sony Mobile Communications, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre sous le n°439 961 905, située 49-51 quai de Dion Bouton 92800 Puteaux ; Sony Pictures Home Entertainment France SNC, au capital de 107 500 €, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre en date du 02/03/1987 sous le N° 324 834 266, située 25 quai Gallieni, 92150 Suresnes ; Sony Music Entertainment, France, SAS au capital de 2.524.720 €, enregistrée au RCS de Paris sous le n°542 055 603, située 52/54, rue de Châteaudun, 75009 Paris ; SONY France , succursale de Sony Europe Limited, 49-51 quai de Dion Bouton 92800 Puteaux , RCS Nanterre 390 711 323 (ci-après les « Sociétés Organisatrices ») ; organise un jeu avec obligation d’achat uniquement dans les magasins Fnac et Darty ainsi que sur le sites www.fnac.com et www.darty.com (ci-après le « Jeu ») par le biais d’instants gagnants ouverts du 02/04/2018 10h au 15/04/2018 23h59 inclus ouvert aux personnes physiques majeures (sous réserve des dispositions indiquées à l’article 2) résidant en France Métropolitaine (Corse et DROM-COM exclus). Article 2. - Participation Ce jeu est ouvert à toute personne physique majeure, résidant en France métropolitaine (Corse et DROM-COM exclus), à l'exception des mineurs, du personnel de la société organisatrice et des membres des sociétés partenaires de l'opération ainsi que de leur famille en ligne directe. -

Flower Essence Repertory Acomprehensive Guide to North American and English Flower Essences for Emotional and Spiritual Well-Being

Flower Essence Repertory AComprehensive Guide to North American and English Flower Essences for Emotional and Spiritual Well-Being by Patricia Kaminski and Richard Katz Flower Essence Repertory by Patricia Kaminski & Richard Katz A Comprehensive Guide to North American and English Flower Essences for Emotional and Spiritual Well-Being Published by The Flower Essence Society a division of the non-profit educational and research organization Earth-Spirit, Inc. P.O. Box 459 Nevada City, CA 95959 USA Telephone: 800-736-9222 530-265-9163 Fax: 530-265-0584 www.flowersociety.org [email protected] © by the Flower Essence Society, a division of Earth-Spirit, Inc., a non-profit educational and research organization. ISBN 0-9631306-1-7 All rights reserved in all countries. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. No translation of this work, or of any portion of this work, may be published or included in any publication without the written authorization of the publisher. This E-Book edition is offered as a courtesy to Flower Essence Society members while a new print edition of the Flower Essence Repertory is in preparation. Printed copies are allowed only for personal and non-commercial use, or use in a private practice. Acknowledgments To Dr. Edward Bach for his original indications regarding the 39 English remedies that are included in this Repertory; and for the further insights of many practitioners, especially the insights of Julian Barnard (The Healing Herbs of Edward Bach), Mechthild Scheffer (Bach Flower Therapy), and Phillip M. -

Dawn Robinson Has Been a Major Player in the Music Business Since Her First Chart- Topping Single with En Vogue in 1990

Dawn Robinson has been a major player in the music business since her first chart- topping single with En Vogue in 1990. She’s graced the covers of influential publications like Vogue, Rolling Stone and USA Today, had endorsement deals with Coca-Cola, Converse (with former NBA Guard, Mayor Kevin Johnson) and Japanese cellular brand MOVA, and recently appeared on US TV show The View. After 20 years at the top, she’s still creating new music and touring the world. Her music is critically acclaimed and she has an incredibly loyal fan base, which has supported her since her days with En Vogue and Lucy Pearl. She reflects, “Wow, when I think about my life as an artist, I’m so grateful for our amazing fans, and that they still love us after all these years. Because of them, we were listed in the 2009 USA Today Concert-Series edition as one of the biggest selling touring acts, along with Gwen Stefani and others. That’s a great achievement and we don’t take anything for granted”. Now, Dawn is raising the bar yet again with a monumental project; an explosive solo album that will set new standards for Rock and R&B. “I am very excited about the direction of my new journey and although I will not appear on En Vogue’s upcoming album, my girls and I have a spiritual bond. I love and support Cindy, Max and Terry and I am still touring with them indefinitely.” says Dawn. “The renaissance of Dawn is going to be fierce; her music is intoxicating and her performance is like never before, a modern interpretation of Funky Diva,” says her manager, Nick. -

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Local 1 Luke I Wanna Rock 4:23 Luke - Greatest Hits 8 1996 Rap 128 Disk Local 2 Angie Stone No More Rain (In this Cloud) 4:42 Black Diamond 1999 Soul 3 128 Disk Local 3 Keith Sweat Merry Go Round 5:17 I'll Give All My Love to You 4 1990 RnB 128 Disk Local 4 D'Angelo Brown Sugar (Live) 10:42 Brown Sugar 1 1995 Soul 128 Disk Grand Verbalizer, What Time Is Local 5 X Clan 4:45 To the East Blackwards 2 1990 Rap 128 It? Disk Local 6 Gerald Levert Answering Service 5:25 Groove on 5 1994 RnB 128 Disk Eddie Local 7 Intimate Friends 5:54 Vintage 78 13 1998 Soul 4 128 Kendricks Disk Houston Local 8 Talk of the Town 6:58 Jazz for a Rainy Afternoon 6 1998 Jazz 3 128 Person Disk Local 9 Ice Cube X-Bitches 4:58 War & Peace, Vol.1 15 1998 Rap 128 Disk Just Because God Said It (Part Local 10 LaShun Pace 9:37 Just Because God Said It 2 1998 Gospel 128 I) Disk Local 11 Mary J Blige Love No Limit (Remix) 3:43 What's The 411- Remix 9 1992 RnB 3 128 Disk Canton Living the Dream: Live in Local 12 I M 5:23 1997 Gospel 128 Spirituals Wash Disk Whitehead Local 13 Just A Touch Of Love 5:12 Serious 7 1994 Soul 3 128 Bros Disk Local 14 Mary J Blige Reminisce 5:24 What's the 411 2 1992 RnB 128 Disk Local 15 Tony Toni Tone I Couldn't Keep It To Myself 5:10 Sons of Soul 8 1993 Soul 128 Disk Local 16 Xscape Can't Hang 3:45 Off the Hook 4 1995 RnB 3 128 Disk C&C Music Things That Make You Go Local 17 5:21 Unknown 3 1990 Rap 128 Factory Hmmm Disk Local 18 Total Sittin' At Home (Remix) -

The Ice Break"

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explana )n of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

BB-1995-07-22.Pdf

$5.50 (U.S.), $6.50 (CAN.), £4.50 (U.K.) IN MUSIC NEWS *BXNCCVR ******** 3 -DIGIT 908 MCA Primes tGEE4EM740M099074$ 002 0663 000 BI MAR 2396 1 03 MONTY GREENLY Fans For 3740 ELM AVE APT A LONG BEACH, CA 90807 -3402 Buffett's `Barometer Soup' SEE PAGE 10 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT JULY 22, 1995 ADVERTISEMENTS TICKETMASTER RIVALS SEEK NEW BIZ Sony's `Spirit BY ERIC BOEHLERT competition. That's because a handful More than 20 years ago, while sitting of challengers covering a patchwork of in the stands at an Arizona State Uni- Of '73' Rocks NEW YORK -Ever since it pur- regions are bidding and occasionally versity football game, computer pro- chased assets from once -mighty com- winning contracts to provide the same grammer Dorothy McLaughlin joined petitor Ticketron in 1991, critics have types of services that Ticketmaster of- her sister and brother-in -law, Margie For Pro -Choice charged that Ticketmaster faces no ri- fers: box -office support, phone rooms, and Bill Bliss, in a brain teaser: Why val and has cornered itself a lucrative a network of satellite outlets, and pro- couldn't tickets be sold electronically BY CHRIS MORRIS market. motional dollars. from various remote outlets, allowing congratulates The accusation, with which the Jus- Despite Ticketmaster selling 55 mil- all customers the same seat selection? LOS ANGELES -Sony 550 Music will mate activist zeal with a sense of nostalgic fun on Aug. 8, when it Carl P. Mayfield, Tele- charge Systemsó SONY Loscalzo & PROTIX. Dil1an1's lion tickets last year and its regional the staffs of competitors moving just a fraction of tice Department's recent investigation that number, the seemingly mis- At the time, companies bicycled did not concur, stems not only from the matched duels continue to unfold. -

Resonances of Chindon-Ya: Sound, Space, and Social Difference in Contemporary Japan

Resonances of Chindon-ya: Sound, Space, and Social Difference in Contemporary Japan By Marié Abe A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jocelyne Guilbault, Co-chair Professor Bonnie Wade, Co-chair Professor Alan Tansman Professor Gillian Hart Fall 2010 Resonances of Chindon-ya: Sound, Space, and Social Difference in Contemporary Japan © 2010 by Marié Abe Abstract Resonances of Chindon-ya: Sound, Space, and Social Difference in Contemporary Japan by Marié Abe Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Jocelyne Guilbault, Co-chair Professor Bonnie Wade, Co-chair This dissertation examines the intersection of sound, public space, and social difference in contemporary Japanese urban life through ethnographic analysis of a Japanese street musical practice called chindon-ya. Chindon-ya, which dates back to the 1850s, refers to groups of outlandishly costumed street musicians in Japan who are hired to advertise an employer’s business. After decades of inactivity, chindon-ya has been undergoing a resurgence since the early 1990s. Despite being labeled as anachronistic and obscure, some chindon-ya troupes today have achieved financial success generating up to one million dollars in annual income, while chindon-ya aesthetics has been taken up by rock, jazz, and experimental musicians and refashioned into hybridized musical practices. In the context of long-term economic downturn, growing socioeconomic gaps, and visually and sonically saturated urban streets, I ask how such an “outdated” means of advertisement has not only proven itself to be financially viable, but has also enabled widely varying sentiments, musical styles, translocal relations, forms of business enterprise, and political aspirations to articulate with one another.