Reincarnation; a Study of Forgotten Truth by E. D. Walker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

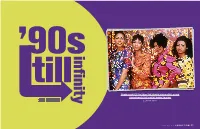

En Vogue L at Oya C R O S S

- Left to Right: Tem inimus sequiae veriatem quam, estibus amet et aborerro offici de rest, quam, tendand uscienti ut FROM QUARTET TO TRIO, THE FUNKY DIVAS STILL SHOW (AND PROVE) THEY WERE BORN TO SING :EN VOGUE L AT OYA C R O S S APRIL/MAY 2017 EBONY.COM 83 lion YouTube views. But wait, there’s connection that goes into play when to learn each of more: The sultry songstresses climbed blending voices, one that Bennett came En Vogue members, from left, Rhona Bennett, the girls and re- the charts six times with singles “Hold equipped with, Ellis explains. Terry Ellis and Cindy Herron-Braggs spect the difer- On,” “My Lovin’ (Never Gonna Get “It’s being conscious of each other ences,” says El- It),” “Free Your Mind,” “Giving Him when we’re singing,” she says. “Where lis, the youngest THE SUPREMES.The Marvelettes. Something He Can Feel,” “Don’t Let is she placing her vibrato? What’s the of fve siblings. The Pointer Sisters. Between the 1960s Go,” and “Whatta Man” featuring tempo or how is she executing this song, “For me, that’s and the 1980s, the music scene was Salt-N-Pepa. this line or this word? I never thought freeing your dominated by timeless female groups. On top of their silky siren abilities, about it, but maybe that does come with mind. I think the But when it comes to girl group dynam- pop culture embraced the clingy red some seasoning and time. Rhona is a key is to under- ics, the 1990s are defned by En Vogue— dresses the vocally gifed women se- veteran as well, so she came in with that stand that you a foursome equipped with efortless duced viewers with in the music video information and awareness already. -

En Vogue Ana Popovic Artspower National Touring Theatre “The

An Evening with Jazz Trumpeter Art Davis Ana Popovic En Vogue Photo Credit: Ruben Tomas ArtsPower National Alyssa Photo Credit: Thomas Mohr Touring Theatre “The Allgood Rainbow Fish” Photo Courtesy of ArtsPower welcome to North Central College ometimes good things come in small Ana Popovic first came to us as a support act for packages. There is a song “Bigger Isn’t Better” Jonny Lang for our 2015 homecoming concert. S in the Broadway musical “Barnum” sung by When she started on her guitar, Ana had everyone’s the character of Tom Thumb. He tells of his efforts attention. Wow! I am fond of telling people who to prove just because he may be small in stature, he have not been in the concert hall before that it’s a still can have a great influence on the world. That beautiful room that sounds better than it looks. Ana was his career. Now before you think I have finally Popovic is the performer equivalent of my boasts lost it, there is a connection here. February is the about the hall. The universal comment during the smallest month, of the year, of course. Many people break after she performed was that Jonny had better feel that’s a good thing, given the normal prevailing be on his game. Lucky for us, of course, he was. But weather conditions in the month of February in the when I was offered the opportunity to bring Ana Chicagoland area. But this little month (here comes back as the headliner, I jumped at the chance! Fasten the connection!) will have a great influence on the your seatbelts, you are in for an amazing evening! fine arts here at North Central College with the quantity and quality of artists we’re bringing to you. -

Philosophical Foundations of Health Education

PHILOSOPHICAL FOUNDATIONS OF HEALTH EDUCATION BL ACK FURNEY Philosophical Foundations of Health Education covers the philosophical and ethical foundations of the practice of health education in school, community, work site, and GRAF hospital settings, as well as in health promotion consultant activities. The book presents NOLTE personal philosophies of health educators, essential philosophical perspectives, and a range of philosophical issues that are relevant to health education practice. Philosophical PHILOSOPHICAL Foundations of Health Education is organized around the fi ve major philosophical traditions: cognitive-based, decision-making, behavior change, freeing/functioning, and social change. Co-published with the American Association for Health Education, this important work is an essential resource for student and professional. Each section contains a challenge to the reader that suggests critical thinking questions to reinforce the key points of the chapter, EDUCATION HEALTH FOUNDATIONS invite comparison with other perspectives, refl ect on the implications of the perspective, note themes that run through the chapters, and consider practical applications of the OF FOUNDATIONS PHILOSOPHICAL various philosophical approaches. The Editors OF Jill M. Black, PhD, CHES, is an associate professor in the Department of Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance at Cleveland State University and coordinator of the Community Health Education Program. She is a fellow of the American Association for Health Education. Steven R. Furney, EdD, MPH, is a professor of Health Education and director of the Division of Health Education at Texas State University. He is a fellow of the American Association for HEALTH Health Education. Helen M. Graf, PhD, is an associate professor and undergraduate program director in the Department of Health and Kinesiology at Georgia Southern University. -

American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: an Appraisal of Alexis De Tocqueville’S Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2017 American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal and the Post-World War II Welfare State John P. Varacalli The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1828 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] AMERICAN CIVIL ASSOCIATIONS AND THE GROWTH OF AMERICAN GOVERNMENT: AN APPRAISAL OF ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE’S DEMOCRACY IN AMERICA (1835- 1840) APPLIED TO FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT’S NEW DEAL AND THE POST-WORLD WAR II WELFARE STATE by JOHN P. VARACALLI A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 JOHN P. VARACALLI All Rights Reserved ii American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Post World War II Welfare State by John P. Varacalli The manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts ______________________ __________________________________________ Date David Gordon Thesis Advisor ______________________ __________________________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Acting Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. -

Billboard-1997-08-30

$6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) $5.95 (U.S.), IN MUSIC NEWS BBXHCCVR *****xX 3 -DIGIT 908 ;90807GEE374EM0021 BLBD 595 001 032898 2 126 1212 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE APT A LONG BEACH CA 90807 Hall & Oates Return With New Push Records Set PAGE 1 2 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT AUGUST 30, 1997 ADVERTISEMENTS 4th -Qtr. Prospects Bright, WMG Assesses Its Future Though Challenges Remain Despite Setbacks, Daly Sees Turnaround BY CRAIG ROSEN be an up year, and I think we are on Retail, Labels Hopeful Indies See Better Sales, the right roll," he says. LOS ANGELES -Warner Music That sense of guarded optimism About New Releases But Returns Still High Group (WMG) co- chairman Bob Daly was reflected at the annual WEA NOT YOUR BY DON JEFFREY BY CHRIS MORRIS looks at 1997 as a transitional year for marketing managers meeting in late and DOUG REECE the company, July. When WEA TYPICAL LOS ANGELES -The consensus which has endured chairman /CEO NEW YORK- Record labels and among independent labels and distribu- a spate of negative m David Mount retailers are looking forward to this tors is that the worst is over as they look press in the last addressed atten- OPEN AND year's all- important fourth quarter forward to a good holiday season. But few years. Despite WARNER MUSI C GROUP INC. dees, the mood with reactions rang- some express con- a disappointing was not one of SHUT CASE. ing from excited to NEWS ANALYSIS cern about contin- second quarter that saw Warner panic or defeat, but clear -eyed vision cautiously opti- ued high returns Music's earnings drop 24% from last mixed with some frustration. -

California State University, Northridge

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE THE SPATIAL PRACTICES OF SOUL REBEL RADIO IN LOS ANGELES’ THIRD WORLD LEFT A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Chicano and Chicana Studies By Miguel Paredes August 2012 The thesis of Miguel Paredes is approved: _________________________ ______________________ Professor Yreina D. Cervántez Date _________________________ ______________________ Dr. Gabriel Gutierrez Date _________________________ _______________________ Dr. David Rodriguez, Chair Date ii Dedication To the young people in Los Angeles, to the working class communities in the Third World Left throughout Southern California especially Elysian Valley aka “Frogtown” in Northeast LA, to the over 50 members of the Soul Rebel Radio collective especially the founding members Eduardo, Laura, Javier, Jose, Tito, Teresa, Hasmik, Jorge, XL, Travis, Oriel, and Lex, to the KPFK staff and audience, to the staff of the CSUN Chican@ Studies Department especially Dr. Rudy Acuña, Dr. Alberto Garcia, Harry Gamboa, Fermin Herrera, Dr. Mary Pardo, Dr. Gabriel Gutierrez, Yreina D. Cervántez, Dr. Jorge Garcia, Ruben Mendoza, and posthumously dedicated to Roberto Sifuentes , Dr. Shirlene Soto, and “Toppy” Flores. To my family especially my mother Lucila Paredes, my father Miguel Paredes Sr., my brother Adrian Paredes, my sister Gabriela Paredes and her daughter Dahlila and son Ivan, my brother Daniel Paredes, and his son Diego, to my best friends Mike and Guzman, to my godchildren Juliette, Justin, Isaac, Elia, and Ehecatl, and to the Fe@s including Pascual, Mixpe, and Chris, but particularly to Ixya Herrera for giving me the motivation and support to complete my Master’s Degree in Chican@ Studies. -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm. -

Theosophical Articles and Notes

THEOSOPHICAL ARTICLES AND NOTES Reprinted from Original Sources THE THEOSOPHY CO. Los Angeles 1985 ISBN 0-938998-29-3 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Scanned & edited by volunteers at the United Lodge of Theosophists, London, UK. Edited Oct 2020 & April 2021 FOREWORD The articles in this volume come from a variety of sources. They are presented here for their intrinsic worth to students of Theosophy. They are grouped according to the place of first appearance —in the Theosophist, Lucifer, the Path, and other sources. Within these groupings they are arranged chronologically. Internal evidence strongly suggests that some of them have an “adept” origin, and they are so presented. One or two articles unintentionally omitted from Theosophical Articles by H.P.B. and W.Q.J. are included. Other contributions, not identified as to author, are of a quality which makes it appropriate to reprint them here. Thus there are articles, replies and notes which appeared in the Theosophist and Lucifer, also material by Damodar K. Mavalankar, and two articles signed “Murdhna Joti” from the Path. Cicero’s “Vision of Scipio” is included by reason of H.P.B.’s briefly informative footnotes. Judge’s “Notes on the Bhagavad Gita” is a Path article which was not a part of the book of that name. Finally, there is material taken from A.P. Sinnett’s The Occult World, from the notes of Robert Bowen, a pupil of H.P.B., and also from notes found in the effects of Countess Wachtmeister, apparently taken down from dictation by H.P.B. -

Laws of Thought and Laws of Logic After Kant”1

“Laws of Thought and Laws of Logic after Kant”1 Published in Logic from Kant to Russell, ed. S. Lapointe (Routledge) This is the author’s version. Published version: https://www.routledge.com/Logic-from-Kant-to- Russell-Laying-the-Foundations-for-Analytic-Philosophy/Lapointe/p/book/9781351182249 Lydia Patton Virginia Tech [email protected] Abstract George Boole emerged from the British tradition of the “New Analytic”, known for the view that the laws of logic are laws of thought. Logicians in the New Analytic tradition were influenced by the work of Immanuel Kant, and by the German logicians Wilhelm Traugott Krug and Wilhelm Esser, among others. In his 1854 work An Investigation of the Laws of Thought on Which are Founded the Mathematical Theories of Logic and Probabilities, Boole argues that the laws of thought acquire normative force when constrained to mathematical reasoning. Boole’s motivation is, first, to address issues in the foundations of mathematics, including the relationship between arithmetic and algebra, and the study and application of differential equations (Durand-Richard, van Evra, Panteki). Second, Boole intended to derive the laws of logic from the laws of the operation of the human mind, and to show that these laws were valid of algebra and of logic both, when applied to a restricted domain. Boole’s thorough and flexible work in these areas influenced the development of model theory (see Hodges, forthcoming), and has much in common with contemporary inferentialist approaches to logic (found in, e.g., Peregrin and Resnik). 1 I would like to thank Sandra Lapointe for providing the intellectual framework and leadership for this project, for organizing excellent workshops that were the site for substantive collaboration with others working on this project, and for comments on a draft. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Paul J

CURRICULUM VITAE Paul J. Weithman Department of Philosophy Office Phone (574) 631-5182 University of Notre Dame E-Mail: [email protected] Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 http://www.nd.edu/~pweithma/ Education Harvard University Ph.D. in Philosophy, November, 1988. Dissertation: Justice, Charity and Property: The Centrality of Sin to the Political Thought of Thomas Aquinas, Directors: John Rawls and Judith Shklar M.A. in Philosophy, June, 1984 University of Notre Dame B.A. in Philosophy summa cum laude, May, 1981 Teaching Experience Glynn Family Honors Professor of Philosophy, University of Notre Dame, 2018 - present Glynn Family Honors Collegiate Professor of Philosophy, University of Notre Dame, 2013 - 2018 Professor: Department of Philosophy, University of Notre Dame, 2002 - present Associate Professor (with tenure): Department of Philosophy, University of Notre Dame, 1997 –2002 Assistant Professor: Department of Philosophy, University of Notre Dame, 1991 - 1997 Postdoctoral Visitor: Department of Philosophy, University of Notre Dame, 1990-91 Assistant Professor: Department of Philosophy, Loyola Marymount University, 1988 - 91 Teaching Assistant: Department of Philosophy, Harvard University, 1983-88 Department of Government, Harvard University, autumn 1984 Tutor: John Winthrop House, Harvard University, 1983-88 Teaching Recognition and Awards Kaneb Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching, 2006 Thomas P. Madden Award for the Outstanding Teaching of First Year Students, 2011 Weithman 2. Teaching Recognition and Awards, cont'd. -

Life Divine Chapter XXIV: Spiritual Evolution of Man 1. Allegory of the Aeonic Visitor to Earth A. the Purpose Is Not Apparent T

Life Divine Chapter XXIV: Spiritual Evolution of Man 1. Allegory of the aeonic visitor to Earth A. The purpose is not apparent though might be perceived by a careful observer. 2. Man & Evolution A. Double Movement of Evolution . Evolution of Forms . Evolution of Consciousness . At each stage the form and consciousness have developed in harmony B. Science concludes life, mind and spirit are only forms of material activity . Like assuming electricity is a product of water and clouds because lightning occurs then . Energy of electricity is the foundation of energy substance . What seems to be a result is the cause C. Psychological progress of humanity is a fact – evolution in consciousness within the type D. Social evolution through three stages E. Appearance of human mind and body on earth marks a crucial step to conscious evolution F. Tradition assumes Mind is the last step . Tradition misses the teleology of creation 3. What is spiritual evolution? -- stages A. Action of spirit in our life B. Conscious experience of the touch of spirit on our being C. Discovery and realization of Spirit D. Ascent to Supermind and Supramental transformation of our Nature 4. Four needs and four aids to spiritual evolution A. Occultism . He must know himself and discover his potentialities 1 . Man must know his inner mental, vital, physical being and its powers and movements and the universal laws and processes of occult Mind and Life B. Religion – ethics . He must know the hidden Powers that control the world – the Cosmic Self or Spirit or Creator C. Philosophy – metaphysics . His thinking mind must know and accept the principles of things and observe the truth of the universe D. -

Economics: a Moral Inquiry with Religious Origins

American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 2011, 101:3, 166–170 http://www.aeaweb.org/articles.php?doi 10.1257/aer.101.3.166 = Economics: A Moral Inquiry with Religious Origins By Benjamin M. Friedman* Its secure foundation as an empirically based The commonplace view today is that the discipline notwithstanding, economics from its emergence of “economics” out of the European inception has also been a moral science. Adam Enlightenment of the eighteenth century was an Smith’s academic appointment was as profes- aspect of the more general movement toward sor of moral philosophy, and not only his earlier secular modernism in the sense of a historic turn Theory of Moral Sentiments but the Wealth of in thinking away from a God-centered universe, Nations, too, reflects it. Both books are replete toward what we broadly call humanism. To the with analyses of individuals’ motivations and contrary, I suggest that the all-important tran- psychological states, and the ways in which sition in thinking that we rightly identify with what we now call “economic” activity, carried Adam Smith and his contemporaries and follow- out in inherently social settings, enables them ers—the key transition that gave us economics as to lead satisfying lives or not. Even the divi- we now know it—was powerfully influenced by sion of labor, which Smith hailed from the then-controversial changes in religious belief in very first sentence of the Wealth of Nations( as the English-speaking Protestant world in which the key to enhanced productivity, is subject) to they lived. Further, those at-the-outset influences explicitly moral reservations—because it erodes of religious thinking not only fostered the subse- individuals’ capacities for “conceiving any gen- quent spread of Smithian thinking, especially in erous, noble or tender sentiment” and for judg- America, but shaped the course of its reception.