L-G-0010611093-0024726704.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Desires and Identity in Stella Gibbons's Gothic London By

Studies in Gothic Fiction • Volume 6 Issue 1 • 2018 © 4 “A Pleasure of that Too Intense Kind”: Women’s Desires and Identity in Stella Gibbons’s Gothic London by Rebecca Mills Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.18573/sgf.32 Copyright Rebecca Mills 2020 ISSN: 2156-2407 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Studies in Gothic Fiction • Volume 6 Issue 2 • 2020 © 5 Articles “A Pleasure of that Too Intense Kind”: Women’s Desires and Identity in Stella Gibbons’s Gothic London Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.18573/sgf.32 Rebecca Mills Abstract Stella Gibbons (1902-1989) is best known for the rural novel Cold Comfort Farm (1932), which Avril Horner and Sue Zlosnik discuss as “comic Gothic.” In contrast, Gibbons’s little-studied Hampstead novels Westwood (1946) and Here Be Dragons (1956) map a mel- ancholic Gothic fragmented city, marked by the Second World War, in which romantic attachment and marriage threaten young women’s comfort, self-sufficiency, and subjectivity. Excessive emotion and eroticism imperil women’s independence and identity, while the men they desire embody the temptation and corruption of the city. Gibbons employs Gothic language of spells, illusion, and entrapment to heighten anxieties around stifling domesticity and sacrificing the self for love. The London Gothic geogra- phies, atmosphere, and doubling of characters and spaces reinforce cautionary tales of the ill-effects of submission to love, while dedication to a career and community are offered as a means to resist Gothic desires and control Gothic spaces. -

John Guest Collection MS 4624 a Collection of Around 500 Personal

University Museums and Special Collections Service John Guest Collection MS 4624 A collection of around 500 personal and business letters from over 100 literary figures. They include 52 letters from Sir John Betjeman 1949-1979; 33 letters from Christopher Fry 1949-1989; 25 letters from Mary Renault 1960-1983, with further letters from her partner Julie Mullard and obituaries; 25 letters from Harold Nicolson 1949-1962; 17 letters from David Storey 1963-1994; 26 letters from Francis King 1950-1957, mainly concerning his British Council service in Greece; 12 letters from L.P. Hartley 1966-1970; 18 letters from William Plomer 1966-1972, mostly concerning the judging of the Cholmondeley Award for Poetry; 12 letters from Joan Hassall c.1954-1987; 12 letters from Laurence Whistler 1955-1986; 14 letters from A.N. Wilson 1979-1988, and 14 letters from Mary Wilson 1969-1986. Other correspondents include Rupert Hart-Davis, Christopher Hibbert, Mollie Hamilton (M.M. Kaye), Irene Handl, Stevie Smith, Stephen Spender and Muriel Spark. The Collection covers the year’s c. 1949-1991. The physical extent of the collection is c. 500 items. Introduction John Guest was born in 1911 in Warrington, Cheshire, and was educated at Fettes, Edinburgh, and Pembroke College, Cambridge. He was first employed in the publishing industry as a proofreader and subsequently junior editor for Collins, before serving in an artillery regiment during the war. In 1949 he was appointed literary advisor to the publishing firm Longmans, with a brief to rebuild their general trade list, at which he was very successful. He subsequently held the same position at Penguin Books, after the merger with Longmans in 1972, where he remained until his retirement. -

Catalogue 143 ~ Holiday 2008 Contents

Between the Covers - Rare Books, Inc. 112 Nicholson Rd (856) 456-8008 will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept Visa, MasterCard, American Express, Discover, and Gloucester City NJ 08030 Fax (856) 456-7675 PayPal. www.betweenthecovers.com [email protected] Domestic orders please include $5.00 postage for the first item, $2.00 for each item thereafter. Images are not to scale. All books are returnable within ten days if returned in Overseas orders will be sent airmail at cost (unless other arrange- the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. ments are requested). All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are Members ABAA, ILAB. unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions Cover verse and design by Tom Bloom © 2008 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. Catalogue 143 ~ Holiday 2008 Contents: ................................................................Page Literature (General Fiction & Non-Fiction) ...........................1 Baseball ................................................................................72 African-Americana ...............................................................55 Photography & Illustration ..................................................75 Children’s Books ..................................................................59 Music ...................................................................................80 -

Stella Gibbons, Ex-Centricity and the Suburb'

'Stella Gibbons, ex-centricity and the suburb' Outside the window, rows of little houses and gardens went past, with occasionally one of those little ruins that may be seen all up and down the railway lines of Greater London since the autumn of 1940, and in the blue sky the balloon barrage was anchored low above the roofs and gleamed pure silver in the evening light. The train was just leaving the suburbs and the barrage and entering the unprotected country. Shame, thought Alicia, who, like many other people, was rather fond of the balloons. - Stella Gibbons, The Bachelor (28) In The Intellectuals and the Masses (1992), John Carey writes: 'The rejection by intellectuals of the clerks and the suburbs meant that writers intent on finding an eccentric voice could do so by colonizing this abandoned territory. The two writers who did so were John Betjeman and Stevie Smith' (66). Whilst Carey's insight forms a useful starting point for this discussion, his restriction of the suburban literary terrain to just two writers must be disputed. Many other names should be added to the list, and one of the most important is Stella Gibbons, who wrote in - and about - the north London suburbs throughout her career. Her novels resist the easy assumption that suburban culture is unchallenging, intelligible, homogenous and highly conventional. Gibbons's fictional suburbs are socially and architecturally diverse, and her characters – who range from experimental writers to shopkeepers - read and interpret suburban styles and values in varying and incompatible ways. At times, she explores the traditional English ways of life which wealthy suburb dwellers long for and seek to recreate; at other times, she identifies the suburb with the future, with technology, innovation and evolving social structures. -

TLG to Big Reading

The Little Guide to Big Reading Talking BBC Big Read books with family, friends and colleagues Contents Introduction page 3 Setting up your own BBC Big Read book group page 4 Book groups at work page 7 Some ideas on what to talk about in your group page 9 The Top 21 page 10 The Top 100 page 20 Other ways to share BBC Big Read books page 26 What next? page 27 The Little Guide to Big Reading was created in collaboration with Booktrust 2 Introduction “I’ve voted for my best-loved book – what do I do now?” The BBC Big Read started with an open invitation for everyone to nominate a favourite book resulting in a list of the nation’s Top 100 books.It will finish by focusing on just 21 novels which matter to millions and give you the chance to vote for your favourite and decide the title of the nation’s best-loved book. This guide provides some ideas on ways to approach The Big Read and advice on: • setting up a Big Read book group • what to talk about and how to structure your meetings • finding other ways to share Big Read books Whether you’re reading by yourself or planning to start a reading group, you can plan your reading around The BBC Big Read and join the nation’s biggest ever book club! 3 Setting up your own BBC Big Read book group “Ours is a social group, really. I sometimes think the book’s just an extra excuse for us to get together once a month.” “I’ve learnt such a lot about literature from the people there.And I’ve read books I’d never have chosen for myself – a real consciousness raiser.” “I’m reading all the time now – and I’m not a reader.” Book groups can be very enjoyable and stimulating.There are tens of thousands of them in existence in the UK and each one is different. -

Children's Literature Peter Harrington

Peter Harrington Catalogue 87 Peter Harrington london CHILDREN’S LITERATURE 1 Catalogue 87 Index of names (references are to item numbers) Adams, Richard 1 Feilden, Helen Arbuthnot 50 Larson, Eric 47 Saville, Malcolm 206 Adamson, George 88 Ferguson, Norm 44 Laurencin, Marie 100 Schindelman, Joseph 33 Ainslie, Kathleen 2 Fitzgerald, Edward 56 Ledyard, Addie 29 Sears, Ted 44 Alcott, Louisa M. 3 Fitzgerald, Shafto Justin Adair 154 Leech, John 43 Sendak, Maurice 207–211 Andersen, Hans Christian 60, 127, 193 Fleming, Ian 66 Leigh, Howard 90 Seuss, Dr. 212–217 Anderson, Ken 47 Ford, H. J. 94–98 Leighton, Clare 101 Sewell, Anna 218 Arlen, Harold 13 Ford, Julia Ellsworth 171 Lewis, C. S. 102, 103, 104 Shakespeare, William 163, 175, 183 Ashley, Doris 4 Fortnum, Peggy 22 Liddell, Alice 51 Sharrocks, Burgess 20 Atenico, Xavier 47 Foster, Myles B. 73 Lloyd, R. J. 89 Shepard (later Knox), Mary 117, 244 Peter Harrington Attwell, Mabel Lucy 4 Frost, A. B. 79 Lofting, Hugh 105, 106 Shepard, E. H. 114–117, 119, 120, 219, 220 london Austin, Sarah 25 Gail, Otto Willi 67 Lounsbery, John 47 Sindall, Alfred 90 Awdry, Wilbert Vere 5, 6, 7 Galsworthy, Ada 10 Lucas, E. V. 219 Skinner, Ada M. & Eleanor M. 226 Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski de Rola) 8 Garner, Alan 68 Lucas, Mrs Edgar 165 Smith, Dodie 221 Bannerman, Helen 9 Geisel, Theodor 212–217 McCormick, A. D. 87 Smith, Jessie Wilcox 222–226 Barraud, George 123 Geromini, Gerry 47 Macfarlane, John 53 Smith, Paul J. 44 Barry, J. Arthur 156 Gibbons, Stella 69 Mackenzie, Thomas 107 Snicket, Lemony 227 Barrie, J. -

No Italian Translation

MASK OF BYRON DISPLAYS NEW FACE October 5, 2004 A WAX carnival mask worn by Lord Byron at the height of the great poet's passionate affair with a young Italian countess in the early 19th century goes on display in Rome today after a delicate restoration. The mask, worn by Byron at a Ravenna carnival in 1820, was given to the Keats-Shelley Memorial House 40 years ago. But Catherine Payling, 33, director of the museum, said she was shocked by its deterioration when taking over 15 months ago. The Keats-Shelley house, next to the Spanish Steps, where Keats died in 1821, contains memorabilia associated with Keats, Shelley and Byron, all of whom lived in Italy at the height of the Romantic movement. Byron had left England in 1816 after a series of affairs and a disastrous year-long marriage, to join a brilliant group of English literary exiles that included Shelley and his wife, Mary. In the spring of 1819, Byron met Countess Teresa Guiccioli, who was only 20 and had been married for a year to a rich and eccentric Ravenna aristocrat three times her age. The encounter, he said later, "changed my life", and from then on he confined himself to "only the strictest adultery". Byron gave up "light philandering" to live with Teresa, first in the Palazzo Guiccioli in Ravenna - conducting the affair under the nose of the count - and then in Pisa after the countess had obtained a separation by papal decree. In his letters to John Murray, his publisher, Byron said that carnivals and balls were "the best thing about Ravenna, when everybody runs mad for six weeks", and described wearing the mask - which originally sported a thick beard - to accompany the countess to the carnival. -

7Th August a Holiday Quiz in Four Parts: Part 1: the Booker Prize 1

7th August A holiday quiz in four parts: Part 1: The Booker Prize 1. Who won the first ever Booker prize? Name the author, title and year. 2. Who was the first woman to win the Booker prize in 1970 and what was the title of her novel? 3.The prize was shared by two authors last year but this has happened on two other occasions. Name the years in question and the four authors. 4. What is the longest winning novel in the prizes’ history? 5. What is the Booker Dozen? 6. Who won the special Golden Booker celebrating fifty years of the award and for which work? Answers 1. P H Newby. Something to Answer For . 1970. 2. Bernice Rubens. The Elected Member . 3. 1974. Stanley Middleton and Nadine Gordimer. 1992. Michael Ondaatje and Barry Unsworth. 4. The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton. 2013. 5. The longlist comprising thirteen novels. 6. Michael Ondaatje for The English Patient . Part 2: Poetry 1. Name the two poets who edited The Rattle Bag poetry anthology in 1982. 2. Which character in Dylan Thomas’ Under Milk Wood sings of loving Tom, Dick and Harry? 3. Who composed a symphony based on W.H. Auden’s The Age of Anxiety ? 4. Who dreamt about making a hot beverage for Kingsley Amis and what was the beverage? 5. Uccello’s painting Saint George and the Dragon (National Gallery) is the subject of which amusing poem by U.A. Fanthorpe? 6. In which two poems did John Betjeman refer to Highgate mansion flats? Name the poems and the flats. -

The Inter-War Middlebrow Novels of Em Delafield and Eh

‘THE BOOK HELD ME LIKE A VISIT FROM AN AMUSING, VALUED FRIEND’: THE INTER-WAR MIDDLEBROW NOVELS OF E. M. DELAFIELD AND E. H. YOUNG by KATHARINE ELIZABETH HOARE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY English College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis explores the perceived identification between reader and central character in a selection of E. M. Delafield’s and E. H. Young’s inter-war novels. These domestic middlebrow novels cleverly seduce the reader into believing that the world they are presented with in the book is real life. The authors mirrored their readers in the creation of their characters and so the reader is absorbed in an expertly contained and controlled aspirational fantasy. The authors encourage their reader’s identification with the characters in a variety of means which are examined through close textual analysis. A key source of information in this study comes from contemporary criticism, reviews and debate. -

"Impudent Scribblers": Place and the Unlikely Heroines of the Interwar Years

Perriam, Geraldine (2011) "Impudent scribblers": place and the unlikely heroines of the interwar years. PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2515/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] “Impudent Scribblers”: Place and the unlikely heroines of the interwar years Geraldine Perriam BEd, MEd, MRes, Dip. Teach. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Geographical and Earth Sciences Faculty of Law, Business and Social Sciences University of Glasgow Deposited in University Library on 18th April, 2011 ABSTRACT The central focus of this thesis is the storytelling of place and the place of storytelling. These elements comprise the geoliterary terrains of narrative, the cultural matrix in which texts are sited, produced and received, including the lifeworld of the author. The texts under scrutiny in this research have been written by women during the interwar years of the 20th Century in Britain and Australia. One of the primary aims of the thesis is to explore the geoliterary terrains (including the space known as the middlebrow) of these texts in light of their relative neglect by contemporary critics in comparison with the prominence given to works written by men during this period. -

January 2000

Hammill, F. (2001) Cold Comfort Farm, D. H. Lawrence, and English literary culture between the wars. MFS: Modern Fiction Studies, 47(4), pp. 831-854. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/148864/ Deposited on: 27 September 2017 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 Faye Hammill As published in Modern Fiction Studies 47.4 (Winter 2001)831-854. Cold Comfort Farm, DH Lawrence & English Literary Culture Between the Wars Stella Gibbons's Cold Comfort Farm (1932) has been an incredibly popular novel. Its most famous line, "I saw something nasty in the woodshed", has become a catchphrase, and the book has sold in large numbers during the whole period since its first publication in 1932. It has been adapted as a stage play, a musical, a radio drama and two films, thereby reaching a still larger audience.1 Its status within the academically-defined literary canon, by contrast, is low. One full article on Cold Comfort Farm was published in 1978, and since then, only a few paragraphs of criticism have been devoted to the novel. Critics are apparently reluctant to admit Cold Comfort Farm to be properly "literary", and it is rarely mentioned in studies of the literature of the interwar years. This is curious, because Cold Comfort Farm is an extremely sophisticated and intricate parody, whose meaning is produced through its relationship with the literary culture of its day, and with the work of such canonical authors as DH Lawrence, Thomas Hardy and Emily Bronte. -

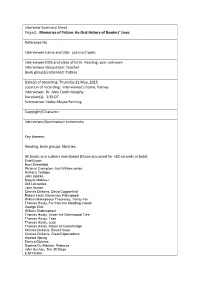

Interview Summary Sheet Project: Memories of Fiction: an Oral History of Readers’ Lives

Interview Summary Sheet Project: Memories of Fiction: An Oral History of Readers’ Lives Reference No. Interviewee name and title: Joanna Crooks Interviewee DOB and place of birth: Reading, year unknown. Interviewee Occupation: Teacher Book group(s) attended: Putney Date(s) of recording: Thursday 21 May, 2015 Location of recording: Interviewee’s home, Putney. Interviewer: Dr. Amy Tooth Murphy Duration(s): 1:35:07 Summariser: Haley Moyse Fenning Copyright/Clearance: Interviewer/Summariser comments: Key themes: Reading, book groups, libraries, All books and authors mentioned (those discussed for >20 seconds in bold): Enid Blyton Noel Streatfeild Richmal Crompton, Just William series Anthony Trollope John Updike Naguib Mahfouz Old Lob series Jane Austen Charles Dickens, David Copperfield Robert Louis Stevenson, Kidnapped William Makepeace Thackeray, Vanity Fair Thomas Hardy, Far from the Madding Crowd George Eliot William Shakespeare Thomas Hardy, Under the Greenwood Tree Thomas Hardy, Tess Thomas Hardy, Jude Thomas Hardy, Mayor of Casterbridge Charles Dickens, Bleak House Charles Dickens, Great Expectations Howard Spring Monica Dickens Daphne Du Maurier, Rebecca John Buchan, The 39 Steps E.M Forster James Joyce, Ulysees Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird William Golding, Lord of the Flies Alan Johnston, This Boy Philip Larkin Andrew Motion Evelyn Waugh John Le Carre, A Most Wanted Man Nicholas Monserrat, The Cruel Sea Noel Streatfield, The Ballet Shoes Lucy Maud Montgomery,