Freedom Rider Mary Hamilton, Page 19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, Day Department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 Points)

The elective discipline «INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, day department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 points) Task: Select one British folk ballad from the list below, write your name, perform your individual scientific research paper in writing according to the given scheme and hand your work in to the teacher: Titles of British Folk Ballads Students’ Surnames 1. № 58: “Sir Patrick Spens” 2. № 13: “Edward” 3. № 84: “Bonny Barbara Allen” 4. № 12: “Lord Randal” 5. № 169:“Johnie Armstrong” 6. № 243: “James Harris” / “The Daemon Lover” 7. № 173: “Mary Hamilton” 8. № 94: “Young Waters” 9. № 73:“Lord Thomas and Annet” 10. № 95:“The Maid Freed from Gallows” 11. № 162: “The Hunting of the Cheviot” 12. № 157 “Gude Wallace” 13. № 161: “The Battle of Otterburn” 14. № 54: “The Cherry-Tree Carol” 15. № 55: “The Carnal and the Crane” 16. № 65: “Lady Maisry” 17. № 77: “Sweet William's Ghost” 18. № 185: “Dick o the Cow” 19. № 186: “Kinmont Willie” 20. № 187: “Jock o the Side” 21. №192: “The Lochmaben Harper” 22. № 210: “Bonnie James Campbell” 23. № 37 “Thomas The Rhymer” 24. № 178: “Captain Car, or, Edom o Gordon” 25. № 275: “Get Up and Bar the Door” 26. № 278: “The Farmer's Curst Wife” 27. № 279: “The Jolly Beggar” 28. № 167: “Sir Andrew Barton” 29. № 286: “The Sweet Trinity” / “The Golden Vanity” 30. № 1: “Riddles Wisely Expounded” 31. № 31: “The Marriage of Sir Gawain” 32. № 154: “A True Tale of Robin Hood” N.B. You can find the text of the selected British folk ballad in the five-volume edition “The English and Scottish Popular Ballads: five volumes / [edited by Francis James Child]. -

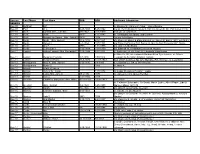

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P. m. Eleanor R. Clark 5-21-1866; stone illegible Bee-09 Purl J. C. 8-25-1898 5-25-1902 s/o Dr. Henry Bosworth & Laura Purl; b/o Aileen B. (Dr. Purl buried in CA) Bee-10 Buck Cynthia (Mrs. John #2) 2-6-1842 11-6-1930 2nd wife of John Buck Bee-10 Buck John 1807 3-25-1887 m.1st-Magdalena Spring; 2nd-Cynthia Bee-10 Buck Magdalena Spring (Mrs. John #1) 1805 1874 1st w/o John Buck Bee-10 Burris Ida B. (Mrs. James) 11-6-1858 2/12/1927 d/o Moses D. Burch & Efamia Beach; m. James R. Burris 1881; m/o Ora F. Bee-10 Burris James I. 5-7-1854 11/8/1921 s/o Robert & Pauline Rich Burris; m. Ida; f/o Son-Professor O.F. Burris Bee-10 Burris Ora F. 1886 2-11-1975 s/o James & Ida Burris Bee-10 Burris Zelma Ethel 7-15-1894 1-18-1959 d/o Elkanah W. & Mahala Ellen Smith Howard Bee-11 Lamkin Althea Leonard (Mrs. Benjamin F.) 7-15-1844 3/17/1931 b. Anderson, IN; d/o Samuel & Amanda Eads Brown b. Ohio Co, IN ; s/o Judson & Barbara Ellen Dyer Lamkin; m. Althea Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Franklin 1-7-1836 1/30/1914 Leonard; f/o Benjamin Franklin Lamkin Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Frank 11-9-1875 12-17-1943 Son of B.F. & Althea; Sp. Am. War Mo., Pvt. -

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers Moanin Mp3 Free

Art blakey and the jazz messengers moanin mp3 free Watch the video, get the download or listen to Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers – Moanin' for free. Moanin' appears on the album Moanin'. Before "soul" had. Art Blakey Amp Jazz Messengers Moanin MB · Moanin. Artist: Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers. ART BLAKEY amp THE JAZZ MESSENGERS MOANIN free download mp3. ART BLAKEY free downloads mp3 Free Music Downloads. Download Moanin art. Download Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers mp3. Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers download high quality complete mp3 albums. Buy the CD album for £ and get the MP3 version for FREE. Does not apply to gift orders. Provided by Amazon EU Sàrl. See Terms and Conditions for. not apply to gift orders. Complete your purchase to save the MP3 version to your music library. This item:Free For All by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers Audio CD $ In Stock. Ships from .. Moanin' Audio CD. Art Blakey and the. on orders over $25—or get FREE Two-Day Shipping with Amazon Prime. In Stock . This item:Moanin' [LP] by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers Vinyl $ Complete your purchase to save the MP3 version to your music library. This item's packaging may This item:Free for All [LP] by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers Vinyl $ In Stock. Ships from .. Moanin' Audio CD. Art Blakey and the. A new video, hope you like it and comment and rate! En la historia del jazz no abundan los baterías que dirigen grupos u orquestas; menos aun, los que han. Moanin' Album: Moanin' () Written by: Bobby Timmons Personnel: Art Blakey — drums Lee Morgan. -

English 577.02 Folklore 2: the Traditional Ballad (Tu/Th 9:35AM - 10:55AM; Hopkins Hall 246)

English 577.02 Folklore 2: The Traditional Ballad (Tu/Th 9:35AM - 10:55AM; Hopkins Hall 246) Instructor: Richard F. Green ([email protected]; phone: 292-6065) Office Hours: Wednesday 11:30 - 2:30 (Denney 529) Text: English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ed. F.J. Child, 5 vols (Cambridge, Mass.: 1882- 1898); available online at http://www.bluegrassmessengers.com/the-305-child-ballads.aspx.\ August Thurs 22 Introduction: “What is a Ballad?” Sources Tues 27 Introduction: Ballad Terminology: “The Gypsy Laddie” (Child 200) Thurs 29 “From Sir Eglamour of Artois to Old Bangum” (Child 18) September Tues 3 Movie: The Songcatcher Pt 1 Thurs 5 Movie: The Songcatcher Pt 2 Tues 10 Tragic Ballads Thurs 12 Twa Sisters (Child 10) Tues 17 Lord Thomas and Fair Annet (Child 73) Thurs 19 Romantic Ballads Tues 24 Young Bateman (Child 53) October Tues 1 Fair Annie (Child 62) Thurs 3 Supernatural Ballads Tues 8 Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight (Child 4) Thurs 10 Wife of Usher’s Well (Child 79) Tues 15 Religious Ballads Thurs 17 Cherry Tree Carol (Child 54) Tues 22 Bitter Withy Thurs 24 Historical & Border Ballads Tues 29 Sir Patrick Spens (Child 58) Thurs 31 Mary Hamilton (Child 173) November Tues 5 Outlaw & Pirate Ballads Thurs 7 Geordie (Child 209) Tues 12 Henry Martin (Child 250) Thurs 14 Humorous Ballads Tues 19 Our Goodman (Child 274) Thurs 21 The Farmer’s Curst Wife (Child 278) S6, S7, S8, S9, S23, S24) Tues 24 American Ballads Thurs 26 Stagolee, Jesse James, John Hardy Tues 28 Thanksgiving (PAPERS DUE) Jones, Omie Wise, Pretty Polly, &c. -

Freedom Riders Democracy in Action a Study Guide to Accompany the Film Freedom Riders Copyright © 2011 by WGBH Educational Foundation

DEMOCRACY IN ACTION A STUDY GUIDE TO ACCOMPANY THE FILM FREEDOM RIDERS DEMOCRACY IN ACTION A STUDY GUIDE TO ACCOMPANY THE FILM FREEDOM RIDERS Copyright © 2011 by WGBH Educational Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover art credits: Courtesy of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. Back cover art credits: Bettmann/CORBIS. To download a PDF of this guide free of charge, please visit www.facinghistory.org/freedomriders or www.pbs.org/freedomriders. ISBN-13: 978-0-9819543-9-4 ISBN-10: 0-9819543-9-1 Facing History and Ourselves Headquarters 16 Hurd Road Brookline, MA 02445-6919 ABOUT FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES Facing History and Ourselves is a nonprofit and the steps leading to the Holocaust—the educational organization whose mission is to most documented case of twentieth-century engage students of diverse backgrounds in an indifference, de-humanization, hatred, racism, examination of racism, prejudice, and antisemitism antisemitism, and mass murder. It goes on to in order to promote a more humane and explore difficult questions of judgment, memory, informed citizenry. As the name Facing History and legacy, and the necessity for responsible and Ourselves implies, the organization helps participation to prevent injustice. Facing History teachers and their students make the essential and Ourselves then returns to the theme of civic connections between history and the moral participation to examine stories of individuals, choices they confront in their own lives, and offers groups, and nations who have worked to build a framework and a vocabulary for analyzing the just and inclusive communities and whose stories meaning and responsibility of citizenship and the illuminate the courage, compassion, and political tools to recognize bigotry and indifference in their will that are needed to protect democracy today own worlds. -

A Collection of Ballads

A COLLECTION OF BALLADS INTRODUCTION When the learned first gave serious attention to popular ballads, from the time of Percy to that of Scott, they laboured under certain disabilities. The Comparative Method was scarcely understood, and was little practised. Editors were content to study the ballads of their own countryside, or, at most, of Great Britain. Teutonic and Northern parallels to our ballads were then adduced, as by Scott and Jamieson. It was later that the ballads of Europe, from the Faroes to Modern Greece, were compared with our own, with European Märchen, or children’s tales, and with the popular songs, dances, and traditions of classical and savage peoples. The results of this more recent comparison may be briefly stated. Poetry begins, as Aristotle says, in improvisation. Every man is his own poet, and, in moments of stronge motion, expresses himself in song. A typical example is the Song of Lamech in Genesis— “I have slain a man to my wounding, And a young man to my hurt.” Instances perpetually occur in the Sagas: Grettir, Egil, Skarphedin, are always singing. In Kidnapped, Mr. Stevenson introduces “The Song of the Sword of Alan,” a fine example of Celtic practice: words and air are beaten out together, in the heat of victory. In the same way, the women sang improvised dirges, like Helen; lullabies, like the lullaby of Danae in Simonides, and flower songs, as in modern Italy. Every function of life, war, agriculture, the chase, had its appropriate magical and mimetic dance and song, as in Finland, among Red Indians, and among Australian blacks. -

History, Ideology and Performance in Ian Brown's Mary and a Great

History, Ideology and Performance in Ian Brown’s Mary and A Great Reckonin’ Steve Cramer Ian Brown has, of course, written several plays on historical themes. In addition, and perhaps unusually for a playwright, he has also produced substantial critical writing on the uses of history on stage. At an early stage in his 1991 thesis, for example, Brown discusses the near impossibility of theatre as documentary history. In an analysis of the work of Peter Cheeseman at the Victoria Theatre, Stoke-on-Trent in the sixties, seventies and eighties, Brown cites the inevitable selectivity of the process of culling history directly from recorded historical sources. This is the case whether they are those of established historians or alternative histories to which those generally denied a voice on grounds such as class, race or gender contribute.1 Brown points out that whatever the source, the unavoidable process of ideological bias or auteurism must inevitably intrude upon the finished product. For all that, Brown as dramatist does not adopt an orthodox postmodernist position on history as something to be either ignored or fabulated into nostalgic pastiche for the sake of a present, ephemeral experience. Instead, he seeks to reappraise our accounts of history through a series of non-naturalistic tropes, intended to expose ideological imperatives in the semiotics of historical iconography. Brown’s Mary (1977)2 employs a succession of verfremdung techniques to create a continual distancing effect on his audience. Citing Peter Nichols’ The National Health (1970) among his influences, Brown states the intention of dislocating audience expectations through a series of parodic turns, never allowing his audience to settle with the comfortable mythologies of Mary, Queen of Scots. -

Ancient Scottish Ballads

Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2008 witii funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation in ftp ://www.arcli ive.org/details/anGientscottislibOOkinl l^^^<t^^tj<.^i)> / ^ i ANCIENT SCOTTISH BALLADS, UECOVEUED FROM TRADITION, AND NEVER BEFORE published: WITH NOTES, HISTORICAL AND EXPLANATORY: AND AN APPENDIX, (ITontainins t1)c airs of scbcval of t\]t JSnllatiB. Sum bethe of wcr, and sum of wo; And sum uf iuie, and mirthe also ; And sum of trccherie, and sum ofgilc; Of old aucntours that fcl wliilc. Lain le Frcyn. LONDON: LONGMAN, REES, ORME, BROWN, & GREEN, AND JOHN bTKVKNSON, EDINUUHGH. MDCi;CX.XVU TO ROBERT DUNDAS, ESQUIRE, OF ARNISTON, THIS VOLUME IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED VERY FAITHFUL AND OBEDIENT SERVANT, GEO. K. Kl NLOCH. il ^^^^ CONTENTS. 'i ^ ^ 1 i t ^^ ^ Prefatory Notice, ix /"*^ 1 rj Young Redin, 13 "t ' Earl Richard, p t -^"^ 25 . The Sheplierd's Dochter, /^S VOI* - Lord Lovel, 31 "l Johnie of Cocklesmuir, 36 1 /^•^'l Crnel Mother, 44 . ' Laird of VVariestoun, 49 "^ p»?T Laird of Blackwood, 58 The Wedding of Robin Hoo<l and Little John,.... G5 a1 S V.X •j t ' The Gardener, 74 \ I ,«! fl' Johnie Buneftan, 77 Lord Thomas of Winesberrie, 89 th p^q^Sweet Willie, 95 100 S fM6') Bonnie House of Airly, n "t 'Lord Donald, 107 Queen Jeanio, 116 Bonnie A nnio, 1 -^3 V.l :-: The Dukeof Atliol's Nourice, 127 A\s , 4 VIU "• p/oi; The Provost's Dochter, 131 I 5 Y') p. !<-! HyndeHorn, 135 ElfiaKnicht, 145 Young Peggy, 153 William Guiseman, 156 is Y'l f'K^ Laird of Ochiltree, 159 IS V-l p' /5- Laird of Lochnie, 167 The Duke of Athol, 170 Glasgow Peggy, 174 -=. -

The Jazz Messengers

The Jazz Messengers Steven Criado 2 décembre 2020 1 Introduction 1.1 Écoutes du 2 décembre 2020 — The Freedom Rider - Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (The Freedom Rider, enregistré en 61, sorti en 64) — United - Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (Roots & Herbs, enregistré en 61 pendant les sessions de Freedom Rider, sorti en 70) — Mr. Jin - Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (Indestructible, 1964) — I’m Not So Sure - Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (Anthenagin, 1973), écouter aussi la version de Roy Hargrove (Earfood, 2008) — Live des Jazz Messengers de 1974 au studio 104 de la Maison de la Radio (lien ci-dessous) — Witch Hunt - Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (Album of the Year, 1981) 2 Freedom riders — arrêt de la cour suprême qui interdit la ségrégation dans les transports, en contradiction avec la loi Jim Crow issue du code noir appliquée dans les états du sud — des militants prennent les bus inter-états en 61, un premier bus partant de Wahsington à la Nouvelle-Orléan, est arrêté dans l’Alabama, à Anniston. Pneu crevé, incendie provoqué par la foule, les militants qui s’échappent du bus sont battus, les blessés ont du quitter l’hôpital par crainte de représailles — l’enregistrement de l’album d’Art Blakey à lieu 3 semaines après 1 3 ANNÉES 70 ET 80 DES MESSENGERS 2 — civil right movement, mouvement des droits civiques formé dans les années 50 rassemblant toutes les organisations noires (N.A.A.C.P, Urban League, S.N.C.C., le C.O.R.E., S.C.L.C), poursuit la lutte contre la ségrégation raciale dans la loi américaine, accès à l’éducation, -

The Heraldry of the Hamiltons

era1 ^ ) of t fr National Library of Scotland *B000279526* THE Heraldry of the Ibamiltons NOTE 125 Copies of this Work have been printed, of which only 100 will be offered to the Public. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/heraldryofhamilsOOjohn PLATE I. THE theraldry of m Ibamiltons WITH NOTES ON ALL THE MALES OF THE FAMILY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE ARMS, PLATES AND PEDIGREES by G. HARVEY JOHNSTON F.S.A., SCOT. AUTHOR OF " SCOTTISH HERALDRY MADE EASY," ETC. *^3MS3&> W. & A. K. JOHNSTON, LIMITED EDINBURGH AND LONDON MCMIX WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR. circulation). 1. "THE RUDDIMANS" {for private 2. "Scottish Heraldry Made Easy." (out print). 3. "The Heraldry of the Johnstons" of {only a few copies remain). 4. "The Heraldry of the Stewarts" Douglases" (only a few copies remain). 5. "The Heraldry of the Preface. THE Hamiltons, so far as trustworthy evidence goes, cannot equal in descent either the Stewarts or Douglases, their history beginning about two hundred years later than that of the former, and one hundred years later than that of the latter ; still their antiquity is considerable. In the introduction to the first chapter I have dealt with the suggested earlier origin of the family. The Hamiltons were conspicuous in their loyalty to Queen Mary, and, judging by the number of marriages between members of the different branches, they were also loyal to their race. Throughout their history one hears little of the violent deeds which charac- terised the Stewarts and Douglases, and one may truthfully say the race has generally been a peaceful one. -

The Hard Bop Trombone: an Exploration of the Improvisational Styles of the Four Trombonist Who Defined the Genre (1955-1964)

The Hard Bop Trombone: An exploration of the improvisational styles of the four trombonist who defined the genre (1955-1964) Emmett C. Goods Dissertation submitted to the School of Music at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Trombone Performance H. Keith Jackson, DMA, Committee Chair Constinia Charbonnette, EDD David Taddie, Ph.D. Michael Vercelli, DMA Mitchell Arnold, DMA Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2019 Keywords: Hard Bop, Trombone, Jazz, Jazz Improvisation Copyright 2019 Emmett C. Goods The Hard Bop Trombone: An exploration of the improvisational styles of the four trombonist who defined the genre (1955-1964). Emmett C. Goods This dissertation examines the improvisational stylings of Curtis Fuller, Locksley “Slide” Hampton, Julian Priester and Grachan Moncur III from 1955 through 1964. In part one of this study, each musician is presented through their improvisational connections to J.J. Johnson, the leading trombonist of the Bebop era. His improvisational signatures are then traced through to the musical innovations of the Hard-Bop Trombone Era. Source material for this part of the study includes published books, dissertations, articles, online sources, discographies and personal interviews. Part two of this paper analyzes selected solos from each of the four subjects to identify the defining characteristics of the Hard-Bop Trombone Era. Evidence for these claims is bolstered by interviews conducted with the four men and their protégés. In a third and final part, a discography has been compiled for each artists during the defined era. Through historical analysis of these four artists’ music and recording of first-hand accounts from the artists themselves, this document attempts to properly contextualize the Hard-Bop Trombone Era as unique and important to the further development of the jazz trombone.