Truman Capote's in Cold Blood and the Origins of True Crime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Looking for Podcast Suggestions? We’Ve Got You Covered

Looking for podcast suggestions? We’ve got you covered. We asked Loomis faculty members to share their podcast playlists with us, and they offered a variety of suggestions as wide-ranging as their areas of personal interest and professional expertise. Here’s a collection of 85 of these free, downloadable audio shows for you to try, listed alphabetically with their “recommenders” listed below each entry: 30 for 30 You may be familiar with ESPN’s 30 for 30 series of award-winning sports documentaries on television. The podcasts of the same name are audio documentaries on similarly compelling subjects. Recent podcasts have looked at the man behind the Bikram Yoga fitness craze, racial activism by professional athletes, the origins of the hugely profitable Ultimate Fighting Championship, and the lasting legacy of the John Madden Football video game. Recommended by Elliott: “I love how it involves the culture of sports. You get an inner look on a sports story or event that you never really knew about. Brings real life and sports together in a fantastic way.” 99% Invisible From the podcast website: “Ever wonder how inflatable men came to be regular fixtures at used car lots? Curious about the origin of the fortune cookie? Want to know why Sigmund Freud opted for a couch over an armchair? 99% Invisible is about all the thought that goes into the things we don’t think about — the unnoticed architecture and design that shape our world.” Recommended by Scott ABCA Calls from the Clubhouse Interviews with coaches in the American Baseball Coaches Association Recommended by Donnie, who is head coach of varsity baseball and says the podcast covers “all aspects of baseball, culture, techniques, practices, strategy, etc. -

Teacher Notes

Media Series - TV Teacher Notes Television in the Global Age Teachers’ Notes The resources are intended to support teachers delivering on the new AS and A level specifications. They have been created based on the assumption that many teachers will already have some experience of teaching Media Studies and therefore have been pitched at a level which takes this into consideration. Other resources are readily available which outline e.g. technical and visual codes and how to apply these. There is overlap between the different areas of the theoretical framework and the various contexts, and a “text-out” teaching structure may offer opportunities for a more holistic approach. Slides are adaptable to use with your students. Explanatory notes for teachers/suggestions for teaching are in the Teachers’ Notes. The resources are intended to offer guidance only and are by no means exhaustive. It is expected that teachers will subsequently research and use their own materials and teaching strategies within their delivery. Television as an industry has changed dramatically since its inception. Digital technologies and other external factors have led to changes in production, distribution, the increasingly global nature of television and the ways in which audiences consume texts. It is expected that students will require teacher-led delivery which outlines these changes, but the focus of delivery will differ dependent on texts chosen. THE JINX: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst Episode Suggestions Episode 1 ‘The Body in the Bay’ is the ‘set’ text but you may also want to look at others, particularly Episode 6 with its “shocking” conclusion. -

INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, Day Department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 Points)

The elective discipline «INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, day department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 points) Task: Select one British folk ballad from the list below, write your name, perform your individual scientific research paper in writing according to the given scheme and hand your work in to the teacher: Titles of British Folk Ballads Students’ Surnames 1. № 58: “Sir Patrick Spens” 2. № 13: “Edward” 3. № 84: “Bonny Barbara Allen” 4. № 12: “Lord Randal” 5. № 169:“Johnie Armstrong” 6. № 243: “James Harris” / “The Daemon Lover” 7. № 173: “Mary Hamilton” 8. № 94: “Young Waters” 9. № 73:“Lord Thomas and Annet” 10. № 95:“The Maid Freed from Gallows” 11. № 162: “The Hunting of the Cheviot” 12. № 157 “Gude Wallace” 13. № 161: “The Battle of Otterburn” 14. № 54: “The Cherry-Tree Carol” 15. № 55: “The Carnal and the Crane” 16. № 65: “Lady Maisry” 17. № 77: “Sweet William's Ghost” 18. № 185: “Dick o the Cow” 19. № 186: “Kinmont Willie” 20. № 187: “Jock o the Side” 21. №192: “The Lochmaben Harper” 22. № 210: “Bonnie James Campbell” 23. № 37 “Thomas The Rhymer” 24. № 178: “Captain Car, or, Edom o Gordon” 25. № 275: “Get Up and Bar the Door” 26. № 278: “The Farmer's Curst Wife” 27. № 279: “The Jolly Beggar” 28. № 167: “Sir Andrew Barton” 29. № 286: “The Sweet Trinity” / “The Golden Vanity” 30. № 1: “Riddles Wisely Expounded” 31. № 31: “The Marriage of Sir Gawain” 32. № 154: “A True Tale of Robin Hood” N.B. You can find the text of the selected British folk ballad in the five-volume edition “The English and Scottish Popular Ballads: five volumes / [edited by Francis James Child]. -

Nancy Grace on Her Third Crimecon and Why She's Driven to Catch Criminals

DRIVEN BY JUSTICE Nancy Grace on Her Third CrimeCon and Why She’s Driven to Catch Criminals Perennial fan-favorite Nancy coming to a family reunion. Grace returns for her third The people who are here are CrimeCon, and she’s bringing all like me — dedicated to crime the fire, emotion, and endearing and crime sleuthing,” she told Southern colloquialisms we’ve the Indy Star during CrimeCon come to expect from the pint- 2017. “It’s very invigorating to be sized powerhouse. Grace has around people who share the become a staple of CrimeCon same interest and the natural weekend, often found taking curiosity that I have.” selfies with fans (“The angle is key,” she says) or laughing with Grace has dedicated most of podcasters on Podcast Row. her life to finding answers to the questions that drive our When she takes the stage at fascination with true crime. CrimeCon, though, she is all Her fans are familiar with the business. Grace is famous for story of Grace’s fiance, Keith, her impassioned rhetoric and who was gunned down in boundless energy, and she has his vehicle when Grace was no trouble rousing a crowd nineteen years old. His death -- and CrimeCon is exactly her sparked a change in Grace, kind of crowd. “It felt like I was who promptly switched gears, dropped her literature major, and began studying for law school. She earned a reputation as an outspoken and energetic prosecutor in Atlanta before becoming a broadcaster and crime commentator on HLN and other cable networks. “Wherever I can best do the work I’m called to do, that’s where I’ll go,” Grace told the CrimeCon Informant in 2017. -

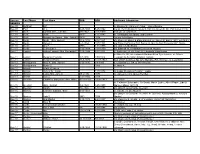

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P. m. Eleanor R. Clark 5-21-1866; stone illegible Bee-09 Purl J. C. 8-25-1898 5-25-1902 s/o Dr. Henry Bosworth & Laura Purl; b/o Aileen B. (Dr. Purl buried in CA) Bee-10 Buck Cynthia (Mrs. John #2) 2-6-1842 11-6-1930 2nd wife of John Buck Bee-10 Buck John 1807 3-25-1887 m.1st-Magdalena Spring; 2nd-Cynthia Bee-10 Buck Magdalena Spring (Mrs. John #1) 1805 1874 1st w/o John Buck Bee-10 Burris Ida B. (Mrs. James) 11-6-1858 2/12/1927 d/o Moses D. Burch & Efamia Beach; m. James R. Burris 1881; m/o Ora F. Bee-10 Burris James I. 5-7-1854 11/8/1921 s/o Robert & Pauline Rich Burris; m. Ida; f/o Son-Professor O.F. Burris Bee-10 Burris Ora F. 1886 2-11-1975 s/o James & Ida Burris Bee-10 Burris Zelma Ethel 7-15-1894 1-18-1959 d/o Elkanah W. & Mahala Ellen Smith Howard Bee-11 Lamkin Althea Leonard (Mrs. Benjamin F.) 7-15-1844 3/17/1931 b. Anderson, IN; d/o Samuel & Amanda Eads Brown b. Ohio Co, IN ; s/o Judson & Barbara Ellen Dyer Lamkin; m. Althea Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Franklin 1-7-1836 1/30/1914 Leonard; f/o Benjamin Franklin Lamkin Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Frank 11-9-1875 12-17-1943 Son of B.F. & Althea; Sp. Am. War Mo., Pvt. -

Medieval Ballads Instructor

Topic: Medieval Ballads Instructor: Mrs. Tincher Date: 26 Sept. 2011 Age Level: 17 to 18 yrs. Old English Level: English IV and Honors English IV Sources “The Ballad.” Grinnell College. Erik Simpson. 18 September 2011. Web. “Early Child Ballads.” PBM. Greg Lindahl. 18 September 2011. Web. Prentice Hall Literature: The British Tradition. Penguin Edition. 1 vol. New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc, 2007. Print. Rationale The NCSCoS requires that we explore British literature, and medieval ballads were an important part of the evolution of British literature. Also, studying ballads gives us, as readers, insight into the lives of those living in the medieval time period much like studying music from our own culture gives us insight into the workings of our own society. Focus & Review Journal: One hundred years from now a historian is given songs from today to analyze and learn how we lived as a society. What kinds of songs would they look at? What assumptions do you think the historian would make about our society? Do you think that the songs would give them a good idea of what life is like today? Objectives Students will understand the history and composition of ballads and how they relate to medieval history. NCSCoS Standards 1.02 Respond to texts so that the audience will: make connections between the learner's life and the text reflect on how cultural or historical perspectives may have influenced these responses 2.02 Analyze general principles at work in life and literature by: discovering and defining principles at work in personal experience and in literature. -

Judging the Suspect-Protagonist in True Crime Documentaries

Wesleyan University The Honors College Did He Do It?: Judging the Suspect-Protagonist in True Crime Documentaries by Paul Partridge Class of 2018 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors from the College of Film and the Moving Image Middletown, Connecticut April, 2018 Table of Contents Acknowledgments…………………………………...……………………….iv Introduction ...…………………………………………………………………1 Review of the Literature…………………………………………………………..3 Questioning Genre………………………………………………………………...9 The Argument of the Suspect-protagonist...…………………………………......11 1. Rise of a Genre……………………………………………………….17 New Ways of Investigating the Past……………………………………..19 Connections to Literary Antecedents…………………..………………...27 Shocks, Twists, and Observation……………………………..………….30 The Genre Takes Off: A Successful Marriage with the Binge-Watch Structure.........................................................................34 2. A Thin Blue Through-Line: Observing the Suspect-Protagonist Since Morris……………………………….40 Conflicts Crafted in Editing……………………………………………...41 Reveal of Delayed Information…………………………………………..54 Depictions of the Past…………………………………………………….61 3. Seriality in True Crime Documentary: Finding Success and Cultural Relevancy in the Binge- Watching Era…………………………………………………………69 Applying Television Structure…………………………………………...70 (De)construction of Innocence Through Long-Form Storytelling……….81 4. The Keepers: What Does it Keep, What Does ii It Change?..............................................................................................95 -

English 577.02 Folklore 2: the Traditional Ballad (Tu/Th 9:35AM - 10:55AM; Hopkins Hall 246)

English 577.02 Folklore 2: The Traditional Ballad (Tu/Th 9:35AM - 10:55AM; Hopkins Hall 246) Instructor: Richard F. Green ([email protected]; phone: 292-6065) Office Hours: Wednesday 11:30 - 2:30 (Denney 529) Text: English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ed. F.J. Child, 5 vols (Cambridge, Mass.: 1882- 1898); available online at http://www.bluegrassmessengers.com/the-305-child-ballads.aspx.\ August Thurs 22 Introduction: “What is a Ballad?” Sources Tues 27 Introduction: Ballad Terminology: “The Gypsy Laddie” (Child 200) Thurs 29 “From Sir Eglamour of Artois to Old Bangum” (Child 18) September Tues 3 Movie: The Songcatcher Pt 1 Thurs 5 Movie: The Songcatcher Pt 2 Tues 10 Tragic Ballads Thurs 12 Twa Sisters (Child 10) Tues 17 Lord Thomas and Fair Annet (Child 73) Thurs 19 Romantic Ballads Tues 24 Young Bateman (Child 53) October Tues 1 Fair Annie (Child 62) Thurs 3 Supernatural Ballads Tues 8 Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight (Child 4) Thurs 10 Wife of Usher’s Well (Child 79) Tues 15 Religious Ballads Thurs 17 Cherry Tree Carol (Child 54) Tues 22 Bitter Withy Thurs 24 Historical & Border Ballads Tues 29 Sir Patrick Spens (Child 58) Thurs 31 Mary Hamilton (Child 173) November Tues 5 Outlaw & Pirate Ballads Thurs 7 Geordie (Child 209) Tues 12 Henry Martin (Child 250) Thurs 14 Humorous Ballads Tues 19 Our Goodman (Child 274) Thurs 21 The Farmer’s Curst Wife (Child 278) S6, S7, S8, S9, S23, S24) Tues 24 American Ballads Thurs 26 Stagolee, Jesse James, John Hardy Tues 28 Thanksgiving (PAPERS DUE) Jones, Omie Wise, Pretty Polly, &c. -

Review of Capote's in Cold Blood

Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science Volume 1 Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science, Volume I, Spring Article 1 2013 5-2013 Review of Capote’s In Cold Blood Yevgeniy Mayba San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/themis Part of the American Literature Commons, Criminal Law Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Mayba, Yevgeniy (2013) "Review of Capote’s In Cold Blood," Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science: Vol. 1 , Article 1. https://doi.org/10.31979/THEMIS.2013.0101 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/themis/vol1/iss1/1 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Justice Studies at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science by an authorized editor of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Review of Capote’s In Cold Blood Keywords Truman Capote, In Cold Blood, book review This book review is available in Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/themis/vol1/iss1/1 Mayba: In Cold Blood Review 1 Review of Capote’s In Cold Blood Yevgeniy Mayba Masterfully combining fiction and journalism, Truman Capote delivers a riveting account of the senseless mass murder that occurred on November 15, 1959 in the quiet rural town of Holcomb, Kansas. Refusing to accept the inherent lack of suspense in his work, Capote builds the tension with the brilliant use of imagery and detailed exploration of the characters. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75-6523 HEMBREE, Charles William, 1939- NARRATIVE TECHNIQUE in the FICTION of EUDORA WELIY

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Learning Lineage and the Problem of Authenticity in Ozark Folk Music

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1-1-2020 Learning Lineage And The Problem Of Authenticity In Ozark Folk Music Kevin Lyle Tharp Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Recommended Citation Tharp, Kevin Lyle, "Learning Lineage And The Problem Of Authenticity In Ozark Folk Music" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1829. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1829 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEARNING LINEAGE AND THE PROBLEM OF AUTHENTICITY IN OZARK FOLK MUSIC A Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music The University of Mississippi by KEVIN L. THARP May 2020 Copyright Kevin L. Tharp 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Thorough examination of the existing research and the content of ballad and folk song collections reveals a lack of information regarding the methods by which folk musicians learn the music they perform. The centuries-old practice of folk song and ballad performance is well- documented. Many Child ballads and other folk songs have been passed down through the generations. Oral tradition is the principal method of transmission in Ozark folk music. The variants this method produces are considered evidence of authenticity. Although alteration is a distinguishing characteristic of songs passed down in the oral tradition, many ballad variants have persisted in the folk record for great lengths of time without being altered beyond recognition. -

The Creighton-Senior Collaboration, 1932-51

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Athabasca University Library Institutional Repository The Creighton-Senior Collaboration, 1932-51 The arrival of Doreen Senior in Halifax in the book, and she was looking for a new collaborator summer of 1932 was a fortuitous event for Canadian who could note the melodies while she wrote down folksong collecting. Doreen, a friend and disciple of the words. In her autobiography, A Life in Folklore, Maud Karpeles, was a folk and country dance she recalled her first meeting with Doreen in the instructor, trained by the English Folk Dance Society, following terms: who anticipated a career as a music teacher making good use of Cecil Sharp's published collections of For years the Nova Scotia Summer School had Folk Songs for Schools. She was aware that Maud been bringing interesting people here, and one day I was invited to meet a new teacher, Miss had recently undertaken two successful collecting Doreen Senior of the English Folk Song and trips to Newfoundland (in 1929 and 1930), and was Dance Society. She liked people and they liked curious to see if Nova Scotia might similarly afford her to such an extent that whenever I met one of interesting variants of old English folksongs and her old summer school students in later years, ballads, or even songs that had crossed the Atlantic they would always ask about her. She was a and subsequently disappeared in their more urban and musician with the gift of perfect pitch and she industrialized land of origin.