History, Ideology and Performance in Ian Brown's Mary and a Great

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, Day Department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 Points)

The elective discipline «INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, day department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 points) Task: Select one British folk ballad from the list below, write your name, perform your individual scientific research paper in writing according to the given scheme and hand your work in to the teacher: Titles of British Folk Ballads Students’ Surnames 1. № 58: “Sir Patrick Spens” 2. № 13: “Edward” 3. № 84: “Bonny Barbara Allen” 4. № 12: “Lord Randal” 5. № 169:“Johnie Armstrong” 6. № 243: “James Harris” / “The Daemon Lover” 7. № 173: “Mary Hamilton” 8. № 94: “Young Waters” 9. № 73:“Lord Thomas and Annet” 10. № 95:“The Maid Freed from Gallows” 11. № 162: “The Hunting of the Cheviot” 12. № 157 “Gude Wallace” 13. № 161: “The Battle of Otterburn” 14. № 54: “The Cherry-Tree Carol” 15. № 55: “The Carnal and the Crane” 16. № 65: “Lady Maisry” 17. № 77: “Sweet William's Ghost” 18. № 185: “Dick o the Cow” 19. № 186: “Kinmont Willie” 20. № 187: “Jock o the Side” 21. №192: “The Lochmaben Harper” 22. № 210: “Bonnie James Campbell” 23. № 37 “Thomas The Rhymer” 24. № 178: “Captain Car, or, Edom o Gordon” 25. № 275: “Get Up and Bar the Door” 26. № 278: “The Farmer's Curst Wife” 27. № 279: “The Jolly Beggar” 28. № 167: “Sir Andrew Barton” 29. № 286: “The Sweet Trinity” / “The Golden Vanity” 30. № 1: “Riddles Wisely Expounded” 31. № 31: “The Marriage of Sir Gawain” 32. № 154: “A True Tale of Robin Hood” N.B. You can find the text of the selected British folk ballad in the five-volume edition “The English and Scottish Popular Ballads: five volumes / [edited by Francis James Child]. -

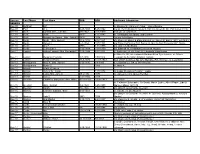

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P. m. Eleanor R. Clark 5-21-1866; stone illegible Bee-09 Purl J. C. 8-25-1898 5-25-1902 s/o Dr. Henry Bosworth & Laura Purl; b/o Aileen B. (Dr. Purl buried in CA) Bee-10 Buck Cynthia (Mrs. John #2) 2-6-1842 11-6-1930 2nd wife of John Buck Bee-10 Buck John 1807 3-25-1887 m.1st-Magdalena Spring; 2nd-Cynthia Bee-10 Buck Magdalena Spring (Mrs. John #1) 1805 1874 1st w/o John Buck Bee-10 Burris Ida B. (Mrs. James) 11-6-1858 2/12/1927 d/o Moses D. Burch & Efamia Beach; m. James R. Burris 1881; m/o Ora F. Bee-10 Burris James I. 5-7-1854 11/8/1921 s/o Robert & Pauline Rich Burris; m. Ida; f/o Son-Professor O.F. Burris Bee-10 Burris Ora F. 1886 2-11-1975 s/o James & Ida Burris Bee-10 Burris Zelma Ethel 7-15-1894 1-18-1959 d/o Elkanah W. & Mahala Ellen Smith Howard Bee-11 Lamkin Althea Leonard (Mrs. Benjamin F.) 7-15-1844 3/17/1931 b. Anderson, IN; d/o Samuel & Amanda Eads Brown b. Ohio Co, IN ; s/o Judson & Barbara Ellen Dyer Lamkin; m. Althea Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Franklin 1-7-1836 1/30/1914 Leonard; f/o Benjamin Franklin Lamkin Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Frank 11-9-1875 12-17-1943 Son of B.F. & Althea; Sp. Am. War Mo., Pvt. -

English 577.02 Folklore 2: the Traditional Ballad (Tu/Th 9:35AM - 10:55AM; Hopkins Hall 246)

English 577.02 Folklore 2: The Traditional Ballad (Tu/Th 9:35AM - 10:55AM; Hopkins Hall 246) Instructor: Richard F. Green ([email protected]; phone: 292-6065) Office Hours: Wednesday 11:30 - 2:30 (Denney 529) Text: English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ed. F.J. Child, 5 vols (Cambridge, Mass.: 1882- 1898); available online at http://www.bluegrassmessengers.com/the-305-child-ballads.aspx.\ August Thurs 22 Introduction: “What is a Ballad?” Sources Tues 27 Introduction: Ballad Terminology: “The Gypsy Laddie” (Child 200) Thurs 29 “From Sir Eglamour of Artois to Old Bangum” (Child 18) September Tues 3 Movie: The Songcatcher Pt 1 Thurs 5 Movie: The Songcatcher Pt 2 Tues 10 Tragic Ballads Thurs 12 Twa Sisters (Child 10) Tues 17 Lord Thomas and Fair Annet (Child 73) Thurs 19 Romantic Ballads Tues 24 Young Bateman (Child 53) October Tues 1 Fair Annie (Child 62) Thurs 3 Supernatural Ballads Tues 8 Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight (Child 4) Thurs 10 Wife of Usher’s Well (Child 79) Tues 15 Religious Ballads Thurs 17 Cherry Tree Carol (Child 54) Tues 22 Bitter Withy Thurs 24 Historical & Border Ballads Tues 29 Sir Patrick Spens (Child 58) Thurs 31 Mary Hamilton (Child 173) November Tues 5 Outlaw & Pirate Ballads Thurs 7 Geordie (Child 209) Tues 12 Henry Martin (Child 250) Thurs 14 Humorous Ballads Tues 19 Our Goodman (Child 274) Thurs 21 The Farmer’s Curst Wife (Child 278) S6, S7, S8, S9, S23, S24) Tues 24 American Ballads Thurs 26 Stagolee, Jesse James, John Hardy Tues 28 Thanksgiving (PAPERS DUE) Jones, Omie Wise, Pretty Polly, &c. -

A Collection of Ballads

A COLLECTION OF BALLADS INTRODUCTION When the learned first gave serious attention to popular ballads, from the time of Percy to that of Scott, they laboured under certain disabilities. The Comparative Method was scarcely understood, and was little practised. Editors were content to study the ballads of their own countryside, or, at most, of Great Britain. Teutonic and Northern parallels to our ballads were then adduced, as by Scott and Jamieson. It was later that the ballads of Europe, from the Faroes to Modern Greece, were compared with our own, with European Märchen, or children’s tales, and with the popular songs, dances, and traditions of classical and savage peoples. The results of this more recent comparison may be briefly stated. Poetry begins, as Aristotle says, in improvisation. Every man is his own poet, and, in moments of stronge motion, expresses himself in song. A typical example is the Song of Lamech in Genesis— “I have slain a man to my wounding, And a young man to my hurt.” Instances perpetually occur in the Sagas: Grettir, Egil, Skarphedin, are always singing. In Kidnapped, Mr. Stevenson introduces “The Song of the Sword of Alan,” a fine example of Celtic practice: words and air are beaten out together, in the heat of victory. In the same way, the women sang improvised dirges, like Helen; lullabies, like the lullaby of Danae in Simonides, and flower songs, as in modern Italy. Every function of life, war, agriculture, the chase, had its appropriate magical and mimetic dance and song, as in Finland, among Red Indians, and among Australian blacks. -

Ancient Scottish Ballads

Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2008 witii funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation in ftp ://www.arcli ive.org/details/anGientscottislibOOkinl l^^^<t^^tj<.^i)> / ^ i ANCIENT SCOTTISH BALLADS, UECOVEUED FROM TRADITION, AND NEVER BEFORE published: WITH NOTES, HISTORICAL AND EXPLANATORY: AND AN APPENDIX, (ITontainins t1)c airs of scbcval of t\]t JSnllatiB. Sum bethe of wcr, and sum of wo; And sum uf iuie, and mirthe also ; And sum of trccherie, and sum ofgilc; Of old aucntours that fcl wliilc. Lain le Frcyn. LONDON: LONGMAN, REES, ORME, BROWN, & GREEN, AND JOHN bTKVKNSON, EDINUUHGH. MDCi;CX.XVU TO ROBERT DUNDAS, ESQUIRE, OF ARNISTON, THIS VOLUME IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED VERY FAITHFUL AND OBEDIENT SERVANT, GEO. K. Kl NLOCH. il ^^^^ CONTENTS. 'i ^ ^ 1 i t ^^ ^ Prefatory Notice, ix /"*^ 1 rj Young Redin, 13 "t ' Earl Richard, p t -^"^ 25 . The Sheplierd's Dochter, /^S VOI* - Lord Lovel, 31 "l Johnie of Cocklesmuir, 36 1 /^•^'l Crnel Mother, 44 . ' Laird of VVariestoun, 49 "^ p»?T Laird of Blackwood, 58 The Wedding of Robin Hoo<l and Little John,.... G5 a1 S V.X •j t ' The Gardener, 74 \ I ,«! fl' Johnie Buneftan, 77 Lord Thomas of Winesberrie, 89 th p^q^Sweet Willie, 95 100 S fM6') Bonnie House of Airly, n "t 'Lord Donald, 107 Queen Jeanio, 116 Bonnie A nnio, 1 -^3 V.l :-: The Dukeof Atliol's Nourice, 127 A\s , 4 VIU "• p/oi; The Provost's Dochter, 131 I 5 Y') p. !<-! HyndeHorn, 135 ElfiaKnicht, 145 Young Peggy, 153 William Guiseman, 156 is Y'l f'K^ Laird of Ochiltree, 159 IS V-l p' /5- Laird of Lochnie, 167 The Duke of Athol, 170 Glasgow Peggy, 174 -=. -

The Heraldry of the Hamiltons

era1 ^ ) of t fr National Library of Scotland *B000279526* THE Heraldry of the Ibamiltons NOTE 125 Copies of this Work have been printed, of which only 100 will be offered to the Public. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/heraldryofhamilsOOjohn PLATE I. THE theraldry of m Ibamiltons WITH NOTES ON ALL THE MALES OF THE FAMILY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE ARMS, PLATES AND PEDIGREES by G. HARVEY JOHNSTON F.S.A., SCOT. AUTHOR OF " SCOTTISH HERALDRY MADE EASY," ETC. *^3MS3&> W. & A. K. JOHNSTON, LIMITED EDINBURGH AND LONDON MCMIX WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR. circulation). 1. "THE RUDDIMANS" {for private 2. "Scottish Heraldry Made Easy." (out print). 3. "The Heraldry of the Johnstons" of {only a few copies remain). 4. "The Heraldry of the Stewarts" Douglases" (only a few copies remain). 5. "The Heraldry of the Preface. THE Hamiltons, so far as trustworthy evidence goes, cannot equal in descent either the Stewarts or Douglases, their history beginning about two hundred years later than that of the former, and one hundred years later than that of the latter ; still their antiquity is considerable. In the introduction to the first chapter I have dealt with the suggested earlier origin of the family. The Hamiltons were conspicuous in their loyalty to Queen Mary, and, judging by the number of marriages between members of the different branches, they were also loyal to their race. Throughout their history one hears little of the violent deeds which charac- terised the Stewarts and Douglases, and one may truthfully say the race has generally been a peaceful one. -

Freedom Rider Mary Hamilton, Page 19

Mary Hamilton, Louise Inghram, and others 25c " My stay in Jacksoll ... made my going 01/ a Freedom Ride worthwhile." -freedom Rider Mary Hamilton, page 19 " I belong to a generation which WOIl't live with segregatioll . " - Freedom Rider Robert, poge 46 " Civil Rights is the name of Freedom in this country. " - Freedom Rider Louise Inghram, poge 60 Pictured on Front Cover: FREEDOM RIDERS who were arreste d at a bus station. in Jo,kson, Mississippi, early on May 28, 196', walk to the patrol wogon ofter their arrest. (Wide Wor ld) A News & I.elle,s Pamphlel Published by News & Letters, 8751 Grand River, Dctroit 4, Michigon November, 1961 2 1 Jackson, Mississippi, U. S. A. Freedom Rider Mary Hamilton: We pulled into the Jackson station, Sunday morning, at 10:15. Everything was deadly still. Police were posted all over-outside J the station, and inside the terminal. There were a few people standing around watching us. We walked very quietly through the Negro waiting room, and into the white waiting room. Some of the people took seats. Police Captain J. L. Ray was there, and reporters, and plain clothesmen, and many policemen. Captain Ray walked up and said, "Who's the spokesman for this group?" We pointed out the spokesman. He said, "Are you all going to move on?" OUf spokesman said, "Why must we move on?" Captain Ray said, "I said are you all going to move on? Move on, and move out of this here station." Our spokesman said, "We're interstate travelers. What reason is there for us to leave the station?" And he said again, he was very angry, "I said you all move on and leave this here station." Our spokesman said, "No. -

Controlling Women: "Reading Gender in the Ballads Scottish Women Sang" Author(S): Lynn Wollstadt Source: Western Folklore, Vol

Controlling Women: "Reading Gender in the Ballads Scottish Women Sang" Author(s): Lynn Wollstadt Source: Western Folklore, Vol. 61, No. 3/4 (Autumn, 2002), pp. 295-317 Published by: Western States Folklore Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1500424 . Accessed: 09/04/2013 10:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Western States Folklore Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Western Folklore. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 143.107.8.10 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 10:20:12 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ControllingWomen ReadingGender in theBallads ScottishWomen Sang LYNN WOLLSTADT The Scottishballad traditionhas alwaysbeen a traditionof both sexes; since ballads startedto be collected in the eighteenthcentury, at least, both men and women have learned and passed on these traditional songs.1According to the recordingsmade of traditionalsingers by the School of ScottishStudies at the Universityof Edinburgh,however, men and women do not necessarilysing the same songs.The ten songsin the School's sound archives most often recorded from female singers between 1951 and 1997, for example, have only two titlesin common withthe ten songs mostoften recorded frommen.2 Analysis of the spe- cificballad narrativesthat were most popular among female singersin twentieth-centuryScotland suggestscertain buried themes that may underlie that popularity;these particularthemes may have appealed more than othersto manywomen singers. -

English 577.02 Folklore 2

English 577.02 Folklore 2: The Traditional Ballad This course will study development of the traditonal folk ballad from its origins in the European Middle Ages down to its continuing presence in contemporary North America. The primary focus will be thematic (Tragic Ballads, Supernatural Ballads, Outlaw Ballads, Humorous Ballads, etc), but there will some opportunity to discuss the traditional ballad in relation to related types like the broadside, and the literary ballad. There will be a strong emphasis upon the ballad in performance throughout, and wherever possible ballad tunes will also be included. Text: English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ed. F.J. Child (Cambridge edition); available from Long’s or at http://www.zippublishing.com/CoursesWi04/English577.html Assignments: 1 presentation (25); 1 paper (30); 1 final exam (30). participation and attendance: (15). Except for the north-american ballads (week 10), the presentations will be given in pairs: two students will be expected to introduce the class to two different versions of the same ballad (wherever possible, one from the British Isles and the other from North America). Any student who so chooses may sing a ballad before the class instead of giving a presentation. Jan 6 Introduction 8 “The Gypsy Laddie” Jan 13 Tragic Ballads 15 presentations: “Lamkin”; “Clerk Saunders” Jan 20 Romantic Ballads 22 presentations: “Barbara Allen”; “Young Bateman” Jan 27 Supernatural Ballads 29 presentations: “Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight”; “TheWife of Usher’s Well” Feb 3 Religious Ballads 5 presentations: -

Singlish Song Book 25

Banana Boat Song Both Sides Now Battle of ‘Astings Ca' the Ewes Battle of New Orleans Delaney’s Donkey ‘S inglish Folk’ Bear Went Over the Mountain D-Day Dodgers Biddy Mulligan Deep River Blacksmith Courted Me East Virginia B roadsheet Blood Red Roses Geordie Blow ye winds Guantanamera Knocker-Up GNeorudie mber 25 Mary Hamilton Geordie Mary Hamilton Michael Finnegan Spinning Wheel 1. As I came over London bridge Word is to the kitchen gone One misty morning early and word is to the hall, I overheard a fair pretty maid And word is up to Madam the Queen Lamenting for her Geordie and that is the worst of all. That Mary Hamilton's born a child, 2. Come bridle me my silk white steed to the highest Stuart of all. Come bridle me my pony That I may ride to fair London town "Arise,arise Mary Hamilton, To plead for the life of Geordie Arise and tell to me, What hast thou done with thy wee baby 3. And when she entered in the hall I heard and I saw weep by thee ?" There were Lords and Ladies plenty Down on her bended knee she fell "I put him in a tiny boat, To plead for the life of Geordie and cast him out to sea, That he might sink or he might swim, 4. Oh Geordie stole nor cow nor calf but he'd never come back to me." Nor sheep he ne’er stole any But he stole sixteen of the king’s wild deer "Arise, arise Mary Hamilton, And sold them in Bohenny Arise and come with me; There is a wedding in Glasgow town, 5. -

I He Norton Anthology Or Poetry FOURTH EDITION

I he Norton Anthology or Poetry FOURTH EDITION •••••••••••< .•' .'.•.;';;/';•:; Margaret Ferguson > . ' COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY >':•! ;•/.'.'":•:;•> Mary Jo Salter MOUNT HOLYOKE COLLEGE Jon Stallworthy OXFORD UNIVERSITY W. W. NORTON & COMPANY • New York • London Contents PREFACE TO THE FOURTH EDITION lv Editorial Procedures ' Ivi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS " lix VERSIFICATION lxi Rhythm lxii Meter lxii Rhyme lxix Forms Ixxi Basic Forms Ixxi Composite Forms lxxvi Irregular Forms Ixxvii Open Forms or Free Verse lxxviii Further Reading lxxx GEDMON'S HYMN (translated by John Pope) 1 FROM BEOWULF (translated by Edwin Morgan) 2 RIDDLES (translated by Richard Hamer) 7 1 ("I am a lonely being, scarred by swords") 7 2 ("My dress is silent when I tread the ground") 8 3 ("A moth ate words; a marvellous event") 8 THE WIFE'S LAMENT (translated by Richard Hamer) 8 THE SEAFARER (translated by Richard Hamer) 10 ANONYMOUS LYRICS OF THE THIRTEENTH AND FOURTEENTH CENTURIES 13 Now Go'th Sun Under Wood 13 The Cuckoo Song 13 Ubi Sunt Qui Ante Nos Fuerunt? 13 Alison 15 Fowls in the Frith 16 • I Am of Ireland 16 GEOFFREY CHAUCER (ca. 1343-1400) 17 THE CANTERBURY TALES 17 The General Prologue 17 The Pardoner's Prologue and Tale 37 The Introduction 37 The Prologue 38 VI • CONTENTS The Tale 41 The Epilogue 50 From Troilus and Criseide 52 Cantus Troili 52 LYRICS AND OCCASIONAL VERSE 52 To Rosamond 52 Truth 53 Complaint to His Purse 54 To His Scribe Adam 5 5 PEARL, 1-5 (1375-1400) 55 WILLIAM LANGLAND(fl. 1375) 58 Piers Plowman, lines 1-111 58 CHARLES D'ORLEANS (1391-1465) 62 The Smiling Mouth 62 Oft in My Thought 62 ANONYMOUS LYRICS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY 63 Adam Lay I-bounden 63 I Sing of a Maiden 63 Out of Your Sleep Arise and Wake 64 I Have a Young Sister 65 I Have a Gentle Cock 66 Timor Mortis 66 The Corpus Christi Carol 67 Western Wind 68 A Lyke-Wake Dirge 68 A Carol of Agincourt 69 The Sacrament of the Altar 70 See! here, my heart 70 WILLIAM DUNBAR (ca. -

Truman Capote's in Cold Blood and the Origins of True Crime

Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and the Origins of True Crime By Harold Schechter 1. An early Wikipedia entry on “true crime” identified the 1965 publication of In Cold Blood as the origin of the genre, a wildly inaccurate assertion that has since been corrected. In point of fact, true crime literature extends back several centuries B. C.-- Before Capote, that is. At least as far back as the early Renaissance, tragic tales of murder, lust, and betrayal were made into songs and transmitted orally for the benefit of illiterate peasants. Many of these ballads were later transcribed by folklore scholars. Of the eight examples of English ballads reprinted in the standard college textbook, The Norton Anthology of Poetry, one describes a father brutally slain by his daughter’s new husband, who is fatally wounded in the struggle (“The Daughter’s Tragedy”); one deals with a young man poisoned by his lover (“Lord Randall”); one involves a woman who is hanged for the murder of her illegitimate child (“Mary Hamilton”); one relates the conversation among a trio of carrion birds as they contemplate the bloody remains of a murdered knight (“The Three Ravens”); and one concerns necrophilia (“The Unquiet Grave”). By Shakespeare’s time, traveling peddlers had figured out a way to profit from the public’s love of sensationalism by selling printed versions of popular ballads. Some of these were the Elizabethan equivalent of supermarket tabloids, providing news of strange and shocking events, many of dubious authenticity. “A Marvelous Occurrence, Being the True Relation of the Raining of Wheat in Yorkshire” and “The True Report of a Monstrous Pig which was Farrowed at Hamstead” are typical titles from the late sixteenth century.