Folk Songs in Ontario

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, Day Department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 Points)

The elective discipline «INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, day department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 points) Task: Select one British folk ballad from the list below, write your name, perform your individual scientific research paper in writing according to the given scheme and hand your work in to the teacher: Titles of British Folk Ballads Students’ Surnames 1. № 58: “Sir Patrick Spens” 2. № 13: “Edward” 3. № 84: “Bonny Barbara Allen” 4. № 12: “Lord Randal” 5. № 169:“Johnie Armstrong” 6. № 243: “James Harris” / “The Daemon Lover” 7. № 173: “Mary Hamilton” 8. № 94: “Young Waters” 9. № 73:“Lord Thomas and Annet” 10. № 95:“The Maid Freed from Gallows” 11. № 162: “The Hunting of the Cheviot” 12. № 157 “Gude Wallace” 13. № 161: “The Battle of Otterburn” 14. № 54: “The Cherry-Tree Carol” 15. № 55: “The Carnal and the Crane” 16. № 65: “Lady Maisry” 17. № 77: “Sweet William's Ghost” 18. № 185: “Dick o the Cow” 19. № 186: “Kinmont Willie” 20. № 187: “Jock o the Side” 21. №192: “The Lochmaben Harper” 22. № 210: “Bonnie James Campbell” 23. № 37 “Thomas The Rhymer” 24. № 178: “Captain Car, or, Edom o Gordon” 25. № 275: “Get Up and Bar the Door” 26. № 278: “The Farmer's Curst Wife” 27. № 279: “The Jolly Beggar” 28. № 167: “Sir Andrew Barton” 29. № 286: “The Sweet Trinity” / “The Golden Vanity” 30. № 1: “Riddles Wisely Expounded” 31. № 31: “The Marriage of Sir Gawain” 32. № 154: “A True Tale of Robin Hood” N.B. You can find the text of the selected British folk ballad in the five-volume edition “The English and Scottish Popular Ballads: five volumes / [edited by Francis James Child]. -

Popular Ballads /1

Popular Ballads /1 POPULAR BALLADS Ballads are anonymous narrative songs that have been preserved by oral transmission. Although any stage of a given culture may produce ballads, they are most character- istic of primitive societies such as that of the American frontier in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries or that of the English-Scottish border region in the later Middle Ages. These northern English songs, even divorced from the tunes to which they were once sung, are narrative poems of great literary interest. The origins of the popular (or folk) ballad are much disputed. The theory that they were first composed by communal effort, taking shape as the songs with which prim- itive people accompanied ritual dances, no longer seems plausible. On the other hand, the forms in which the ballads have come down to us show that they have been subjected to a continuing process of revision, both conscious and unconscious, by those through whose lips and memories they passed. Though the English ballads were probably composed during the five-hundred-year period from 1200 to 1700, few of them were printed before the eighteenth century and some not until the nineteenth. Bishop Thomas Percy (1729–1811) was among the first to take a literary interest in ballads, stimulated by his chance discovery of a seventeenth-century manuscript in which a number of them had been copied down among a great welter of Middle English verse. Percy’s publication of this material in his Reliques of Ancient English Poetry inspired others, notably Sir Walter Scott, to go to the living source of the ballads and to set them down on paper at the dictation of the border people among whom the old songs were still being sung. -

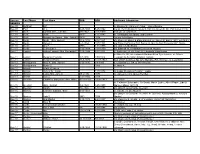

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P. m. Eleanor R. Clark 5-21-1866; stone illegible Bee-09 Purl J. C. 8-25-1898 5-25-1902 s/o Dr. Henry Bosworth & Laura Purl; b/o Aileen B. (Dr. Purl buried in CA) Bee-10 Buck Cynthia (Mrs. John #2) 2-6-1842 11-6-1930 2nd wife of John Buck Bee-10 Buck John 1807 3-25-1887 m.1st-Magdalena Spring; 2nd-Cynthia Bee-10 Buck Magdalena Spring (Mrs. John #1) 1805 1874 1st w/o John Buck Bee-10 Burris Ida B. (Mrs. James) 11-6-1858 2/12/1927 d/o Moses D. Burch & Efamia Beach; m. James R. Burris 1881; m/o Ora F. Bee-10 Burris James I. 5-7-1854 11/8/1921 s/o Robert & Pauline Rich Burris; m. Ida; f/o Son-Professor O.F. Burris Bee-10 Burris Ora F. 1886 2-11-1975 s/o James & Ida Burris Bee-10 Burris Zelma Ethel 7-15-1894 1-18-1959 d/o Elkanah W. & Mahala Ellen Smith Howard Bee-11 Lamkin Althea Leonard (Mrs. Benjamin F.) 7-15-1844 3/17/1931 b. Anderson, IN; d/o Samuel & Amanda Eads Brown b. Ohio Co, IN ; s/o Judson & Barbara Ellen Dyer Lamkin; m. Althea Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Franklin 1-7-1836 1/30/1914 Leonard; f/o Benjamin Franklin Lamkin Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Frank 11-9-1875 12-17-1943 Son of B.F. & Althea; Sp. Am. War Mo., Pvt. -

Medieval Ballads Instructor

Topic: Medieval Ballads Instructor: Mrs. Tincher Date: 26 Sept. 2011 Age Level: 17 to 18 yrs. Old English Level: English IV and Honors English IV Sources “The Ballad.” Grinnell College. Erik Simpson. 18 September 2011. Web. “Early Child Ballads.” PBM. Greg Lindahl. 18 September 2011. Web. Prentice Hall Literature: The British Tradition. Penguin Edition. 1 vol. New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc, 2007. Print. Rationale The NCSCoS requires that we explore British literature, and medieval ballads were an important part of the evolution of British literature. Also, studying ballads gives us, as readers, insight into the lives of those living in the medieval time period much like studying music from our own culture gives us insight into the workings of our own society. Focus & Review Journal: One hundred years from now a historian is given songs from today to analyze and learn how we lived as a society. What kinds of songs would they look at? What assumptions do you think the historian would make about our society? Do you think that the songs would give them a good idea of what life is like today? Objectives Students will understand the history and composition of ballads and how they relate to medieval history. NCSCoS Standards 1.02 Respond to texts so that the audience will: make connections between the learner's life and the text reflect on how cultural or historical perspectives may have influenced these responses 2.02 Analyze general principles at work in life and literature by: discovering and defining principles at work in personal experience and in literature. -

Representative Poetry

REPRESENTATIVE POETRY BALLADS SIR PATRICK SPENS The king sits in Dumferling toune, Drinking the blude-reid wine: "0whar will I get guid sailor, To sail this schip of mine? " Up and spak an eldern knicht, Sat at the kings richt kne: "Sir Patrick Spence is the best sailor, That sails upon the se." The king has written a braid letter, And signd it wi his hand, 10 And sent it to Sir Patrick Spence, Was walking on the sand. The first line that Sir Patrick red, A loud lauch lauched he ; The next line that Sir Patrick red, The teir blinded his ee. "0wha is this has don this deid, This ill deid don to me, To send me out this time o' the yeir, To sail upon the se! 20 "Mak hast, mak haste, my mirry men all, Our guid schip sails the morne:" "0say na sae, my.master deir, For I feir a deadlie storme. "Late, late yestreen I saw the new moone, Wi the auld moone in hir arme, And I feir, I feir, my deir master, That we will cum to harrne." 0 our Scots nobles wer richt laith To weet their cork-heild schoone; 30 Bot lang owre a' the play wer playd, Thair hats they swam aboone. 0 lang, lang may their ladies sit, Wi thair fans into their hand, Or eir they se Sir Patrick Spence Cum sailing to the land. 0 lang, lang may the ladies stand, Wi thair gold kems in their hair, Waiting for thair ain deir lords, For they'll se thame na mair. -

English 577.02 Folklore 2: the Traditional Ballad (Tu/Th 9:35AM - 10:55AM; Hopkins Hall 246)

English 577.02 Folklore 2: The Traditional Ballad (Tu/Th 9:35AM - 10:55AM; Hopkins Hall 246) Instructor: Richard F. Green ([email protected]; phone: 292-6065) Office Hours: Wednesday 11:30 - 2:30 (Denney 529) Text: English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ed. F.J. Child, 5 vols (Cambridge, Mass.: 1882- 1898); available online at http://www.bluegrassmessengers.com/the-305-child-ballads.aspx.\ August Thurs 22 Introduction: “What is a Ballad?” Sources Tues 27 Introduction: Ballad Terminology: “The Gypsy Laddie” (Child 200) Thurs 29 “From Sir Eglamour of Artois to Old Bangum” (Child 18) September Tues 3 Movie: The Songcatcher Pt 1 Thurs 5 Movie: The Songcatcher Pt 2 Tues 10 Tragic Ballads Thurs 12 Twa Sisters (Child 10) Tues 17 Lord Thomas and Fair Annet (Child 73) Thurs 19 Romantic Ballads Tues 24 Young Bateman (Child 53) October Tues 1 Fair Annie (Child 62) Thurs 3 Supernatural Ballads Tues 8 Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight (Child 4) Thurs 10 Wife of Usher’s Well (Child 79) Tues 15 Religious Ballads Thurs 17 Cherry Tree Carol (Child 54) Tues 22 Bitter Withy Thurs 24 Historical & Border Ballads Tues 29 Sir Patrick Spens (Child 58) Thurs 31 Mary Hamilton (Child 173) November Tues 5 Outlaw & Pirate Ballads Thurs 7 Geordie (Child 209) Tues 12 Henry Martin (Child 250) Thurs 14 Humorous Ballads Tues 19 Our Goodman (Child 274) Thurs 21 The Farmer’s Curst Wife (Child 278) S6, S7, S8, S9, S23, S24) Tues 24 American Ballads Thurs 26 Stagolee, Jesse James, John Hardy Tues 28 Thanksgiving (PAPERS DUE) Jones, Omie Wise, Pretty Polly, &c. -

Learning Lineage and the Problem of Authenticity in Ozark Folk Music

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1-1-2020 Learning Lineage And The Problem Of Authenticity In Ozark Folk Music Kevin Lyle Tharp Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Recommended Citation Tharp, Kevin Lyle, "Learning Lineage And The Problem Of Authenticity In Ozark Folk Music" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1829. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1829 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEARNING LINEAGE AND THE PROBLEM OF AUTHENTICITY IN OZARK FOLK MUSIC A Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music The University of Mississippi by KEVIN L. THARP May 2020 Copyright Kevin L. Tharp 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Thorough examination of the existing research and the content of ballad and folk song collections reveals a lack of information regarding the methods by which folk musicians learn the music they perform. The centuries-old practice of folk song and ballad performance is well- documented. Many Child ballads and other folk songs have been passed down through the generations. Oral tradition is the principal method of transmission in Ozark folk music. The variants this method produces are considered evidence of authenticity. Although alteration is a distinguishing characteristic of songs passed down in the oral tradition, many ballad variants have persisted in the folk record for great lengths of time without being altered beyond recognition. -

The Creighton-Senior Collaboration, 1932-51

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Athabasca University Library Institutional Repository The Creighton-Senior Collaboration, 1932-51 The arrival of Doreen Senior in Halifax in the book, and she was looking for a new collaborator summer of 1932 was a fortuitous event for Canadian who could note the melodies while she wrote down folksong collecting. Doreen, a friend and disciple of the words. In her autobiography, A Life in Folklore, Maud Karpeles, was a folk and country dance she recalled her first meeting with Doreen in the instructor, trained by the English Folk Dance Society, following terms: who anticipated a career as a music teacher making good use of Cecil Sharp's published collections of For years the Nova Scotia Summer School had Folk Songs for Schools. She was aware that Maud been bringing interesting people here, and one day I was invited to meet a new teacher, Miss had recently undertaken two successful collecting Doreen Senior of the English Folk Song and trips to Newfoundland (in 1929 and 1930), and was Dance Society. She liked people and they liked curious to see if Nova Scotia might similarly afford her to such an extent that whenever I met one of interesting variants of old English folksongs and her old summer school students in later years, ballads, or even songs that had crossed the Atlantic they would always ask about her. She was a and subsequently disappeared in their more urban and musician with the gift of perfect pitch and she industrialized land of origin. -

English Ballads and Turkish Turkus a Comparative Study

British Journal of Arts and Social Sciences ISSN: 2046-9578, Vol.11 No.I (2012) ©BritishJournal Publishing, Inc. 2012 http://www.bjournal.co.uk/BJASS.aspx English Ballads and Turkish Turkus a Comparative Study Elmas Sahin Assist. Prof. Elmas Sahin, Cag University, The Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Turkey, [email protected], Tel: +90 324 651 48 00, fax: +90 324 651 48 11 Abstract Although "ballad" whose origins based on the medieval period in the Western World; derived from Latin, and Italian word 'ballata' (ballare :/ = dance) to “turku” occurring approximately in the same centuries in the Eastern World, whose sources of the'' Turkish'' word sung by melodies in spoken tradition of Anatolia, a term given for folk poetry /songs "Turks" emerged in different nations and different cultures appear in similar directions. When both Ballads and folk songs as products of different cultures in terms of topics, motifs, structures and forms were analyzed are similar in many respects despite of exceptions. Here we will handle and evaluate the ballads and turkus, folk songs, being the products of different countries and cultures, according to the Comparative Literature and Criticism, and its theory by focusing the selected works, by means of a pluralistic approach. In this context these two literary genres having literary values, similar and different aspects in structure and content will be evaluated compared and contrasted in light of various methods as formal ,structural, reception and historical approaches. Keywords: ballad, turku, folk songs, folk poems, comparative literature 33 British Journal of Arts and Social Sciences ISSN: 2046-9578, Introduction Although both Ballad and Türkü are the products of different countries and cultures, except for some unimportant differences, they have similar aspects in terms of their subject, theme, motive, structure and form. -

A Collection of Ballads

A COLLECTION OF BALLADS INTRODUCTION When the learned first gave serious attention to popular ballads, from the time of Percy to that of Scott, they laboured under certain disabilities. The Comparative Method was scarcely understood, and was little practised. Editors were content to study the ballads of their own countryside, or, at most, of Great Britain. Teutonic and Northern parallels to our ballads were then adduced, as by Scott and Jamieson. It was later that the ballads of Europe, from the Faroes to Modern Greece, were compared with our own, with European Märchen, or children’s tales, and with the popular songs, dances, and traditions of classical and savage peoples. The results of this more recent comparison may be briefly stated. Poetry begins, as Aristotle says, in improvisation. Every man is his own poet, and, in moments of stronge motion, expresses himself in song. A typical example is the Song of Lamech in Genesis— “I have slain a man to my wounding, And a young man to my hurt.” Instances perpetually occur in the Sagas: Grettir, Egil, Skarphedin, are always singing. In Kidnapped, Mr. Stevenson introduces “The Song of the Sword of Alan,” a fine example of Celtic practice: words and air are beaten out together, in the heat of victory. In the same way, the women sang improvised dirges, like Helen; lullabies, like the lullaby of Danae in Simonides, and flower songs, as in modern Italy. Every function of life, war, agriculture, the chase, had its appropriate magical and mimetic dance and song, as in Finland, among Red Indians, and among Australian blacks. -

History, Ideology and Performance in Ian Brown's Mary and a Great

History, Ideology and Performance in Ian Brown’s Mary and A Great Reckonin’ Steve Cramer Ian Brown has, of course, written several plays on historical themes. In addition, and perhaps unusually for a playwright, he has also produced substantial critical writing on the uses of history on stage. At an early stage in his 1991 thesis, for example, Brown discusses the near impossibility of theatre as documentary history. In an analysis of the work of Peter Cheeseman at the Victoria Theatre, Stoke-on-Trent in the sixties, seventies and eighties, Brown cites the inevitable selectivity of the process of culling history directly from recorded historical sources. This is the case whether they are those of established historians or alternative histories to which those generally denied a voice on grounds such as class, race or gender contribute.1 Brown points out that whatever the source, the unavoidable process of ideological bias or auteurism must inevitably intrude upon the finished product. For all that, Brown as dramatist does not adopt an orthodox postmodernist position on history as something to be either ignored or fabulated into nostalgic pastiche for the sake of a present, ephemeral experience. Instead, he seeks to reappraise our accounts of history through a series of non-naturalistic tropes, intended to expose ideological imperatives in the semiotics of historical iconography. Brown’s Mary (1977)2 employs a succession of verfremdung techniques to create a continual distancing effect on his audience. Citing Peter Nichols’ The National Health (1970) among his influences, Brown states the intention of dislocating audience expectations through a series of parodic turns, never allowing his audience to settle with the comfortable mythologies of Mary, Queen of Scots. -

Singing the Child Ballads

Singing the Child Ballads In this column Rosaleen Gregory continues her composite, said to be collected from “various journey through the Child ballads in her own sources”. The tune is from Alexander Keith’s repertoire, and calls for readers’ submissions of selection from Gavin Greig’s collecting, Last alternative versions that they sing, or of other ballads Leaves of the Traditional Ballads and Ballad in the Child canon that she does not perform. This Airs (Aberdeen: The Buchan Club, 1925). time we cover Child Nos. 16-21. The Cruel Mother, # 20 Rosaleen writes: My version is called “Down by the Greenwood Sheath and Knife, # 16 Sidey”, and is mainly that noted by Robert and Henry Hammond from Mrs. Case, at Sydling St. Nicholas, The text I sing is Child’s version A, which was Dorset, in September 1907. The Hammonds collected reprinted from William Motherwell, ed., Minstrelsy two other versions of “The Cruel Mother” in Dorset Ancient and Modern (Glasgow: John Wylie, 1827). in 1907: one from Mrs. Russell at Upwey in The ballad was noted by Motherwell in February February, and the other from Mrs. Bowring at Cerne 1825 from an informant named Mrs. King, who lived Abbas in September. Milner and Kaplan appear to in the parish of Kilbarchan. The tune is from James have collated the text from these three (and perhaps Johnson, ed., The Scots Musical Museum, Consisting other) sources, and they took the tune from that of Six Hundred Scots Songs, 2 Vols. (Edinburgh: printed by Henry Hammond in the Journal of the James Johnson, 1787-1803).