BIODIVERSITY Native Vegetation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biodiversity

Biodiversity KEY5 FACTS as hunting), as pasture grasses or as aquarium species Introduced (in the case of some marine species). They have also • Introduced species are been introduced accidentally, such as in shipments of recognised as a leading Species imported grain or in ballast water. cause of biodiversity loss Introduced plants, or weeds, can invade and world-wide. compete with native plant species for space, light, Trends water and nutrients and because of their rapid growth rates they can quickly smother native vegetation. • Rabbit numbers: a DECLINE since Similarly to weeds, many introduced animals compete introduction of Rabbit Haemorrhagic with and predate on native animals and impact on Disease (RHD, also known as calicivirus) native vegetation. They have high reproductive rates although the extent of the decline varies and can tolerate a wide range of habitats. As a result across the State. they often establish populations very quickly. •Fox numbers: DOWN in high priority Weeds can provide shelter for pest animals, conservation areas due to large-scale although they can provide food for or become habitat baiting programs; STILL A PROBLEM in for native animals. Blackberry, for example, is an ideal other parts of the State. habitat for the threatened Southern Brown Bandicoot. This illustrates the complexity of issues associated •Feral camel and deer numbers: UP. with pest control and highlights the need for control •Feral goat numbers: DECLINING across measures to have considered specific conservation Weed affected land – Mount Lofty Ranges the State. outcomes to be undertaken over time and to be Photo: Kym Nicolson •Feral pig numbers: UNKNOWN. -

Dusky Hopping Mouse

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory DUSKY HOPPING-MOUSE Notomys fuscus Conservation status Australia: Vulnerable Northern Territory: Endangered Photo: P. Canty Description as Ooldea in South Australia and east to the Victoria/New South Wales borders. The dusky hopping-mouse is characterized by its strong incisor teeth, long tail, large ears, The species has not been recorded in the dark eyes, and extremely lengthened and Northern Territory since 1939 when it was narrow hind feet, which have only four pads collected in sand dunes on Maryvale Station on the sole. The head-body length is 91-177 and on Andado Station. An earlier record is mm, tail length is 125-225 mm, and body from Charlotte Waters. weight is about 20-50 g. Coloration of the Conservation reserves where reported: upper parts varies from pale sandy brown to None. yellowish brown to ashy brown or greyish. The underparts of dusky hopping-mice are white. The fur is fine, close and soft. Long hairs near the tip of the tail give the effect of a brush. The dusky hopping-mouse has a well- developed glandular area on the underside of its neck or chest. Females have four nipples. Distribution The current distribution of the dusky hopping-mouse appears to be restricted to the eastern Lake Eyre Basin within the Known locations of the dusky hopping-mouse Simpson-Strzelecki Dunefields bioregion in (ο = pre 1970). South Australia and Queensland. An intensive survey in the 1990s located populations at Ecology eight locations in the Strzelecki Desert and adjacent Cobbler Sandhills (South Australia) The dusky hopping-mouse occupies a variety and in south-west Queensland (Moseby et al. -

Broken Hill Complex

Broken Hill Complex Bioregion resources Photo Mulyangarie, DEH Broken Hill Complex The Broken Hill Complex bioregion is located in western New South Wales and eastern South Australia, spanning the NSW-SA border. It includes all of the Barrier Ranges and covers a huge area of nearly 5.7 million hectares with approximately 33% falling in South Australia! It has an arid climate with dry hot summers and mild winters. The average rainfall is 222mm per year, with slightly more rainfall occurring in summer. The bioregion is rich with Aboriginal cultural history, with numerous archaeological sites of significance. Biodiversity and habitat The bioregion consists of low ranges, and gently rounded hills and depressions. The main vegetation types are chenopod and samphire shrublands; casuarina forests and woodlands and acacia shrublands. Threatened animal species include the Yellow-footed Rock- wallaby and Australian Bustard. Grazing, mining and wood collection for over 100 years has led to a decline in understory plant species and cover, affecting ground nesting birds and ground feeding insectivores. 2 | Broken Hill Complex Photo by Francisco Facelli Broken Hill Complex Threats Threats to the Broken Hill Complex bioregion and its dependent species include: For Further information • erosion and degradation caused by overgrazing by sheep, To get involved or for more information please cattle, goats, rabbits and macropods phone your nearest Natural Resources Centre or • competition and predation by feral animals such as rabbits, visit www.naturalresources.sa.gov.au -

Phylogenetic Structure of Vertebrate Communities Across the Australian

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2013) 40, 1059–1070 ORIGINAL Phylogenetic structure of vertebrate ARTICLE communities across the Australian arid zone Hayley C. Lanier*, Danielle L. Edwards and L. Lacey Knowles Department of Ecology and Evolutionary ABSTRACT Biology, Museum of Zoology, University of Aim To understand the relative importance of ecological and historical factors Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1079, USA in structuring terrestrial vertebrate assemblages across the Australian arid zone, and to contrast patterns of community phylogenetic structure at a continental scale. Location Australia. Methods We present evidence from six lineages of terrestrial vertebrates (five lizard clades and one clade of marsupial mice) that have diversified in arid and semi-arid Australia across 37 biogeographical regions. Measures of within-line- age community phylogenetic structure and species turnover were computed to examine how patterns differ across the continent and between taxonomic groups. These results were examined in relation to climatic and historical fac- tors, which are thought to play a role in community phylogenetic structure. Analyses using a novel sliding-window approach confirm the generality of pro- cesses structuring the assemblages of the Australian arid zone at different spa- tial scales. Results Phylogenetic structure differed greatly across taxonomic groups. Although these lineages have radiated within the same biome – the Australian arid zone – they exhibit markedly different community structure at the regio- nal and local levels. Neither current climatic factors nor historical habitat sta- bility resulted in a uniform response across communities. Rather, historical and biogeographical aspects of community composition (i.e. local lineage per- sistence and diversification histories) appeared to be more important in explaining the variation in phylogenetic structure. -

Prescribed Water Resources Areas Prescribed Surface Water Areas BORDERTOWN Baroota Morambro Creek

PORT AUGUSTA # # STREAKY BAY South Australian Arid Lands South Australian Arid Lands # WHYALLA KIMBA # # PORT PIRIE NEW SOUTH WALES Eyre Peninsula # ELLISTON CLEVE # # WALLAROO Northern and Yorke # PORT WAKEFIELD # WAIKERIE RENMARK # SPENCER GULF NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND BLANCHETOWN # Chapmans Creek Intake ! GAWLER Far North # Middle Beach Intake ! South Australian Murray-Darling Basin Prescribed Wells Area PORT LINCOLN # ! Gawler River WESTERN Northern Intake AUSTRALIA Little Para # # WAROOKA ADELAIDE Dry Creek PWA Adelaide and Mt Lofty Ranges NEW River Torrens - Karrawirra Parri MURRAY BRIDGE SOUTH # WALES Onkaparinga River L a k e A l e x a n d r i n a CAPE JERVIS # # KINGSCOTE L a k e A l b e r t VICTORIA Kangaroo Island See large map for details VICTORIA SOUTHERN OCEAN Prescribed Water Resources Areas Prescribed Surface Water Areas BORDERTOWN Baroota Morambro Creek # Barossa Valley Clare Valley Notice of Intent to Prescribe Morambro Creek and Nyroca Channel Eastern Mount Lofty Ranges Upper Wakefield Prescribed Watercourses including Cockatoo Lake Marne River and Saunders Creek SOUTH AUSTRALIA Western Mount Lofty Ranges Prescribed Watercourses PRESCRIBED WATER RESOURCES River Murray Prescribed Wells Areas ! Chapmans Creek Intake Status at 1st July 2012 South East Angas-Bremer Gawler River NARACOORTE # Central Adelaide Little Para Dry Creek ! Middle Beach Intake ´ Far North Morambro Creek and Nyroca Channel # Prescribed Watercourses including 0 20 40 60 80 100 km ROBE Lower Limestone Coast Cockatoo Lake ! Northern Intake Mallee -

Small Mammal Population Dynamics and Range Shifts with Climate

RESOURCES, DATA RESOLUTION AND SMALL MAMMAL RANGE DYNAMICS Nerissa Haby B. Env. Sci. (Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2012 Ecology and Evolutionary Biology University of Adelaide, Australia Table of contents Table of contents i Abstract ii Acknowledgements iii Declaration iv How well do existing evaluations of climate change impacts on range Introduction 1 dynamics represent Australian small mammals? Improving performance and transferability of small-mammal species Chapter 1. 8 distribution models Chapter 2. Specialist resources are key to improving small mammal distribution models 22 Scale dependency of metapopulation models used to predict climate change Chapter 3. 35 impacts on small mammals Lessons from the arid zone: using climate variables to predict small mammal Chapter 4. 52 occurrence in hot, dry environments Ecosystem dynamics, evolution and dependency of higher trophic organisms Chapter 5. 69 on resource gradients Conclusion 79 References 89 Appendix 106 Publications associated with this thesis 153 i Abstract Extensive range shift and mass extinctions resulting from climate change are predicted to impact all biodiversity on the basis of species distribution models of wide-spread and data-rich taxa (i.e. vascular plants, terrestrial invertebrates, birds). Cases that both support and contradict these predictions have been observed in empirical and modelling investigations that continue to under-represent small mammal species (Introduction). Given small mammals are primary or higher order consumers and often dispersal limited, incorporating resource gradients that define the fundamental niche may be vital for generating accurate estimates of range shift. This idea was investigated through the influence of coarse to fine resolution, landscape- and quadrat-scale data on the range dynamics of four temperate- and five arid-zone small mammals. -

Mount Lofty Ranges, South Australia V

MOUNT LOFTY RANGES, SOUTH AUSTRALIA V. Tokarev and V. Gostin Department Geology and Geophysics, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005 [email protected] INTRODUCTION would correlate with sedimentation within and around the Mount The Mount Lofty Ranges is an arcuate north–south oriented Lofty Ranges. Our method included Digital Elevation Model upland region in South Australia flanked by the St. Vincent and (DEM) data processing and visualisation, geomorphological western Murray Basins. This paper focuses on the southern analysis, field survey, and neotectonic structural interpretation. part of the Ranges between the Fleurieu Peninsula in the south This enabled us to define the main features of regolith–landscape and the Torrens River in the north (Figure 1). Traditionally, the response to the Middle Eocene–Middle Miocene neotectonic Mount Lofty Ranges was considered to be an intraplate region deformation and sea-level change. uplifted since the early Tertiary with inherited tectonic fabrics from the Delamerian structure (~500 Ma). Previous models refer to Eocene uplift resulting from compressional reactivation along PRE-MIDDLE EOCENE PALAEOPLAIN Paleozoic faults (e.g., Benbow et al., 1995; Love et al., 1995). The Gondwanan glaciation was widespread throughout the A new model of neotectonic movements, independent of ancient Australian continent. This glaciation played a significant role tectonic fabrics controlling landscape and regolith development in post-Delamerian landscape planation by eroding local uplifts has been proposed by Tokarev et al. (1999). and infilling many small depressions. Preservation of Permian landforms and sediments within this region highlights post- In this study we incorporate both neotectonic movements Permian tectonic quiescence, landscape planation and deep and sea-level change as factors governing landscape and weathering and thus provides important evidence of post-Middle regolith evolution within the southern part of the Mount Lofty Ranges. -

40 Great Short Walks

SHORT WALKS 40 GREAT Notes SOUTH AUSTRALIAN SHORT WALKS www.southaustraliantrails.com 51 www.southaustraliantrails.com www.southaustraliantrails.com NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Simpson Desert Goyders Lagoon Macumba Strzelecki Desert Creek Sturt River Stony Desert arburton W Tirari Desert Creek Lake Eyre Cooper Strzelecki Desert Lake Blanche WESTERN AUSTRALIA WESTERN Outback Great Victoria Desert Lake Lake Flinders Frome ALES Torrens Ranges Nullarbor Plain NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Simpson Desert Goyders Lagoon Lake Macumba Strzelecki Desert Creek Gairdner Sturt 40 GREAT SOUTH AUSTRALIAN River Stony SHORT WALKS Head Desert NEW SOUTH W arburton of Bight W Trails Diary date completed Trails Diary date completed Tirari Desert Creek Lake Gawler Eyre Cooper Strzelecki ADELAIDE Desert FLINDERS RANGES AND OUTBACK 22 Wirrabara Forest Old Nursery Walk 1 First Falls Valley Walk Ranges QUEENSLAND A 2 First Falls Plateau Hike Lake 23 Alligator Gorge Hike Blanche 3 Botanic Garden Ramble 24 Yuluna Hike Great Victoria Desert 4 Hallett Cove Glacier Hike 25 Mount Ohlssen Bagge Hike Great Eyre Outback 5 Torrens Linear Park Walk 26 Mount Remarkable Hike 27 The Dutchmans Stern Hike WESTERN AUSTRALI WESTERN Australian Peninsula ADELAIDE HILLS 28 Blinman Pools 6 Waterfall Gully to Mt Lofty Hike Lake Bight Lake Frome ALES 7 Waterfall Hike Torrens KANGAROO ISLAND 0 50 100 Nullarbor Plain 29 8 Mount Lofty Botanic Garden 29 Snake Lagoon Hike Lake 25 30 Weirs Cove Gairdner 26 Head km BAROSSA NEW SOUTH W of Bight 9 Devils Nose Hike LIMESTONE COAST 28 Flinders -

Access Network Changes February 2018

Access network changes February 2018 Access network changes – Additional routes for February 2018 This fact sheet contains a summary of additional routes added to heavy vehicle networks for February 2018 that did not require a gazettal notice. These changes once approved by the NHVR, were automatically updated on the NHVR Journey Planner and relevant road transport authority map. A monthly summary of the updates to heavy vehicle networks that occur directly on state road transport authority mapping sites (without any gazettal notice) can be found at www.nhvr.gov.au/access-network-changes Ref # State Road Manager Change Description 122734 NSW Inverell Shire Add Route for 25/26m B-double Oliver Street, Inverell (from Wood Street Council to Mansfield Street) 122735 NSW Griffith City Add Route for Type 1 Road Train Tyson Lane, Tharbogang (from Brogden Council (up to 36.5m) Road to Walla Avenue) 122733 NSW Tamworth Add Route for 4.6m high vehicles Jack Smyth Dr, Hillvue (from The Ringers Regional Council Road roundabout to the new entrance of AELEC located 80m west of roundabout on Jack Smyth Drive) 122737 NSW Narromine Shire Add Route for Up to Type 1 Road Dappo Road, Narromine (from A’Beckett Council Train (up to 36.5m) Street to the shaded area on Dappo Road east of Jones Circuit) N/A NSW Hay Shire Council Extend GML B-double and Road Thelangerin Road from its current end train access point to 269 Thelangerin Rd (-34.475150, 144.818916) 122834 SA Mid Murray Add Route for the following Murraylands Road, Blanchetown (from Council combinations: -

Written Submission

Rural City of Murray Bridge 1 Background: The Rural City of Murray Bridge is responsible for an area covering 1,832km2 (including a portion of the River Murray and Lake Alexandrina) and includes 975km of trafficable roads (not including those roads maintained by the South Australian Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure). The total population of the council area is estimated to be approximately 21,486 people. Our rural city is the centre of a major agricultural, transport, industrial and tourism district and is the gateway to the Murraylands Region, containing many attractions for people of all ages. Despite being only 75km from Adelaide, Murray Bridge experiences challenges associated with attracting investment and population to a regional location. Statistical Overview The Rural City of Murray Bridge has commissioned statistical analysis, which indicates that this region differs significantly from the average in a number of measures when compared with Greater Adelaide, South Australia and Australia as a whole when measured on 2016 data. The overview reveals, when compared to the national population: that the median age of Murray Bridge is older, at 41, compared to 40 for South Australia and 39 for Greater Adelaide; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population is higher at 4.6 % compared to 2.0% for South Australia and 1.4% for Greater Adelaide; Couples with children is 23%, lower than the State figure of 27% and 29% for Greater Adelaide; Median weekly household income is $974, significantly lower than the income -

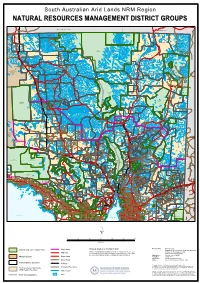

Natural Resources Management District Groups

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region NNAATTUURRAALL RREESSOOUURRCCEESS MMAANNAAGGEEMMEENNTT DDIISSTTRRIICCTT GGRROOUUPPSS NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Mount Dare H.S. CROWN POINT Pandie Pandie HS AYERS SIMPSON DESERT RANGE SOUTH Tieyon H.S. CONSERVATION PARK ALTON DOWNS TIEYON WITJIRA NATIONAL PARK PANDIE PANDIE CORDILLO DOWNS HAMILTON DEROSE HILL Hamilton H.S. SIMPSON DESERT KENMORE REGIONAL RESERVE Cordillo Downs HS PARK Lambina H.S. Mount Sarah H.S. MOUNT Granite Downs H.S. SARAH Indulkana LAMBINA Todmorden H.S. MACUMBA CLIFTON HILLS GRANITE DOWNS TODMORDEN COONGIE LAKES Marla NATIONAL PARK Mintabie EVERARD PARK Welbourn Hill H.S. WELBOURN HILL Marla - Oodnadatta INNAMINCKA ANANGU COWARIE REGIONAL PITJANTJATJARAKU Oodnadatta RESERVE ABORIGINAL LAND ALLANDALE Marree - Innamincka Wintinna HS WINTINNA KALAMURINA Innamincka ARCKARINGA Algebuckinna Arckaringa HS MUNGERANIE EVELYN Mungeranie HS DOWNS GIDGEALPA THE PEAKE Moomba Evelyn Downs HS Mount Barry HS MOUNT BARRY Mulka HS NILPINNA MULKA LAKE EYRE NATIONAL MOUNT WILLOUGHBY Nilpinna HS PARK MERTY MERTY Etadunna HS STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION ETADUNNA TALLARINGA PARK RESERVE CONSERVATION Mount Clarence HS PARK COOBER PEDY COMMONAGE William Creek BOLLARDS LAGOON Coober Pedy ANNA CREEK Dulkaninna HS MABEL CREEK DULKANINNA MOUNT CLARENCE Lindon HS Muloorina HS LINDON MULOORINA CLAYTON Curdimurka MURNPEOWIE INGOMAR FINNISS STUARTS CREEK SPRINGS MARREE ABORIGINAL Ingomar HS LAND CALLANNA Marree MUNDOWDNA LAKE CALLABONNA COMMONWEALTH HILL FOSSIL MCDOUAL RESERVE PEAK Mobella -

Arsbc-2008-Williams2 Paper.Pdf

BIOGEOGRAPHY AND BIODIVERSITY OF BIOLOGICAL SOIL CRUSTS ACROSS QUEENSLAND Wendy J. Williams1, Burkhard Büdel2, *Colin Driscoll3 1The University of Queensland, Gatton, Queensland, 4343, Australia; 2Department of Biology, University of Kaiserslautern, Kaiserslautern, Germany 3The University of Newcastle, NSW, 2308, Australia Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Recent field research has established that biological soil crust communities (cyanobacteria, lichens, liverworts and mosses) are widespread across the rangelands of Queensland. Our survey has covered many national parks and reserves or private properties where necessary, to take in changes in rainfall gradients, vegetation communities and soils. We document for the first time, well-established and extensive cyanobacteria-dominated soil crusts occurring throughout much of the gulf-savannah. An ecologically important biological crust system was found across a fragile dune and flood plain near Skull Hole, Bladensburg NP. Other noteworthy biological crusts with significant biodiversity and cover were found in the jump-ups Diamantina NP; Spinifex ridges, Minerva Hills NP; Grey Range (west of Thargomindah); Sturt Stony Desert (Arrabury region); Stony plains (Coorabulka, Windorah Rd) and Arcadia Valley (Old Towrie). There were considerable and diverse cyanobacteria-dominated soil crusts found south-east of Cunnamulla (Glencoban), Currawinya NP, Bindegolly NP, Boodjamulla NP (Lawn Hill Gorge and Riversleigh sections), sand dunes (various sites, far western QLD) and in the estuarine sand-flats around Karumba. Across western QLD several mesas were surveyed. There were also good representations of hypolithic (cyanobacteria - under quartz, Boulia-Djarra Rd), epilithic (cyanobacteria and lichens) and endolithic (cyanobacteria) communities on various granite or sandstone rocky outcrops. Early results clearly show these biogenic soil crusts are unique in their biodiversity, structure and function.