Employment and Fertility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi To cite this version: Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi. Arabic and Contact-Induced Change. 2020. halshs-03094950 HAL Id: halshs-03094950 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03094950 Submitted on 15 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language Contact and Multilingualism 1 science press Contact and Multilingualism Editors: Isabelle Léglise (CNRS SeDyL), Stefano Manfredi (CNRS SeDyL) In this series: 1. Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). Arabic and contact-induced change. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language science press Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). 2020. Arabic and contact-induced change (Contact and Multilingualism 1). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/235 © 2020, the authors Published under the Creative Commons Attribution -

Names in Multi-Lingual, -Cultural and -Ethic Contact

Oliviu Felecan, Romania 399 Romanian-Ukrainian Connections in the Anthroponymy of the Northwestern Part of Romania Oliviu Felecan Romania Abstract The first contacts between Romance speakers and the Slavic people took place between the 7th and the 11th centuries both to the North and to the South of the Danube. These contacts continued through the centuries till now. This paper approaches the Romanian – Ukrainian connection from the perspective of the contemporary names given in the Northwestern part of Romania. The linguistic contact is very significant in regions like Maramureş and Bukovina. We have chosen to study the Maramureş area, as its ethnic composition is a very appropriate starting point for our research. The unity or the coherence in the field of anthroponymy in any of the pilot localities may be the result of the multiculturalism that is typical for the Central European area, a phenomenon that is fairly reflected at the linguistic and onomastic level. Several languages are used simultaneously, and people sometimes mix words so that speakers of different ethnic origins can send a message and make themselves understood in a better way. At the same time, there are common first names (Adrian, Ana, Daniel, Florin, Gheorghe, Maria, Mihai, Ştefan) and others borrowed from English (Brian Ronald, Johny, Nicolas, Richard, Ray), Romance languages (Alessandro, Daniele, Anne, Marie, Carlos, Miguel, Joao), German (Adolf, Michaela), and other languages. *** The first contacts between the Romance natives and the Slavic people took place between the 7th and the 11th centuries both to the North and to the South of the Danube. As a result, some words from all the fields of onomasiology were borrowed, and the phonological system was changed, once the consonants h, j and z entered the language. -

2021 International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust

Glasses of those murdered at Auschwitz Birkenau Nazi German concentration and death camp (1941-1945). © Paweł Sawicki, Auschwitz Memorial 2021 INTERNATIONAL DAY OF COMMEMORATION IN MEMORY OF THE VICTIMS OF THE HOLOCAUST Programme WEDNESDAY, 27 JANUARY 2021 11:00 A.M.–1:00 P.M. EST 17:00–19:00 CET COMMEMORATION CEREMONY Ms. Melissa FLEMING Under-Secretary-General for Global Communications MASTER OF CEREMONIES Mr. António GUTERRES United Nations Secretary-General H.E. Mr. Volkan BOZKIR President of the 75th session of the United Nations General Assembly Ms. Audrey AZOULAY Director-General of UNESCO Ms. Sarah NEMTANU and Ms. Deborah NEMTANU Violinists | “Sorrow” by Béla Bartók (1945-1981), performed from the crypt of the Mémorial de la Shoah, Paris. H.E. Ms. Angela MERKEL Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany KEYNOTE SPEAKER Hon. Irwin COTLER Special Envoy on Preserving Holocaust Remembrance and Combatting Antisemitism, Canada H.E. Mr. Gilad MENASHE ERDAN Permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations H.E. Mr. Richard M. MILLS, Jr. Acting Representative of the United States to the United Nations Recitation of Memorial Prayers Cantor JULIA CADRAIN, Central Synagogue in New York El Male Rachamim and Kaddish Dr. Irene BUTTER and Ms. Shireen NASSAR Holocaust Survivor and Granddaughter in conversation with Ms. Clarissa WARD CNN’s Chief International Correspondent 2 Respondents to the question, “Why do you feel that learning about the Holocaust is important, and why should future generations know about it?” Mr. Piotr CYWINSKI, Poland Mr. Mark MASEKO, Zambia Professor Debórah DWORK, United States Professor Salah AL JABERY, Iraq Professor Yehuda BAUER, Israel Ms. -

Bo St O N College F a C T B

BOSTON BOSTON COLLEGE 2012–2013 FACT BOOK BOSTON COLLEGE FACT BOOK 2012-2013 Current and past issues of the Boston College Fact Book are available on the Boston College web site at www.bc.edu/factbook © Trustees of Boston College 1983-2013 2 Foreword Foreword The Office of Institutional Research is pleased to present the Boston College Fact Book, 2012-2013, the 40th edition of this publication. This book is intended as a single, readily accessible, consistent source of information about the Boston College community, its resources, and its operations. It is a summary of institutional data gathered from many areas of the University, compiled to capture the 2011-2012 Fiscal and Academic Year, and the fall semester of the 2012-2013 Academic Year. Where appropriate, multiple years of data are provided for historical perspective. While not all-encompassing, the Fact Book does provide pertinent facts and figures valuable to administrators, faculty, staff, and students. Sincere appreciation is extended to all contributors who offered their time and expertise to maintain the greatest possible accuracy and standardization of the data. Special thanks go to graduate student Monique Ouimette for her extensive contribution. A concerted effort is made to make this publication an increasingly more useful reference, at the same time enhancing your understanding of the scope and progress of the University. We welcome your comments and suggestions toward these goals. This Fact Book, as well as those from previous years, is available in its entirety at www.bc.edu/factbook. -

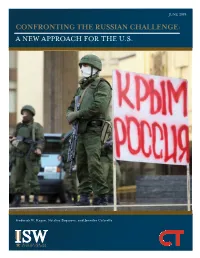

Confronting the Russian Challenge: a New Approach for the U.S

JUNE 2019 CONFRONTING THE RUSSIAN CHALLENGE: A NEW APPROACH FOR THE U.S. Frederick W. Kagan, Nataliya Bugayova, and Jennifer Cafarella Frederick W. Kagan, Nataliya Bugayova, and Jennifer Cafarella CONFRONTING THE RUSSIAN CHALLENGE: A NEW APPROACH FOR THE U.S. Cover: SIMFEROPOL, UKRAINE - MARCH 01: Heavily-armed soldiers without identifying insignia guard the Crimean parliament building next to a sign that reads: “Crimea Russia” after taking up positions there earlier in the day on March 1, 2014 in Simferopol, Ukraine. The soldiers’ arrival comes the day after soldiers in similar uniforms stationed themselves at Simferopol International Airport and Russian soldiers occupied the airport at nearby Sevastapol in moves that are raising tensions between Russia and the new Kiev government. Crimea has a majority Russian population and armed, pro-Russian groups have occupied government buildings in Simferopol. (Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images) All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing or from the publisher. ©2019 by the Institute for the Study of War and the Critical Threats Project. Published in 2019 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War and the Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 1789 Massachusetts Avenue, NW | Washington, DC 20036 understandingwar.org criticalthreats.org ABOUT THE INSTITUTE ISW is a non-partisan and non-profit public policy research organization. -

Democracy and Academic Education in Minority Languages. the Special Case of Romania Michaela Mudure

Democracy and Academic Education in Minority Languages. The Special Case of Romania Michaela Mudure Final Report During the research period for our project on Democracy and Academic Education in Minority Languages. The Special Case of Romania we worked with very varied sources in order to have a perspective as detached and comprehensive as possible. In Romania we studied the materials (books, journals, newspapers) existent at the Library of the Romanian Academy, the main library of Babe_-Bolyai University, the Library of the Faculty of Letters from Cluj, Romania. We studied the documents and statements on or of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities and the reports from the Seminar on "The Education of National Minorities in Romania". We also contacted the office of the Council of Europe in Bucharest, which proved to be very helpful. This is how we could order books/publications on democracy, human rights, minorities, human rights education and intercultural education. Studying these materials we came to the conclusion, at least, for this stage of the development of the European Union, that there is not a very precise, easy to grasp opinion of the Council of Europe on the complex issue of the relationships between the state and minorities. A lot depends on local conditions, history, activism of the minority groups, general tolerance of society. Consequently, the problem of education in minority languages, in general, and academic/tertiary education in minority languages, in particular, is also treated ambivalently in the documents of the Council of Europe. A lot is also left for the states themselves. This is understandable as the Council of Europe is based upon the voluntary acceptance of its rules by the states. -

Life Narratives, Common Language and Diverse Ways of Belonging 1

Volume 16, No. 2, Art. 16 May 2015 Life Narratives, Common Language and Diverse Ways of Belonging Katarzyna Kwapisz Williams Key words: Abstract: The article discusses my experiences of gradual immersion into the community of Polish insider; migrants to Australia, which I joined while researching life writing of Polish post-war women positionality; migrants to Australia. I focus on how my assumptions concerning commonality of culture and language; gender; language transformed during the preliminary stages of my research. I initially assumed that Polish diaspora; speaking the same language as the writers whose works I study, and their ethnic community, would Australia; life position me as a person sharing the same cultural knowledge, and allow me immediate access to writing; participant research participants. Yet, the language I considered to be the major marker of ethnic identity observation exhibited multiplicity instead of unity of experiences, positions and conceptual worlds. Instead, gender, which I had considered a fluid and unstable category highly context-dependent especially in the migration framework, proved to be an important element of interaction and communication between myself and my research participants. I have learnt that it is critical for research on diaspora, including diaspora's literary cultures, to account for other identity markers that include me as a researcher into some Polish community groups while excluding from others. I base my contribution on various kinds of materials, including field notes, fieldwork diaries and interviews with Polish writers as well as secondary literature on Poles and Australians of Polish extraction in Australia. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Locating (Myself in) the Field 3. -

Slovakia: Fertility Between Tradition and Modernity

Demographic Research a free, expedited, online journal of peer-reviewed research and commentary in the population sciences published by the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research Konrad-Zuse Str. 1, D-18057 Rostock · GERMANY www.demographic-research.org DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH VOLUME 19, ARTICLE 25, PAGES 973-1018 PUBLISHED 01 JULY 2008 http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol19/25/ DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.25 Research Article Slovakia: Fertility between tradition and modernity Michaela Potančoková Boris Vaňo Viera Pilinská Danuša Jurčová This publication is part of Special Collection 7: Childbearing Trends and Policies in Europe (http://www.demographic-research.org/special/7/) © 2008 Potančoková et al. This open-access work is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial License 2.0 Germany, which permits use, reproduction & distribution in any medium for non-commercial purposes, provided the original author(s) and source are given credit. See http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/de/ Table of Contents 1 Introduction 974 2 Fertility trends 975 2.1 Fertility tempo and quantum: from early and high towards later 975 and lower fertility 2.2 Transition to motherhood and timing of births 979 2.3 Completed family size and childlessness 984 2.4 Fertility outcomes of women by educational attainment and 986 marital status 2.5 Roma population: contrasting reproductive behavior 990 3 Proximate determinants of fertility 992 3.1 Changes in family formation 992 3.2 Sexual behavior and contraceptive -

FOCUS HUMAN RIGHTS Attack on the Istanbul Convention Michaela Lissowsky

FOCUS HUMAN RIGHTS Attack on the Istanbul Convention Michaela Lissowsky ANALYSIS Imprint Publisher Friedrich-Naumann-Stiftung für die Freiheit Truman Haus Karl-Marx-Straße 2 14482 Potsdam-Babelsberg Germany /freiheit.org /FriedrichNaumannStiftungFreiheit /FNFreiheit Authors Michaela Lissowsky Senior Advisor Human Rights & Rule of Law Editor Global Themes Unit Contact Phone: +49 30 22 01 26 34 Fax: +49 30 69 08 81 02 email: [email protected] Date December 2020 Notes on using this publication This publication is an information offer of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom. It is available free of charge and not intended for sale. It may not be used by parties or election workers for the purpose of election advertising during election campaigns (federal, state or local government elections, or European Parliament elections). FOCUS HUMAN RIGHTS 3 Table of contents Abstract _______________________________________________________________________________ 4 Pro-Family Policy vs. human rights of individuals ______________________________________ 4 Impact of the Istanbul Convention _____________________________________________________ 4 Domestic Violence Against Women in Germany ________________________________________ 6 Europe: Threatening to withdraw and resisting the Istanbul Convention ________________ 6 Hungary ______________________________________________________________________________ 6 Poland _______________________________________________________________________________ 6 Turkey ________________________________________________________________________________ -

289 Two Eight & Nine

289 TWO EIGHT & NINE SPRING 2014 | VOL. 34, NO.1 1 Lamp Post Residence Hall 15 Rodeheaver Auditorium 2 CE National 16 Gordon Recreation Center 3 East Hall / Engineering 17 Tree of Life Bookstore & Cafe 4 Alpha Residence Hall 18 Gamma C & Townhouse Residence Hall Alpha Dining Commons 18 Physical Plant Department 5 Manahan Orthopaedic Capital Center 20 Kent Residence Hall 6 Morgan Library 21 Beta Intramural Field 7 Philathea Hall 22 Cooley Science Center 8 McClain Hall 23 Creation Center 9 Epsilon Residence Hall 24 The Lodge Residence Hall 10 Indiana Residence Hall 25 Beta Residence Hall Student Affairs 26 Miller Athletic Fields Campus Safety 27 Maintenance Building Registrar / Business Office Student Health and Counseling Center 11 Lancer Lofts Residence Hall 12 Mount Memorial Hall 13 Seminary / Graduate Counseling 14 Westminster Residence Hall The New Lancer Landscape Emerging academic and residential needs are effectively redrawing the map in Winona Lake, almost yearly. We’re especially excited about the progress of the newest residence hall, the Lancer Lofts. Join us in celebrating God’s blessing with the latest bird’s-eye view. Drop by the Alumni Relations Office in the Manahan Orthopaedic Capital Center anytime for a personal tour, or join us Oct. 3-4 for Homecoming 2014! Special thanks to Scott Holladay (BA 82) for upgrading the latest edition of our campus map. From the President | Bill Katip Most Scripture translations don’t use the We venture into relevant education with required applied learning, with creating programs that match the employment word “venture,” but there are plenty of them needs of our community and the world and with degrees in the Bible. -

Hungarian Relations, Catholicism and Christian Democracy

Originalni naučni rad Michaela Moravčíková 1 UDK: 327(437.6:439) 323.1(=511.141)(437.6) 272(437.6+439) SLOVAK – HUNGARIAN RELATIONS, CATHOLICISM AND CHRISTIAN DEMOCRACY Consequences of the Treaty of Trianon In 1995 Václav Havel stated that the paths of Czechs and Germans are intertwined. One year later Rudolf Chmel, a former (and the last) Czechoslovak Ambassador to Hungary expanded on this idea that it is also true for Slovaks and Hungarians. And this is the reason why the issue of historic Slovak-Hungarian reconciliation is urgent and, in fact, fated2. The Peace Treaty of Trianon, signed in 1920, and the Treaty of Paris, signed in 1947, which replaced the Treaty of Trianon3, are considered by the Hungarians unjust and seen very neuralgic points in the history of Hungary. When the Treaty of Versailles was signed, Hungary, a mid-size European country, became one of the small states of Central Europe. In Budapest on 4 June 1920 all newspapers were printed with a black frame, the flags were placed at half-mast, usual life stopped and protest meetings took place. Following the mourning ceremonies in the basilica and other churches, the national assembly started its session. The chairman of the House of Parliament István Rakovszky in his speech, inter alia, passed the message to the “citizens of separated parts of the country”: “After a thousand years of living together, we have to separate, but not forever. From this moment all our thoughts, every beat of our hearts, day and night, will aim to reunite us, in all our former glory, all our former grandeur. -

Slovakia by Grigorij Mesežnikov and Gabriela Pleschová1

SHARP POWER Rising Authoritarian Influence CHAPTER 5 Sharp Power: Rising Authoritarian Influence Testing Democratic Resolve in Slovakia By Grigorij Mesežnikov and Gabriela Pleschová1 This study examines the soft power activities of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China as they relate to Slovakia. The “soft power” mechanisms2 of particu- lar states should be examined in a number of contexts, including the nature of the state’s political regime; the hierarchy of foreign-policy priorities of that state and the place that soft power promotion occupies in this hierarchy; the nature of bilateral relations between the pro- moter and the target of soft power; and the internal conditions in the target country. Russia and China are non-free states with nondemocratic political regimes whose actions are characterized by the illiberal exercise of power. Both are key international players: Each holds the status of permanent member of the UN Security Council, and each is a nuclear power with specific geopolitical interests accompanied by assertive or even aggressive foreign policies that are marked by expansionist practices and rhetoric. To a certain degree, these factors have prompted Russia and China to embrace similar forms of soft power strategies. At the same time, there are important differences between Russian- and Chinese-style soft power. With regard to Slovakia in particular, these differences spring from the coun- tries’ historic relationships with Central Europe and Slovakia, and their objectives in the region. Differences between Russia’s and China’s respective roles in international trade relations should be taken into account, as should the proportion and manner of their partici- pation in the international division of labor, which affects the interactions of each with the outer world.