Scheibe Poster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Honoring the Family Meal Helping Families Be Healthier and Happier with Quick, Easy Seafood Meals

Honoring the Family Meal Helping families be healthier and happier with quick, easy seafood meals OCTOBER IS NATIONAL SEAFOOD MONTH Seafood Nutrition Partnership is here to inspire Americans to enjoy seafood at least twice a week by showing how buying and Fun ways to preparing seafood is simple and delicious! USE THIS TOOLKIT For National Seafood Month in October, we are bringing the This toolkit is designed to inspire and focus back to family. demonstrate how you can implement National Seafood Month this October. Magic happens during family mealtime when children and parents Within the theme, several messaging tracks gather around the table and engage each other in conversation. Family meals eaten at home have been proven to benefit the will be promoted to speak to different health and wellness of children and adolescents, to fight obesity consumers. Please utilize the turnkey and substance abuse, and to make families stronger—creating a resources and messaging, or work with us to positive impact on our communities and our nation as a whole. customize it for your audiences. Join us as we work collaboratively with health partners, ▶ Quick, Easy Weeknight Meals seafood companies, retailers and dietitians from across the Many fish dishes cook in 15 minutes or less country to bring families back to the table. ▶ Fun Ways to Engage Seafood Nutrition Partnership is partnering with the Food Little Seafoodies Marketing Institute Foundation to emphasize the importance of Get kids cooking in the kitchen family meals, expanding National Family Meals Month throughout the year and into a true movement — the Family Meals Movement. -

Food Habits of the Southern Channel Catfish (Ictalurus Lacustris Punctatus)

FOOD IIABITS OF TIlE SOUTHERN CHANNEL CATFIStt (ICTALURUS LACUSTRIS PUNCTATUS) IN TItE DES MOINES R,IVER, 'IOWA t I•r:EVE M. BAILEY 2 Muse•,l, of Zoology, U•ffversity of Michigan,, Ann Arbor M•chigan AND H•u•¾ M. H•umso•, J•. Iowa State Co•servcttion(•ommissio,•, Des Moit•cs, Iowa .•BSTRACT The stmnaeh contents of 912 channel catfish (769 containing food) taken iu a short section of the Des Moines River from September, 1940, to October, 1911, are analyzed. The physical and biotic elmraeteristies of the study area are described; a partial list of the fishes present together xvith comments on their importance and relative abundance is included. The ehanuet eatfish is omnivorous, as is revealed by a review of the pertinent literature and by this study. A wide wtriety of organisms is eaten (some 50 families of insects alone are represented--these are listed). Insects and fish serve as staple foods, plant seeds are taken i• season, and various other items are eaten in limited numbers. The principal groups of foods (insects, fish, plants, and miscellaneous) are anMyzed volumetrically, by œrequeney of occurrence, and numerically. In the area studied, catfish grow at a rate of about 4 inches a year during the first 3 years of life (determined by length-frequency analysis). These natural size groups are utilized to establish the relationship between size and food habits. Young fish feed ahnost exclusively on aquatic insect larvae--chiefly midges, blackflies, mayflies, and enddis flies. In fish frmn 4 to 12 inches lo•g insects continue to make up the bulk of the food, but at progressively greater size larger insects (mayflies and caddis flies) are eaten with increasing frequency and dipterans are of less importonce than in the smaller size group; snmll fish and plant seeds become significant items of diet. -

A Reconnaissance of the Deeper Jamaican Coral Reef Fish Communities M

Northeast Gulf Science Volume 12 Article 3 Number 1 Number 1 11-1991 A Reconnaissance of the Deeper Jamaican Coral Reef Fish Communities M. Itzkowitz Lehigh University M. Haley Lehigh University C. Otis Lehigh University D. Evers Lehigh University DOI: 10.18785/negs.1201.03 Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/goms Recommended Citation Itzkowitz, M., M. Haley, C. Otis and D. Evers. 1991. A Reconnaissance of the Deeper Jamaican Coral Reef Fish Communities. Northeast Gulf Science 12 (1). Retrieved from https://aquila.usm.edu/goms/vol12/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gulf of Mexico Science by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Itzkowitz et al.: A Reconnaissance of the Deeper Jamaican Coral Reef Fish Communiti Northeast Gulf Science Vol. 12, No. 1 November 1991 p. 25·34 A RECONNAISSANCE OF THE DEEPER JAMAICAN CORAL REEF FISH COMMUNITIES M. Itzkowitz, M. Haley, C. Otis, D. Evers Biology Department Lehigh University Bethlehem, PA, 18015 ABSTRACT: A submersible was used to make repetitive dives in Jamaica to depths of 2S m 50 m, and 100m. With increasing depth there was a decline in both species and the numbe; of individuals. The territorial damselfish and mixed-species groups of herbivorous fishes were conspicuously absent at 100m. Few unique species appeared with increasing depth and thus the deep community resembled depauperate versions of the shallower communities. Twelve species were shared between the 3 depths but there was no significant correlation in ranked relative abundance. -

Invasive Catfish Management Strategy August 2020

Invasive Catfish Management Strategy August 2020 A team from the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries uses electrofishing to monitor invasive blue catfish in the James River in 2011. (Photo by Matt Rath/Chesapeake Bay Program) I. Introduction This management strategy portrays the outcomes of an interactive workshop (2020 Invasive Catfish Workshop) held by the Invasive Catfish Workgroup at the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Rice Rivers Center in Charles City, Virginia on January 29-30, 2020. The workshop convened a diverse group of stakeholders to share the current scientific understanding and priority issues associated with invasive catfishes in Chesapeake Bay. The perspectives shared and insights gained from the workshop were used to develop practical, synergistic recommendations that will improve management and mitigate impacts of these species across jurisdictions within the watershed. Blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus) and flathead catfish (Pylodictis olivaris) are native to the Ohio, Missouri, Mississippi, and Rio Grande river basins, and were introduced into the Virginia tributaries of Chesapeake Bay in the 1960s and 1970s to establish a recreational fishery. These non-native species have since spread, inhabiting nearly all major tributaries of the Bay watershed. Rapid range expansion and population growth, particularly of blue catfish, have led to increasing concerns about impacts on the ecology of the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem. 1 Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy Invasive Catfish Blue and flathead catfishes are long-lived species that can negatively impact native species in Chesapeake Bay through predation and resource competition. Blue catfish are generalist feeders that prey on a wide variety of species that are locally abundant, including those of economic importance and conservation concern, such as blue crabs, alosines, Atlantic menhaden, American eels, and bay anchovy. -

Feeding Catfish in Commercial Ponds

SRAC Publication No. 181 February 2008 VI PR Revision Feeding Catfish in Commercial Ponds Menghe H. Li 1 and Edwin H. Robinson 1 Since feeding is the most impor - to meet the fishes’ total nutritional motes total consumption to avoid tant task in the intensive pond requirements for normal growth waste and higher production cost. production of catfish, the person and development. All catfish feeds Catfish feeds are available as meal responsible for feeding should be are manufactured commercially; (powder), crumbles, and floating an experienced fish culturist who none are prepared on the farm. or slow-sinking pellets. Sinking can tell whether or not the fish are Manufacturers usually produce feeds (prepared in a pellet mill) feeding normally by observing “least-cost” formulations rather are seldom used in catfish produc - them as they come to the surface than “fixed-formula” feeds. In tion. Some producers use sinking to feed. This is generally the only least-cost feed formulation, the medicated feed containing oxyte - time the fish can be seen during formulas vary as ingredient prices tracycline because the antibiotic is grow out. Feeding behavior can be change. However, there are several sensitive to the high heat used in an important clue to the general limitations in the manufacture of the manufacture of floating feeds. health of the fish and the pond catfish feed using least-cost formu - However, there are now floating environment. If the fish are not lations. oxytetracycline-medicated feeds feeding normally, the person who made with “cold-extrusion” tech - is feeding must inform the farm • There is a relatively small num - nology. -

Clean &Unclean Meats

Clean & Unclean Meats God expects all who desire to have a relationship with Him to live holy lives (Exodus 19:6; 1 Peter 1:15). The Bible says following God’s instructions regarding the meat we eat is one aspect of living a holy life (Leviticus 11:44-47). Modern research indicates that there are health benets to eating only the meat of animals approved by God and avoiding those He labels as unclean. Here is a summation of the clean (acceptable to eat) and unclean (not acceptable to eat) animals found in Leviticus 11 and Deuteronomy 14. For further explanation, see the LifeHopeandTruth.com article “Clean and Unclean Animals.” BIRDS CLEAN (Eggs of these birds are also clean) Chicken Prairie chicken Dove Ptarmigan Duck Quail Goose Sage grouse (sagehen) Grouse Sparrow (and all other Guinea fowl songbirds; but not those of Partridge the corvid family) Peafowl (peacock) Swan (the KJV translation of “swan” is a mistranslation) Pheasant Teal Pigeon Turkey BIRDS UNCLEAN Leviticus 11:13-19 (Eggs of these birds are also unclean) All birds of prey Cormorant (raptors) including: Crane Buzzard Crow (and all Condor other corvids) Eagle Cuckoo Ostrich Falcon Egret Parrot Kite Flamingo Pelican Hawk Glede Penguin Osprey Grosbeak Plover Owl Gull Raven Vulture Heron Roadrunner Lapwing Stork Other birds including: Loon Swallow Albatross Magpie Swi Bat Martin Water hen Bittern Ossifrage Woodpecker ANIMALS CLEAN Leviticus 11:3; Deuteronomy 14:4-6 (Milk from these animals is also clean) Addax Hart Antelope Hartebeest Beef (meat of domestic cattle) Hirola chews -

Sharkcam Fishes

SharkCam Fishes A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower By Erin J. Burge, Christopher E. O’Brien, and jon-newbie 1 Table of Contents Identification Images Species Profiles Additional Info Index Trevor Mendelow, designer of SharkCam, on August 31, 2014, the day of the original SharkCam installation. SharkCam Fishes. A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower. 5th edition by Erin J. Burge, Christopher E. O’Brien, and jon-newbie is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. For questions related to this guide or its usage contact Erin Burge. The suggested citation for this guide is: Burge EJ, CE O’Brien and jon-newbie. 2020. SharkCam Fishes. A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower. 5th edition. Los Angeles: Explore.org Ocean Frontiers. 201 pp. Available online http://explore.org/live-cams/player/shark-cam. Guide version 5.0. 24 February 2020. 2 Table of Contents Identification Images Species Profiles Additional Info Index TABLE OF CONTENTS SILVERY FISHES (23) ........................... 47 African Pompano ......................................... 48 FOREWORD AND INTRODUCTION .............. 6 Crevalle Jack ................................................. 49 IDENTIFICATION IMAGES ...................... 10 Permit .......................................................... 50 Sharks and Rays ........................................ 10 Almaco Jack ................................................. 51 Illustrations of SharkCam -

Caranx Ruber (Red Jack Or Bar Jack)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Caranx ruber (Red Jack or Bar Jack) Family: Carangidae (Jacks and Pompanos) Order: Perciformes (Perch and Allied Fish) Class: Actinopterygii (Ray-finned Fish) Fig. 1. Red jack, Caranx ruber. [http://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/82330-Caranx-ruber, downloaded 6 March 2016] TRAITS. The red jack Caranx ruber grows to a recorded maximum length of 69cm (commonly less than 40cm) and weight of 6.8kg (Froese and Pauly, 2013). It is a laterally-flattened fish with medium sized eyes and long pectoral fins, silver in colour, tinted grey above and white below. There is an extended dark bar (golden-brow to black, with a streak of electric blue) along the back and into the lower lobe of the caudal (tail) fin (Fig. 1) which gives the species its alternative name of bar jack (Perrotta, 2004). The juveniles have six dark vertical bars. The mouth of the red jack has outer canine teeth and an inner band of teeth in the upper jaw, but the lower jaw only contains one band of teeth. DISTRIBUTION. The red jack is found in both tropical and subtropical areas of the western Atlantic Ocean and is said to be a common species (Carpenter, 2002). In the north, its limit is New Jersey, USA, and it extends south along the continental coast to Venezuela, including UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Bermuda and the West Indies, in offshore waters (Fig. 2) (Froese and Pauly, 2013). It has also been reported far offshore at Saint Helena in the south central Atlantic (Edwards, 1993). -

Courtship and Spawning Behaviors of Display Circa Lunar Periodicity When Spawning Naturally

ART & EQUATIONS ARE LINKED PREFLIGHT GOOD 426 Courtship and spawning behaviors of display circa lunar periodicity when spawning naturally. carangid species in Belize Permit represent a valuable re- source for recreational fishermen Rachel T. Graham throughout their range. In Florida, recreational fisheries land more than Wildlife Conservation Society 100,000 fish per year, but declines in P.O. Box 37 landings from 1991 to date prompted Punta Gorda, Belize regulation (Crabtree et al., 2002) and E-mail address: [email protected] a move towards catch-and-release of fish. As such, Belize is rapidly be- Daniel W. Castellanos coming known as a world-class fly- Monkey River Village fishing location due to its abundance Toledo District, Belize of permit. The fishery is highly lucra- tive: flyfishers pay up to US$500 per day in Belize to catch and release a permit. This niche tourism industry has also become an economic alter- native for local fishermen (Heyman Many species of reef fish aggre- characteristics to the closely related and Graham3). Consequently, infor- gate seasonally in large numbers T. carolinus that displays a clear cir- mation on the timing and behavior of to spawn at predictable times and cadian rhythm entrained to the light reproduction of permit can underpin sites (Johannes, 1978; Sadovy, 1996; phase during its feeding period (Heil- conservation efforts that focus on a Domeier and Colin, 1997). Although man and Spieler, 1999). According to vulnerable stage in their life cycle. spawning behavior has been observed otolith analysis of fish caught in Flor- for many reef fish in the wild (Wick- ida, permit live to at least 23 years lund, 1969; Smith, 1972; Johannes, and reach a maximum published fork 1978; Sadovy et al., 1994; Aguilar length of 110 cm and a weight of 23 Perera and Aguilar Davila, 1996), kg (Crabtree et al., 2002).1,2 Permit few records exist of observations on are gonochoristic and Crabtree et al. -

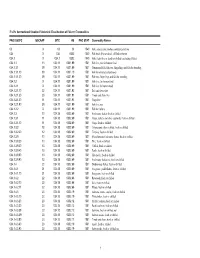

FAO's International Standard Statistical Classification of Fishery Commodities

FAO's International Standard Statistical Classification of Fishery Commodities FAO ISSCFC ISSCAAP SITC HS FAO STAT Commodity Names 03 X 03 03 1540 Fish, crustaceans, molluscs and preparations 034 X 034 0302 1540 Fish fresh (live or dead), chilled or frozen 034.1 X 034.1 0302 1540 Fish, fresh (live or dead) or chilled (excluding fillets) 034.1.1 13 034.11 0301.99 1501 Fish live, not for human food 034.1.1.1 39 034.11 0301.99 1501 Ornamental fish, fish ova, fingerlings and fish for breeding 034.1.1.1.10 39 034.11 0301.10 1501 Fish for ornamental purposes 034.1.1.1.20 39 034.11 0301.99 1501 Fish ova, fingerlings and fish for breeding 034.1.2 X 034.110301.99 1501 Fish live, for human food 034.1.2.1 X 034.110301.99 1501 Fish live for human food 034.1.2.1.10 22 034.11 0301.92 1501 Eels and elvers live 034.1.2.1.20 23 034.11 0301.91 1501 Trouts and chars live 034.1.2.1.30 11 034.11 0301.93 1501 Carps live 034.1.2.1.90 39 034.11 0301.99 1501 Fish live, nei 034.1.2.2 X 034.110301.99 1501 Fish for culture 034.1.3 10 034.18 0302.69 1501 Freshwater fishes, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.1 11 034.18 0302.69 1501 Carps, barbels and other cyprinids, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.1.10 11 034.18 0302.69 1501 Carps, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.2 12 034.18 0302.69 1501 Tilapias and other cichlids, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.2.20 12 034.18 0302.69 1501 Tilapias, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.9 10 034.18 0302.69 1501 Miscellaneous freshwater fishes, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.9.20 13 034.18 0302.69 1501 Pike, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.9.30 13 034.18 0302.69 1501 Catfish, fresh or -

Should I Eat the Fish I Catch?

EPA 823-F-14-002 For More Information October 2014 Introduction What can I do to reduce my health risks from eating fish containing chemical For more information about reducing your Fish are an important part of a healthy diet. pollutants? health risks from eating fish that contain chemi- Office of Science and Technology (4305T) They are a lean, low-calorie source of protein. cal pollutants, contact your local or state health Some sport fish caught in the nation’s lakes, Following these steps can reduce your health or environmental protection department. You rivers, oceans, and estuaries, however, may risks from eating fish containing chemical can find links to state fish advisory programs Should I Eat the contain chemicals that could pose health risks if pollutants. The rest of the brochure explains and your state’s fish advisory program contact these fish are eaten in large amounts. these recommendations in more detail. on the National Fish Advisory Program website Fish I Catch? at: http://water.epa.gov/scitech/swguidance/fish- The purpose of this brochure is not to 1. Look for warning signs or call your shellfish/fishadvisories/index.cfm. discourage you from eating fish. It is intended local or state environmental health as a guide to help you select and prepare fish department. Contact them before you You may also contact: that are low in chemical pollutants. By following fish to see if any advisories are posted in these recommendations, you and your family areas where you want to fish. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency can continue to enjoy the benefits of eating fish. -

Coral Reef Food Web ×

This website would like to remind you: Your browser (Apple Safari 4) is out of date. Update your browser for more × security, comfort and the best experience on this site. Illustration MEDIA SPOTLIGHT Coral Reef Food Web Journey Through the Trophic Levels of a Food Web For the complete illustrations with media resources, visit: http://education.nationalgeographic.com/media/coral-reef-food-web/ A food web consists of all the food chains in a single ecosystem. Each living thing in an ecosystem is part of multiple food chains. Each food chain is one possible path that energy and nutrients may take as they move through the ecosystem. Not all energy is transferred from one trophic level to another. Energy is used by organisms at each trophic level, meaning that only part of the energy available at one trophic level is passed on to the next level. All of the interconnected and overlapping food chains in an ecosystem make up a food web. Similarly, a single organism can serve more than one role in a food web. For example, a queen conch can be both a consumer and a detritivore, or decomposer. Food webs consist of different organism groupings called trophic levels. In this example of a coral reef, there are producers, consumers, and decomposers. Producers make up the first trophic level. A producer, or autotroph, is an organism that can produce its own energy and nutrients, usually through photosynthesis or chemosynthesis. Consumers are organisms that depend on producers or other consumers to get their food, energy, and nutrition. There are many different types of consumers.