Invasive Catfish Management Strategy August 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sandies, Hybrids Hot Bites

Hunting Texas Special section inside * August 8, 2008 Texas’ Premier Outdoor Newspaper Volume 4, Issue 24 * Hunting Annual 2008 www.lonestaroutdoornews.com INSIDE HUNTING Sandies, hybrids hot bites Schools keep anglers in class The Texas Animal Health Commission approved new BY CRAIG NYHUS rules permitting the transport of male hogs to Summer means hot white bass and hybrid striped authorized game ranches bass action at many Texas lakes, and North Texas without requiring blood lakes like Lake Ray Hubbard, Ray Roberts, Lewisville tests for swine disease. and Richland Chambers lead the way for many. Page 6 Gary Goldsmith, a retired principal, fished Lewisville Lake with Art Kenney and Michael The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Anderson. “We caught and released more than 100 Service approved liberal sand bass reaching the 2-pound mark,” Goldsmith waterfowl limits for the said. “With 30 minutes of daylight left we went to an 2008-2009 season. area called Queen’s Point for hybrids. As soon as we Page 7 started the bite was on — we caught 20 more fish at that spot.” FISHING The group was fishing Lead Babies Slabs in 18 feet of water. “It’s best to keep them as close to the bottom as possible when fishing for hybrids,” Goldsmith said. East Texas lakes find crappie fishermen switching gears to chase sandies when the crappie bite slows. West Texas reservoirs see the whites hitting on top. And in the Hill Country, the Highland Lakes often get hot. “All of the fish are on the main lakes,” said Joe Bray, who guides on several Hill Country lakes. -

The Koi Herpesvirus (Khv): an Alloherpesviru

Aquacu nd ltu a r e s e J Bergmann et al., Fish Aquac J 2016, 7:2 i o r u e r h n http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2150-3508.1000169 s a i l F Fisheries and Aquaculture Journal ISSN: 2150-3508 ResearchResearch Artilce Article OpenOpen Access Access Is There Any Species Specificity in Infections with Aquatic Animal Herpesviruses?–The Koi Herpesvirus (KHV): An Alloherpesvirus Model Sven M Bergmann1*, Michael Cieslak1, Dieter Fichtner1, Juliane Dabels2, Sean J Monaghan3, Qing Wang4, Weiwei Zeng4 and Jolanta Kempter5 1FLI Insel Riems, Südufer 10, 17493 Greifswald-Insel Riems, Germany 2University of Rostock, Aquaculture and Sea Ranching, Justus-von-Liebig-Weg 6, Rostock 18059, Germany 3Aquatic Vaccine Unit, Institute of Aquaculture, School of Natural Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling, FK9 4LA, UK 4Pearl-River Fisheries Research Institute, Xo. 1 Xingyu Reoad, Liwan District, Guangzhou 510380, P. R. of China 5West Pomeranian Technical University, Aquaculture, K. Królewicza 4, 71-550, Szczecin, Poland Abstract Most diseases induced by herpesviruses are host-specific; however, exceptions exist within the family Alloherpesviridae. Most members of the Alloherpesviridae are detected in at least two different species, with and without clinical signs of a disease. In the current study the Koi herpesvirus (KHV) was used as a model member of the Alloherpesviridae and rainbow trout as a model salmonid host, which were infected with KHV by immersion. KHV was detected using direct methods (qPCR and semi-nested PCR) and indirect (enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay; ELISA, serum neutralization test; SNT). The non-koi herpesvirus disease (KHVD)-susceptible salmonid fish were demonstrated to transfer KHV to naïve carp at two different temperatures including a temperature most suitable for the salmonid (15°C) and cyprinid (20°C). -

Food Habits of the Southern Channel Catfish (Ictalurus Lacustris Punctatus)

FOOD IIABITS OF TIlE SOUTHERN CHANNEL CATFIStt (ICTALURUS LACUSTRIS PUNCTATUS) IN TItE DES MOINES R,IVER, 'IOWA t I•r:EVE M. BAILEY 2 Muse•,l, of Zoology, U•ffversity of Michigan,, Ann Arbor M•chigan AND H•u•¾ M. H•umso•, J•. Iowa State Co•servcttion(•ommissio,•, Des Moit•cs, Iowa .•BSTRACT The stmnaeh contents of 912 channel catfish (769 containing food) taken iu a short section of the Des Moines River from September, 1940, to October, 1911, are analyzed. The physical and biotic elmraeteristies of the study area are described; a partial list of the fishes present together xvith comments on their importance and relative abundance is included. The ehanuet eatfish is omnivorous, as is revealed by a review of the pertinent literature and by this study. A wide wtriety of organisms is eaten (some 50 families of insects alone are represented--these are listed). Insects and fish serve as staple foods, plant seeds are taken i• season, and various other items are eaten in limited numbers. The principal groups of foods (insects, fish, plants, and miscellaneous) are anMyzed volumetrically, by œrequeney of occurrence, and numerically. In the area studied, catfish grow at a rate of about 4 inches a year during the first 3 years of life (determined by length-frequency analysis). These natural size groups are utilized to establish the relationship between size and food habits. Young fish feed ahnost exclusively on aquatic insect larvae--chiefly midges, blackflies, mayflies, and enddis flies. In fish frmn 4 to 12 inches lo•g insects continue to make up the bulk of the food, but at progressively greater size larger insects (mayflies and caddis flies) are eaten with increasing frequency and dipterans are of less importonce than in the smaller size group; snmll fish and plant seeds become significant items of diet. -

Predator/Prey Interactions, Competition, Multi

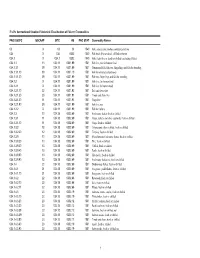

Current understanding of trophic dynamics In the Mid-Atlantic Bluefish diets, Mid Atlantic and Southern New England, NEFSC surveys 100% All others All Flatfish 90% Unid fish Unid Unid fish Unid fish Unid fish Scup 80% Scup Unid fish Scup Bluefish Butterfish Bluefish 70% Mackerel Bluefish Butterfish Butterfish Hakes 60% Loligo Drums Butterfish Unid Squid Ocean pout Round herring 50% Butterfish Ctenophores Menhaden Loligo Loligo Loligo 40% Loligo Unid Squid Round herring Illex Bay anchovy Unid Squid Unid Squid Silver anchovy Round herring Round herring 30% Bay anchovy Menhaden Unid herring Bay anchovy Menhaden Bay anchovy Striped anchovy 20% Silver anchovy Unid anchovies Bay anchovy Striped anchovy Unid anchovies 10% Striped anchovy Unid anchovies Sand lances Unid anchovies Sand lances Sand lances Sand lances 0% 1977-86 1987-96 1997-2006 2007-2013 Food web models partition mortality 100% 90% 80% If Pred > F, 70% Pred Re-evaluate 60% constant M 50% 40% Proportion of total Mortality total Proportion of F 30% 20% 10% Proportion of total mortality total of Proportion 0% Longnose skate P. Halibut W. Pollock Squids Gaichas et al. 2010 Fishing Predation Other Link et al. 2008. The Northeast U.S. continental shelf Energy Modeling and Analysis exercise (EMAX): Ecological network model development and basic ecosystem metrics. Journal of Marine Systems 74: 453-474 Intermediate tactical multispecies models An intermediate-complexity tactical ecosystem assessment tool combines: Standard stock assessment Ecosystem considerations • Structured population -

Feeding Catfish in Commercial Ponds

SRAC Publication No. 181 February 2008 VI PR Revision Feeding Catfish in Commercial Ponds Menghe H. Li 1 and Edwin H. Robinson 1 Since feeding is the most impor - to meet the fishes’ total nutritional motes total consumption to avoid tant task in the intensive pond requirements for normal growth waste and higher production cost. production of catfish, the person and development. All catfish feeds Catfish feeds are available as meal responsible for feeding should be are manufactured commercially; (powder), crumbles, and floating an experienced fish culturist who none are prepared on the farm. or slow-sinking pellets. Sinking can tell whether or not the fish are Manufacturers usually produce feeds (prepared in a pellet mill) feeding normally by observing “least-cost” formulations rather are seldom used in catfish produc - them as they come to the surface than “fixed-formula” feeds. In tion. Some producers use sinking to feed. This is generally the only least-cost feed formulation, the medicated feed containing oxyte - time the fish can be seen during formulas vary as ingredient prices tracycline because the antibiotic is grow out. Feeding behavior can be change. However, there are several sensitive to the high heat used in an important clue to the general limitations in the manufacture of the manufacture of floating feeds. health of the fish and the pond catfish feed using least-cost formu - However, there are now floating environment. If the fish are not lations. oxytetracycline-medicated feeds feeding normally, the person who made with “cold-extrusion” tech - is feeding must inform the farm • There is a relatively small num - nology. -

FAO's International Standard Statistical Classification of Fishery Commodities

FAO's International Standard Statistical Classification of Fishery Commodities FAO ISSCFC ISSCAAP SITC HS FAO STAT Commodity Names 03 X 03 03 1540 Fish, crustaceans, molluscs and preparations 034 X 034 0302 1540 Fish fresh (live or dead), chilled or frozen 034.1 X 034.1 0302 1540 Fish, fresh (live or dead) or chilled (excluding fillets) 034.1.1 13 034.11 0301.99 1501 Fish live, not for human food 034.1.1.1 39 034.11 0301.99 1501 Ornamental fish, fish ova, fingerlings and fish for breeding 034.1.1.1.10 39 034.11 0301.10 1501 Fish for ornamental purposes 034.1.1.1.20 39 034.11 0301.99 1501 Fish ova, fingerlings and fish for breeding 034.1.2 X 034.110301.99 1501 Fish live, for human food 034.1.2.1 X 034.110301.99 1501 Fish live for human food 034.1.2.1.10 22 034.11 0301.92 1501 Eels and elvers live 034.1.2.1.20 23 034.11 0301.91 1501 Trouts and chars live 034.1.2.1.30 11 034.11 0301.93 1501 Carps live 034.1.2.1.90 39 034.11 0301.99 1501 Fish live, nei 034.1.2.2 X 034.110301.99 1501 Fish for culture 034.1.3 10 034.18 0302.69 1501 Freshwater fishes, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.1 11 034.18 0302.69 1501 Carps, barbels and other cyprinids, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.1.10 11 034.18 0302.69 1501 Carps, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.2 12 034.18 0302.69 1501 Tilapias and other cichlids, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.2.20 12 034.18 0302.69 1501 Tilapias, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.9 10 034.18 0302.69 1501 Miscellaneous freshwater fishes, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.9.20 13 034.18 0302.69 1501 Pike, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.9.30 13 034.18 0302.69 1501 Catfish, fresh or -

Mid-Atlantic Forage Species ID Guide

Mid-Atlantic Forage Species Identification Guide Forage Species Identification Guide Basic Morphology Dorsal fin Lateral line Caudal fin This guide provides descriptions and These species are subject to the codes for the forage species that vessels combined 1,700-pound trip limit: Opercle and dealers are required to report under Operculum • Anchovies the Mid-Atlantic Council’s Unmanaged Forage Omnibus Amendment. Find out • Argentines/Smelt Herring more about the amendment at: • Greeneyes Pectoral fin www.mafmc.org/forage. • Halfbeaks Pelvic fin Anal fin Caudal peduncle All federally permitted vessels fishing • Lanternfishes in the Mid-Atlantic Forage Species Dorsal Right (lateral) side Management Unit and dealers are • Round Herring required to report catch and landings of • Scaled Sardine the forage species listed to the right. All species listed in this guide are subject • Atlantic Thread Herring Anterior Posterior to the 1,700-pound trip limit unless • Spanish Sardine stated otherwise. • Pearlsides/Deepsea Hatchetfish • Sand Lances Left (lateral) side Ventral • Silversides • Cusk-eels Using the Guide • Atlantic Saury • Use the images and descriptions to identify species. • Unclassified Mollusks (Unmanaged Squids, Pteropods) • Report catch and sale of these species using the VTR code (red bubble) for • Other Crustaceans/Shellfish logbooks, or the common name (dark (Copepods, Krill, Amphipods) blue bubble) for dealer reports. 2 These species are subject to the combined 1,700-pound trip limit: • Anchovies • Argentines/Smelt Herring • -

Age and Growth of the Blue Catfish, Ictalurus Furcatus, in the Arkansas River D

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 24 Article 23 1970 Age and Growth of the Blue Catfish, Ictalurus furcatus, in the Arkansas River D. Leroy Gray Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Gray, D. Leroy (1970) "Age and Growth of the Blue Catfish, Ictalurus furcatus, in the Arkansas River," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 24 , Article 23. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol24/iss1/23 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 24 [1970], Art. 23 Age and Growth of the Blue Catfish, Ictalurus furcatus, in the Arkansas River 1 D. Leroy Gray* Richard A. Collins 9 The Arkansas River has in the past been a fast-flow- After each fish had been weighed and the total ing, muddy river which fluctuated markedly in depth, but length measured, the left pectoral spine was removed as it is now in the process of being stabilized and cleared described by Sneed (1951) and Schoffman (1954). -

2021 Fish Suppliers

2021 Fish Suppliers A.B. Jones Fish Hatchery Largemouth bass, hybrid bluegill, bluegill, black crappie, triploid grass carp, Nancy Jones gambusia – mosquito fish, channel catfish, bullfrog tadpoles, shiners 1057 Hwy 26 Williamsburg, KY 40769 (606) 549-2669 ATAC, LLC Pond Management Specialist Fathead minnows, golden shiner, goldfish, largemouth bass, smallmouth bass, Rick Rogers hybrid bluegill, bluegill, redear sunfish, walleye, channel catfish, rainbow trout, PO Box 1223 black crappie, triploid grass carp, common carp, hybrid striped bass, koi, Lebanon, OH 45036 shubunkin goldfish, bullfrog tadpoles, and paddlefish (513) 932-6529 Anglers Bait-n-Tackle LLC Fathead minnows, rosey red minnows, bluegill, hybrid bluegill, goldfish and Kaleb Rodebaugh golden shiners 747 North Arnold Ave Prestonsburg, KY 606-886-1335 Andry’s Fish Farm Bluegill, hybrid bluegill, largemouth bass, koi, channel catfish, white catfish, Lyle Andry redear sunfish, black crappie, tilapia – human consumption only, triploid grass 10923 E. Conservation Club Road carp, fathead minnows and golden shiners Birdseye, IN 47513 (812) 389-2448 Arkansas Pondstockers, Inc Channel catfish, bluegill, hybrid bluegill, redear sunfish, largemouth bass, Michael Denton black crappie, fathead minnows, and triploid grass carp PO Box 357 Harrisbug, AR 75432 (870) 578-9773 Aquatic Control, Inc. Largemouth bass, bluegill, channel catfish, triploid grass carp, fathead Clinton Charlton minnows, redear sunfish, golden shiner, rainbow trout, and hybrid striped bass 505 Assembly Drive, STE 108 -

Should I Eat the Fish I Catch?

EPA 823-F-14-002 For More Information October 2014 Introduction What can I do to reduce my health risks from eating fish containing chemical For more information about reducing your Fish are an important part of a healthy diet. pollutants? health risks from eating fish that contain chemi- Office of Science and Technology (4305T) They are a lean, low-calorie source of protein. cal pollutants, contact your local or state health Some sport fish caught in the nation’s lakes, Following these steps can reduce your health or environmental protection department. You rivers, oceans, and estuaries, however, may risks from eating fish containing chemical can find links to state fish advisory programs Should I Eat the contain chemicals that could pose health risks if pollutants. The rest of the brochure explains and your state’s fish advisory program contact these fish are eaten in large amounts. these recommendations in more detail. on the National Fish Advisory Program website Fish I Catch? at: http://water.epa.gov/scitech/swguidance/fish- The purpose of this brochure is not to 1. Look for warning signs or call your shellfish/fishadvisories/index.cfm. discourage you from eating fish. It is intended local or state environmental health as a guide to help you select and prepare fish department. Contact them before you You may also contact: that are low in chemical pollutants. By following fish to see if any advisories are posted in these recommendations, you and your family areas where you want to fish. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency can continue to enjoy the benefits of eating fish. -

Fish for Your Health™ Advice for Pregnant Or Nursing Women, Women That Will Become Pregnant, and Children Under 6 Years of Age

Fish for Your Health™ Advice for pregnant or nursing women, women that will become pregnant, and children under 6 years of age 1. Eat fish – Health experts recommend that women eat 8-12 ounces/week (weight before cooking) of fish. Children, ages 2-6, should eat at least 2 ounces/week. As a reference, 3 ounces of fish is about the size of a deck of cards. Women that eat fish which contains omega-3 fatty acids (EPA & DHA) will pass these nutrients to their babies and support healthy brain and eye development. Best Choices: Eating six ounces/week of the following fish provides the recommended amounts of healthy fats and will minimize your baby’s exposure to pollutants: salmon (wild or farm-raised), rainbow trout (farm-raised), herring, mackerel (Atlantic, Jack, chub), sardine, shad (American), whitefish. 2. Before eating recreationally-caught fish, check our Fish4Health website below for your State’s fish consumption advisory and avoid eating fish that is heavily contaminated with pollutants. If a fish that you caught is not listed in the advisory, then eat no more than 1 meal per month. If you are unsure about the safety of the fish that you caught, be safe - ‘catch-and-release’. 3. Minimize your exposure to pollutants in commercial fish - follow the advice given below. (Ex: If you eat 4 ounces of albacore tuna, then don’t eat any other fish from this category until the following week.) Level of Maximum Mercury Amount for Commercial Fish Species or PCBs** Adults to Eat anchovy, butterfish, catfish (farm-raised), clam, cod, crab (Blue, King -

A Brief Diet Analysis of Common Carp and Channel Catfish by Brent Campos

A Brief Diet Analysis of Common Carp and Channel Catfish By Brent Campos Four mainstem nonnative fish, two channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) and two common carp (Cyprinus carpio), were captured using hook-and-line during our research expedition down the Grand Canyon in March, 2005. The stomachs of the fish were removed and their contents analyzed. The two species of fish appeared to exhibit divergent methods of feeding, despite having very similar organisms in their stomachs. Catfish displayed a selective, possibly mid-water picking strategy, while carp appeared to be consuming benthic substrates with their prey. Figure 1. The 405 mm common carp with its abdominal cavity cut open. Note the large ovaries, which are yellow and grainy in appearance (photo: Chris Hammersmark). One common carp was caught near sunset in a small eddy near Bass Camp at river mile 108 on March 21. It was male, measured 370 mm standard length (SL) and exhibited spawning colors. Identifiable stomach contents included aquatic Coeloptra (beetles), one oligochete, many pebbles, and detritus, among other benthic inverts. The presence of numerous pebbles indicates this fish was probing substrates for food, as would be expected for this species. The second common carp was caught near the mouth of the backwater at river mile 137, which was at the separation point of the eddy that created the site’s sandbar. The carp was female, 405 mm in length (standard length), and displayed spawning colors. Her ovaries made up approximately 50% of her abdominal cavity by volume. Gut contents were comprised of 95% algae and 5% a mix of detritus and aquatic invertebrates.