Understanding the Customer Experience for Service Design Jorge Daniel Grenha Teixeira

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two

########## Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two AU 9Gem AU 9Go! AU 9Life AU ABC AU ABC Comedy/ABC Kids NSW AU ABC Me AU ABC News AU ACCTV AU Al Jazeera AU Channel 9 AU Food Network AU Fox Sports 506 HD AU Fox Sports News AU M?ori Television NZ AU NITV AU Nine Adelaide AU Nine Brisbane AU Nine GO Sydney AU Nine Gem Adelaide AU Nine Gem Brisbane AU Nine Gem Melbourne AU Nine Gem Perth AU Nine Gem Sydney AU Nine Go Adelaide AU Nine Go Brisbane AU Nine Go Melbourne AU Nine Go Perth AU Nine Life Adelaide AU Nine Life Brisbane AU Nine Life Melbourne AU Nine Life Perth AU Nine Life Sydney AU Nine Melbourne AU Nine Perth AU Nine Sydney AU One HD AU Pac 12 AU Parliament TV AU Racing.Com AU Redbull TV AU SBS AU SBS Food AU SBS HD AU SBS Viceland AU Seven AU Sky Extreme AU Sky News Extra 1 AU Sky News Extra 2 AU Sky News Extra 3 AU Sky Racing 1 AU Sky Racing 2 AU Sonlife International AU Te Reo AU Ten AU Ten Sports AU Your Money HD AU ########## Crna Gora MNE ########## RTCG 1 MNE RTCG 2 MNE RTCG Sat MNE TV Vijesti MNE Prva TV CG MNE Nova M MNE Pink M MNE Atlas TV MNE Televizija 777 MNE RTS 1 RS RTS 1 (Backup) RS RTS 2 RS RTS 2 (Backup) RS RTS 3 RS RTS 3 (Backup) RS RTS Svet RS RTS Drama RS RTS Muzika RS RTS Trezor RS RTS Zivot RS N1 TV HD Srb RS N1 TV SD Srb RS Nova TV SD RS PRVA Max RS PRVA Plus RS Prva Kick RS Prva RS PRVA World RS FilmBox HD RS Filmbox Extra RS Filmbox Plus RS Film Klub RS Film Klub Extra RS Zadruga Live RS Happy TV RS Happy TV (Backup) RS Pikaboo RS O2.TV RS O2.TV (Backup) RS Studio B RS Nasha TV RS Mag TV RS RTV Vojvodina -

Roberta De Almeida Corrêa Cultura E

1 ROBERTA DE ALMEIDA CORRÊA CULTURA E PADRONIZAÇÃO: Produção e novas técnicas noticiosas nas seções “últimas notícias”, da Sic Online e da Globo.com (G1). FACULDADE DE LETRAS DA UNIVERSIDADE DE COIMBRA COIMBRA – PORTUGAL 2010 2 ROBERTA DE ALMEIDA CORRÊA CULTURA E PADRONIZAÇÃO: Produção e novas técnicas noticiosas nas seções “últimas notícias”, da Sic Online e da Globo.com (G1). FACULDADE DE LETRAS DA UNIVERSIDADE DE COIMBRA Dissertação de Mestrado em Comunicação e Jornalismo, especialidade em webjornalismo, apresentada à Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra, sob a orientação do Dr. Sílvio Correia Santos e da Drª. Ana Lúcia Prado. COIMBRA – PORTUGAL 2010 3 Ao meu Deus fiel que proporcionou proveitosos e inesquecíveis momentos em Portugal; aos meus pais que apostaram em meu sonho como se fosse deles sem medir esforços para realizá-lo; ao meu namorado pelo apoio durante as inesgotáveis idas às bibliotecas e também aos meus amigos brasileiros e portugueses, que ao longo de minha trajetória científica amenizaram a saudade que tive do lar. 4 AGRADECIMENTOS Ao meu orientador Sílvio Correia Santos, da Universidade de Coimbra, pelo incentivo, paciência e persistência em desenvolver um trabalho de qualidade; À co-orientadora Ana Lúcia Prado, que aceitou prosseguir comigo em mais uma etapa acadêmica. À equipe da Rede Globo, em especial da Globo Universidade, que dá suporte aos jovens cientistas de maneira esplendorosa e também à editora-chefe do portal G1, Márcia Menezes, que com muito sacrifício me encaixou num horário para visita técnica. À jornalista da Sic Online Tânia Mateus, aos diretores Ricardo Rosa, Etiano Branco e Sandra Varandas, e em especial ao diretor de informação, senhor Carlos Rodrigues por compreender a necessidade de minha visita à redação da Sic. -

CLIX SMARTV CELEBRATES TV GLOBO's 1St

Lisbon, October 2 nd , 2008 CLIX SMARTV CELEBRATES TV GLOBO’s 1st ANNIVERSARY WITH OPEN SIGNAL TRANSMISSION Lisbon, October 2 nd , 2008 - To celebrate the TV Globo Portugal’s 1st anniversary, Clix SmarTV offers this channel with open signal to its customer, on the weekend of 3rd , 4 th and 5 th October! • Clix SMARTV offers the TV Globo Portugal transmission for 3 days with open signal, to celebrate the channel’s 1st anniversary • The Premium Channel is available on Clix SMARTV, at the grid position 11, for € 9.92 per month only. With this offer, the major programs with the TV GLOBO’s seal of quality (such as the Jô Program, Mais Você, Mothern, Caldeirão do Hulk or Ivete Sangalo’s Concert) can be watched by Clix SMARTV’s customers at no additional cost, during this period. Variety and entertainment mark a programming that provides mini-series and the the most striking soap operas, exclusive interviews with the most famous stars, children's programs, documentaries, news, sports, music, television backstage scenes and a lot of humor as well as several successful programs in Brazil. The grid is a selection of TV Globo’s programming and the best channels highlights as GNT, Multishow, GloboNews and Futura. This channel is available on Clix SmarTV as a Premium Channel, on the grid position 11, for € 9.92 per month only. About Clix SmarTV This is the first digital television (IPTV) service to operate in the country. With more than 100 television channels and more than 800 titles in the Home Video service, in areas covered by Sonaecom’s last generation network, Clix SmarTV is available in 4 packages which fit each customer’s profile, and that cover from the more complete options that enable the full access to all content, to a free option offered by Clix to all Voice and Internet service customers. -

O Impacto Do Strategic Sourcing Nas Negociações De Compras Da Tv Globo

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Orientador: José Albuquerque Aluno: Rafael Pellacani Zuma / DRE: 107314922 O IMPACTO DO STRATEGIC SOURCING NAS NEGOCIAÇÕES DE COMPRAS DA TV GLOBO Rio de Janeiro, 28 de junho de 2011 Agradecimentos Agradeço a meu professor orientador, o sr. José Albuquerque, por me orientar ao longo deste trabalho, a minha família, por me dar todo o apoio e aos meus amigos, pelo apoio, orientações e por entenderem o meu ligeiro afastamento neste momento. 2 Dedicatória Dedico esta monografia a meus pais, que sempre me apoiaram e fizeram de tudo para que eu alcançasse sucesso profissional. Obrigado, vocês são e sempre serão os meus pilares. 3 Resumo O número de transações comerciais vem crescendo em todo o mundo, principalmente em países que vêm experimentando um rápido crescimento, como o Brasil. Por conseguinte, a interação entre clientes e fornecedores cresce juntamente com essa expansão. Assim, é necessário às empresas obter um relacionamento estreito com os fornecedores, a fim de obter boas condições de compra além de possíveis prioridades e/ou privilégios em situações futuras. Como exemplo, pode-se citar a crise do Japão, oriunda de desastres naturais, em que muitos fornecedores ficaram prejudicados e não puderam cumprir suas obrigações com todos os clientes. Com isso, as empresas tidas como parceiras tiveram prioridade na contratação de seus serviços e obtenção de seus produtos. É imprescindível hoje para as corporações obter vantagens competitivas em relação à concorrência. Uma vantagem muito importante é a de custo, principal razão de existência da área de compras, conseguir saving e manter a companhia com preços competitivos. -

Bárbara Smidt Weise

DIREITOS DE AUTOR E CONDIÇÕES DE UTILIZAÇÃO DO TRABALHO POR TERCEIROS Este é um trabalho académico que pode ser utilizado por terceiros desde que respeitadas as regras e boas práticas internacionalmente aceites, no que concerne aos direitos de autor e direitos conexos. Assim, o presente trabalho pode ser utilizado nos termos previstos na licença abaixo indicada. Caso o utilizador necessite de permissão para poder fazer um uso do trabalho em condições não previstas no licenciamento indicado, deverá contactar o autor, através do RepositóriUM da Universidade do Minho. Licença concedida aos utilizadores deste trabalho Atribuição CC BY https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ii AGRADECIMENTOS À minha família, minha mãe Vera, minha irmã Rachel, meus irmãos Matheus e Thomas, minha cunhadas Elisângela e Suzane, e meu mais novo amor eterno, Isis. Ao meu pai, de onde quer que ele esteja, tenho certeza que sempre acreditou em mim e na minha resiliência. As minhas amigas Alice, a professora Maria Cristina, pela ajuda, incentivo e dedicação. Sem vocês eu nem teria vindo a Portugal. E mesmo quando eu desisti inúmeras vezes, vocês não deixaram e continuavam ao meu lado. Meu agradecimento mais que especial ao meu orientador, professor Doutor Joaquim Fidalgo, que durante todos estes anos de desistência e recomeço nunca me abandonou e acreditou em mim. Sempre com sorriso no rosto a cada reunião me incentivava e fazia com que eu acreditasse na minha capacidade. Agradeço também à Universidade do Minho pela oportunidade de estudo e acolhimento. Um agradecimento especial a todos que colaboraram com esta pesquisa. Os pesquisadores e editores entrevistados. -

Media, Imigração E Minorias Étnicas 2007

MEDIA, IMIGRAÇÃO E MINORIAS ÉTNICAS 2007 ISABEL FERIN DA CUNHA CLARA ALMEIDA SANTOS WILLY FILHO ILDA FORTES 2ª EDIÇÃO - NOVEMBRO 2008 Media, Imigração e Minorias Étnicas - 2007 (1) Biblioteca Nacional - Catalogação na Publicação Media, Imigração e Minorias Étnicas - 2007 Isabel Ferin, Clara Almeida Santos - (Estudos OI; 28) ISBN 978-989-8000-46-0 I – Ferin, Isabel Santos, Clara Almeida CDU 314 316 Promotor ObservatÓRIO da Imigração www.oi.acidi.gov.pt Coordenador DO OI Roberto Carneiro Autores ISABEL FERIN CLARA ALMEIDA SANTOS WILLY FILHO ILDA FORTES Edição Alto-Comissariado para A Imigração E DIÁLOGO INTERCULTURAL (ACIDI, I.P.) RUA ÁLVARO COUTINHO, Nº14 1150-025 LISBOA Telefone: (+351) 218106100 FAX: (+351) 218106117 E-MAIL: [email protected] APOIO PAGINAÇÃO MERCADO DO DESIGN ISBN 978-989-8000-59-0 DEPÓsito Legal 227465/05 Lisboa, novembro 2008 (2) Media, Imigração e Minorias Étnicas - 2007 ÍNDICE GERAL MEDIA, IMIGRAÇÃO E MINORIAS ÉTNICAS - 2007 INTRODUÇÃO 7 CAP. 1. ANÁLISE DE IMPRENSA 10 1.1. Análise da Forma das peças 10 1.2. Análise do Conteúdo das peças 16 1.3. Análise do Discurso das peças 24 CAP. 2. ANÁLISE DA TELEVISÃO 28 2.1. Análise da Forma das peças 28 2.2. Análise do Conteúdo das peças 31 2.3 Análise do Discurso das peças 58 CONCLUSÕES 59 Conclusões Relativas à Imprensa 61 Conclusões Relativas à Televisão 62 Media, Imigração e Minorias Étnicas - 2007 (3) (4) Media, Imigração e Minorias Étnicas - 2007 MEDIA, IMIGRAÇÃO E MINORIAS ÉTNICAS - 2007 Media, Imigração e Minorias Étnicas - 2007 (5) (6) Media, Imigração e Minorias Étnicas - 2007 INTRODUÇÃO Neste relatório apresenta-se a quarta edição, referente ao ano de 2007, do Projecto Media, Imigração e Minorias Étnicas, desenvolvido com o patrocínio do Alto Comissariado para a Imigração e Diálogo Intercultural, em parceria com o Centro de Investigação Media e Jornalismo e o Instituto de Estudos Jornalísticos da Universidade de Coimbra. -

A Transformação Da Tecnologia: Mudanças Das Rotinas De Edição Da Notícia Nos Telejornais Do Brasil E De Portugal

UNIVERSIDADE DA BEIRA INTERIOR Artes e Letras A transformação da tecnologia: mudanças das rotinas de edição da notícia nos telejornais do Brasil e de Portugal Washington José de Souza Filho Tese para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Ciências da Comunicação (3º ciclo de estudos) Orientador: Prof. Doutor João Carlos Ferreira Correia Covilhã, Julho de 2015 A transformação da tecnologia ii A transformação da tecnologia Dedicatória Para Daisy – sempre - pela presença, capaz de alterar noções como o tempo e a distância. Aos meus pais - Lourdes e Washington, post mortem. Por terem mostrado o caminho, mesmo que não tenham acompanhado o percurso. Para Lara e Júlia - minhas netas. O futuro por meio do que é o presente - João Rodolpho e Matheus, meus filhos. Ao professor João Carlos Ferreira Correia, pela orientação. Uma atividade acadêmica entre as lembranças que não somos capazes de deixar no passado. iii A transformação da tecnologia iv A transformação da tecnologia Agradecimentos Uma tese é uma tarefa acadêmica, que avalia quem a faz. A prática demonstra, porém, que concluí-la não é possível sem a ajuda de muita gente. O agradecimento, ao simbolizar o reconhecimento, não basta para registrar tanta coisa, concedida por tanta gente. Atos e ações que contribuíram para realizar um objetivo. A referência a nomes, sem ocorrer, inevitavelmente, a ausência da maior parte, não diminui a contribuição recebida de muitos. Agradeço, assim, aos professores da Faculdade de Artes e Letras da Universidade da Beira Interior, do curso de Ciências da Comunicação, por meio do Presidente – e Diretor do Doutoramento -, Professor Doutor Paulo Serra, pela acolhida, o que é extensivo aos funcionários de diversos setores – em particular do Centro de Recursos de Ensino e Aprendizagem (C.R.E. -

A Televisão Em Portugal Análise Das Audiências E Dinâmicas Concorrenciais Do Mercado Televisivo Português Entre 1999 E 2016

A Televisão em Portugal Análise das audiências e dinâmicas concorrenciais do mercado televisivo português entre 1999 e 2016 RELATÓRIOS OBERCOM SETEMBRO 2017 ISSN 2182-6722 / www.obercom.pt / [email protected] Observatório da Comunicação Palácio Foz - Praça dos Restauradores 1250-187 Lisboa Portugal www.obercom.pt [email protected] Tel.: +351 213 221 319 Fax.: +351 213 221 320 FICHA TÉCNICA TÍTULO A Televisão em Portugal. Análise das audiências e dinâmicas concorrenciais do mercado televisivo português entre 1999 e 2016 DATA DA EDIÇÃO Setembro de 2017 COORDENAÇÃO CIENTÍFICA Gustavo Cardoso Sandro Mendonça AUTORIA Gustavo Cardoso Sandro Mendonça Miguel Paisana Tiago Lima Pedro Caldeira Pais Este trabalho está licenciado para Creative Commons Atribution 4.0 ISSN International (CC BY 4.0). 2182-6722 Índice Sumário Executivo ............................................................................................................................................................ 5 Análise de Indicadores ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 A expansão das marcas clássicas da televisão portuguesa .......................................................................... 8 Dinâmicas de mercado das Marcas Clássicas ............................................................................................ 13 As Marcas televisivas versus Cabo - Audiências ....................................................................................... -

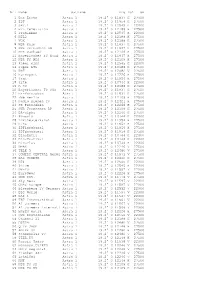

Tvbox Channel List

Nr. Name Satname Frq Pol SR 1 Das Erste Astra 1 19.2° O 11837 H 27500 2 ZDF Astra 1 19.2° O 11954 H 27500 3 SAT.1 Astra 1 19.2° O 12545 H 22000 4 RTL Television Astra 1 19.2° O 12188 H 27500 5 ProSieben Astra 1 19.2° O 12545 H 22000 6 RTL2 Astra 1 19.2° O 12188 H 27500 7 VOX Astra 1 19.2° O 12188 H 27500 8 WDR Köln Astra 1 19.2° O 11837 H 27500 9 SWR Fernsehen BW Astra 1 19.2° O 11837 H 27500 10 MDR Sachsen Astra 1 19.2° O 12109 H 27500 11 Bayerisches FS Nord Astra 1 19.2° O 11837 H 27500 12 NDR FS NDS Astra 1 19.2° O 12109 H 27500 13 kabel eins Astra 1 19.2° O 12545 H 22000 14 Super RTL Astra 1 19.2° O 12188 H 27500 15 DSF Astra 1 19.2° O 12480 V 27500 16 Eurosport Astra 1 19.2° O 12226 H 27500 17 3sat Astra 1 19.2° O 11954 H 27500 18 arte Astra 1 19.2° O 10744 H 22000 19 n-tv Astra 1 19.2° O 12188 H 27500 20 Bayerisches FS Süd Astra 1 19.2° O 11837 H 27500 21 hr-fernsehen Astra 1 19.2° O 11837 H 27500 22 rbb Berlin Astra 1 19.2° O 12109 H 27500 23 Radio Bremen TV Astra 1 19.2° O 12421 H 27500 24 SR Fernsehen Astra 1 19.2° O 12266 H 27500 25 SWR Fernsehen RP Astra 1 19.2° O 12109 H 27500 26 BR-alpha Astra 1 19.2° O 12266 H 27500 27 Phoenix Astra 1 19.2° O 10744 H 22000 28 ZDFtheaterkanal Astra 1 19.2° O 11954 H 27500 29 KiKa Astra 1 19.2° O 11954 H 27500 30 ZDFinfokanal Astra 1 19.2° O 11954 H 27500 31 ZDFdokukanal Astra 1 19.2° O 11954 H 27500 32 EinsExtra Astra 1 19.2° O 10744 H 22000 33 EinsFestival Astra 1 19.2° O 10744 H 22000 34 EinsPlus Astra 1 19.2° O 10744 H 22000 35 DMAX Astra 1 19.2° O 12246 V 27500 36 TELE 5 Astra 1 19.2° O 12480 V 27500 37 COMEDY CENTRAL Germa Astra 1 19.2° O 11973 V 27500 38 DAS VIERTE Astra 1 19.2° O 12460 H 27500 39 N24 Astra 1 19.2° O 12545 H 22000 40 9Live Astra 1 19.2° O 12545 H 22000 41 DW-TV Astra 1 19.2° O 11597 V 22000 42 EuroNews Astra 1 19.2° O 12226 H 27500 43 CNN Int. -

A Televisão Em Portugal, Medida Para Prime-Time E Share Global Entre 1999 E 2014

A Televisão em Portugal Análise das audiências e dinâmicas concorrenciais do mercado televisivo português entre 1999 e 2014 Publicações OberCom ISSN 2182-6722 1 Índice Sumário Executivo ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Análise de Indicadores ..................................................................................................................................... 7 A expansão das marcas clássicas da televisão portuguesa ................................................................................ 7 As Marcas televisivas versus cabo - Audiências .............................................................................................. 12 Os canais generalistas versus cabo - Audiências ............................................................................................ 17 Indicadores de concentração e concorrência no mercado ............................................................................... 22 As audiências por tematização de conteúdos televisivos ................................................................................. 24 Performance e audiências ........................................................................................................................... 30 Audiências de Internet vs. Audiências das marcas televisivas .......................................................................... 37 Notas Metodológicas ..................................................................................................................................... -

A Televisão Em Portugal, Medida Para Prime-Time E Share Global Entre 1999 E 2012

A Televisão em Portugal Análise das audiências e dinâmicas concorrenciais do mercado televisivo português entre 1999 e 2012 Publicações OberCom ISSN 2182-6722 0 Índice Sumário Executivo ............................................................................................................... 4 Análise de Indicadores......................................................................................................... 7 A expansão das marcas clássicas da televisão portuguesa ............................................. 7 Marcas televisivas versus cabo – Audiências ................................................................ 13 Canais generalistas versus Cabo – Audiências.............................................................. 18 Indicadores de concentração e concorrência no mercado ............................................. 24 As audiências por tematização de conteúdos televisivos ............................................... 27 Performance e audiências .............................................................................................. 33 Notas metodológicas ......................................................................................................... 43 Ficha Técnica .................................................................................................................... 46 1 Índice de Figuras e Tabelas Figura 1 – Evolução total do número de canais das marcas clássicas entre 1999 e 2012 (RTP, SIC e TVI em sinal aberto e cabo) ............................................................................................................................................................................... -

Texto Completo (395.1Kb)

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS ECONÔMICAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ECONOMIA E RELAÇÕES INTERNACIONAIS JADE LOPES PODER BRANDO E CULTURA NAS RELAÇÕES INTERNACIONAIS: O CONSUMO DE TELENOVELAS BRASILEIRAS NA ÁFRICA LUSÓFONA Porto Alegre 2016 JADE LOPES PODER BRANDO E CULTURA NAS RELAÇÕES INTERNACIONAIS: O CONSUMO DE TELENOVELAS BRASILEIRAS NA ÁFRICA LUSÓFONA Trabalho de conclusão submetido ao Curso de Graduação em Relações Internacionais da Faculdade de Ciências Econômicas da UFRGS, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título Bacharel em Relações Internacionais. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Henrique Carlos de O. Castro Porto Alegre 2016 JADE LOPES PODER BRANDO E CULTURA NAS RELAÇÕES INTERNACIONAIS: O CONSUMO DE TELENOVELAS BRASILEIRAS NA ÁFRICA LUSÓFONA Trabalho de conclusão submetido ao Curso de Graduação em Relações Internacionais da Faculdade de Ciências Econômicas da UFRGS, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título Bacharel em Relações Internacionais. Aprovada em: Porto Alegre, de de 2016. BANCA EXAMINADORA: Prof. Dr. Henrique Carlos de O. Castro – Orientador UFRGS Profª Drª Sônia Ranincheski UFRGS Prof. Dr. Leandro Valiati UFRGS AGRADECIMENTOS Ao professor Henrique, pela orientação no trabalho e principalmente por me incentivar a me colocar no texto com menos medo de errar; Ao Victor Fassina, que foi só compreensão, carinho e entusiasmo, durante a elaboração do trabalho e desde sempre; À Sandra Baptista, minha mãe, por cativar em mim a curiosidade pelo mundo e o gosto pelos estudos. Cultura é o que fica depois de se esquecer tudo o que foi aprendido. (Andre Maurois) RESUMO O presente trabalho retoma os conceitos de poder brando, de Joseph Nye, e de indústria cultural, de Theodor W.