Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Peter and St Paul Roman Catholic School, Leyburn, North Yorkshire

St Peter and St Paul Roman Catholic School, Leyburn, North Yorkshire. The Early Years 1836-1872 As well as having one of the oldest churches in the Diocese of Middlesbrough, Leybum also has one of the oldest schools. The first school of St Peter and St Paul was built along with the church and presbytery in 1835/6 and remained open until about 1872. After being closed for 23 years the existing school was enlarged and upgraded to conform with the then current requirements and opened again in 1895. It has continued to provide Catholic education for children in the area until the present day. Although log books are extant for this second period, unfortunately none have survived or were kept prior to 1895. In the early part of the 19th Century there was no organised educational provision for the children of the working class. Dame schools provided an education of sorts for younger children and older children went to Common Day Schools (run by a man), or in some areas, to Factory Schools. Sunday Schools and Charity Schools offered free education to others but on a very patchy basis. Hence in 1810 the non-conformist churches set up the British and Foreign Schools Society with the aim of building more schools and in 1811 The National Society established by the Church of England followed suit in establishing these voluntary schools. Catholic parish schools- 'day' or 'poor' schools were usually established by the joint efforts of the religious orders, the clergy and the laity. Establishment and building of the School The Leybum Catholic School appears to be unusual in that, other than a very small endowment from the Riddells, both its establishment and support seem to have been funded by the people of the area. -

Hambleton Local Plan Local Plan Publication Draft July 2019

Hambleton Local Plan Local Plan Publication Draft July 2019 Hambleton...a place to grow Foreword iv 1 Introduction and Background 5 The Role of the Local Plan 5 Part 1: Spatial Strategy and Development Policies 9 2 Issues shaping the Local Plan 10 Spatial Portrait of Hambleton 10 Key Issues 20 3 Vision and Spatial Development Strategy 32 Spatial Vision 32 Spatial Development Strategy 35 S 1: Sustainable Development Principles 35 S 2: Strategic Priorities and Requirements 37 S 3: Spatial Distribution 41 S 4: Neighbourhood Planning 47 S 5: Development in the Countryside 49 S 6: York Green Belt 54 S 7: The Historic Environment 55 The Key Diagram 58 4 Supporting Economic Growth 61 Meeting Hambleton's Employment Requirements 61 EG 1: Meeting Hambleton's Employment Requirement 62 EG 2: Protection and Enhancement of Employment Land 65 EG 3: Town Centre Retail and Leisure Provision 71 EG 4: Management of Town Centres 75 EG 5: Vibrant Market Towns 79 EG 6: Commercial Buildings, Signs and Advertisements 83 EG 7: Rural Businesses 85 EG 8: The Visitor Economy 89 5 Supporting Housing Growth 91 Meeting Hambleton's Housing Need 91 HG 1: Housing Delivery 93 HG 2: Delivering the Right Type of Homes 96 HG 3: Affordable Housing Requirements 100 HG 4: Housing Exception Schemes 103 HG 5: Windfall Housing Development 107 HG 6: Gypsies, Travellers and Travelling Showpeople 109 Hambleton Local Plan: Publication Draft - Hambleton District Council 1 6 Supporting a High Quality Environment 111 E 1: Design 111 E 2: Amenity 118 E 3: The Natural Environment 121 E -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

O R D E R .Of E X E R C I S E S at E X H I B I T I O N

ORDER .OF EXERCISES AT EXHIBITION PHILLIPS ACADEMY AndoVer, Massachusetts / JUNE 9, 1944, AT 10:30 O'CLOCK A.M. ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY-SLXTH YEAR THE ANDOVER PRESS 1944 ORDER OF EXERCISES Presiding CLAUDE MOORE FUESS Headmaster PRAYER REVEREND A. GRAHAM BALDWIN School Minister (Hum Uaune Initiation service of the Honorary Scholarship Society, Cum Laude, with an address by Kenneth C. M. Sills, LL.D., President of Bowdoin College. H&tmbtv* of thr (Elana of 1944 Elected in February HEATH LEDWARD ALLEN THOMSON COOK MCGOWAN JOHN WESSON BOLTON HENRY DEAN QUINBY, 3D CARLETON STEVENS COON, JR. JOHN BUTLER SNOOK JOHN CURTIS FARRAR DONALD JUSTUS STERLING, JR. FREDERICK DAVIS GREENE, 2D WHITNEY STEVENS ALFRED GILBERT HARRIS JOHN CINCINNATUS THOMPSON JOHN WILSON KELLETT Elected in June JOHN FARNUM BOWEN VICTOR KARL KOECHL ISAAC CHILLINGSWORTH FOSTER ERNEST CARROLL MAGISON VICTOR HENRY HEXTER, 2D ROBERT ALLEN WOFSEY DWIGHT DELAVAN KILLAM RAYMOND HENRY YOUNG CHARLES WESLEY KITTLEMAN, JR. £Am\t ANNOUNCEMENT OF HONORS AND PRIZES SPECIAL MENTION FOR DISTINGUISHED SCHOLARSHIP DURING THE SENIOR YEAR BIOLOGY Richard Schuster CHEMISTRY Carleton Stevens Coon, Jr. Ernest Carroll Magison John Curtis Farrar Donald Justus Sterling, Jr. John Wilson Kellett ENGLISH Heyward Isham Donald Justus Sterling, Jr. FBENCH Ian Seaton Pemberton GERMAN Heyward Isham Arthur Stevens Wensinger HISTORY ~John Curtis Farrar Donald Justus Sterling, Jr. Thomson Cook McGowan MATHEMATICS John Farnum Bowen >• Donald Justus Sterling, Jr. Benjamin Yates Brewster, Jr. John Cincinnatus Thompson John Curtis Farrar Robert Allen Wofsey Isaac Chillingsworth Foster Raymond Henry Young John Wilson Kellett PHYSICS John Famum Bowen Charles Wesley Kittleman, Jr. Carleton Stevens Coon, Jr. -

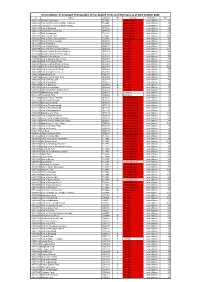

English Fords Statistics

Reconciliation of Geograph Photographs versus English Fords and Wetroads as at 03rd October 2020 Id Name Grid Ref WR County Submitter Hits 3020116 Radwell Causeway TL0056 ü Bedfordshire John Walton 37 3069286 Ford and Packhorse Bridge at Sutton TL2247 ü Bedfordshire John Walton 82 3264116 Gated former Ford at North Crawley SP9344 ü Bedfordshire John Walton 56 3020108 Ford at Farndish SP9364 ü Bedfordshire John Walton 52 3020123 Felmersham Causeway SP9957 ü Bedfordshire John Walton 37 3020133 Ford at Clapham TL0352 ü Bedfordshire John Walton 81 3020073 Upper Dean Ford TL0467 ü Bedfordshire John Walton 143 5206262 Ford at Priory Country ParK TL0748 B Bedfordshire John Walton 71 3515781 Border Ford at Headley SU5263 ü Berkshire John Walton 88 3515770 Ford at Bagnor SU5469 ü Berkshire John Walton 45 3515707 Ford at Bucklebury SU5471 ü Berkshire John Walton 75 3515679 Ford and Riders at Bucklebury SU5470 ü Berkshire John Walton 114 3515650 Byway Ford at Stanford Dingley SU5671 ü Berkshire John Walton 46 3515644 Byway Ford at Stanford Dingley SU5671 ü Berkshire John Walton 49 3492617 Byway Ford at Hurst SU7874 ü Berkshire John Walton 70 3492594 Ford ar Burghfield Common SU6567 ü Berkshire John Walton 83 3492543 Ford at Jouldings Farm SU7563 ü Berkshire John Walton 67 3492407 Byway Ford at Arborfield Cross SU7667 ü Berkshire John Walton 142 3492425 Byway Ford at Arborfield Cross SU7667 ü Berkshire John Walton 163 3492446 Ford at Carter's Hill Farm SU7668 ü Berkshire John Walton 75 3492349 Ford at Gardners Green SU8266 ü Berkshire John Walton -

Public Notice of County Treasurer's Sale of Tax

NASSAU COUNTY WEB PAGE, NCT PUBLIC NOTICE OF COUNTY TREASURER’S SALE OF TAX LIENS ON REAL ESTATE Notice is hereby given that I shall on February 17, 2015, and the succeeding days, beginning at 10:00 o' clock in the morning in the Legislative Chamber, First Floor, Theodore Roosevelt Executive and Legislative Building, 1550 Franklin Avenue, Mineola, Nassau County, New York, sell at public auction the tax liens on real estate herein-after described, unless the owner, mortgagee, occupant of or any other party-in-interest in such real estate shall pay to the County Treasurer by February 13, 2015 the total amount of such unpaid taxes or assessments with the interest, penalties and other expenses and charges, against the property. Such tax liens will be sold at the lowest rate of interest, not exceeding 10 per cent per six month's period, for which any person or persons shall offer to take the total amount of such unpaid taxes as defined in section 5-37.0 of the Nassau County Administrative Code. As required by section 5-44.0 of Nassau County Administrative Code, the County Treasurer shall charge a registration fee of $100.00 per day to each person who shall seek to bid at the public auction defined above. The liens are for arrears of School District taxes for the year 2013 - 2014 and/or County, Town, and Special District taxes for the year 2014. The following is a partial listing of the real estate located in school district number(s) 1, 301, 26, 3, 17, 13, 205, 28, 6, 122, 11, 18, 12, 21, 19, 16, 22, 20, 31, 29, 10, 8, 25, 7, 5, 15, 14, 315, 9, 24, 27, 4, 2, 23, 30, 306 in the Town of Oyster Bay, City of Long Beach, Town of North Hempstead, Town of Hempstead, City of Glen Cove only, upon which tax liens are to be sold, with a brief description of the same by reference to the County Land and Tax Map, the name of the owner or occupant as the same appears on the 2015/2016 tentative assessment roll, and the total amount of such unpaid taxes. -

The Emergence of a Catholic Identity and the Need For

THE EMERGENCE OF A CATHOLIC IDENTITY AND THE NEED FOR EDUCATIONAL AND SOCIAL PROVISION IN NINETEENTH CENTURY BRIGHTON SANDY KENNEDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION DECEMBER 2013 MY DECLARATION PLUS WORD COUNT I hereby declare that, except where explicit attribution is made, the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. Word Count: 84,109 ABSTRACT The 1829 Act of Emancipation was designed to return to Catholics the full rights of citizenship which had been denied them for over two hundred years. In practice, Protestant mistrust and Establishment fears of a revival of popery continued unabated. Yet thirty years earlier, in Regency Brighton, the Catholic community although small seemed to have enjoyed an unprecedented degree of tolerance and acceptance. This thesis questions this apparent anomaly and asks whether in the century that followed, Catholics managed to unite across class and nationality divides and establish their own identity, or if they too were subsumed into the culture of the time, subject to the strict social and hierarchical ethos of the Victorian age. It explores the inevitable tension between 'principle' and 'pragmatism' in a town so heavily dependent upon preserving an image of relaxed and welcoming populism. This is a study of the changing demography of Brighton as the Catholic population expanded and schools and churches were built to meet their needs, mirroring the situation in the country as a whole. It explains the responsibilities of Catholics to themselves and to the wider community. It offers an in-depth analysis of educational provision in terms of the structure, administration and curriculum in the schools, as provided both by the growing number of religious orders and lay teachers engaged in the care and education of both the wealthy and the poor. -

Palliative Care Clinical Academic Group Outcomes Book Outcomes

King’s Health Partners | Palliative Care Clinical Academic Group Outcomes Book Outcomes Palliative Care Clinical Academic Group i King’s Health Partners King’s Health Partners brings together: n three of the UK’s leading NHS Foundation Trusts n a world-leading university for health research and education n nearly 4.8 million patient contacts each year n 40,000 staff n nearly 30,000 students n a combined annual turnover of more than £3.7 billion n services provided across central and south London and beyond, including nine mental health and physical healthcare hospitals and many community sites n a comprehensive portfolio of high-quality clinical services with international recognition in cancer, diabetes, mental health, regenerative medicine, transplantation, cardiac and clinical neurosciences n a major trauma centre and two hyper-acute stroke units King’s Health Partners | Palliative Care Clinical Academic Group Outcomes Book About King’s Health Partners King’s Health Partners brings together n Bring together our partnership’s collective a world-leading university for health research strength in a range of specialist services to and education, King’s College London and three deliver world-class patient care and research NHS Foundation Trusts Guy’s and St Thomas’, through our institutes programme; King’s College Hospital and South London and Maudsley. n Developing education, research and capacity building programmes in global We are an Academic Health Sciences Centre health including partnerships with healthcare where world-class research, education and teams and organisations in Sierra Leone, clinical practice are brought together to Somaliland and Zambia. benefit our patients. -

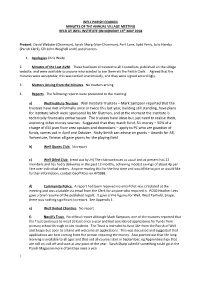

Mark Sampson Reported That the Trustees Have Met

WELL PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL VILLAGE MEETING HELD AT WELL INSTITUTE ON MONDAY 14th MAY 2018 Present: David Webster (Chairman), Sarah Sharp (Vice-Chairman), Avril Lane, Sydd Perry, Julia Hamby (Parish Clerk), Cllr John Weighell and 6 parishioners. 1. Apologies Chris Wade 2. Minutes of the Last AVM. These had been circulated to all Councillors, published on the village website, and were available to anyone who wanted to see them via the Parish Clerk. Agreed that the minutes were acceptable; this was carried unanimously, and they were signed accordingly. 3. Matters Arising from the Minutes. No matters arising 4. Reports. The following reports were presented to the meeting: a) Well Institute Trustees. Well Institute Trustees – Mark Sampson reported that the trustees have met informally once or twice this last year, building still standing, have plans for Institute which were sponsored by Mr Glatman, and at the moment the Institute is technically financially embarrassed. The trustees have ideas but just need to realise them, exploring other money sources. Suggested that they match fund, SIL money – 50% of a charge of £55 psm floor area upstairs and downstairs – apply to PC who are guardian of funds, comes out in April and October. Nicky Smith can advise on grants – Awards for All, Yorventure, Tarmac all gave grants for the playing field b) Well Quoits Club. No report c) Well Oiled Club. (read out by JH) The club continues as usual and at present has 22 members and has had 5 deliveries in the past 12 months, achieving modest savings of about 4p per litre over individual orders. -

Lets&Docs Concerning England&Ireland

Letters and Documents Concerning England and Ireland Blessed EUGENE DE MAZENOD Collection Oblate Writings III Letters and Documents Concerning England and Ireland 1842-1860 Translated by John Witherspoon Mole, O.M.I. General Postulation O.M.I. Via Aurelia 290 Rome 1979 Numerical Table 1842 1. To Fr. Casimir Aubert, July 27, 1842 1 2. To Fr.Casimir Aubert, September 26, 1842 2 3. To Fr. Casimir Aubert, December 25, 1842 3 1843 4. To Fr. Casimir Aubert in Ireland, February 19, 1843 . 5 1844 5. To Fr. Casimir Aubert at Penzance, February 1, 1844 . 7 6. To Fr. Casimir Aubert at N.D. de l’Osier, March 21, 1844 9 7. To Fr. Casimir Aubert at N.D. de l’Osier, April 17, 1844 10 8. To Fr. Casimir Aubert at N.D. de l’Osier, May 17, 1844 12 9. To Fr. Casimir Aubert at N.D. de l’Osier, June 11, 1844 13 10. To Fr. Casimir Aubert at N.D. de l’Osier, July 1, 1844 14 1845 11. To Fr. Perron at Grace-Dieu, August 25, 1845 .... 17 12. To Fr. Daly at Penzance, December 6, 1845 ............... 18 1846 13. To Fr. Casimir Aubert, July 15, 1846 ........................... 19 14. To Fr. Casimir Aubert in England, August 7, 1846 . 20 1847 15. To Archbishop John McHale of Tuam, April 14, 1847 23 16. To Miss O’Connell at Killarney, April 15, 1847 .... 24 17. To Bishop Wiseman at Rome, August 17, 1847 .... 25 1848 18. To Fr. John Naughten in England, May 1, 1848 . 27 19. -

J?, ///? Minor Professor

THE PAPAL AGGRESSION! CREATION OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC HIERARCHY IN ENGLAND, 1850 APPROVED! Major professor ^ J?, ///? Minor Professor ItfCp&ctor of the Departflfejalf of History Dean"of the Graduate School THE PAPAL AGGRESSION 8 CREATION OP THE SOMAN CATHOLIC HIERARCHY IN ENGLAND, 1850 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For she Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Denis George Paz, B. A, Denton, Texas January, 1969 PREFACE Pope Plus IX, on September 29» 1850, published the letters apostolic Universalis Sccleslae. creating a terri- torial hierarchy for English Roman Catholics. For the first time since 1559» bishops obedient to Rome ruled over dioceses styled after English place names rather than over districts named for points of the compass# and bore titles derived from their sees rather than from extinct Levantine cities« The decree meant, moreover, that6 in the Vati- k can s opinionc England had ceased to be a missionary area and was ready to take its place as a full member of the Roman Catholic communion. When news of the hierarchy reached London in the mid- dle of October, Englishmen protested against it with unexpected zeal. Irate protestants held public meetings to condemn the new prelates» newspapers cried for penal legislation* and the prime minister, hoping to strengthen his position, issued a public letter in which he charac- terized the letters apostolic as an "insolent and insidious"1 attack on the queen's prerogative to appoint bishops„ In 1851» Parliament, despite the determined op- position of a few Catholic and Peellte members, enacted the Ecclesiastical Titles Act, which imposed a ilOO fine on any bishop who used an unauthorized territorial title, ill and permitted oommon informers to sue a prelate alleged to have violated the act. -

KJ MASTER THESIS FINAL Corrections

Ordered Spaces, Separate Spheres: Women and the Building of British Convents, 1829-1939 Kate Jordan University College London Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy I, Kate Jordan confirm that the work present- ed in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. _______________________________ Kate Jordan !2 Abstract Over the last forty years, feminist discourses have made considerable impact on the way that we understand women’s historical agency. Linda Nochlin’s question, ‘why have there been no great women artists’ challenged assumptions about the way we consider women in art history and Amanda Vickery brought to the fore questions of women’s authority within ‘separate spheres’ ideology. The paucity of research on women’s historical contributions to architecture, however, is a gap that misrepresents their significant roles. This thesis explores a hitherto overlooked group of buildings designed by and for women; nineteenth and twentieth century English convents. Many of these sites were built according to the rules of communities whose ministries extended beyond contemplative prayer and into the wider community, requiring spaces that allowed lay-women to live and work within the convent walls but without disrupting the real and imagined fabric of monastic traditions - spaces that were able to synthesise contemporary domestic, industrial and institutional architecture with the medieval cloister. The demanding specifications for these highly innovative and complex spaces were drawn up, overwhelmingly, by nuns. While convents might be read as spaces which operated at the interstices between different architectures, I will argue they were instead conceived as sites that per- formed varying and contradictory functions simultaneously.