University of Nevada, Reno Looking at Femininity Through the Bottom of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continuity and Change in Indigenous Beer Entrepreneurial Activity of Women in Jos Metropolis, Nigeria

CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN INDIGENOUS BEER ENTREPRENEURIAL ACTIVITY OF WOMEN IN JOS METROPOLIS, NIGERIA: 1909-1995 NIMLAN RABI MENMAK A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY OCTOBER, 2019 ii DECLARATION This is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university. Signature………………………………. Date…………………………… Nimlan Rabi Menmak C82F/27279/2014 We confirm that the work reported in this thesis was carried out by the student under our supervision. Signature……………………………….Date………………………………… Prof. Henry Mwanzi Department of History, Archaeology and Political Studies Kenyatta University Signature……………………………….Date………………………………… Dr. Felix Kiruthu Department of History, Archaeology and Political Studies Kenyatta University iii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the Almighty God and my angel mother, Rebecca Danjuma Nimlan, my children, Shelter Ponfa Zingbon and Avery Hanan Zingbon. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My gratitude goes to Kenyatta University for giving me the opportunity to pursue my Doctorate Degree. I am greatly indebted to my supervisors, Professor Mwanzi Henry and Dr Felix Kiruthu for their guidance and advice during this study. To you my supervisors, may God bless. I also appreciate the staff of the Department of History, Archaeology and Political studies, Kenyatta University, for their support during my study especially Dr Gimode and Dr Akattu. I am grateful to the University of Jos, Nigeria through its Needs Assessment Intervention: the Disbursement of Staff Training & Development Component for funding this research work. My sincere appreciation also goes to my mentor Prof. Sati Fwatshak for his advice that led me to pursue my Ph.D. -

No. 116 Winter 2017/18

Multi-award-winning magazine of the Bristol & District and Bath & Borders branches of CAMRA, the Campaign for Real Ale No. 116 Winter 2017/18 PINTS WEST Contents Page 20 BADRAG (rare ales group) Page 24 Bath & Borders news Page 42 Beer scoring and GBG Page 42 Book reviews Page 3 Bristol Beer Festival Page 43 Bristol Beer Week Page 34 Bristol Pubs Group INTS WES Page 46 Brussels Page 48 Bucharest P T Page 51 CAMRA diaries & contacts The multi-award-winning magazine of the Bristol & District Page 22 CAMRA ladies Bristol Beer Festival 2018 branch of CAMRA, the Campaign for Real Ale, plus the Bath Page 49 CAMRA young(ish) members he twenty-first annual CAMRA Bristol Beer Festival will run from Thursday 22nd to Saturday 24th & Borders branch Page 32 Shine on pubs with theatres March 2018 at Brunel’s Old Station, Temple Meads, Bristol. There will be a carefully chosen selection Brought to you entirely by unpaid volunteers Page 40 Weston-super-Mare news Tof around 140 different real ales on sale over the course of the festival as well as a good range of cider Ten thousand copies of Pints West are distributed free to Brewery news: and perry. There will also be a variety of food available at all sessions. Beer prices will once again remain hundreds of pubs in and around the cities of Bristol and Bath Page 12 Arbor Ales unchanged with over two thirds of the beer and all of the cider priced at £3.40 per pint or below. ... and beyond Page 17 Ashley Down There is a significant change this year in the way the Also available on-line at www.bristolcamra.org.uk Page 6 Bath Ales and Beerd tickets will be sold. -

ABSTRACT ROBERTS, NATHAN ANDREW. Tapping History: Retrojection, Bridging, and Invented Tradition by North Carolina Craft Brewers

ABSTRACT ROBERTS, NATHAN ANDREW. Tapping History: Retrojection, Bridging, and Invented Tradition by North Carolina Craft Brewers (Under the Direction of Dr. Michaela DeSoucey) The growth of the American craft beer market in the past decade offers an exemplary case for examining how localization occurs as a social and contextual process. Although Watson’s (2014a) analysis for the Brewers Association stated that breaking the 3,000 mark for the number of craft brewers in the United States represented a return to the local, there is more to localization than simply where firms are located. This research examines the case of the craft beer market in the Triangle region of North Carolina to understand how localizing markets deal with limited state-level heritage and brewing traditions. Utilizing qualitative methods and drawing upon prior research, I identify strategies for localization. These include: (1) creating a group brewing identity; (2) creating heritage by revising, writing and bridging history; and (3) traditions of invention (Paxson 2013). The use of heritage and traditions represent novel uses of the past, which draw upon retrojection (Berger and Luckmann 1966) of current meanings and understandings into the past, to compel ostensible alignment with the present. Brewers tap histories to localize their products. © Copyright 2017 Nathan A. Roberts All Rights Reserved Tapping History: Retrojection, Bridging, and Invented Tradition by North Carolina Craft Brewers by Nathan Andrew Roberts A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Sociology Raleigh, North Carolina 2017 APPROVED BY: _______________________________ _______________________________ Dr. -

The Economic Impact of the Craft Beer Industry in Iowa

The Economic Impact of the Craft Beer Industry in Iowa Prepared for and funded by The Iowa Wine and Beer Promotion Board By Mike Lipsman, Harvey Siegelman, and Dan Otto Strategic Economics Group May 2015 Acknowledgements This study would not have been possible without the assistance and cooperation of a number of individuals and organizations. Colleen Murphy (Iowa Tourism Office) and J. Wilson (Iowa Brewers Guild) provided great assistance in identifying existing craft breweries and brewpubs and additional businesses still in the planning stage of development. In addition, we wish to thank them along with Ryan Rost (515 Brewing) and Bill Heinrich (Big Grove Brewery) for acting as test subjects for the Brewers Survey. We are very grateful to all of those associated with Iowa breweries and brewpubs that took time from their busy schedules to respond to the survey. Bob Bailey and Leisa Bertram (Communications Director and Accountant II, respectively, Iowa Alcoholic Beverages Division) provided invaluable help in obtaining craft beer production, distribution, and sales data, as well as information on the regulation of the industry. Also, James Morris (Iowa Workforce Development) helped by compiling and aggregating employment and wage data from Iowa breweries and brewpubs. Finally, we greatly enjoyed the visits we made to Iowa breweries and thank Dave Ropte and Ryan Rost (515 Brewing), John Martin (Confluence), and Megan McKay (Peace Tree) for the time they spent answering our many questions regarding their individual businesses and the craft beer industry. Pictures used in the report were either taken by the authors or obtained from public Internet sites. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) U.1N1 1 tlJ 2>I f\ 1 c,o Utr/\K. i IVIC.IN i wr i nc i IN i i:iviv/iv WlSii$ZKm> NATIONAL PARK SERVICE llllifllll illlllilll lilSiiiiiliiiiil iflllli ftmmmmximm•lllliiil iSSStllSIBs NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES illlllilllli ii|s£ss|iisi SSiJKwSSSiw? S;:;::SSSSS5;%> INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM ISIill y SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME \ '." . / ' ' '.":'.'. \ : , HISTORIC Virginia City Historic District AND/OR COMMON Same as above HLQCATION ' STREET & NUMBER . - —NOT FOR PUBLICATION . , CITY, TOWN • • .-..-. CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Virginia City . .. , _ . _ VICINITY OF STATE , , CODE COUNTY CODE Nevada : Storey/Lyon HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE DISTRICT ..-.. _ PU&LIC - • -. )LOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X.MUSEUM _|UILDINJ3(S) ^.PRIVATE , . —UNOCCUPIED -XCOMMERCIAL . _PARK, —STRUCTURE r JKeoiH • . _ WORK IN PROGRESS .XEDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE _ SITE . .. ._ - . , PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE JCENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS . —OBJECT . ^_IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED J&3OVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC -,-BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OFPROPERTY NAME various private and public owners STREETS NUMBER CITY, TOWN VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC; S.tOJpey'.. County Court House STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Virginia C|ty___________ Nevada REPRE SENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic.American Buildings Survey. DATE ^FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS' 1100 L Street CITY, TOWN STATE Washington D.C. CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED .^ORIGINAL SITE -KfiOOD —RUINS JCALTERED _MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Virginia City, Nevada, lies almost equidistant between Reno and Carson City, on the face of Mount Davidson, 6,205 feet about sea level. -

Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance This Page Intentionally Left Blank Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance

Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance This page intentionally left blank Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance Richard W. Unger University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia Copyright ᭧ 2004 University of Pennsylvania Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First paperback edition 2007 Published by University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Unger, Richard W. Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance / Richard W. Unger. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8122-1999-9 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8122-1999-6 (pbk : alk. paper) 1. Beer—Europe—History—To 1500. 2. Beer—Europe—History—To 1500—16th century. 3. Brewing industry—Europe—History—To 1500. 4. Brewing industry—Europe—History— 16th century. I. Title. TP577.U54 2003 641.2Ј3Ј0940902—dc22 2004049630 For Barbara Unger Williamson and Clark Murray Williamson This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix List of Tables xi Preface xiii List of Abbreviations xvii Introduction: Understanding the History of Brewing Early Medieval Brewing Urbanization and the Rise of Commercial Brewing Hopped Beer, Hanse Towns, and the Origins of the Trade in Beer The Spread of Hopped Beer Brewing: The Northern Low Countries The Spread of Hopped Beer Brewing: The Southern Low Countries, England, and Scandinavia The Mature Industry: Levels of Production The Mature Industry: Levels of Consumption The Mature Industry: Technology The Mature Industry: Capital Investment and Innovation Types of Beer and Their International Exchange viii Contents Taxes and Protection Guilds, Brewery Workers, and Work in Breweries Epilogue: The Decline of Brewing Appendix: On Classification and Measurement Notes Bibliography Index Illustrations . -

THERESA Mcculla 14Th St

THERESA McCULLA 14th St. And Constitution Ave. NW | MRC 629, PO Box 37012 | Washington, DC 20013-7012 [email protected] | www.theresamcculla.com | @theresamccu EMPLOYMENT Curator, March 2019-present Historian, January 2017-March 2019 American Brewing History Initiative, Division of Work and Industry, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC Arcadia Fellow Colonial North America Project, Harvard Library, Cambridge, MA; June-December 2016 Food Literacy Project Coordinator Harvard University Dining Services, Cambridge, MA; September 2007-August 2010 Open Source Officer Open Source Center, Central Intelligence Agency, Washington, DC; September 2004-August 2007 EDUCATION Harvard University, Cambridge, MA PhD, American Studies, May 2017 Dissertation: “Consumable City: Race, Ethnicity, and Food in Modern New Orleans” Semifinalist, Krooss Prize, best dissertation in business history, Business History Conference, 2017 Honorable Mention, Katz Award, best dissertation in urban history, Urban History Association, 2016 Finalist, Gabriel Prize, best dissertation in American Studies, American Studies Association, 2016 Harvard University MA, History, May 2012 Cambridge School of Culinary Arts, Cambridge, MA Culinary Arts Diploma, Professional Chef’s Program, June 2010 Harvard College, Cambridge, MA BA, magna cum laude, Romance Studies, June 2004 RESEARCH AND TEACHING INTERESTS U.S. history in the 19th and 20th centuries; histories of race, ethnicity, and gender; food and drink history; public history; museum studies; oral history methodology; material culture studies; American Studies; consumer culture McCulla 2 PUBLICATIONS Books “Consumable City: Food and Race in New Orleans” (under contract, University of Chicago Press) Articles “Craft Beer’s Unlikely Alchemist,” Gastronomica 19, no. 4 (Winter 2019): 78-90. Third Place, Best Historical Writing, Awards in Beer Journalism, North American Guild of Beer Writers, 2020 “Fava Beans and Báhn Mì: Ethnic Revival and the New New Orleans Gumbo,” Quaderni Storici 51, no. -

Kellogg International Fellowship Program in Food Systems Fellows' Final Reports September 1989 End-Of-Program Seminar Holiday In

Kellogg International Fellowship Program in Food Systems Fellows' Final Reports September 1989 End-of-Program Seminar Holiday Inn, University Place East LanSing, Michigan U.S.A. Kellogg International Fellowship Program in Food Systems Fellows' Final Reports TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward .........•......................................... iii I. Interest Group I Comprehensive Food And Agriculture Policy . .. 1 Cox, Maximiliano . .. 2 Ledesma, Antonio 5 Lipumba, Nguyuru (not available at press time) Luiselli, Cassio 11 Matus-Gardea, Jaime 15 Tyagi, Davendra . • . .. 19 Wen, Simei 22 II. Interest Group II Agricultural Marketing, Price Policy and Trade . 25 Blandford, David 26 Carter, Colin 29 Paz-Cafferata, Julio 32 Piggott, Roley 35 Quezada, Norberto . 39 Silva, Alvaro 42 III. Interest Group III Programs and Policies to Feed the Poor . 47 Bapna, Shanti 48 Campino, Antonio 51 Dall'Acqua, Fernando 55 Konjing, Chaiwat 59 Mtawali, Katundu ...........•... 62 Muchnik de Rubinstein, Eugenia . 65 Pinnaduwage, Sathyapala . 68 Sampaio, Vony 71 Syarief, Hidayat 74 Uribe-Mosquera, Tomas 79 Vial de Valdes, Isabel 83 IV. Interest Group IV Technology for Food Production and Processing . 87 Badi, Sitt EI Nafar M. 88 Duwayri, Mahmud 91 Makau, Boniface M. 93 Sefa-Dedeh, Samuel . 96 Teri, James M 101 Whingwiri, Ephrem 105 Van, Rui-zhen 111 11 FORWARD This volume is a collection of the final reports of the Kellogg International Fellows in Food Systems on their individual project activities over the past three years. It provides an overview of the substantial accomplishments of the Fellows in the expansion and application of knowledge to improve food systems in their respective countries and regions. Equally important has been the growth of the Fellows themselves in the broadening and deepening of their understanding of food systems and expanded leadership capabilities through sharing of their experiences with each other. -

NATIONAL CONFERENCE April 12 -15 , 2017

NATIONAL CONFERENCE April 12th-15th, 2017 Marriott Marquis Marina San Diego, CA Jennifer Loeb PCA/ACA Conference Coordinator Joseph H. Hancock, II PCA/ACA Executive Director of Events Drexel University Brendan Riley PCA/ACA Executive Director of Operations Columbia College Chicago Sandhiya John Editor Wiley-Blackwell Copyright 2017, PCA/ACA Additional information about the PCA/ACA available at pcaaca.org Table of Contents President’s Welcome 2 Conference Administration 3 Area Chairs 3 Officers 15 Board Members 15 Program Schedule Overview 18 Special Events & Ceremonies 18 Exhibits & Paper Table 20 2017 Ray and Pat Browne Award Winners 22 Special Guests 23 Schedule by Topic Area 24 Daily Schedule Overview 69 Full Daily Schedule 105 Index 244 Floor Maps 292 Dear PCA/ACA Conference Attendees, Welcome! We are so pleased that you have joined us in San Diego for what promises to be another stimulating and enriching conference. In addition to the hundreds of sessions available, a meeting highlight will be an address from our Lynn Bartholome Eminent Scholar awardee, David Feldman of Imponderables fame. As always, there will be plenty of times and spaces to connect with old friends and make new ones: area interest sessions, coffee breaks, film screenings, and special themed events and roundtables. Be sure to take advantage of the networking and scholarly connection opportunities in the book exhibit room. And don’t forget about Friday’s all conference reception! Graduate students and new-comers, we welcome you especially. We hope you will find this a professional home for years to come. Finally, as you depart San Diego at week’s end, be sure to mark your calendars for our Indianapolis meeting, March 25 – April 1, 2018. -

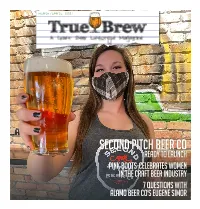

Second Pitch Beer Co

march/April 2021 SECOND PITCH BEER CO READY TO LAUNCH PINK BOOTS-CELEBRATES WOMEN IN THE CRAFT BEER INDUSTRY 7 QUESTIONS WITH ALAMO BEER CO'S EUGENE SIMOR MISSION STATEMENT At True Brew Magazine, craft beer is our lifestyle. From the places we visit to the food we eat and even the music that we listen to, craft beer always seems to play a role. For the craft beer brewers, retailers, and consumers we would like to use our combined knowledge to enhance the appreciation of the local craft beer experience. ERIK BUDRAKEY JENNIFER PEYSER True Brew Magazine’s mission is to be recognized by the Craft Beer Breweries, Retailers, and Consumers as the premier craft beer magazine in the region. Our goal is deliver to the consumer all of the latest craft beer news, unique brewery offerings, beer Introducing dinners, events, festivals, and special releases in the San Antonio region and beyond. Through our digital magazine we will reach more than 30,000 local craft beer consumers, doubling our efforts through our website and social media campaigns. Our goal is to introduce the consumer to the passionate people who create these unique brews (and spirits)—take them on As we enter our fifth year of publishing True Brew Magazine, there a virtual tour of local, regional, and national breweries, are more than 350 breweries across Texas, including 30ish in offering a behind-the-scenes look and appreciation of the San Antonio Region. Throw in surrounding better-beer-bars, their operations by providing a first-hand feel for their craft distilleries, and wineries—and we’ve got ourselves quite the culture and unique local products. -

Women in the Livery High Civic Office in the City

Women in the Livery and High Civic Office in the City City of London Women in the Livery and High Civic Office in the City including Lady Masters Association and City Consorts A Research Paper by Erica Stary, LLM, FTII, ATT, TEP Past Master Tax Adviser, Past Master Plumber and Upper Warden Elect Tin Plate Workers alias Wire Workers © Erica Stary January 2021 Women in the Livery and High Civic Office in the City FOREWORD It’s a privilege to be asked to write the foreword for this new paper on Women in the Civic City and Livery. What started as a short research project in lockdown on the Lady Masters Association has turned into a comprehensive and informative paper on how the role of women in City Civic life has evolved since the Middle Ages. It’s easy to forget how quickly the livery has changed in this regard. In 1983, when the first female Lord Mayor, Dame Mary Donaldson was elected, more than half of the livery companies were not open to women on equal terms as men. At the turn of the millennium, more than a quarter still did not allow equal admittance. Now, at long last, in 2020, all City livery companies and guilds accept women on equal terms with men, making this a timely moment for this research paper to be published. As the paper reminds us, women have had a long and significant impact in civic and livery life in the last thousand years. Many Medieval guilds were reliant on the skilled work of women and many buildings only came into the possession of the Livery or the City Corporation, such as the former Bricklayers Hall or Columbia Market, through acquisitions and donations from women. -

Land Et Al. Final Formatted

Back to the Brewster: Craft brewing, gender and the dialectical interplay of re- traditionalisation and innovation Chris Land, Neil Sutherland, Scott Taylor The significance of gender within contemporary craft work is frequently acknowledged, but rarely analysed in empirical depth. In this chapter we explore the experiences of women working in the craft brewing industry, paying particular attention to how the recent expansion in craft beer production and consumption is underpinned by a masculinised and patriarchal notion of re- traditionalisation. This is made apparent in the masculinities evident in persistently reproduced structures, aesthetics, marketing and attitudes surrounding craft production in this sector. Imprinting patriarchy: Gender and craft work Although some of the craft practices discussed in this book are symbolically gendered as female, the dominant cultural image of the skilled artisan/craft-worker remains predominantly male. The persistence of this masculine coding is integral to how craft has intersected with capitalism. In Cynthia Cockburn’s (1983) classic study of technological change in the printing industry, Brothers, she highlighted the interactions between capitalism and patriarchy in shaping the practice and fate of skilled printers. In traditional printing, a forme had to be assembled by hand, with the printer selecting lead-block type from cases, with printers assembling them according to the text but back to front. This required a high degree of literacy combined with an aesthetic sensibility for layout and when to split words. It also required a degree of physical strength to handle the final bound forms, as well as responsibility for maintaining the type. Proficiency in all aspects of this production process was what enabled the apprentice printer to lay claim to the identity of a master crafter.