The Natural Learning Process and Its Implications for Trombone Pedagogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Arnold Jacobs's Teaching on Canadian Tuba

Song and Wind in Canada: The Impact of Arnold Jacobs’s Teaching on Canadian Tuba Pedagogues by Jonathan David Rowsell A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Faculty of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Jonathan David Rowsell 2018 Song and Wind in Canada: The Impact of Arnold Jacobs’s Teaching on Canadian Tuba Pedagogues. Jonathan David Rowsell Doctor of Musical Arts Faculty of Music University of Toronto 2018 Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate the impact of Arnold Jacobs on the pedagogical approaches of prominent tuba teachers in Canada. Nine tuba teachers from different Canadian universities participated in this study. Each participant was interviewed digitally using Skype or FaceTime and asked nine questions designed to understand their personal pedagogical approach and how it relates to Arnold Jacobs. These questions cover important pedagogical ideas including sound concept, breathing, articulation, and embouchure. Arnold Jacobs is considered to be one of the most influential brass pedagogues in history. His method of teaching, referred to as Song and Wind, is a pedagogical concept frequently implemented in contemporary applied tuba teaching. The interview findings of this study demonstrate that the Arnold Jacobs legacy is very present in Canadian tuba pedagogy. The approaches to articulation and sound concept demonstrated by the interview subjects are consistently Jacobs inspired. The approaches to breathing and embouchure, however, are much more varied. Although these elements are not as tightly embedded in the Jacobs pedagogical ii approach, the results of the study demonstrate that the majority of the interview subjects are fully aware of the ways in which their current approaches have been adapted. -

Linda Yeo Leonard Recordings and Critical Listening Masterclass

Linda Yeo Leonard Recordings and Critical Listening Masterclass “World class players do not just happen – their talents are forged in the dual furnaces of determination and diligence.” -Edward Kleinhammer, former bass trombonist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (1940-1985) Becoming the best player you can will take hard work and determination. But if you work to become 1%-3% better every week you play your horn, just think how much better you could be in 6 months . a year. Wow- that would be exciting! I can’t stress the importance of listening to great recordings- I picked up many things from my father playing trombone in my house growing up. Many of you probably don’t have a parent who plays an instrument professionally. That’s fine- there are many excellent recordings out there of great musicians playing your instruments. Trombone: A Gala Festival (the Canadian Staff band, with Alain Trudel, Canadian trombone virtuoso- the best and fastest “Blue Bells of Scotland” I’ve ever heard! Proclamation, Two of a Mind, The Essential Rochut, Cornerstone, Take 1, and the New England Brass Band recordings on my dad’s website: www.yeodoug.com. Bass trombone solos and trombone duets with brass band, solos, recordings of him playing when he was younger, and rocking brass band recordings with him conducting) A New At Home and Experiments in Music, by Norman Bolter, my dad’s co-worker- former 2nd trombonist in the BSO At the End of the Century- Joe Alessi, principal trombonist of the NY Philharmonic Fancy Free, by Blair Bollinger, bass trombonist in the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra Trombones De Costa Rica- rocking trombone 4ets Bonetown with Michael Davis and Bill Reichenbach The Legacy of Emory Remington and the Eastman Trombone Choir Euphonium: World of the Euphonium 5 by Stephen Mead CDs by the Childs Brothers American Variations by Brian Bowman Leonard Falcone and His Baritone Volumes 1-4 (Euphonium CDs suggested by Mr. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Program, January 15, 1948

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA PROGRAM, JANUARY 15, 1948 ARNOLD JACOBS, wielder of the tuba, Was born in Philadelphia in 1915. His father having "wanderlust", he spent the first fourteen years of his life travelling back and forth from Philadelphia to various points in California. His grandfather being a violinist and his mother a pianist, he, the third generation, become a musical black sheep when he took to a brass instrument. This was at the age of eleven when he became "bugler" in the Junior Boy Scouts. His mother wanted him to be a pianist but he finally discouraged these aspirations "by going for piano lessons with bandages on his fingers." From being bugler his next step was the trumpet, then the trombone and finally, because he lost his trombone enroute to California, the school band master offered to let him play tuba in the band. On his return to Philadelphia a few months later, at the age of 15, he was given a scholarship at the Curtis Institute of Music. After graduating from Curtis, he played for two seasons with Fabien Sevitsky in the Indianapolis Symphony. From there he went to the Pittsburgh Symphony and played for five seasons under Fritz Reiner. In 1941 he toured the country with Leopold Stokowski and the All-American Youth Orchestra, In 1944 he joined the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. In 1937 he married a girl from Chicago who was dancing in the show he was playing in Atlantic City, N. J. at the R.C.A. convention ; they now have a nine-year-old son "who", says his dad, "plasters up his lips every time I try to give him a tuba lesson." His hobbies are deep sea fishing and photography and playing "jazz" on a bass fiddle. -

Curriculum Vitae Luis F

Curriculum Vitae Luis F. Fred E-address: [email protected] YouTube Channel: Luis Fred Trombon, LinkedIn: Luis Fred Office: (407) 823-5966 Orchestral Appointments • Puerto Rico Symphony Orchestra, PR (1998-2017), Principal Trombone. o Conductors: Maximiano Valdés, Rafael Frübeck de Burgos, Sergiu Comissiona, Giancarlo Guerrero, Yoav Talmi, Guillermo Figueroa, Luis Biava, Eugene Kohn, Roselín Pabón, Rafael E Irizarry. • Springfield Symphony Orchestra, MA (1996-1998), Second Trombone o Conductor: Mark Russell Smith • Seville Symphony Orchestra, Spain (1992-1994), Co-Principal Trombone o Conductors: Yuri Termirkanov, Vjekoslav Sutej • Madrid Symphony Orchestra, Spain (1990-1992), Co-Principal Trombone o Conductors: Antoni Ros Marbá, Rafael Frübeck de Burgos, Miguel A. Gómez Martínez, Miguel Roa Orchestral Experience-United States Selected performances • Chicago Symphony Orchestra, (2015-present), substitute tenor trombone o Conductors: Bernard Haitink, Jaap van Zweden, Esa Pekka-Salonen, Charles Dutoit, Donald Runnicles. • Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, (Fall 2016), substitute tenor trombone o Conductors: Robert Spano, Donald Runnicles, Michael Krajewski, Joseph Young • Chicago Music of the Baroque, (2014, 2017), substitute trombone o Conductors: Jane Glover, Nicolas Kraemer o Review Mozart Requiem: http://chicagoclassicalreview.com/2014/10/kraemer-opens-mob-season-with- well-tempered-mozart/ • New York Philharmonic, (1996-2003), utility trombone o Conductors: Kurt Masur, Charles Dutoit, Eji Oue • Houston Symphony Orchestra (2002), substitute trombone o Conductor: Christoph Eschenbach • Los Angeles Philharmonic, (1998), substitute trombone o Conductor: Esa Pekka-Salonen Casals Festival Selected performances. • Metales del Festival Casals, (Feb 2011), contractor and soloist. o Puerto Rico premiere of Derek Bourgeois Osteoblast for Trombone Octet and of José Pujals Bomba para Metales. Rafael E Irizarry, conductor • Saint-Saens Symphony no. -

CSO Program Oct 78 Arnold Jacobs, Who Has Been the Chicago

CSO Program Oct 78 Arnold Jacobs, who has been the Chicago Symphony's tuba player since 1944 plays bugle, trumpet and trombone and considered becoming a singer before he decided to become a tuba player. He entered Curtis Institute of Music in his native city of Philadelphia as a fifteen-year-old scholarship student and graduated in 1937. He was engaged as the Indianapolis Symphony's tuba player under Fabien Sevitsky for two seasons and then took the same post with the Pittsburgh Symphony while Fritz Reiner was conductor. From Pittsburgh he came to Chicago. He toured the country in 1941 with Leopold Stokowski and the AII- American Youth Orchestra and was loaned to the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra in the spring of 1949 for their England-Scotland tour. In June, 1962 he had the honor of being the first tuba player to be invited to play the Festival Casals under Pablo Casals in San Juan. Puerto Rico. Mr. Jacobs is a member of the Chicago Symphony Brass Quintet. and teaches tuba at Northwestern University School of Music and for the Civic Orchestra. His former tuba students in other orchestras include Tony Hanks, Minneapolis; Harold McDonald, Pittsburgh; Dan Corrigan, Indianapolis; Charles Guse. Lyric Opera; Don Heeren, Denver; Ron Bishop, San Francisco; John Taylor, Buffalo; John Kalnins, Birmingham; and Richard Schneider, Israel Symphony. Mr. Jacobs maintains an interest in the biological sciences, especially as they apply to tone production in wind instruments. He is a widely-known lecturer and clinician in the field of wind instruments and has appeared throughout the country. -

Please Click for the ITEC 2014 Schedule

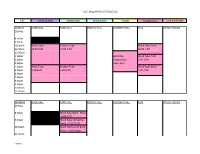

ITEC 2014 MASTER SCHEDULE KEY: warm up class masterclass presentation recitals competitions tuba ensembles SUNDAY AUER HALL FORD HALL RECITAL HALL SWEENEY HALL MAC OTHER VENUES 18-May 8:00am 9:00am 10:00am Artist Euph Student Euph Mock Tuba Band 11:00am 10:00-3:00 10:00-3:00 10:00-1:00 12:00pm 1:00pm Ensemble Mock Tuba Orch 2:00pm Competition 1:30-3:30 3:00pm noon-5pm 4:00pm Artist Tuba Student Tuba Mock Euph Band 5:00pm 3:30-8:30 3:30-8:30 4:00-7:00 6:00pm 7:00pm 8:00pm 9:00pm 10:00pm 11:00pm MONDAY AUER HALL FORD HALL RECITAL HALL SWEENEY HALL MAC OTHER VENUES 19-May 8:00am Mock Tuba Band - Finals - 8:00-9:00 9:00am Mock Tuba Orchestra - Finals - 9:30-10:30 10:00am Mock Euphonium Band - Finals - 11:00-noon 11:00am 1 of 13 ITEC 2014 MASTER SCHEDULE 12:00pm Opening Ceremony & Concert with Tennessee Tech Tuba Ensemble - noon to 1:30 1:00pm General Membership meeting to immediately follow the opening ceremony 2:00pm Presentation - Gene Presentation - Ted Pokorny & Anthony Cox - Beyond Music - Kniffen - Concepts of 2:30-3:30 Sound and Balance - Does the BBb Tuba Sound Have a Place in an American Symphony Orchestra? - 2:30-4:00 3:00pm 4:00pm Tuba Ensemble - Recital - Kazuhiro Masterclass - Jeff Ensemble University of Michigan - Nakamura & Aaron Nelson on Fearless Competition Finals - 4:30-4:55 Tindall - 3:45 - 4:45 Performance - 3:45 - 4:00-6:00 4:45 5:00pm Recital - Boreas Quartet Presentation - Sam & Matthew van Emmerik - Pilafian & Patrick 5:00 - 6:00 Sheridan - The Breathing Gym - 5:00 - 6:00 6:00pm Tuba Ensemble - Louisiana State University -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Music Director

Program One HundRed TWenTy-FiRST SeASOn Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Tuesday, May 15, 2012, at 1:30 Thursday, May 17, 2012, at 8:00 Jaap van Zweden Conductor gene Pokorny Tuba Shostakovich Chamber Symphony for Strings in C Minor, Op. 110a Largo— Allegro molto— Allegretto— Largo— Largo Vaughan Williams Tuba Concerto Prelude: Allegro moderato Romanza: Andante sostenuto Finale (Rondo all tedesca): Allegro Gene POkORny IntermISSIon Beethoven Symphony no. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 Poco sostenuto—Vivace Allegretto Presto Allegro con brio This evening’s concert is generously sponsored in part by the Audrey Love Charitable Foundation. Wednesday, May 16, 2012, at 6:30 (Afterwork Masterworks, performed with no intermission) Jaap van Zweden Conductor gene Pokorny Tuba Shostakovich Chamber Symphony for Strings in C Minor, Op. 110a Vaughan Williams Tuba Concerto in F Minor Beethoven Symphony no. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is grateful to WBBM Newsradio 780 and 105.9 FM for its generous support as the media sponsor for the Afterwork Masterworks series. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommentS by PHiLLiP HuSCHeR Dmitri Shostakovich Born September 25, 1906, Saint Petersburg, Russia. Died August 9, 1975, Moscow, Russia. Chamber Symphony for Strings in C minor, op. 110a n the summer of 1960, in just three days, is his Eighth, IShostakovich went to Dresden to and it is one of the most powerful write the score for a new film by the and personal works of twentieth- director Lev Arnshtam. -

Kidsbook © Is a Publication of the Negaunee Music Institute

KIDS�OOK CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SYMPHONIC SUPERHEROES! CSO FAMILY MATINEE SERIES November 5, 2016, 11:00 & 12:45 CSO SCHOOL CONCERTS November 7, 2016, 10:15 & 12:00 312-294-3000 | CSO.ORG | 220 S. MICHIGAN AVE. | CHICAGO SYMPHONIC SUPERHEROES CSO FAMILY WELCOME!WELCOME! MATINEE SERIES CONCERTS November 5, 2016 11:00 & 12:45 SCHOOL CONCERTS November 7, 2016 10:15 & 12:00 What is courage, and why do we need it? To have courage means PERFORMERS we are brave—and we need to be Members of the brave for lots of things, like learning Chicago Symphony Orchestra how to ride a bike, going to school Tania Miller, for the first time, standing up for a conductor friend, and sticking with something that is difficult. PROGRAM INCLUDES SELECTIONS FROM What do you think courage sounds like? Do certain pieces of music Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 4, need more courage to perform Mvt. 4 than others? Does it take courage to compose music? What acts of McTee Circuits courage have helped everyday musicians become the superheroes Rimsky-Korsakov of the CSO? Sheherazade Copland Appalachian Spring Kernis ABOUT THE PROGRAM Musica Celestis This Symphonic Superheroes concert Stravinsky explores the ways that courage is necessary Infernal Dance from The Firebird for the amazing musicians of the Chicago Shostakovich Symphony Orchestra to perform, for Symphony No. 10, composers to create and for audiences to Mvt. 2 listen to music. Beethoven List three ways you think musicians need Symphony No. 9 courage to perform. 1. 2. 3. 2 CSO Family Matinee series / CSO School Concerts / SYMPHONIC SUPERHEROES CourageousCourageous THE COURAGE TO DO MusiciansMusicians SOMETHING DIFFICULT Did you know it takes a lot of courage to play fast notes, or even just to play the right notes at the right time? As you listen to Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. -

Arnold Jacobs Obitua

Arnold Jacobs Arnold Jacobs, former tubist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Arnold Jacobs, former principal tuba of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra passed away suddenly in his home at the age of eighty-three the morning of October 7, 1988. He is survived by his wife of over 60 years, Gizella Valfy Jacobs, son Arnold Dallas Jacobs, his wife Dorothy, grandson Robin Jacobs, and great grandson Christopher Jacobs. Others include nephew Allan Young, his wife Elizabeth, grand nephew Carl Young, grand niece Christina Cathcart, her husband Joseph, and several grand nephews and nieces. Mr. Jacobs was born in Philadelphia on June 11, 1915 but raised in California. The product of a musical family, he credits his mother, a keyboard artist, for his initial inspiration in music, and spent a good part of his youth progressing from bugle to trumpet to trombone and finally to tuba. He entered Philadelphia's Curtis Institute of Music as a fifteen-year-old on a scholarship and continued to major in tuba. After his graduation from Curtis in 1936, he played two seasons in the Indianapolis Symphony under Fabien Sevitzky. From 1939 until 1944 he was the tubist of the Pittsburgh Symphony under Fritz Reiner. In 1941 Mr. Jacobs toured the country with Leopold Stokowski and the AII-American Youth Orchestra. His was a member of the Chicago Symphony from 1944 until his retirement in 1988. During his forty-four year tenure with the Chicago Symphony, he took temporary leave in the spring of 1949 to tour England and Scotland with the Philadelphia Orchestra. He was on the faculty of Western State College’s Music Camp at Gunnison, Colorado during the early 1960’s. -

Ebook Download Also Sprach Arnold Jacobs Kindle

ALSO SPRACH ARNOLD JACOBS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Compiled by Bruce Nelson | 104 pages | 01 Jun 2006 | Windsong Press Ltd | 9783981245622 | English | none Also Sprach Arnold Jacobs PDF Book Jacobs presented clinics in Tokyo. Hickeys Music Center. Jeremy Smith marked it as to-read May 30, Strings are represented with a series of five digits representing the quantity of each part first violin, second violin, viola, cello, bass. Even if it were all known, it would be impossible to reduce to writing all of the advice Arnold Jacobs gave to thousands of students over a period of almost 70 years. Jan Schaap rated it it was amazing Jul 14, Jacobs had the reputation as both the master performer and master teacher. Refresh and try again. The bracketed numbers tell you how many of each instrument are in the ensemble. Melissa marked it as to-read Jan 27, Samuel is currently reading it Feb 16, He taught tuba at Northwestern University and all wind instruments in his private studio. Multiples, if any, are not shown in this system. Example 3 - MacKenzie: a fictional work, by the way. Note also that the separate euphonium part is attached to trombone with a plus sign. Other Required and Solo parts follow the strings:. Following many of the titles in our Brass Ensemble catalog, you will see a set of five numbers enclosed in square brackets, as in this example:. Each chapter deals with one central aspect of brass playing. The set of numbers after the dash represent the Brass. This is standard orchestral nomenclature. In addition, there are often doublings in the Trumpet section - Piccolo and Flugelhorn being the most common. -

Version FINAL OCTUBRE

Kurs: CA1005 Självständigt arbete 30 hp 2017 Master Program Degree Project, 120 hp Institution of Classical Music Handledare: Katarina Ström-Harg Salvador López Pérez Who helped to develop the role of the tuba as a solo instrument? Skriftlig reflektion inom självständigt arbete Till dokumentationen hör även följande inspelning: xxx ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to find out the process carried out by many people to achieve a solo role for the tuba. It also explains which individuals people helped the development of the instrument so as how different composers have contributed to the music field and especially to the evolution and growth of the tuba in the last century. In the musical part, the thesis talks about different standard tuba pieces and their importance. Key words: Tuba, brass instrument, music, first works tuba, solo pieces, analysis for interpretation, tuba pedagogy, artistic research. Table of contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................1 1.1 Context .........................................................................................................................................1 2. Background ........................................................................................................3 3. Aim ......................................................................................................................4 4. Method ................................................................................................................4 -

ITEC Program Book

ITEC 2019 Program Addendum Voxman Building Notes - The Voxman School of Music’s facilities will be open every day from 7am – 10pm for the duration of the conference - The registration desk will be available on the 2000 level in the Pearl West Lobby from 8am-8pm for the duration of the conference - Instrument storage will be available in the Stark Opera Theater (0151) from Tuesday through Saturday, 8am-8pm and for 30 minutes after the end of the evening concerts o Exception: instrument storage will close at 4:30pm on Thursday to allow volunteers time to prepare for and attend the Banquet - No instruments or cases are allowed in the Concert Hall or Recital Hall audience during performances - No food or drink (except water) in any classroom or performance space - Lessons with students under 18 years of age require a parent or guardian in the room Schedule Corrections Monday, May 27 Correction 9:00am – Recital Hall (2301) – Competition: Mock Band - Tuba Incorrectly listed as taking place in Stark Opera Theater (pg. 17, pg. 27) Correction 9:00am – Stark Opera Theater (0151) – Competition: Electronics Incorrectly listed as starting at 5:00pm (pg. 27) Correction 3:00pm – Recital Hall (2301) – Competition: Young Artist Euphonium Final Round Incorrectly listed as Artist Euphonium Final Round (pg. 27) Correction 3:30pm – Concert Hall (2101) – Competition: Ensemble Final Round Incorrectly listed as starting at 3:00pm (pg. 17, omitted on pg. 27) Tuesday, May 28 Cancellation 9:00am – James Dixon Room (0002) – Presentation: Samuel Adler – David Saltzman (pg. 18, 32) Correction 2:00pm – James Dixon Room (0002) – Presentation: Young at Heart – Velvet Brown and Roger Bobo (pg.