INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hypertext Semiotics in the Commercialized Internet

Hypertext Semiotics in the Commercialized Internet Moritz Neumüller Wien, Oktober 2001 DOKTORAT DER SOZIAL- UND WIRTSCHAFTSWISSENSCHAFTEN 1. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Wolfgang Panny, Institut für Informationsver- arbeitung und Informationswirtschaft der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien, Abteilung für Angewandte Informatik. 2. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dr. Herbert Hrachovec, Institut für Philosophie der Universität Wien. Betreuer: Gastprofessor Univ. Doz. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Veith Risak Eingereicht am: Hypertext Semiotics in the Commercialized Internet Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Sozial- und Wirtschaftswissenschaften an der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien eingereicht bei 1. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Panny, Institut für Informationsverarbeitung und Informationswirtschaft der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien, Abteilung für Angewandte Informatik 2. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dr. Herbert Hrachovec, Institut für Philosophie der Universität Wien Betreuer: Gastprofessor Univ. Doz. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Veith Risak Fachgebiet: Informationswirtschaft von MMag. Moritz Neumüller Wien, im Oktober 2001 Ich versichere: 1. daß ich die Dissertation selbständig verfaßt, andere als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel nicht benutzt und mich auch sonst keiner unerlaubten Hilfe bedient habe. 2. daß ich diese Dissertation bisher weder im In- noch im Ausland (einer Beurteilerin / einem Beurteiler zur Begutachtung) in irgendeiner Form als Prüfungsarbeit vorgelegt habe. 3. daß dieses Exemplar mit der beurteilten Arbeit überein -

Interpretation in Recent Literary, Film and Cultural Criticism

t- \r- 9 Anxieties of Commentary: Interpretation in Recent Literary, Film and Cultural Criticism Noel Kitg A Dissertàtion Presented to the Faculty of Arts at the University of Adelaide In Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 7994 Nwo.rà"o\ \qq5 l1 @ 7994 Noel Ki^g Atl rights reserved lr1 Abstract This thesis claims that a distinctive anxiety of commentary has entered literary, film and cultural criticism over the last thirty years/ gathering particular force in relation to debates around postmodernism and fictocriticism and those debates which are concerned to determine the most appropriate ways of discussing popular cultural texts. I argue that one now regularly encounters the figure of the hesitant, self-diiioubting cultural critic, a person who wonders whether the critical discourse about to be produced will prove either redundant (since the work will already include its own commentary) or else prove a misdescription of some kind (since the criticism will be unable to convey the essence of , say, the popular cultural object). In order to understand the emergence of this figure of the self-doubting cultural critic as one who is no longer confident that available forms of critical description are adequate and/or as one who is worried that the critical writing produced will not connect with a readership that might also have formed a constituency, the thesis proposes notions of "critical occasions," "critical assemblages," "critical postures," and "critical alibis." These are presented as a way of indicating that "interpretative occasions" are simultaneously rhetorical and ethical. They are site-specific occasions in the sense that the critic activates a rhetorical-discursive apparatus and are also site-specific in the sense that the critic is using the cultural object (book, film) as an occasion to call him or herself into question as one who requires a further work of self-stylisation (which might take the form of a practice of self-problematisation). -

Poststructuralism in English Classrooms: Critical Literacy and After

1 Poststructuralism in English classrooms: Critical literacy and after Bronwyn Mellor & Annette Patterson This paper was published in a slightly different form in: International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, Vol 17, No 1, p.85-102 (2004). Copyright 2004 Taylor & Francis 2 Poststructuralism in English classrooms: Critical literacy and after Abstract This paper explores the effects of poststructuralism on the work of two English teachers and writers of classroom texts. It traces aspects of their theoretical and practical engagement with poststructuralism from an initial acceptance of what appeared to promise the possibility of a truly critical practice through ideology critique to a stance that endeavours to include a consideration of the emergence of English pedagogy as well as theories about language and meaning. Current understandings of reading in English classrooms have moved away from the belief that the interpretation of literature is purely a matter of personal response. Instead, it has been argued during recent decades that reading is a socially, culturally and historically located practice. In part, this change is an inheritance from British Cultural Studies which, informed by political and cultural theory, influenced English in seemingly radical ways in the 1970’s and 80’s. During this period ‘theory’ – especially postructuralist theory – effected changes at every level of English teaching. Challenges to ideas about what constituted a student reader, a classroom text and an interpretation resulted in a re-formation of English in high schools. This re-formation included shifts in emphases away from the individual reader’s personal response to texts toward the idea of subject positioning through textual practices, a review of the concept of interpretation, a focus on the concept of multiple readings, a deconstruction of the opposition between 3 high culture and popular culture and an embracing of the concepts of text, textuality and intertextuality. -

Post-Structuralism and Radical Politics Specialist Group of The

Post-Structuralism & Radical Politics post-structuralism & radical politics Specialist Group of the PSA Group Convenor Alan Finlayson Department of Political Theory and Government University of Wales Swansea Singleton Park Swansea SA2 8PP Email: [email protected] Newsletter Editor James Martin newsletter Department of Social Policy & Politics Goldsmiths College University of London no. 2, june 2000 New Cross London SE14 6NW Email: [email protected] Visit our web site: http://homepages.gold.ac.uk/psrpsg/ where this Newsletter is available as a PDF document editorial identity, politics and so on. This can be put down Alan Finlayson to watching too many Open University programmes as a teenager and to the common I don’t need to tell anyone reading this about the tendency of straight, white, middle-class boys to disciplinary technologies that are rapidly extending appropriate the struggles of Latin Americans or themselves into our workplaces. QAA and the urban community theatre groups. But, whatever ‘benchmarking’ of subject specifications are a my subjective motivations the objective necessity headache for all of us. The ease with which they of opening up the social to wider ranging can be employed as textbook examples of contestation persists. We can do this in our ‘governmentality’ hardly compensates for the everyday lives as customers of the UK state but we increased workload they demand. should also be doing it in our work lives and in our teaching. But where there is normalisation there is also the opportunity for subversion. The QAA Coming from a sociology/cultural studies sort of benchmarking statement for politics and background I was somewhat surprised to discover international relations is satisfyingly vague. -

A Post-Holocaust Reading of Jewish Heroism in Bernard Malamud's The

Title: A Post-Holocaust Reading of Jewish Heroism in Bernard Malamud’s The Fixer, “Man in the Drawer,” and “An Apology” Author: Sajjad Mahboobi Affiliation: Islamic Azad University, Karaj Branch Year:2015 Abstract: This thesis has two major purposes: to examine the concept of Jewish heroism in Bernard Malamud’s selected works, and to demonstrate that despite denying it, the author is foremost concerned with Jewish, rather than universal, issues. It is argued that the main characters of Malamud’s fiction, especially in the discussed narratives, portray heroism through resistance, morality, and the responsibility they accept toward their people, while they suffer inevitably and arouse emotion in the reader on miseries and pains of Jews. In light of a truth- oriented historicist approach, the researcher argues that Malamud’s characters are time-bound and benefit from the postwar Holocaust-saturated America and the considerable sympathy that Jews drew especially in those years. While these characters associate the non-Jewish reader mainly with two things, Jew the innocent and the alleged Holocaust, they help American Jews, in particular, rise again from the so-called Auschwitz ashes and free from Jew-the-victim mentality, intensified by the Holocaust propaganda, through displaying heroism of resistance. They also help revive qualities of Jewishness that were fading in the increasingly assimilated postwar perio Keywords: : Post-Holocaust Jewish American fiction, Jewish suffering, Jewish heroism, Jew-the-victim mentality References: Aarons, Victoria. “Malamud, Bernard.” The Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Fiction. Gen. ed. Brian W. Shaffer. 3 vols. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. 681-684. PDF. Abrams, M. -

Are a Way of Understanding and Handling Empirical Materials and Thoughts

Volume 20, No. 2, Art. 2 May 2019 The "Studies in Ethnomethodology" Are a Way of Understanding and Handling Empirical Materials and Thoughts Eric Laurier in Conversation With Hannes Krämer, Dominik Gerst & René Salomon Key words: Abstract: In the following conversation Eric LAURIER talks about the role of ethnomethodology's ethnomethodology; foundational account—the "Studies in Ethnomethodology" (GARFINKEL, 1967)—within the UK and methodology; the influence of the book on his own research as well as on human geography, mobility studies, mobility; actor- actor-network-theory, and a general social science methodology. He therefore underlines the network-theory; peculiar focus of GARFINKEL on the everyday, his non-ironic position towards member's practices, materiality; and the plurivocality of the book. Giving an elaborated account on the methodological challenges everyday life with an ethnomethodological approach including video recordings he differentiates between the video as a research tool and video usage as a member's practice. LAURIER demonstrates the inspiring and initiating content of the studies as well as its limits. By doing so he can show the prolific quality for current research fields like the study of mobility and movement, the question of space and place, and the role of the "Studies in Ethnomethodology" as a political text. Table of Contents 1. Conversations on Ethnomethodology Often Start With "How Did You Get Into This?" 2. This Stylistics of Writing has a Positive Quality 3. GARFINKEL's Peculiar Take on the Everyday 4. Reading the Book 5. Theory and Methodology Are Interwoven 6. It Is a Book You Always Return to 7. -

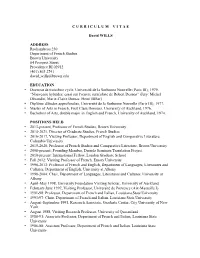

C U R R I C U L U M V I T a E David WILLS ADDRESS Rochambeau

C U R R I C U L U M V I T A E David WILLS ADDRESS Rochambeau 230 Department of French Studies Brown University 84 Prospect Street Providence RI 02912 (401) 863 2741 [email protected] EDUCATION • Doctorat de troisième cycle, Université de la Sorbonne Nouvelle (Paris III), 1979. “Nouveaux hybrides: essai sur l’œuvre surréaliste de Robert Desnos” (Jury: Michel Décaudin, Marie-Claire Dumas, Henri Béhar) • Diplôme d'études approfondies, Université de la Sorbonne Nouvelle (Paris III), 1977. • Master of Arts in French, First Class Honours, University of Auckland, 1976. • Bachelors of Arts, double major in English and French, University of Auckland, 1974. POSITIONS HELD • 2013-present, Professor of French Studies, Brown University • 2014-2021, Director of Graduate Studies, French Studies • 2016-2017, Visiting Professor, Department of English and Comparative Literature, Columbia University • 2015-2020, Professor of French Studies and Comparative Literature, Brown University • 2008-present: Founding Member, Derrida Seminars Translation Project • 2010-present: International Fellow, London Graduate School • Fall 2012: Visiting Professor of French, Emory University • 1998-2013: Professor of French and English, Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures, Department of English, University at Albany • 1998-2004: Chair, Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures, University at Albany • April-May 1998, University Foundation Visiting Scholar, University of Auckland • February-June 1997, Visiting Professor, Université de Provence (Aix-Marseille -

Semiotics the Basics, Second Edition

1 2 SEMIOTICS 3 4 THE BASICS 5 6 7 8222 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Following the success of the first edition, Semiotics: the Basics has 8 been revised to include new material on the development of semi- 9 otics from Saussure to contemporary socio-semiotics. This second 20 edition is fully updated with an extended index, glossary, and further 1222 reading section. Using jargon-free language and lively up-to-date 2 examples, this book demystifies this highly interdisciplinary subject 3 and addresses questions such as: 4 5 • What is a sign? 6 • Which codes do we take for granted? 7 • What is a text? 8 • How can semiotics be used in textual analysis? 9 • Who are Saussure, Peirce, Barthes and Jakobson – and why 30 are they important? 1 2 The new edition of Semiotics: the Basics provides an interesting and 3 accessible introduction to this field of study, and is a must-have for 4 anyone coming to semiotics for the first time. 5 6 Daniel Chandler is a Lecturer in the department of Theatre, Film 7222 and Television Studies at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth. ALSO AVAILABLE FROM ROUTLEDGE LANGUAGE: THE BASICS (SECOND EDITION) R. L. TRASK PSYCHOLINGUISTICS: THE KEY CONCEPTS JOHN FIELD KEY CONCEPTS IN LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS R.L. TRASK THE ROUTLEDGE COMPANION TO SEMIOTICS AND LINGUISTICS PAUL COBLEY COMMUNICATION, CULTURE AND MEDIA STUDIES: THE KEY CONCEPTS JOHN HARTLEY 1 2 SEMIOTICS 3 4 5 6 THE BASICS 7 8222 9 SECOND EDITION 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 20 1222 Daniel Chandler 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 6 7222 First published 2002 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Reprinted 2002, 2004 (twice), 2005 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Second edition 2007 © 2002, 2007 Daniel Chandler The author has asserted his moral rights in relation to this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Semiotics for Beginners by Daniel Chandler

Semiotics for Beginners by Daniel Chandler Semiotics for Beginners Daniel Chandler Preface 1. Introduction 9. Codes 2. Signs 10. Modes of Address 3. Modality and Representation 11. Encoding/Decoding 4. Paradigms and Syntagms 12. Articulation 5. Syntagmatic Analysis 13. Intertextuality 6. Paradigmatic Analysis 14. Criticisms of Semiotic Analysis 7. Denotation, Connotation and Myth 15. Strengths of Semiotic Analysis 8. Rhetorical Tropes 16. D.I.Y. Semiotic Analysis Glossary; References; Suggested Reading; Index; Semiotics Links; S4B Message Board; S4B Chatroom 'Something of a classic. An absolute must for those looking for either an introduction to the topic or an inspiring and insightful reader.' - Glyn Winter, Educational and Qualitative Research Archive Semiotics for Beginners by Daniel Chandler Preface I have been asked on a number of occasions how I came to write this text, and for whom. I wrote it initially in 1994 for myself and for my students in preparation for a course I teach on Media Education for 3rd year undergraduates at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth. In my opinion, an understanding of semiotics is essential for anyone studying the mass media - or communication or cultural studies. No comparable text on the subject existed at the time so I rashly attempted to create one which suited my own purposes and those of my students. It was partly a way of advancing and clarifying my own understanding of the subject. Like many other readers my forays into semiotics had been frustrated by many of the existing books on the subject which frequently seemed almost impossible to understand. As an educationalist, I felt that the authors of such books should be thoroughly ashamed of themselves. -

Semiotics-The-Basics.Pdf

1 2 SEMIOTICS 3 4 THE BASICS 5 6 7 8222 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Following the success of the first edition, Semiotics: the Basics has 8 been revised to include new material on the development of semi- 9 otics from Saussure to contemporary socio-semiotics. This second 20 edition is fully updated with an extended index, glossary, and further 1222 reading section. Using jargon-free language and lively up-to-date 2 examples, this book demystifies this highly interdisciplinary subject 3 and addresses questions such as: 4 5 • What is a sign? 6 • Which codes do we take for granted? 7 • What is a text? 8 • How can semiotics be used in textual analysis? 9 • Who are Saussure, Peirce, Barthes and Jakobson – and why 30 are they important? 1 2 The new edition of Semiotics: the Basics provides an interesting and 3 accessible introduction to this field of study, and is a must-have for 4 anyone coming to semiotics for the first time. 5 6 Daniel Chandler is a Lecturer in the department of Theatre, Film 7222 and Television Studies at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth. ALSO AVAILABLE FROM ROUTLEDGE LANGUAGE: THE BASICS (SECOND EDITION) R. L. TRASK PSYCHOLINGUISTICS: THE KEY CONCEPTS JOHN FIELD KEY CONCEPTS IN LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS R.L. TRASK THE ROUTLEDGE COMPANION TO SEMIOTICS AND LINGUISTICS PAUL COBLEY COMMUNICATION, CULTURE AND MEDIA STUDIES: THE KEY CONCEPTS JOHN HARTLEY 1 2 SEMIOTICS 3 4 5 6 THE BASICS 7 8222 9 SECOND EDITION 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 20 1222 Daniel Chandler 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 6 7222 First published 2002 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Reprinted 2002, 2004 (twice), 2005 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Second edition 2007 © 2002, 2007 Daniel Chandler The author has asserted his moral rights in relation to this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Tove Skutnabb-Kangas'

Tove Skutnabb-Kangas Page 1 2/11/2021 Bibliography on multilingualism, multilingual and Indigenous/ tribal/minority/minoritised (ITM) education; linguistic human rights; endangered languages, their maintenance and revitalisation; linguistic genocide and crimes against humanity in education; linguistic imperialism and the subtractive spread of English; and the relationship between linguistic diversity and biodiversity. And the state of the world, and our future. Last updated in February 2021. This private bibliography (7,325 entries, 447 pages in Times Roman 12; over 1,384,500 bytes, over 184,000 words), contains most of the references I (Tove Skutnabb-Kangas) have used (or intend to use) in what I have published since 1972. There may be errors (and certainly moving to Mac did garble references in Kurdish, Greek, Russian, etc). I have hopefully deleted most of the doubles (there may still be some). If an article says “In XX (ed)” and page numbers, the book itself will be found under the editor’s name. Since I have done the latest alphabetisations automatically, everything is not always in completely right order (an example: if something with several authors has “and” or “&” between the authors, the order can be wrong). I hope my Big Bib may be useful for some people, both students and (other) colleagues. My own publications are also here in alphabetical order, but for more recent ones check my web page, www.tove-skutnabb- kangas.org, “all publications”, “publications since 2000”, and “publications in press”, which are updated more often. For (my husband) Robert Phillipson’s publications, check his webpage, www.cbs.dk/en/staff/rpibc.