Beauty's Transformation of the Ugly in Gregory of Nyssa's Life of Moses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister

Reading Guide Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister By Gregory Maguire ISBN: 9780060987527 Summary We have all heard the story of Cinderella, the beautiful child cast out to slave among the ashes. But what of her stepsisters, the homely pair exiled into ignominy by the fame of their lovely sibling? What fate befell those untouched by beauty...and what curses accompanied Cinderella's exquisite looks? Set against the rich backdrop of seventeenth-century Holland, Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister tells the story of Iris, an unlikely heroine who finds herself swept from the lowly streets of Haarlem to a strange world of wealth, artifice, and ambition. Iris's path quickly becomes intertwined with that of Clara, the mysterious and unnaturally beautiful girl destined to become her sister. Far more than a mere fairy-tale, Confessions is a novel of beauty and betrayal, illusion and understanding, reminding us that deception can be unearthed -- and love unveiled -- in the most unexpected of places. Questions for Discussion 1. While versions of the Cinderella story go back at least a thousand years, most Americans are familiar with the tale of the glass slippers, the pumpkin coach, and the fairy godmother. In what ways does Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister contain the magical echo of this tale, and in what ways does it embrace the traditions of a straight historical novel? 2. Confessions is, in part, about the difficulty and the value of seeing-seeing paintings, seeing beauty, seeing the truth. Each character in Confessions has blinkers or blinders on about one thing or another. What do the characters overlook, in themselves and in one another? 3. -

A Path to Beauty - Architects Foresee a Day When More Local Homes Fit City's Glorious Setting DOES NEW ANCHORAGE HOUSING HAVE to BE SO UGLY?

A path to beauty - Architects foresee a day when more local homes fit city's glorious setting DOES NEW ANCHORAGE HOUSING HAVE TO BE SO UGLY? Anchorage Daily News (AK) - Sunday, June 11, 2006 Author: MARK BAECHTEL Anchorage Daily News ; Staff Back in 1978, there was a civic dust-up concerning the Captain Cook statue on L Street. It seems some were offended that Cook is standing with his back to the city. At the time, Ralph Alley, an iconoclastic local architect who has since left Alaska, said there was a logical reason the good captain had turned away: Anchorage, he said, is ugly. Cook simply didn't care to look at it. While Alley took some heat for saying that, a fair percentage of those who have opinions about the look of our city -- particularly its neighborhoods -- have agreed with his sentiment. Indeed, according to a group of residential architects consulted for this article, the nearly 30 years that have elapsed since Alley spanked Anchorage for its aesthetic deficiencies haven't given Cook much reason to turn around. "Ugly means different things to different people," says architect Catherine Call. "When I think of an ugly neighborhood, I think of T1-11- siding, vinyl windows of one size repeated everywhere, a 4-in-12 roof pitch with asphalt shingles, and a two-story box." The odds are good that many reading this article at breakfast tables across the Anchorage Bowl just thought, "Hey, that describes my neighborhood." Opinions vary about what has caused the bland uniformity- that holds sway along too many of our city's streets, and there is disagreement about what might cure it or what we're really talking about when we say "ugly house." While architects and policymakers debate such questions, there is a rising tide of homeowners taking matters into their own hands. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

Ugly by Robert Hoge -223 QA

question answer page Who is the author of Ugly? Robert Hoge cover What did Robert Hoge say telling stories does for all of us? Holds us together like Krazy Glue intro What was Robert Vincent Hoge born A massive tumor in the middle of his face with? and two deformed legs. intro What was Robert Hoge's second To share his parents' story with others reason for writing his book? who may have faced similar struggles. intro What was Robert Hoge's final reason To share what it means to grow up looking for writing his book? and feeling different. intro What is the solution Robert Hogue gives to fitting all the puzzle pieces of life together? Be unafraid of living. intro What did Robert Hoge compare a newborn baby to? A lump of clay. 1 What is the date of Robert Hoge's birthday? July 21, 1972 3 What was Robert's mom's name? Mary 3 What was Robert's dad's name? Vince 3 Worked at a factory where they made What did Robert's dad do for a living? food for chickens. 3 In what city and country did Robert and his family live? Brisbane, Australia 3 How many older brothers and sisters did Robert have? four 3 At what time was Robert born? 12:35 PM 3 four toe on his right foot and two on his How many toes did Robert have? left. 3 Why did Vince Hoge know his son was a He had grown up on his parents farm, fighter and would survive? birthing plenty of calves and lambs. -

“13” Audition Monologues

“13” Audition Monologues Evan: My name is Evan Goldman. I live at 224 West 92nd street, in the heart of Manhattan, and my life just took a turn for the worst. Okay, you wanna talk about turning 13? It’s a nightmare. I’ve got hair growing in places I didn’t know were places. Plus, my parents are splitting up. Plus – plus I also have to have my Bar Mitzvah. The one event that defines you. The Jewish Super Bowl. I don’t care how much my parents hate each other. They’d better pull it together and make sure that everything about this party is absolutely, positively, for once, please God, perfect! (Answers phone) Hey mom, what’s up? What? You never said anything about moving! Where? INDIANA? Noooo! Patrice: Let me get this straight: your mom decided to move to Appleton Indiana because her cousin Pam lives here? Wow. Sounds like the divorce got ugly. So you’re going to have your Bar Mitzvah here? The one day of your life that everything is supposed to be happy and perfect. See, Catholics don’t have that day. It would go against everything we believe in. You say you’re looking for the best DJ in the best ballroom of the best hotel? That would be The Best Western. Sorry, but your choices are like my life here: limited. Come on. I’ll show you the hillside where everyone waits for the Resurrection. Brett: You two didn’t set something up? I’m very disappointed, Eddie, Malcolm. There’s gotta be a place that sets the mood right! Come on guys. -

Serpenti Forever Bag Collections

PER QUESTA PAGINA NON ESTRARRE PDF ISSUE 16 PER QUESTA PAGINA NON ESTRARRE PDF 6 Editor’s letter 8 news B.zero1 Turns 20 10 news Working Miracles 12 news Garden Architecture & Design 14 news The Mission of Art 16 around the world Made for Beauties 24 around the world Game of Flowers project Azuma Makoto 32 FIOREVER, DOLCE VITA IN ROME 34 collections Forever Diamonds photography Antonio Barrella Discover 48 the Bvlgari World collections Flowers in Rome photography Denis Boulze 74 collections B.ZERO1 ICONIC 96 collections COLOUR BLOCKS, Spring Summer 2019 98 collections Forever Serpenti photography Nicola Galli 112 news Velvet and Gold Way photography Nicola Galli 120 around the world Four Petals photography Marin Laborne, director Mario Sorrenti 126 around the world #MADEREAL Save the Children photography Rankin 130 news In Search of Wonders 132 Events photography Gianuzzi & Marino Editorial WELCOME FIOREVER AND HAPPY XX ANNIVERSARY B.ZERO1 ! The New Year begins with the launch of our new collection 4 inner petals, lent movement by the gracious trembling of the Fiorever and celebration of the XX anniversary of B.zero1, as petals and characterised by a diamond at their heart, Fiorever 20 was written XX in Roman numerals. The first stars of 2019 will become a timeless new contemporary icon for Bvlgari, will be our new Fiorever jewellery collection, presented at the together with the existing BVLGARI BVLGARI, Serpenti, end of 2018 at the Bvlgari Resort in Dubai with an incredible DIVA and B.zero1. event in the presence of its ambassador, Spanish actress Úrsula B.zero1 is already a global, unconventional, rule-breaking icon Corberó. -

Aberdeen / Matawan

■ 1 . CRPE PUB LIBRARY MATAWAN FREE 165 MAIN, ST _ B u l k R a t e m a t a w a n , - ; US Postage Paid P o t n n t n u / n IM 1 taioruuw n, p i j . P e r m i t # 6 6 BAYSHOREHUM SERVING ABERDEEN, HAZLET, KEYPORT, MATAWAN, UNION BEACH AND KEANSBURG JULY 8, 1992 25 CENTS VOL. 22 NUMBER 28 K e y p o r t m e r c h a n t s ‘ugly law’ cause split ardship? o v e r S I D Page 8 Page 3 H a z l e t Is M i l l e r A v e n u e p r o j e c t d u m p e r s Page 10 Page 11 Raring to go Bobby Bodak, 8, and his sister, Cheryl, 5, are eager to head out for a day at the beach. The u i t t m g Independent focuses on some favorite places for day trips. Pages 24-26 2 JULY 8, 1992, THE INDEPENDENT 2 2 55 2 r ! t i E E EirooD 2 ? o f 2 5 ° ° blue STAB i Beautiful Color 1 Gal. Cont. ' HARDY “THE HELPFUL GARDEN CENTERS’ for RHODOS. PERENNIALS 0 0 2 5 Hundreds to choose from Beautiful Lace Leaf PRIVET Large selection-3 gal. cont. fLAMOSCAPtbiir WEEPING 7Q99 He°GE 25 for 3 f o r ' 1 0 f o r SPREADHJGW fhuit tre f* JAPANESE ' ^ 0 0 3 f0 r3 9 » ES 19.99 each if RED MAPLE 2 ’/*’ t o 3 ’ 25 6 9 " 8.95 ea.________ 1U3 Kwazan lately teg. -

Eternal Marriage Student Manual

ETERNAL MARRIAGE STUDENT MANUAL Religion 234 and 235 ETERNAL MARRIAGE STUDENT MANUAL Preparing for an Eternal Marriage, Religion 234 Building an Eternal Marriage, Religion 235 Prepared by the Church Educational System Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah Send comments and corrections, including typographic errors, to CES Editing, 50 E. North Temple Street, Floor 8, Salt Lake City, UT 84150-2772 USA. E-mail: [email protected] © 2001, 2003 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 6/03 CONTENTS Preface Communication Using the Student Manual . viii Related Scriptures . 31 Purpose of the Manual . viii Selected Teachings . 31 Organization of the Manual . viii Family Communications, Living by Gospel Principles . viii Elder Marvin J. Ashton . 32 Abortion Listen to Learn, Elder Russell M. Nelson . 35 Selected Teachings . 1 Covenants and Ordinances Abuse Selected Teachings . 38 Selected Teachings . 3 Keeping Our Covenants . 38 Abuse Defined . 3 Our Covenant-Based Relationship with the Lord . 40 Policy toward Abuse . 3 Wayward Children Born under Causes of Abuse . 3 the Covenant . 47 Avoiding Abuse . 4 Covenant Marriage, Elder Bruce C. Hafen . 47 Healing the Tragic Scars of Abuse, Dating Standards Elder Richard G. Scott . 5 Selected Teachings . 51 Adjustments in Marriage For the Strength of Youth: Fulfilling Selected Teachings . 9 Our Duty to God, booklet . 52 Adjusting to In-Laws . 9 Debt Financial Adjustments . 9 Related Scriptures . 59 Adjusting to an Intimate Relationship . 9 Selected Teachings . 59 Related Scriptures . .10 To the Boys and to the Men, Atonement and Eternal Marriage President Gordon B. -

Downton Abbey Season 5 Casting – Jill Trevellick Cast New to Season 5 Ar

Downton Abbey Season 5 Casting – Jill Trevellick Cast new to season 5 are denoted with * CLIP 1 Season 5, Episode 1 Mr. Carson tells Mrs. Hughes that Lord Grantham wants him to accept taking charge of building the town’s war memorial. Anna and Bates share their thoughts on having a child. Thomas threatens Baxter and then discusses with Jimmy how he’s handling his problem with Lady Anstruther, his former employer. Violet extends an invitation to Lady Shackleton to join her for lunch with Lord Merton, a widower, and they discuss the issues with daughter-in laws. Baxter explains to Molesley that she believes Thomas knows something about Bates’ involvement with Green’s murder. She then asks Moseley if he has done something to his hair. Cast: Mr Carson (Jim Carter) Mrs Hughes (Phyllis Logan) Thomas (Robert James-Collier) Baxter (RaQuel Cassidy) Molesley (Kevin Doyle) Jimmy (Ed Speleers) Mr Bates (Brendan Coyle) Anna (Joanne Froggatt) Lady Shackleton (Harriet Walter)* Violet (Maggie Smith) INT. MRS HUGHES’ ROOM. DOWNTON. EVE. CARSON joins MRS HUGHES for a cup of tea. CARSON The dye is cast. I've accepted. His lordship told me to take it. MRS HUGHES There you are, then. CARSON But he was sad. Not with me. But, maybe because things are changing. MRS HUGHES Well they are. Whether we're sad about it or not. INT. SERVANT’S HALL. DAY. The SERVANTS are having tea. BATES is talking to ANNA. BATES I hope you're right about Lord Gillingham. What would I have felt if I'd inherited a family with you? ANNA You'd have loved them, I hope. -

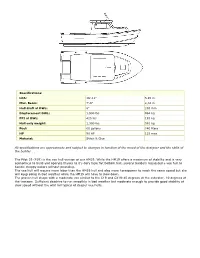

Pilot 19 (P19) Is the Vee Hull Version of Our HM19

Specifications: LOA: 18'-11" 5,85 m Max. Beam: 7'-8" 2,34 m Hull draft at DWL: 8" 203 mm Displacement DWL: 1,900 lbs 864 kg PPI at DWL: 425 lbs 193 kg Hull only weight: 1,300 lbs. 591 kg Fuel: 60 gallons 240 liters HP 90 HP 125 max Material: Stitch & Glue All specifications are approximate and subject to changes in function of the mood of the designer and the skills of the builder . The Pilot 19 (P19) is the vee hull version of our HM19. While the HM19 offers a maximum of stability and is very economical to build and operate thanks to it's dory type flat bottom hull, several builders requested a vee hull to handle choppy waters without pounding. The vee hull will require more labor than the HM19 hull and also more horsepower to reach the same speed but she will keep going in bad weather while the HM19 will have to slow down. The proven hull shape with a moderate vee similar to the C19 and CX19:45 degrees at the cutwater, 10 degrees at the transom. Sufficient deadrise to run smoothly in bad weather but moderate enough to provide good stability at slow speed without the wild roll typical of deeper vee hulls. The generous freeboard and the classic sheer are also tried and true features contributing to seaworthiness. This boat will negotiate both head and following seas with ease. The P19 will require 90 HP to cruise in the low 30 mph range. This boats transom is designed for a standard 20" shaft. -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 20 Wild Westerns: Marshals & Gunman 2 Days in the Valley (2 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 24: Redemption 2 Discs (4 Discs) 27 Dresses 4 Movies With Soul 40 Year Old Virgin, The 400 Years of the Telescope 50 Icons of Comedy 5 Action Movies 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 5 Great Movies Rated G 1917 5th Wave, The 1961 U.S. Figure Skating Championships 6 Family Movies (2 Discs) 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) A 8 Mile A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family A.R.C.H.I.E. 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Abandon 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Abduction 10,000 BC About Schmidt 102 Minutes That Changed America Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Absolute Power 11:14 Accountant, The 12 Angry Men Act of Valor 12 Years a Slave Action Films (2 Discs) 13 Ghosts of Scooby-Doo, The: The Action Pack Volume 6 complete series (2 Discs) Addams Family, The 13 Hours Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Brother, The Heritage Adventures in Babysitting 16 Blocks Adventures in Zambezia 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Dally & Spanky 2005 Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 20 Movie Star Films Adventures of Huck Finn, The Hartford Public Library DVD Title List Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. -

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Housing Demand 2025 Report

REPORT The good, the bad and the ugly Housing demand 2025 Katie Schmuecker March 2011 © ippr 2011 Institute for Public Policy Research Challenging ideas – Changing policy About ippr The Institute for Public Policy Research (ippr) is the UK’s leading progressive think tank, producing cutting-edge research and innovative policy ideas for a just, democratic and sustainable world. Since 1988, we have been at the forefront of progressive debate and policymaking in the UK. Through our independent research and analysis we define new agendas for change and provide practical solutions to challenges across the full range of public policy issues. With offices in both London and Newcastle, we ensure our outlook is as broad-based as possible, while our international work extends our partnerships and influence beyond the UK, giving us a truly world-class reputation for high-quality research. ippr, 4th Floor, 13–14 Buckingham Street, London WC2N 6DF +44 (0)20 7470 6100 • [email protected] • www.ippr.org Registered charity no. 800065 This paper was first published in March 2011. © 2011 The contents and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors only. About the author Katie Schmuecker is a senior research fellow at ippr north. Acknowledgments This report is the first paper to be published as part of ippr’s major programme of research, ‘Housing policy – a fundamental review’. We wish to thank the many individuals who have contributed to it. Katie Schmuecker at ippr north has written the report with advice and assistance from ippr colleagues Nick Pearce, Jenni Viitanen, Mark Ballinger, Andy Hull, Tony Dolphin, Sarah Mulley, Tim Finch and Dalia Ben-Galim.