African Security Review, Vol 14 No 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Shoulders of Struggle, Memoirs of a Political Insider by Dr

On the Shoulders of Struggle: Memoirs of a Political Insider On the Shoulders of Struggle: Memoirs of a Political Insider Dr. Obert M. Mpofu Dip,BComm,MPS,PhD Contents Preface vi Foreword viii Commendations xii Abbreviations xiv Introduction: Obert Mpofu and Self-Writing in Zimbabwe xvii 1. The Mind and Pilgrimage of Struggle 1 2. Childhood and Initiation into Struggle 15 3. Involvement in the Armed Struggle 21 4. A Scholar Combatant 47 5. The Logic of Being ZANU PF 55 6. Professional Career, Business Empire and Marriage 71 7. Gukurahundi: 38 Years On 83 8. Gukurahundi and Selective Amnesia 97 9. The Genealogy of the Zimbabwean Crisis 109 10. The Land Question and the Struggle for Economic Liberation 123 11. The Post-Independence Democracy Enigma 141 12. Joshua Nkomo and the Liberation Footpath 161 13. Serving under Mugabe 177 14. Power Struggles and the Military in Zimbabwe 205 15. Operation Restore Legacy the Exit of Mugabe from Power 223 List of Appendices 249 Preface Ordinarily, people live to either make history or to immortalise it. Dr Obert Moses Mpofu has achieved both dimensions. With wanton disregard for the boundaries of a “single story”, Mpofu’s submission represents a construction of the struggle for Zimbabwe with the immediacy and novelty of a participant. Added to this, Dr Mpofu’s academic approach, and the Leaders for Africa Network Readers’ (LAN) interest, the synergy was inevitable. Mpofu’s contribution, which philosophically situates Zimbabwe’s contemporary politics and socio-economic landscape, embodies LAN Readers’ dedication to knowledge generation and, by extension, scientific growth. -

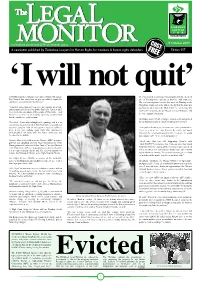

19 October 2009 Edition

19 October 2009 Edition 017 HARARE-Embattled‘I Deputy Agriculturewill Minister-Designate not quit’He was ordered to surrender his passport and title deeds of Roy Bennett has vowed not to give up politics despite his one of his properties and not to interfere with witnesses. continued ‘persecution and harassment.’ His trial was supposed to start last week on Tuesday at the Magistrate Court, only to be told on the day that the State was “I am here for as long as I can serve my country, my people applying to indict him to the High Court. The application was and my party to the best of my ability. Basically, I am here until granted the following day by Magistrate Lucy Mungwira and we achieve the aspirations of the people of Zimbabwe,” said he was committed to prison. Bennett in an interview on Saturday, quashing any likelihood that he would leave politics soon. On Friday, Justice Charles Hungwe reinstated his bail granted He added: “I have often thought of it (quitting) and it is an by the Supreme Court in March, resulting in his release. easiest thing to do, by the way. But if you have a constituency you have stood in front of and together you have suffered, “It is good to be out again, it is not a nice place (prison) to be. there is no easy walking away from that constituency. There are a lot of lice,” said Bennett. He said he had hoped So basically I am there until we return democracy and that with the transitional government in existence he would freedoms to Zimbabwe.” not continue to be ‘persecuted and harassed”. -

Final Report

Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL REPORT (2016-2018) - ANNEXES OUPUT 01: COMMUNITY-BASED DISASTER RISK REDUCTION “Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation into Local Development Planning in Zimbabwe” Project Public Disclosure Authorized A02-1.1.1a VCA / CCA ToT Report (May 2016) A02-1.1.1b Kariba Rural District Climate Change Risk Profile (June 2016) A02-1.2.1a Participatory Disaster & Climate Risk Assessment Report (2016) A02-1.2.1b VCA Refresher Training and Consolidated VCA Update Report (2017) A02-1.2.3 Community Reflection on Updated VCA Results (July 2017) A02-1.3.1 Consolidated and Updated CDRAPs and sample CDRAPs (2016 & 2017) A02-1.4.1 CDRAP & Micro-project Proposal Writing Training Report 2017 A02-1.4.3a DRR Micro-Projects 2016/17 & 2017/18 Summary Report Public Disclosure Authorized A02-1.4.3b Non-structural DRR/CCA Measures 2016/17 & 2017/18 – Health & Hygiene A02-1.4.3c Non-structural DRR/CCA Measures 2016/17 & 2017/18 – Others Public Disclosure Authorized These activities were co-financed by the EU-funded ACP-EU Natural Disaster Risk Reduction Program, managed by the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery WB/GFDRR: A02 OUTPUT 01 ANNEXES VULNERABILITY CAPACITY ASSESSMENT (VCA) TRAINER OF TRAINERS (ToT) TRAINING REPORT (Activity 1.1.1) “Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation into Local Development Planning in Zimbabwe” Project VENUE 2-days KARIBA URBAN & DATES: followed by 3-days KARIBA RURAL (Siakobvu) 22 – 28 MAY 2016 INTRODUCTION In fulfilment of outcome 2 of the project, Community Based Disaster Risk Reduction, Vulnerability Capacity Assessment (VCA) Trainer of Trainers (ToT) training was conducted in Kariba urban and rural from the 22nd - 28th May 2016. -

"Our Hands Are Tied" Erosion of the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe – Nov

“Our Hands Are Tied” Erosion of the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-404-4 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org November 2008 1-56432-404-4 “Our Hands Are Tied” Erosion of the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe I. Summary ............................................................................................................... 1 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................... 5 To the Future Government of Zimbabwe .............................................................. 5 To the Chief Justice ............................................................................................ 6 To the Office of the Attorney General .................................................................. 6 To the Commissioner General of the Zimbabwe Republic Police .......................... 6 To the Southern African Development Community and the African Union ........... -

CAP. 10:14 Names (Alteration) (Amendment Of

Statutory Instrument 167 of 2020. Names (Alteration) (Amendment of Schedule) Notice, 2020 S.I. 167 of 2020 [CAP. 10:14 Names (Alteration) (Amendment of Schedule) Notice, 2020 City/Town Old Name New Name Hellet Street Shuvai Mahofa Street IT is hereby notifi ed that the Minister of Local Government, Hughes Street Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa Public Works and National Housing has, in terms of section 4(1) of the Names (Alteration) Act [Chapter 10:14], made the following Mutare Aerodrome Road Kumbirai Kangai Road notice:— First Street Maurice Nyagumbo Street Edgar Peacock Road Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa 1. This notice may Be cited as the Names (Alteration)(Amendment Second Street Moven Mahachi Street of Schedule) Notice, 2020. Jelf Road Edgar Tekere Road 2. The Schedule to the Names (Alteration) Act [Chapter 10:14] is amended in Part VII by the repeal of certain names of roads and substitution of the following— “PART VII ROADS, SQUARES, BUILDINGS, ETC., IN URBAN AREAS City/Town Old Name New Name Bulawayo 9th Avenue Simon Muzenda Avenue 12th Avenue Joseph Msika Avenue 6th Avenue up to end of Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa 6th Avenue Extension Way 8th Avenue Liberation Legacy Avenue 3rd Avenue Nelson Kutshwekhaya (N.K.) Ndlovu Avenue 4th Avenue through to 7th John Landa Avenue Street up to King George 5th Avenue Maria Msika Avenue 1st Avenue Lazarus Nkala Avenue 10th Avenue Nikita Mangena Avenue 11th Avenue Daniel Madzimbamuto Avenue 13th Avenue to include Clement Muchachi Road Anthony Taylor Ave 14th Avenue George Nyandoro Avenue Connaught Avenue Cephas Cele Avenue Cecil Avenue continuing Albert Nxele Way up to Wellington Road Fife Street and Queens Queen Lozikeyi Street Supplement to the Zimbabwean Government Gazette dated the 17th July, 2020. -

01-14-2019 19:25___Executive Summary__The Gnassingbé Clan Has Ruled the Country Since 1967. the Demand

Munich Personal RePEc Archive BTI -2022 Togo Country Report : political and socio-economic development, 2019-2020 [enhanced author’s version] Kohnert, Dirk Institute of African Affairs, GIGA-Hamburg 28 December 2020 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/107022/ MPRA Paper No. 107022, posted 10 Apr 2021 04:25 UTC Author’s extended and annotated version of BTI 2022 – Togo Country Report’, forthcoming Togo’s Political and Socio-Economic Development (2019 – 2021) Dirk Kohnert 1 Source: “No, to 50 years more”, Africa Youth Movement statement on protest in Togo #TogoDebout/ iDA Abstract: The Gnassingbé clan has ruled the country since 1967. The demand for political alternance, constituted the major contentious issue between the government and the challengers of the Gnassingbé regime throughout the survey period. The first local elections since more than 30 years took finally place on 30 June 2019 and resulted in the victory of the ruling party. Shortly afterwards, in February 2020, the President won also the disputed presidential elections and thus consolidated his power, assisted by the loyal army and security services. The outbreak of the Corona epidemic in Togo in April 2020 and the subsequent economic recession may have contributed to limit popular protest against the Gnassingbé regime. The human rights record of the government has improved but remains poor. Despite undeniable improvements to the framework and appearance of the regime's key institutions during the review period, democracy remains far from complete. However, the international community, notably Togo’s African peers, the AU and ECOWAS, followed a ‘laissez-faire’ approach in the interests of regional stability and their national interests in dealing with Togo. -

The Mortal Remains: Succession and the Zanu Pf Body Politic

THE MORTAL REMAINS: SUCCESSION AND THE ZANU PF BODY POLITIC Report produced for the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum by the Research and Advocacy Unit [RAU] 14th July, 2014 1 CONTENTS Page No. Foreword 3 Succession and the Constitution 5 The New Constitution 5 The genealogy of the provisions 6 The presently effective law 7 Problems with the provisions 8 The ZANU PF Party Constitution 10 The Structure of ZANU PF 10 Elected Bodies 10 Administrative and Coordinating Bodies 13 Consultative For a 16 ZANU PF Succession Process in Practice 23 The Fault Lines 23 The Military Factor 24 Early Manoeuvring 25 The Tsholotsho Saga 26 The Dissolution of the DCCs 29 The Power of the Politburo 29 The Powers of the President 30 The Congress of 2009 32 The Provincial Executive Committee Elections of 2013 34 Conclusions 45 Annexures Annexure A: Provincial Co-ordinating Committee 47 Annexure B : History of the ZANU PF Presidium 51 2 Foreword* The somewhat provocative title of this report conceals an extremely serious issue with Zimbabwean politics. The theme of succession, both of the State Presidency and the leadership of ZANU PF, increasingly bedevils all matters relating to the political stability of Zimbabwe and any form of transition to democracy. The constitutional issues related to the death (or infirmity) of the President have been dealt with in several reports by the Research and Advocacy Unit (RAU). If ZANU PF is to select the nominee to replace Robert Mugabe, as the state constitution presently requires, several problems need to be considered. The ZANU PF nominee ought to be selected in terms of the ZANU PF constitution. -

Togo: Thorny Transition and Misguided Aid at the Roots of Economic Misery

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Togo: Thorny transition and misguided aid at the roots of economic misery Kohnert, Dirk GIGA - Institute of African Affairs, Hamburg 8 October 2007 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/9060/ MPRA Paper No. 9060, posted 13 Jun 2008 10:14 UTC GIGA Research Programme: Transformation in the Process of Globalisation Togo: Failed transition and misguided aid at the roots of economic misery1 Dirk Kohnert October 2007 Abstract The holding of early parliamentary elections in Togo on October 14, 2007, most likely the first free and fair Togolese elections since decades, are considered internationally as a litmus test of despotic African regimes’ propensity to change towards democratization and economic prosperity. Western donors took Togo as model to test their approach of political conditionality of aid, which had been emphasised as corner stone of the joint EU-Africa strategy. Recent empirical findings on the linkage between democratization and economic performance are challenged in this paper. It is open to question, whether Togo’s expected economic consolidation and growth will be due to democratization of its institutions or to the improved external environment, notably the growing competition between global players for African natural resources. Key words: democratization, governance, economic growth, development, LDCs, Africa JEL Code: F35 - Foreign Aid; F51 - International Conflicts; Negotiations; Sanctions; F59 - International Relations and International Political Economy; O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements; O55 – Africa; P47 - Performance and Prospects; P48 - Political Economy; Legal Institutions; Property Rights; Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology Dr. Dirk Kohnert is economist and Deputy Director of the Institute of African Affairs (IAA) at GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies in Hamburg, Germany, and editor of the scholarly journal ‘Afrika Spectrum’ since 1991. -

Election Watch | Zimbabwe January 2012

Election Watch | Zimbabwe January 2012 MEASURING THE ZIMBABWEAN ELECTORAL ENVIRONMENT ACCORDING TO THE SADC GUIDELINES GOVERNING DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS On the 17th of August 2004, the Southern African Development Commu- nity (SADC) leaders adopted the “SADC Principles and Guidelines Governing Democratic Elections.” As a member of SADC, Zimbabwe was a signatory to these benchmark principles, and therefore it is entirely fitting that Zimbabwe’s performance in relation to the future elections be measured against these principles and guidelines. The Electoral Institute for the Sustainability of Democracy in Africa presents a brief overview of Zimbabwe’s electoral system on their website. SADC principles for conducting democratic elections: Divergence/Obstructive Legislation Compliant 2.1.1 Full participa- • War veterans stormed the location at Vumba Mountains o Yes tion of citizens in where the Zimbabwe Constitution Select Committee S No the political process (COPAC) technical team has retreated for the drafting of the final document, demanding a halt in the constitu- tional drafting process • Citizenship of Zimbabwe Amendment Act, 2003 • Guardianship of Minors Act, 1961 • Broadcasting Services Act, 2001 www.idasa.org 2.1.2 Freedom of • Police defied a court order and disrupted an MDC-T rally o Yes association at Komayanga business centre in Nkayi, Matebeleland S No North • Public Order and Security Act, 2002, amended 2007 2.1.3 Political • A crackdown on Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai’s o Yes tolerance supporters has S No followed the bombing -

National Youth Service Training

National youth service training - “ shaping youths in a truly Zimbabwean manner” [COVER PICTURE] An overview of youth militia training and activities in Zimbabwe, October 2000 – August 2003 THE SOLIDARITY PEACE TRUST 5 September, 2003 Produced by: The Solidarity Peace Trust, Zimbabwe and South Africa Endorsed nationally by: Crisis in Zimbabwe Coalition Zimbabwe National Pastors Conference Ecumenical Support Services Harare Ecumenical Working Group Christians Together for Justice and Peace Endorsed internationally by: Physicians for Human Rights, Denmark The Solidarity Peace Trust has a Board consisting of church leaders of Southern Africa and is dedicated to promoting the rights of victims of human rights abuses in Zimbabwe. The Trust was founded in 2003. The Chairperson is Catholic Archbishop Pius Ncube of Bulawayo, and the Vice Chairperson is Anglican Bishop Rubin Phillip of Kwazulu Natal. email: selvanc@venturenet,co.za or [email protected] phone: + 27 (0) 83 556 1726 2 “Those who seek unity must not be our enemies. No, we say no to them, they must first repent…. They must first be together with us, speak the same language with us, act like us, walk alike and dream alike.” President Robert Mugabe [Heroes’ Day, 11 August 2003: referring to the MDC and the possibility of dialogue between MDC and ZANU-PF] 1 “…the mistake that the ruling party made was to allow colleges and universities to be turned into anti-Government mentality factories.” Sikhumbuzo Ndiweni [ZANU-PF Information and Publicity Secretary for Bulawayo]2 “[National service is] shaping youths in a truly Zimbabwean manner” Vice President Joseph Msika [July 2002, speech at graduation of 1,063 militia in Mt Darwin]3 1 The Herald, Harare, 12 August 2003. -

MDC – Harare – Bulawayo – Council Elections 2006 – Gukurahundi

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: ZWE31570 Country: Zimbabwe Date: 20 April 2007 Keywords: Zimbabwe – MDC – Harare – Bulawayo – Council Elections 2006 – Gukurahundi This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Does the MDC have an office in Harare? 2. How many branches are there in the province of Bulawayo? 3. How many wards are there? 4. Can you provide information on the leaders of the MDC in the province of Bulawayo? 5. Can you provide information on the activities of the MDC in the province of Bulawayo in 2006? 6. Can you provide information on council elections in Bulawayo around October 2006? 7. Did Zanu PF lose seats in the council elections in Bulawayo in October 2006? 8. Can you provide information about Gukurahunde? RESPONSE 1. Does the MDC have an office in Harare? The MDC headquarters are located in Harvest House, the corner of Angwa Street and Nelson Mandela Avenue in Harare. Angwa Street is parallel to First Street. Attached is a map of Harare, showing Angwa Street, First Street and Nelson Mandela Avenue (Africa South of the Sahara 2003 2003, Europa Publications, 32nd edition, London, p.1190 – Attachment 1; Mawarire, Matseliso 2007, ‘Police left a trail of destruction at Harvest House’, Zimdaily.com website, 29 March http://zimdaily.com/news/117/ARTICLE/1480/2007-03-29.html – Accessed 30 March 2007 – Attachment 2; ‘Harare’ 1998, Hotels-Tours-Safaris.com website http://www.hotels-tours-safaris.com/zimbabwe/harare/images/citymap.gif – Accessed 30 March 2007 – Attachment 3). -

Zimbabwe's Operation Murambatsvina

ZIMBABWE'S OPERATION MURAMBATSVINA: THE TIPPING POINT? Africa Report N°97 -- 17 August 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION: OPERATION MURAMBATSVINA.......................................... 1 A. WHAT HAPPENED .................................................................................................................1 B. WHY IT HAPPENED ...............................................................................................................3 1. The official rationale..................................................................................................3 2. Other explanations .....................................................................................................4 C. WHO WAS RESPONSIBLE?.....................................................................................................5 II. INTERNAL RESPONSE ............................................................................................... 7 A. THE GOVERNMENT: OPERATION GARIKAI ............................................................................7 B. ZANU-PF ............................................................................................................................8 C. THE MDC.............................................................................................................................9 D. A THIRD WAY?...................................................................................................................11